The girl who lived at the end of the street had been gone from school three days, and I couldn’t decide if I should go knock on her door, or if I should just wait and see. The last time she missed school like this, her mother had poured a hot pan of frying plantains on her. The girl had returned to school, left arm exposed, with bright pink wounds on her dark skin like inkblots. No one really said anything, not even the teachers. Up to that point, we had known that something was not right at her house, but not bad enough that we couldn’t joke on her about it. She was a year up from me, so I didn’t see her often in the halls, but the few times I did go past her in the cafeteria, I just smiled in her direction and tried not to see her arm.

I decided to wait.

Even in the ghostly morning fog, the neighborhood felt safe. All the houses looked alike. Still, there was a weird and constant feeling of being watched through closed blinds, a paranoia that was especially alive on our street. I looked, but the girl was nowhere. I listened for the bus through the vibrant buzz of cicadas, raised my face upward, and imagined I could see atoms floating, a lightheaded feeling I believed could explain to me the way things fit together.

We were not the only Nigerians in the area, but we were among the first. I had been in America for four years and before that had lived nine years in Nigeria with my mother. She never received her visa, and it was for that reason that, by thirteen, I was no longer a regular at church. I lived with Grace and other times with Gramma, guided, it seemed, by nothing more than the moon and Grace’s whims.

When they first told me that I would be going to America to live with Grace, the first thing on my mind was this: How will I get along with her husband? I didn’t ask my mother about it because my father had died young, and I didn’t believe that she knew much about husbands. I asked instead about Grace.

Grace is my sister, she said. Ofu nne, iche nna. The same mother, different father. But she is still my sister, and she is good.

When? I asked. How long? Why? But the answer to that last question is as evident as the sky above.

I promise to join you soon, my mother said. But until then, Grace will train you, and America will give you everything else. Are you listening?

I listened, but I lacked faith in the unknown, an anxiety that would go on to grip me. But just then, it was an unconscious confusion, like an unsatisfying feast, because all throughout I thought only of the cost. At what price did America come?

Will she beat me? I asked.

Listen, my mother said, always remember that it is not an easy thing to train another woman’s child. But it is our culture, and it is the only way for you to get a proper education, which is my first and last concern.

I had seen the girls who received training from hands that were not their mothers’. My mother called it training, but as far as I had seen, it looked more like servitude. Some of them had been well cared for, but far too many had left the pot of poverty only to land in the fire. They were house girls, unseen and unrecognized, endemic in the Nigerian consciousness, necessary as the seasons, as un-regarded as corruption taking the streets. These girls, daughters of no mothers, work for their keep in the houses of relatives if they are lucky, or they are sucked up by insatiable homes if they are cursed. House girls, black as coal, engines of society. Ghosts everyone sees but no one says a thing about.

It was a fate from which I was largely spared. I came to America and found that I didn’t have to worry about Grace’s husband. She had divorced him some time back. He had been violent when drunk. That was part of the quarrel between Gramma and Grace. I picked up what I could from their rows and learned that Gramma had sided with Grace’s husband, had accused Grace of not only inventing the abuse but of also provoking the man. He was, to Gramma, a saint, and she pushed Grace to stay in the marriage. Grace, twentysomething with a master’s degree and possibilities in her eyes, stayed until she quit for good when he started beating on her while she was pregnant the second time. The first child had lasted five months in the belly but was lost, a fate I did not believe a person could endure twice without losing their mind. I lost the plot after that—an incident that Grace sometimes alluded to and Gramma seemed to know of very well, though she would deny all knowledge if asked. Whoever was right or wrong, I was just glad Grace had left the drunk, because I had never lived with a man before and was not ready to start learning how.

At school, I took the tardy to look for the girl. She was nowhere. Yet she obsessed my thoughts. She seemed oddly American, but I was not sure she was born here. Her mother, Queen, was certainly an immigrant, but her older brothers and younger sister looked like they were born in America. You can always tell born-at-home Nigerians from the ones born elsewhere, akatas, especially the Nigerians who come to America and riff off black hip-hop culture while actively forgetting the native one. Still, others argue that akatas are all blacks not born in Africa. True, it is only semantics, but if we cannot agree, then how can we define ourselves?

The girl seemed to have acquired the akata sensibility, but it was in an undigested way, so she seemed always to present a mockery of the akata appropriation of black American culture. Her misinterpretation was just like Gramma’s over-zealous piety, a similarly undigested version of Christianity that turned to madness when met by her traditional ways.

I couldn’t tell you why I obsessed over the girl the way I did. She looked like me somehow, in the way you can sometimes recognize yourself in the gangly posture of a tree. Maybe I kept an eye out for her because I didn’t really believe that anyone else would. Not that there was much I could do but to bear witness and someday tell her story.

Maybe that’s why I always noticed her, kept a tab of her appearance—a visible record of how things were with her. I didn’t assume she was very bright. You know how you can just look at a person and tell if they use their brain or not? With the way people treated this girl and the way she was always painting herself a target, you would not be blamed to call her simple.

She was always in disagreements with everyone from the principal to the lunch ladies. I don’t know who gave her the most grief, the akatas or the white kids. Take, for instance, the afternoon she got into an epic word battle with Oladi. This was long before the burn. It happened after school by the bus ramps, and a crowd eagerly gathered around Oladi and the girl. Everyone was there. The yellow buses in the sun looked like a row of Twinkies waiting to be filled.

Oladi was a quick-mouthed akata boy, the coldest assassin of verbal beat-downs and the girl’s frequent and most-hated nemesis. All that day, Oladi had clowned the girl about her outfit. She wore what in Nigeria we call an up-and-down, matching shirt and pants. Except hers was a 1980s two-sizes-too-small polyester getup with black and white diagonal stripes that looked like a flash of lightning when she did her quick-walk. Unfortunately for Oladi, the girl keyed in on his chipped front tooth, an injury he was especially sore about because of the way it had happened the week before in gym class. In slow motion, the girl mimed Oladi grinning idiotically and running blindfolded smack into the brick wall at the other end of the gym. When that elicited a huge roll of laughter from the crowd, the girl mimicked Oladi’s dumb shock as he picked up his broken tooth. To finish, the girl stuck out her teeth and covered the front tooth with her finger, pretending it was chipped.

Uh, Coach, she mimicked. She forced air through her teeth and perfectly dramatized the slow, panicked realization that came over Oladi’s face. Coach… uh, I think something happened.

That had been the best part, Oladi’s incomprehension, even with the evidence of the broken tooth in his hand. We doubled over in laughter. Oladi was stunned. Our whoops drew the attention of several teachers. Knowing she had won, the girl gripped the good strap on her bag, rolled her head, and pushed her hand in Oladi’s face—a brilliant double blow because a hand to the face means you’re dismissed to an American, but to a Nigerian, it means fuck you, your mother, and your father. Oladi was slain. But as the girl turned to quick-walk away, the sight of her buttocks twisting agonizingly in the lightning pants was, as some swore, the funniest thing any of us had ever seen.

After an unsuccessful day of searching for the girl, I skipped the bus and walked home instead. That one chance decision would lead to my irrevocable embroilment with the girl, something far more involved than abstract fascination. The sun had been baking the ground all day, and the bayou that I walked along—which was really just a swampy ditch—gave off moist heat. There was an egret I always looked for when I walked there. Ann Wan had showed it to me. Ann lived next door to Grace, and I was sometimes friendly with her. It was on the afternoon that she, Ann, told me about the quarrel between her and her father. Ann and her mother had found out about his other family back in his home country. He was an older man, and it had been a long time since he left his country and wife. And his children. Mrs. Wan, a kind woman, chose to pretend that the other family did not exist and went on living as though nothing had changed. But Ann confronted her father, angry at his abandonment, afraid, I knew, of what that meant for her. When she asked him how and why, he simply said that he no longer existed there. Everything was severed.

I didn’t question Ann about it, but I understood that he had become something more and something less than her father. After four years, my mother had become as foreign as Nigeria to me, and it was rare that I wanted to claim either. As for my father, I had long ago mythologized him, bound by worship. And I did not think much about Grace, who in turn treated me like a nonentity, but every now and then, she felt the need to lay down the law.

Ann showed me the egret that she said was her own and told me what she had named it. I looked at the bird a long time—it had no distinguishing markers—and wondered how anyone could claim to own something that was so naturally free.

Now, as I looked for the egret with no way of knowing if I found it, I was reminded of something I had heard Grace say about the girl’s mother, Queen.

The woman is wicked, Grace had said. Damn wicked.

Grace was upset with Queen for stealing her clients. Grace had been among the first wave of Nigerians to take advantage of the real estate business in Houston. She had worked hard to create a strong demand among Nigerians for her trusted services and was not about to let an upstart like Queen encroach on her ground. But sometimes when I overheard Grace talking, it sounded like the market was declining and business was not going like it used to. She blamed it on the fact that too many Nigerians had heard it was good money, and now every Nigerian was a mortgage broker or real estate agent.

It is in our nature, Grace had said. Our people are schemers by birth.

I knew all about schemes. It was a scheme that brought me to America. My mother, desperate and driven only by the thought of my education, had heard stories of Nigerians who made it to the States and became naturalized citizens. They then came back and took their sister’s daughter, or some other child in the family, to give them a life in the States. They would adopt the child in America, and in a year or two, the kid would be newly minted with papers, stamped and approved. But the scheme was flawed, and all too often, the child was stranded in America without papers and unwilling to go home. Getting to America was the dream of everyone I knew. And if not, then it was to get their children there. I remember thinking in Nigeria that people probably thought of nothing else. I know that I certainly did not. America was on my mind like a drug.

My mother had tried several times to secure our papers. We would travel countless hours by bus and arrive at the gates of the immigration building when the streets were thick with night. We slept across the street from Immigration’s barbed-wire gate and armed guards. I remember, on one of our attempts, my mother pulling a flattened cardboard box from the gutter and laying several wrappers over it. She sat, then laid me down and rested my head in her lap to sleep. Just before morning broke, she woke me up and braided my hair, washed my face with her spit, and put me in the blue dress—always the blue dress—and shined the shoes on my feet. My mother was a seamstress, so I had many dresses, but the shoes were for special occasions. My mother went behind a wall to ease herself, and I sat on the wrapper, watched the other immigration campers wake. They were whole families sprawled on bare and filthy ground. Hausa men prayed in the direction of Mecca, a pregnant woman breastfed her baby, and the guards across the street stretched and shouldered their guns.

I remember very clearly the last time my mother and I went to Immigration. Every detail had been painstakingly accounted for, meticulously prepared by my mother. All of the documents had been procured, forged when necessary, and signed by all of the appropriate state authorities. Money had changed hands to assure the speedy processing of said papers. My mother was supremely confident in our chances, but as the line started forming at the gate, she took my hand and held it firmly as though afraid someone would snatch me away from her. She jostled us to the front of the pack, and we were among the first when the window of a small office near the gate opened. At the window my mother pulled out papers when they were asked for and answered yessir and nosir.

I had never known my mother to answer sir to anyone. The man behind the counter was fair-skinned and gaunt, unkempt, more like a boy than a man. I couldn’t understand why he addressed my mother as though she was not his senior. He did not look up once, and when he pricked his finger on the needle my mother had used to attach my passport photograph to the form, he became irate and tore the application, screaming about us lousy Nigerians as if he wasn’t one himself.

My mother and I never made it through the gates of Immigration. The next time I went, it was with Grace. I was enamored of her: caramel-colored and beautiful, her speech lightly dusted with British English. The grounds of Immigration were covered with green grass trimmed short. It was the first time I had ever seen grass that was manicured or not dying or littered with trash. When my visa was stamped, I held Grace’s hand and swung our arms happily. I knew something great had just happened, the significance of which I did not fully understand.

There you have it, Grace said. My sister can never say that I did nothing for her.

I gave thanks to Grace, and on the other side of the gate, my mother cried and held me while the people standing in line looked at us a long time.

An egret squawked in the bayou then took flight, and I was returned from my memory. I walked to the clubhouse restrooms where I sometimes found half-smoked cigarettes and, once, a nearly full pack. I circled the squat building with little luck, but as I turned the last corner, I found the girl leaned casually against the wall. She was so suddenly there that I nearly believed my obsessive thoughts had materialized her. I tried to conceive the worst possible reasons she could have been gone.

Seeing me, she stamped her feet and jerked her shoulders as though shaking off the annoyance of my presence. It was a gesture so familiar and Nigerian that I remembered myself and smiled. She wore a red bandana tied around her head, a faded orange shirt that looked designed for a younger girl, a plain black skirt. I went to her.

You were gone, I said too intimately.

Dodging, she said without so much as a glance at me.

How is your sister, I asked.

Fine.

What of your brothers?

Fine, she snapped.

Your mother? I tried.

She jerked her shoulders and looked about wildly. She had these intense eyes, large and protuberant. They were a constant source of torment for her at school: you couldn’t lose her in the dark! Had I known any more of her relatives, I would have asked after them, too. But, I held back, not wanting to seem like I was prying. Had we been in Nigeria, I would have probably felt better about asking after all of her people.

Hel-lo, she said and shifted her weight impatiently. May you be excused please?

What are you doing here? I said, but meant, Where have you been?

Did you hear me? May you be excused please? As in bye.

Just wait, I said, wondering why I had even gone looking for her in the first place. She was unbroken, and I had not anticipated her hostility.

I’m waiting, she said, and tapped her feet.

Look, how are things at your house?

Does it concern you?

I shrugged. It doesn’t, I guess, I said.

Then it’s not your cause, she said. She kissed her teeth loudly and impressively.

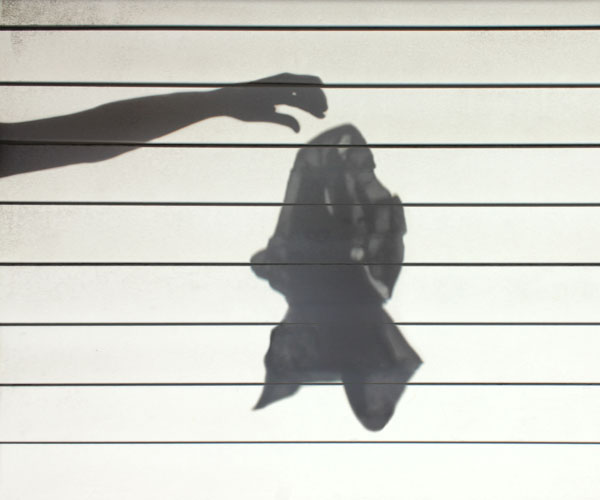

I felt that I had seen and known her then. She had the neck-rolling, constantly bored attitude down right, and the quickness of her speech hid most of the accent, but the very language she used was Nigerian through and through. I felt grand. I had desperately needed for her to be born in Nigeria, and I could admit it to myself now that it was true. It was the pleasure of finding things out that opened me up, unmasked me, and made me see her arm. It wasn’t wholly disfigured but was as disheartening as an abandoned lot. I looked and looked until I thought that I could never not look, until all that was left was the marred length of her arm, the lightly puckered scars, the hairless patches, the skin that healed several shades lighter. I saw myself deep in the wound. Unable to reason or articulate the order or chaos that caused it to be her disfigured arm and not my own, I saw myself in the scar and suffered a deep animal want to save myself, to claw open the arm and pull the child out of the wound.

I found a decent cigarette butt on the ground. I fumbled a lone match out of my pocket and dragged it against the brick wall. I pulled deeply and welcomed the ravaging of my lungs.

It’s okay, you know, I said, aware of how I was sounding.

What d’you know? she said, pointing her nose at me.

She was right. What did I know? Where were my scars?

I don’t know, just thought you might understand, I said, and passed her the butt. She pulled without inhaling, coughed, and passed it back.

What is it doing you to know?

Nothing, I said.

Ah-beg, just leave me alone to be managing my life.

You call that managing? I pointed at her arm.

Yes-I-do, she said while dramatically misapplying finger snaps. Why you laughing? she asked.

Deciding against explaining it to her, I said, You’re funny is all.

She blinked.

Lis-ten, I got plans, she said. Big, big plans. You wait and see. I’ll be a star.

A star? Where? Doing what?

What do you mean doing what? Singing, of course. In Hollywood.

I was stunned. She liked to sing. Up till that moment, I’d never imagined that she had desires beyond tomorrow, certainly nothing so outlandish as stardom.

Anyway, my auntie lives there. My real one, not by stupid marriage. She raised her arm to show me and spoke with real disdain in her voice.

Oh, I said.

I finally understood. Queen was not her mother as we had all been led to believe. She was the girl’s aunt, and not even by blood. Queen’s husband, dead of a heart attack, was the girl’s biological uncle, and had probably been the girl’s only defense against Queen.

The girl tilted her head as if registering me for the first time, a flash of judgment, then a decision. She slowly slid the bandana off her head and mussed the newly hacked hair with her hand.

Got caught in my mumsi’s makeup drawer, she said with a slight grimace.

What did she use?

Kitchen knife. Idle hands are the work of the devil, right?

Yeah, Grace always says that, too. It’s so annoying, I said. Grace was convinced that I stole.

Your mumsi?

I hesitated. Not exactly, I said.

I see.

Silence found its way between us once more, but now it was of a different texture.

Anyway, that’s how come I’m sitting here waiting at this dump. Been suspended cause of my bandana, and I’m dead at home, so.

Nowhere was safe. Again, understanding overwhelmed me.

You can still wear your hair to school, I said. It’s not that bad, I added.

She blinked.

So Oladi and them can disrespect me? You must be dumb, she said, and rolled her neck.

What will you do?

Ask me if I know. Anyway, I’m going.

She shouldered her bag and quick-walked away in the direction of her sister’s school. Slowly, the facts realigned themselves: the little sister was in fact her cousin, as were, undoubtedly, her brothers. I returned to the path, looking occasionally to the ditch, its angular slope and moss-covered run, the trickle of water at the middle steaming.

I knew that I had to help the girl. The school had a strict no-headwear policy and the principal didn’t play any games. The girl couldn’t serve out her suspension at home because it would have surely resulted in a beating. The red bandana was ratty at best, and to our humorless principal, it was probably reminiscent of gang affiliation. But perhaps the girl could get away with covering her head if the scarf was expensive and pretty, inoffensive.

I wasn’t allowed to enter Grace’s room when she was not at home, so I had to make haste. When I got to the house, it was empty. I took the stairs in twos and threes. At Grace’s door, I froze, listened. I was half convinced that I would open the door only to find her on the other side, waiting for me. I inched the door open a little, then a little more. I listened.

Grace’s aggressively flowery perfume and the massive four-poster bed dominated her room. In the shuttered evening light, I maneuvered to the en-suite bathroom. Grace’s closet was the one place I was banned from ever entering. Yet, I found my way there often, although I never could quite enjoy just being there for fear of getting caught. It was an anxious desire that was exactly my appetite.

I knew Grace’s closet intimately. I knew that she kept a shoebox full of quarters and gold dollars on the top shelf. I knew that there were over thirty pairs of shoes lining the shelves. I had seen the various places she hid the letters my mother had sent from Nigeria. She had stopped giving them to me after a year or two, and I was too scared to break their seal or steal them. I had stopped caring about the letters as I learned to forget, and perhaps even hate, my mother.

Grace didn’t manage her closet like a tyrant, but she was quick, and sometimes knew if something was missing. Since she was always accusing, and I was always denying, and it seemed to be no one’s fault, she invented a trouble-making imp named Ima, and she blamed him for the little disappearances from her closet. She would call on lightning to strike Ima dead wherever he stood, and she did so with such electricity that I would step aside just in case she really could command lightning.

I found the flower-printed scarf I was looking for, one that I knew Grace wouldn’t miss very quickly or badly, if at all. The air in the closet cool and clean, I inhaled deeply one last time, listened, then quickly stepped through the room, and guided the door shut behind me.

The next morning, I left the house early to intercept the girl as she dropped her sister-cousin off at school. I ran into them near a small park, and we walked with our heads down, minding the ground because it was another foggy morning. The sister-cousin complained and yawned with a pampered sweetness that I found sickly. We waited for her to enter her school before we went on.

When we reached the sports-club restroom, near the bayou, I pulled the scarf out of my right sleeve, held it in front of the girl, and hoped that she would understand what to do with it. She took it without words and sheepishly wrapped it around her hand. She dropped her falling-apart bag dangerously close to a shimmering anthill. She struggled with the scarf and tied it in different styles. I didn’t know how to advise her since my own hair was always in a braid and rarely adorned. I stared instead at the fire ants and gently kicked her bag away from the pile.

Hurry up, I said finally.

Hurry up yourself, she shot back.

She tied a simple knot at her nape, swung the loose ends over her shoulders like two long ponytails, and we hustled to school. She seemed grateful. Her step livened, and I remembered what about her was so charming. She had energy, simple and unimpeded, unlike me, always tired and thinking. When we reached the school, she was herself again with her wide mouth ready to talk back. She took off quick-walking, and it was as though we did not know each other at all because, in fact, we did not.

All that day, I remained in a low humming state of agitation with my ears scanning the frequencies of school gossip for any news regarding the girl. By lunchtime, I’d heard nothing. She seemed to be lying low. Yet, my worries went unabated. I could handle the school authorities if they should ever question. The fear, always, was the mother. Eventually my thoughts drifted to the mother-aunt, Queen, who by all accounts was an unsmiling, uninviting woman. Her husband had died before the burn. Heart attack on the living room floor. The sons, big boys, had been arguing over a five-dollar bill, and with their teenage gym bodies, the argument was on the verge of fists. The father, home in the afternoon with a migraine, emerged to stop the squabble and had put himself between his sons. He shouted the boys down until his heart popped. Dead over five dollars. It had all seemed so absurd.

Some weeks after the burial, the girl showed up to school with fat welts on her arms and legs. That day, I skipped lunch and found her changing in the last shower stall of the girl’s locker room. I crouched down, peeked under the curtain. The welts covered her back in fat ridges as though her body was rejecting her skin. She pulled her gym shirt on carefully, stretching the fabric wide so it did not scrape her skin. Her legs were incredibly skinny and firm. The back of her panties were stained dark rust, and thickly folded toilet paper stuck out on either side of her panties. I left the locker room, sick. Later, I overheard some akatas laughing about an extension cord and that jungle justice.

A few days went by without any noise about the scarf or the girl. But just as I was beginning to believe that things had resumed a natural hush, I was called to the principal’s office. It was on a Friday, and as I roamed the emptying halls, deliberately confounding my route, delaying the inevitable, there was no question in my mind what had happened. The girl’s flagrant behavior had brought unwanted attention upon her. Try to help her and this is how she repays me.

Inside the office suite, the secretary pointed me to the back with her pen. There, I found the girl on her knees. Her head was bare, and Queen stood behind her. The principal was leaned forward on his desk and looked harassed.

Do you know this scarf? the principal asked, and held up Grace’s scarf.

No, I said.

I was transfixed by Queen. Her skin was fair with hints of dark spots, the telltale sign of bleaching creams. I wasn’t surprised she bleached her skin. Many Nigerians in the States and back home do. Queen leveled her eyes at me, and they were like magma.

Look, she doesn’t need to kneel, said the principal, but without force.

This is how we punish bad children, said Queen.

The principal threw his hands up in the air and returned his attention to me.

Headwear is against school dress code, he said. You knowingly supplied one to a student. You know the rules. I have no recourse but to issue the prescribed full-week suspension, in-school, of course. We must notify your mother.

My mother is in Nigeria, I said, though I knew well what he meant.

Your legal guardian, then.

Queen kissed her teeth loudly, for the principal as much as for me.

Are we through? she asked, and without waiting for a response, she exited with the girl in tow, pulled along by the ear.

The scarf on the desk reeked mercilessly of Grace.

Grace didn’t come home that night, and I decided that whichever Grace would come would come. Grace with the short fuse and surprising laugh. I slept with the light on.

Saturday mornings were usually for perfunctory duties and pleasant mindlessness. Grace owned a magnificent stereo that, when she had guests, filled the house with the king of pop and the voice of Africa. I dusted it. In the living room there was a big-screen TV built into custom cabinets, above which hung an impressive framed photograph of her father. I wiped the shelves down.

At some point, Grace’s skinny, freckled legs appeared in front of me, and the scarf dangled by her knee. I knew that if I looked up, Grace would not be wearing any clothes. I don’t know why she distrusted clothes the way she did, but in the house, her body was always exposed or barely covered with a wrapper. I took the temperature of her mood and found it smoldering.

Just what is this? she demanded.

She was testing me to see if I would lie. She was convinced that I was a liar.

I don’t know, I said.

What do you mean you don’t know?

It was a question that merited no response since she knew that she had me cornered, and I could say nothing to level with her.

I didn’t do anything wrong, I insisted. And in a sense, it was the truth. But Grace had other ideas, and just like that, she ignited.

Get up. Get up, nwa nka! Better confess and shame the devil.

She pulled me up by the scruff of my famous Rockets t-shirt. It was a commemorative ’94 championship tee, heavy and ill-fitting, but it was a pride worn regularly. Up to that moment, Grace had never laid a hand on me. She claimed it was a great kindness on her part.

You know what? I blame myself, she said. I am too easy on you.

I protested: It’s not my fault. What was I supposed to do? She beats her!

You are supposed to do what I tell you and nothing else, Grace said. I have told you time and again, if you don’t listen, you will feel.

But, that woman, I began, but couldn’t bring myself to speak Queen’s name, thereby exalting her.

Shut your mouth, nwa nka, Grace said. Who asked you to speak? There’s nothing about that woman you can tell me that I don’t already know. It’s none of your business. Don’t go putting your nose where it doesn’t belong. And don’t make me tell you again, I don’t want to see your fingers on my things. She kissed her teeth. And if you know what’s good for you, just stay out of my sight. I can’t stand to look at you just now. In fact, close your eyes the next time you see me coming.

So, she had known about the girl all along. I wasn’t surprised. Everyone talked, yet everything managed to remain secret. What surprised me was Grace asking me to keep my mouth shut about Queen. This ability to see and swallow the truth astounded me. I thought of all the women who had seen and swallowed this very truth. And this was my invitation to feast. It was my first taste of the secrets that interlocked to form our community, at once vibrant and silent. The girl was just one casualty. I wondered where the others were hiding. What were their stories?

She starves her just for burning the rice, I exclaimed.

It is our culture! That’s the way we were brought up. This is nothing new. Please don’t question me, nwa nka, said Grace.

Her exposed breasts jerked violently.

Grace often called me nwa nka, this child, as though to make me forget that my mother had named me Ifeoma, something fine. My mother who was still in Nigeria and forgetting about me, who time could not cure in my heart. Grace was correct. I was only one child. But how many more go without voice? It may be our culture, but it’s one thing in Nigeria where at least we can talk freely and not among strangers. America has a way of twisting us into something else altogether, indeed at times very ugly.

So, a man can use his pregnant wife as a punching bag, but that’s okay, ’cause it’s our culture, right? I said this while looking directly into Grace’s eyes because I wanted her to hear me.

I knew it was a deep cut. The look on my face just then must have been like a mirror, because she coiled back like a startled snake, instinctively raised her hand, and delivered a furious strike against my cheek.

I did not drop my head. I would never expose my neck to her like that. Instead, I stared at her naked body. Her breasts were small cupfuls. Her nipples bristled, and the mound between her legs was smothered with hair. Her body was a road map to all of the things I could expect to have in my life.

Her face brewed anger in one moment, utter confusion in another, then pleading. She looked like she didn’t know me at all. Then just like that, her face turned, and I felt that she approved. I don’t know if she approved of my attempt to help the girl or if she approved the meeting of her hand and my face. In that way, knowing Grace was like walking on slowly sinking ground.

Are we through? I asked, trying out the line.

She gave a slicing look of warning, kissed her teeth, and retreated to her bedroom, presumably to lick her wounds. I could see her through the open door. She stood by the bed and beat the pillows into a suitable shape. She balanced herself on the bed and grabbed the remote control off the bedside table. She punched the buttons, scanning the channels. She chewed her bottom lip furiously. Something on the TV made her laugh, and it sounded like a bark.

Out in the backyard, the pepper bushes that thrived when Gramma was around were now shrubs in the sun. Gramma had a gift for greens, and in those first American months, her garden was, to me, greater than all of the Niger Delta.

The sun swelled. There was no breeze, no relief to speak of. I thought of the girl and wondered if she had survived the night in Queen’s house. America is a hard country, I was learning, especially for the children of other countries. I wondered how any of us would survive without our mothers to lay us in their laps and let us sleep.

The afternoon unwound yet somehow managed to get stuck. The same stuck feeling of African afternoons, when the sun blows and everything stops or slows, a dense spiritual quietness that turned to restlessness as I increasingly kept American time. I tucked a book into my shorts and ran out through the half-raised garage door. Mrs. Wan was standing in the middle of her lawn, her hose poised as water pummeled the dying grass. She waved a greeting, and I returned the hello.

I went once again in search of the girl. When I reached her house, I stood across the street and scanned the windows for any signs of life. I weighed the odds of ringing the doorbell only to have the door opened by Queen. It was not lost on me that it would be the girl’s neck and not mine, but I had to know for sure. I knocked and the door was opened, not by Queen but by one of the boys. Perhaps he recognized me, but he certainly didn’t care. He waited impatiently for me to declare myself. Instead, I saw beyond him to the girl. She stood frozen on the stairs, pled my secrecy with her eyes. I discretely mimed the international gesture for smoking a cigarette, and when she nodded, I took off running without any regard to the boy.

When I reached the clubhouse bathroom, I searched for butts, but the grounds had been recently swept clean. I waited, and when the sun’s beam became unbearable, I went into the ladies’ room, lined a toilet seat with paper, and sat. I hoped that she had understood my message and that she was industrious enough to make herself disappear from the house, even just for a few moments. Every now and then, the spent fluorescent light sputtered and blinked rapidly.

Finally, I heard the sound of someone calling, the familiar hiss of a snake.

Sssssss, it came again.

I’m inside, I called, knowing the girl had come.

She was wearing the lightning pants and church shoes. Her bag, now strapless, was stuffed with clothes, and she propped it against the foot of the sink. I eyed the bag. Nearby, a puddle of water she had failed to notice.

I’m going, she said. Hollywood.

Today? I said dumbly.

Yes, today-today, now-now. She snapped her fingers in my face.

I visually checked her body for harm. I wasn’t sure that I wanted to know what had transpired at her house to finally make her say enough was enough.

How? Do you even know how to get there?

Greyhound. I have cash, she said conspiratorially, stone-cold cash.

Cold and hard, you mean, I said.

She blinked.

I didn’t want to know how the money came into her hands, the same way she didn’t ask me about the scarf. I couldn’t understand her plan. Like everything else about her, it was haphazard and doomed. I let her know it was crazy.

No, it is you who is crazy if you think I’m just gonna stay here waiting to die.

Had it truly come to this, I wondered, life or death?

Lis-ten, she said, I just need a little more cash for a cab. I have to get to the bus station, pronto.

Don’t ask me for another single thing, I said.

It would be hard enough getting a taxi at all; we might as well have been living in the boonies. I was ready to list for her all of the things that could go wrong. She could be found out by Queen, or she could be picked up by police, or ruined in a truck stop somewhere. But I was halted when something visibly broke in her. She spread her arms and displayed herself in evidence.

Where else I’m gonna go?

Her eyes were large and begging.

How are you going to call a cab? With what phone? Don’t you think?

Please, she said.

I knew then that I would continue to lash myself to her wild and messy existence. Of course I would help her. I had known it when I knocked on her door, had known it the moment I heard her whimper as she gingerly pulled her gym shirt over her razed back. It seemed that all my days had been driving to this very moment, and I was bereft of choice.

I can’t let you do this, I said.

Let me? she snapped. Since when are you my mother and my father? She kissed her teeth.

She was resolute. I attempted a final appeal to reason.

We can think of something else, I said.

I looked around the dingy restroom as if for inspiration, and came up short. We decided she would wait for me.

I left her sitting on the toilet seat where moments ago I had sat and counted tiles to make time pass. I ran all the way home. As I crawled through the garage door, I heard the backyard door slide open, followed by Grace’s voice. I couldn’t make sense of her conversation, but by the pitch of her voice, I knew that she was calling Africa on a bad signal. I snuck up the stairs and left my ears stationed at the back door.

Grace’s handbag was not in her room as I’d hoped. I searched the closet and came up with the shoebox full of coins. I stuffed the box into an old Neiman shoe bag and left the room undisturbed. I stole down the stairs. My heart clattered helplessly. I traced Grace’s voice to just outside the back door, perhaps with one leg already poised to enter. I would have to dart right under her radar. I saw it all. The front door was safer but farther away. Plus the door would beep when it opened. The garage door, on the other hand, was closer and hadn’t been closed properly, but it would be in direct sight of Grace if she happened to turn around. Without thinking, I dashed through the garage door, a move so fluid it was as though I elevated an inch or two above ground. I felt in my element. I ducked across the lawn and could not help but notice how guilty I must have looked to anyone who might be watching.

Intuitively, I ran to Ann Wan’s house. In the past, her mother had been unusually kind to me—she called me in from the rain when Grace had locked me out of the house; she took me to school with Ann when I missed the bus; she fed me even when I told her I was not hungry—and it was perhaps for this reason that I ran to her home when there was nowhere left to go. I knocked on the door breathlessly, and Ann opened it on my third try.

She looked, as always, slightly alarmed. I had not thought of what story to tell, and before I could spin something believable, Mrs. Wan appeared behind her daughter and opened the door wider.

I need to use your phone, I blurted.

It was so honest that Mrs. Wan did not immediately question me. Instead, she looked at me with eyes that seemed to mind me, concerned and watchful in the way that my mother had often looked at me. I sometimes wrongly thought I saw my mother’s eyes everywhere. But here they were, unmistakably, and I almost wanted to drop the shoe bag and beg for absolution.

Come, come, Mrs. Wan said.

Mother and daughter waited patiently while I used the kitchen phone with my back to them. The Neiman bag was tucked under my armpit, even as I thumbed the phonebook. I called a taxi service, and my voice dropped when I gave the school address. Finally, I had confirmation; the taxi would arrive in twenty minutes, but not even that assurance could cajole me to relax a little.

All is well?

I turned and faced Mrs. Wan and felt instantly that she could see right through me.

Yes, I lied. Yes, yes, fine, thank you. I continued to thank her profusely even as I bolted and left the front door crashing behind me.

It had all been movement: my escape from Grace, the mad uneven sidewalk dash, the sun dropping over the voodoo bayou, arriving breathless at the clubhouse restroom and startling the girl. Is someone chasing you? she asked.

Leave it, leave it, I screamed and grabbed her arm when she went back for the hairbrush that had fallen from her bag. I saw the ancient quality of her long, powerful legs striking the path. Her feline speed and my haggard breathing. I cursed myself to keep up, keep up, at the very least don’t lose sight of her. We were propelled by fear. I had a vision of the taxi arriving early and pulling away from the empty school lot just as we arrived. But when we reached the school, we exhaled deeply when we realized that we had not only made it but had done so with enough time to look each other in the eye and laugh in the face of impossibility.

The girl speedily repacked her bag while I counted the gold dollars and quarters into separate socks, which I then knotted at the top. Shortly, the taxi appeared, turned into the school, and crawled up the semicircle drive. It came to a stop in front of us, and the back door of the cab miraculously popped open. Without words, the girl tossed her bag into the cab and allowed herself entrance into its dark breast. We clasped hands, but she was already letting go, even as she squeezed.

The driver seemed to have hardly noticed us and only took his cue to drive when the door slammed shut. The cab followed the curved drive to its end, winked at the intersection, tucked a right, and was gone.

Only then did I think to copy down the plate number, just in case. I slumped to the ground and sat, depleted. A deflated lung. The concrete on my skin was like a warm stone I welcomed. I pulled my knees up to my chest and thought I would stay a while to watch the sun fade, spent and wasted, sure that when they found me, I would still be in the same position. The girl’s name was Mimi, a sweet name I envied.