Quoting Baudelaire, an American passes in Granada.

Usually things go badly when I am mistaken for an Arab. Usually, but not always. Once my friend Wanda and I took a trip to Granada to hear flamenco and found ourselves in a noisy cave drinking at a table with two Moroccans. “Salaam aleikum!” they shouted. “Wa-aleikum-as-salam!” I shouted back.

Usually things go badly when I am mistaken for an Arab. Usually, but not always. Once my friend Wanda and I took a trip to Granada to hear flamenco and found ourselves in a noisy cave drinking at a table with two Moroccans. “Salaam aleikum!” they shouted. “Wa-aleikum-as-salam!” I shouted back.

“Adil,” I asked the better-looking man in Spanish (Puerto Rican pidgin, not Castilian), “do you know the work of Baudelaire or his concept of the flâneur?” In bodegas and on subway platforms back home, I am often mistaken for a Puerto Rican. And though I sometimes enjoy that mistake for the chance it affords me to be a spy, I propped my spinning head in my hand, glad for the ocean between me and New York, glad for the rolling rasgueado of the guitar and the chattering of the bailador’s castanets.

I thought Adil might be familiar with Baudelaire on account of Morocco having been colonized by the French. But he wasn’t. “I’m just a working man,” he shrugged, showing me his hands. They were big as bear paws and nicked with scars. “I don’t know anything about art or philosophy.”

“Fair enough,” I said. “It’s just that right now while the air is full of smoke, and the bartender is shouting at the waitress who has dropped that tray of beer glasses, and the Alhambra is floating above our heads like something out of a fairy tale, and the gypsies are making my heart hurt with this song, and you are passing me a portion of your chocolate hashish. I find myself soaking these things up like a rag.”

In bodegas and on subway platforms back home, I am often mistaken for a Puerto Rican. I sometimes enjoy that mistake for the chance it affords me to be a spy.

“Oh, that,” he said. “You do not need a fancy word for that. That’s just life. That’s just what you are supposed to do. For example, I have a boat. When the sun comes up, you will sail home with me to Tangier. We will arrive in time for lunch. My mama will cook a tagine.”

“With apricots?” I asked.

“If you like,” said Adil. “Will you come?”

What would Baudelaire do? “Of course,” I said.

Wanda had loaned me an English translation of Baudelaire, which was why I was thinking about him at the time. There was plenty of time to read at the artists’ colony, a former olive mill at the foot of a lion-colored mountain in Andalusia where I met Wanda. Time, time, endless time.

I liked Wanda instantly because she wrote a poem every morning, inspired by the dreams she’d had the night before. (“But what if you don’t remember your dreams?” I’d asked her. “I always remember my dreams,” she’d said.) She called these poems “wake-up calls” and one of them was about a Wonderbra, which is what I had taken to calling her.

Wanda was in Spain because it was the landscape of Lorca, and I was there because I generally feel more at home away from home—Brazilian in Brazil, Mexican in Mexico, Dominican in the Dominican Republic—in places where I blend in. This is harder for me in black nations, like Jamaica, and in Sugar Hill, Harlem, where I live; an irony since I, like Wanda, identify as black. So there we were, Wonderbra and I, two African-American girls in a gypsy cave in the South of Spain. Except I barely looked black and the Moroccans refused to believe she was American.

I generally feel more at home away from home—Brazilian in Brazil, Mexican in Mexico, Dominican in the Dominican Republic—in places where I blend in.

There is no English equivalent for the gourmet term, flâneur, which is one of the reasons I love it. Baudelaire defined it as “a gentleman stroller of the streets.” And since the word comes from the French verb flâner, loosely translated, flâneur designates one who strolls, a drifter, a wanderer, a saunterer. But none of those words capture the double stance of detachment and attunement the flâneur takes when he roves a city. Baudelaire saw the writer as a flâneur, an alienated, isolated, melancholic, anonymous dandy. Part sociologist, part anthropologist, part historian, part artist, the flâneur’s role is to observe the life of the city, but also to participate in it. With the exception of a fudge brown coat lined in purple silk I once splurged half my rent on at Hugo Boss, I don’t have an elegant enough wardrobe to call myself a dandy. Still, this stance, simultaneously part of and apart from, is how I have always felt in relationship to my blackness and to my country.

“Tell him I’m American,” insisted Wanda, who did not speak Spanish or Arabic. “Tell him I’ve been American for four hundred years!”

Omar, the less good looking of the pair, wanted to know where in Africa she came from. He thought Wanda a snob for denying her roots. Of course she was doing no such thing. She would have praised God if she could point to the exact place on the map that bore her ancestors, but she could not.

I sat there swimmily witnessing Wanda’s double consciousness on display like a headdress: “an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Though more than one-hundred years have passed since W.E.B. DuBois, a mulatto, wrote The Souls of Black Folk, I cannot think of a more articulate description of black psychology. Wanda cannot be both African and American any more than I can be both black and white.

“I’m American, don’t you get it?” Wanda sputtered, growing more frustrated with Omar and Adil, who were indeed looking at her with amused contempt and pity. I wasn’t making the same claim for myself, though I’m often forced to do so back home when people ask me where I’m from. For the moment, I didn’t want to spoil the rare and beautiful feeling of blending in, of being an insider, of belonging.

This stance, simultaneously part of and apart from, is how I have always felt in relationship to my blackness and to my country.

“I understand that she lives in America,” Omar argued, “same as us living in Spain. But we don’t pretend we’re Spanish! We are African and so is she. Tell her she is African, like us.”

“Wake up, Wonderbra,” I teased, partly enjoying Wanda’s exasperation. “You are African, like us.” When we first met, she hadn’t believed I was black any more than these two believed she was American. I couldn’t exactly blame her. My skin is the color of a wooden spoon.

“Quit passing!” she cried. “Tell him we’re American! Tell him about the Atlantic slave trade! Doesn’t he know about that?”

“I can’t,” I said, not knowing how to translate the way we were trapped in the nightmare of history, and perhaps not wanting to. I wanted to sail away and eat an apricot tagine. “I don’t know how to speak in the past tense.”

Emily Raboteau is the author of The Professor’s Daughter: A Novel and the recent recipient of a grant from the NEA. She is at work on a book of travel writing about black Zionism.

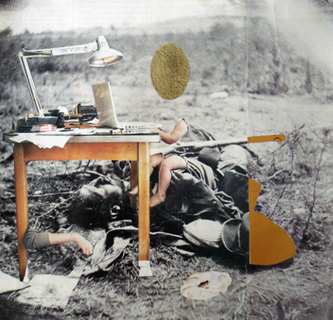

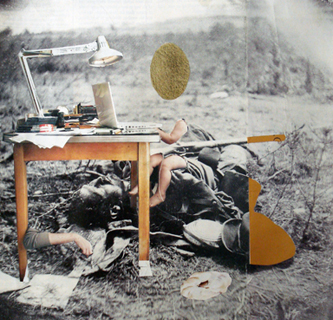

Art by Emily Hunt