“Meaning what?” said Celia.

She and Bart stood nearest to the roped-off exhibit, a flat box the size of a kitchen TV. Letters moved across its wide black field, plunging and flipping over, like synchronized swimmers.

Wait, I’ll die and be right there.

Bart shrugged. He was considered the smartest kid in their class and questions were always addressed to him. By default, so to speak. Though currently Bart was the one defaulting. He didn’t want to look foolish in front of Celia, but what could he say to her if his mind was drawing a total blank? TV shows didn’t cover anything of this sort. Frustrated, Bart looked up: the portrait of Gregory House hung in its usual place, on the wall by the window. House was smiling, the kindly wrinkles fanning out around his eyes like the folds on Klelia’s gloves. His beard was forked like a snake’s tongue. His face held no surprises.

Klelia clapped her hands. Then she remembered she was wearing gloves, took them off, and clapped again. “Listen up, kids!”

Celia shifted closer to Bart.

“Congratulations,” Klelia began, mysteriously, and Bart felt like rolling his eyes. Now she’d start harping on about how lucky they were, what an extraordinary place this Museum was, how only the very best were ever admitted—as if they themselves didn’t know they were fortunate. Celia didn’t take her eyes off Klelia, and Bart, unnoticed, used his tongue to probe a small pimple in the corner of his mouth. Disgusting! Couldn’t it have waited till later? No, it had to turn up today of all days.

Celia stood so close to him. Her hair was like flowing honey; it smelled of flowers. Meanwhile, Klelia kept bumbling on.

“Yes, kiddos, you are the very best. You’ve proven yourselves with your superior grades and hard work, and now you deserve a glimpse into the dark world of the past, the world that will be revealed to you today by our guide. Please welcome—Dexter DuBois!”

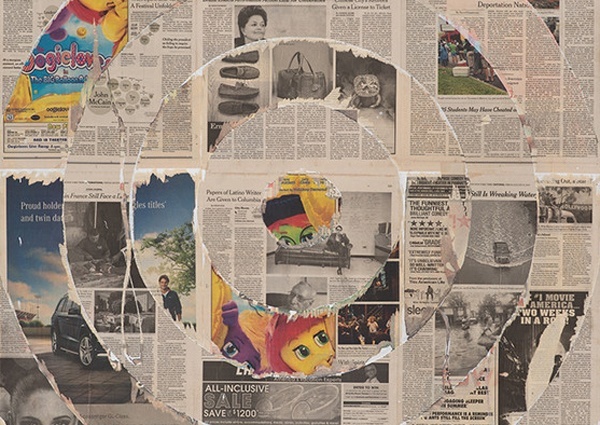

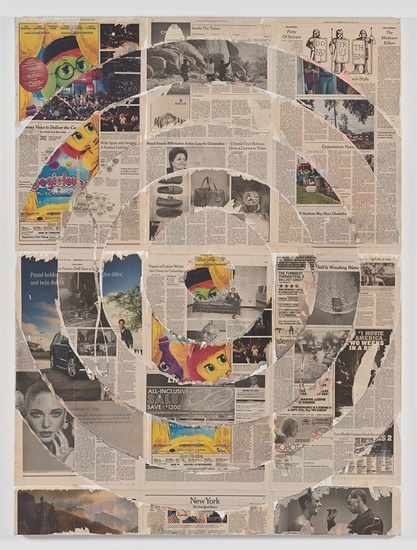

The lights went off and Celia grabbed Bart’s hand, her fingers smooth like chess pieces. In the dark, three-dimensional letters floated by, forming words: “BAN INTERNET—THIS IS NORTH KOREA. ALEXEI IVANOV.”

“I don’t understand,” Celia whispered, her warm lips tickling his ear. “Who is Internet? What is Korea? And what sort of name is Alexei Ivanov? Is it even a person’s name or is it a thing?”

Bart remained silent. He didn’t understand anything either, but he’d never admit it. Not in front of Celia.

The letters grew bigger and bigger; the giant “A” from the name—or whatever it was—“Alexei” rose up to Bart’s nose and popped like a soap bubble.

Then music began to play. “Souvenir De Trianon” by W. Müller—Bart immediately recognized it. All the letters were popping now, as if someone were shooting them down. And finally that someone emerged—Dexter DuBois! First they saw a pale, splayed palm; then cheeks and black mutton chops; then eyes with tears pasted over the epicanthic folds. According to Bart’s sister, Hightower, it was the latest word in fashion. She herself had had three surgeries to get these exact epicanthic folds, and every month she had to glue on new tears. Hightower was a fashionista. Too bad she’d done so poorly in school and would remain a nurse for the rest of her life.

“She’s awesome,” Celia whispered.

“He’s awesome,” Dexter DuBois corrected her, coyly. “I’m a man. I’m just disguising myself a little. Welcome to the Museum, the place where the terrors of the past come to life. You all must be bursting with questions!”

The lights came on, and Bart and Celia grimaced as if they’d just shared a lemon. My god, what was he thinking! He couldn’t eat in Celia’s presence; he was constantly pretending he had no appetite and later felt like dying of hunger.

In the light, Dexter DuBois turned out to be a coquettish pervert of an uncertain age. Between fifty and seventy, Bart decided. But no more than seventy—his skin was just too smooth, not a liver spot on his hands.

“My lovely Klelia!” Dexter bent over the teacher’s hand and pecked the air with his painted lips. You could tell he found her repulsive. Klelia, the idiot, didn’t notice; she was smiling like they did two centuries ago, when everyone walked around smiling all the time. Freaky! These days only the total country bumpkins bared their teeth in this way. Fortunately Klelia remembered that she was not just in the City, but at the Museum—the place of holy terror. She wiped away her stupid grin, thank God.

Hightower never got to tour the Museum. This was a once-in-a-lifetime chance for a person: if you didn’t get to go at sixteen, you never would. Though to be fair, there were some exceptions—teachers and Guardians like Dexter.

“I have a question. Have you worked here long?”

“What a quick boy.” Dexter seemed surprised. He pulled a loupe on a chain from his pocket. Through the lens, his nearsighted eye with its pasted-on tears looked like a peephole from the detective show they’d been assigned to watch for Psychology homework the other day. Bart broke down at Episode 8, fell asleep right in front of the TV, and in the morning his mother scolded him for being lazy. Him, the best pupil at the school!

Having seen enough of Bart, Dexter put the loupe back in his pocket.

Dexter paused, giving them a chance to understand just how great he looked for his age.

“Guardians stay at the Museum from their youth until their death. Once upon a time I was just like you, Bart Cartman, arriving here for the first time. And now look at me: one hundred and three years old and still here!”

Dexter paused, giving them a chance to understand just how great he looked for his age, but their group was clearly not receptive. Only kind Celia politely raised her eyebrows.

“That’s right,” Dexter continued, sounding hurt. “I am still here, and I know almost everything about the old world. It’s possible that I know even more than its citizens, who all succumbed to the deadly condition called the Internet.”

“Was it contagious?” asked Celia.

“Of course, Celia Cooper. It’s not an accident that this disease was known as the Worldwide Web, or simply the Net. The infection was transmitted by these seemingly innocent little boxes—computers. Those who purchased a computer immediately were part of a high-risk group. But to become infected they still had to connect to the Internet.”

“Why did they do it?” asked a timid boy who kept close to Klelia.

“Because, Sheldon Smith, no one had warned them how dangerous it was. Fortunately, you all live in Russia, a free country, where everyone knows that it’s risky to even approach one of these machines.”

Dexter snapped his fingers and music began to play, forceful yet tender. “Little Morning Wanderer” by Schumann.

Bart knew very little about computers. In the old TV shows they watched in History, computers were obscured by gray blurry squares, like the ones on the paintings with nude body parts. Nudity was another terrible relic of the past, just like the network epidemic that had destroyed the whole world. Only Russia had survived, thanks to Gregory House and his wise decision to burn the Internet off like a wart. Not surprisingly he assumed the name of the greatest healer in history.

“That’s one small step for a man,” House added in his historical speech, “but one giant leap for mankind.”

Perky Dexter marched ahead of the group; Klelia was bringing up the rear, as if they were not at the Museum but on a particularly dangerous hike through the woods.

The guide stopped next to a midsize display stand and waited for the others to catch up. Sheldon, who was nearsighted, tried moving closer, immediately tripping the alarm.

Dexter snapped his fingers again; the nasty beeping stopped and piano music came on again—Schumann’s “Chiarina.” Bart’s dad had loved this piece; he’d passed away last year. Bart felt he might start crying any minute—such bad timing. Luckily “Chiarina” was a short piece and would soon be over.

On the display were four portraits. Bart would guess these people had lived at the end of the twentieth century, judging by their clothes, awkward smiles, and the quality of the photos. “Sir Timothy John Berners-Lee” appeared somewhat embarrassed; “Bill Gates,” guilty; but Bart found that he rather liked “Steve Jobs.” The fourth man was named “Gabe Newell,” and from the looks of him, he’d long been denying himself any quality nutrition or exercise. For the children of the twenty-second century this was difficult to imagine.

Dexter described in detail all the evils these four had done, getting the world addicted to their harmful inventions and so-called “gadgets.” He told them about the Internet, Steam, Apple, and Microsoft, which were the other names of Satan. To Bart it all seemed vaguely familiar, as if he’d already heard these names before. But, of course, he was also frightened, and as for Celia, she clung to him and shivered as if from cold.

“Don’t worry, they won’t come to life.” Bart did all he could to calm her, but when Dexter heard him he burst out laughing.

“Won’t come to life! Ha-ha. I like you, Bart Cartman. Your name, I assume, was inspired by The Simpsons and South Park, correct?”

Bart bristled. He didn’t like being treated like this, not in front of Celia.

“You know other shows that feature Barts?”

“There’s a Burt Hummel in Glee,” said a girl from another school. A top student like Bart, she had five stripes on her shoulder. Klelia proudly lifted her chin. Just look at our children!

“Excellent, Maria Waldorf,” said Dexter. “Now let’s move on to the next exhibit and I’ll show you how people communicated at the beginning of the twenty-first century. They’d almost lost the ability to speak, but each was connected to a special device. It could be a computer—stationary or mobile. Or it could even be a phone—like this, take a look!”

Dexter carefully held a black object the size of a TV remote. Except a remote only had two buttons, while this object had many. It looked nothing like the cozy, plush phone with a tail that could be found in every Russian home.

“This is a phone?” Maria sounded astonished.

Dexter pressed a button and they all heard brief signals that undoubtedly were telephone beeps. Bart felt something like envy toward their guide, who could so casually handle such contraptions.

“People didn’t just communicate by way of phone calls, like we do with the help of our trusty fluffy phones. They sent so-called text messages, often nonsensical and even insulting. A so-called emoticon had to be added at the end.”

A raging sea of small yellow circles with eyes, feet, ears, and even horns glowed on the screen. They were expressing feelings and actions, sometimes quite obscene. Bart was ashamed to admit that he also liked these little weirdos.

“At the start of the twenty-first century, people sent each other text messages and pictures. That was how it started—the great tragedy of the century, the death of the Russian language. Fortunately, the English language saved our ancestors in the nick of time and they managed to survive, unlike the rest of the world, where no one speaks anymore. The problem, my lovely children, was that along with the text messages, the world was facing a much more terrifying threat.

“Social networks! Porn sites! Computer games! Virtual travel! Kitten pics! Chat rooms! E-books! Downloaded music! Facebook!”

“The Internet?” squeaked frightened Celia.

Dexter closed his eyes in a tragic manner. “Yes, Celia, the Internet. Although, like Satan, it came in many guises.”

The guide stormed ahead of the group as if possessed, switching on one screen after another.

“Social networks! Porn sites! Computer games! Virtual travel! Kitten pics! Chat rooms! E-books! Downloaded music! Facebook!”

“I don’t understand a word he’s saying,” whispered Celia.

Bart was also confused, to put it mildly. He had expected something else from this tour: his father, for instance, had reminisced about his Museum visit up until his death. How sorry Bart was that Dad didn’t live to see this day. Especially since Hightower missed her chance and would never find out what was hidden behind these gray walls. Bart, in any case, wouldn’t be the one to tell her. As for Mom… Mom was so scared of everything, it was best not to discuss with her such mysteries as Facebook and GChat.

“Every day people chronicled their lives in virtual diaries and posted images of themselves. And their acquaintances—who they might have never met in real life—added “likes” under these images.

“From the verb to like?” asked clever Maria, and Dexter touched his fingers to his tears, as if he were crying from happiness.

“Precisely, dear Maria! Precisely! Our poor ancestors didn’t suspect the immensity of the abyss opening before them. While they “liked” pictures of kittens, the life around them was becoming more and more dangerous. There were no more children being born. Nations annihilated one another. The planet was dying; animals and plants were becoming extinct. The air itself had turned noxious. But the virtual folk didn’t care—they each had a network baby and some had several. Not to mention 3-D zoos and strategy games.”

Klelia, Bart noticed, had been biting her glove for some time now. Such a nervous woman. As for the guide, he was still regaling them with horror stories of the olden days.

“Our hapless predecessors didn’t believe it was possible to live without the Internet. In one of his books, author Alexei Ivanov compared the Internet ban to North Korea—it’s written in the now-dead Russian language and unfortunately even our very clever Bart Cartman won’t be able to read it. There was once this ideal country, North Korea, with a very intelligent government, but the virtual people thought it was an unhappy place. Because it didn’t have the Internet.

“And that was when Gregory House arrived.”

Dexter clapped his hands and an enormous mural lit up under the domed ceiling. It pictured a man with a forked beard and a giant CD over his head, his arms spread, as if he were trying to protect Bart, Celia, Maria, Sheldon, Klelia, and Dexter from the horrors of the past. Obviously, the horrors had stayed in the past, but the image still brought hot tears of gratitude to Bart’s eyes.

As if reading his mind, Celia said, “We’re so lucky to be living in Russia.”

This part of history Bart already knew well, from the TV shows they had watched last year. Gregory House led an uprising, destroyed harmful computers, mobile phones, and gaming devices—and then destroyed their owners. He installed some trusted people to guard the borders and started building a new state. Without the Internet and high technology. Without cell phones or any digital devices.

“It wasn’t easy.” Dexter Dubois mournfully lowered his head. “Our dear House had enemies who wanted to stop him. They tried to attack our country with nuclear bombs and bio weapons, but still we prevailed! We won! Our people were saved by their faith in the truth, brought to us by our TV screens.”

Obedience was in the blood of every Russian citizen.

After that, the lecture got really boring, but the students listened anyway. Obedience was in the blood of every Russian citizen.

“Our babies see their first TV shows while still in their mothers’ wombs. Every year they gain more and more knowledge, and once they grow up they join the TV-series Factory, where everyone finds his own calling. Of course, some have to combine this work with other duties, like raising children or making food. But our life’s work continues to be the creation of television serials. Our people are even named after popular TV heroes, and may it always be this way.”

“Can I ask a question?” said Bart, feeling braver. “Why should we remember? Why bring the best students to the Museum?”

Dexter came so close he almost set off an alarm inside Bart. Up close the guide’s face looked fatigued, diminished by time.

“Why? That’s a great question, Bart Cartman. I was right about you.”

He clapped his hands again, and the Gregory House mural was at once consumed by darkness.

“Every month our security forces capture new inventors who are trying to build yet another computer. Every day—you’d be surprised, children—fools attempt to abandon our wonderful country for the dying world across the Border, the world that is quite literally living out its final days.”

Celia flinched. Once, when she was little, she and her dad were walking in the woods and accidentally came upon the Border. She didn’t like to recall how quickly her strong grownup daddy fled from that place.

“We want to show you what the old world was like—cold, indifferent, and scary. And you—our best students, our hope and pride, our future screenwriters, directors, and actors—you will be saved just in time. We won’t allow our country to descend into the terrifying abyss of virtual death.”

Dexter was shaking his head so vigorously it looked like it might roll off his shoulders.

“Of course, we won’t allow it!” Klelia joined in. Her voice had grown a bit raspy in the time she’d been silent, and the children were startled, not recognizing their teacher at first. “Let us thank our dear guide for his engaging story. If anyone has any other questions, he’ll be happy to answer them.”

The group was silent.

“Well, I have a question for the young Bart Cartman,” said Dexter. Celia suddenly reached for Bart’s hand and he felt her icy fingers shaking. “Would you be so kind as to join our director for a cup of carrot tea? Don’t wait up, my dear ones. Farewell!”

Celia frowned and opened her mouth as if to speak, but Klelia prodded her toward the exit. She was wearing her gloves again.

“I forgot to ask,” Celia called out toward Dexter’s retreating back. “What’s Wait, I’ll die and be right there?”

The guide spun around on his stiletto heels.

“That’s how children talked at the beginning of the twenty-first century, when their mothers called them to dinner, for example. These poorly behaved children played shooting games on their computers. The hero of the game could die multiple times. He had many lives, but according to the rules, the hero had to either win or die before the game could be started over. The child would “die” and then come to dinner. And his mother wasn’t at all alarmed.”

Celia grew pale.

“Bart, I’ll be waiting for you outside.”

“Don’t waste your time, Celia,” said the guide, and Bart saw that he was even older than he’d said. At least one hundred and twenty.

The door closed behind the guests, and Dexter led Bart to the stairs.

“We have chosen you, Bart Cartman, to be a Museum Guardian,” Dexter said ceremoniously. “Congratulations!”

“What about the director?” Bart said, stupidly. Chuckling, the guide reached into his pocket and retrieved a mobile phone. Just like the one in the Museum exhibits, except this one was real. A yellow envelope was pulsing on its screen.

“The Director is waiting!” said Dexter. He grabbed the boy’s arm and pulled him up the stairs toward the closed door. Behind the door there were voices and a loud, steady noise, like that of a far-away city.

Bart was afraid to open the door, afraid to see his nightmare come true, the one that had been haunting him since his father’s death. Dad died at night; next to him were tangled black cables and two lifeless TVs. Bart was very afraid, but Dexter had disappeared. All around him was darkness, and under the door was a yellow strip of electric lights. Celia would cry for a bit and then forget him. Mom had Hightower. Hightower had her beautiful epicanthic folds. And Bart—he had his faith in television and in Gregory House. He’d make it somehow—he was the best in school after all.

Bart narrowed his eyes and pushed open the door.