The first time I read Yambo Ouologuem’s novel, Bound to Violence, I was shocked by the fury and seeming lack of restraint with which he wrote the story. Yet at the same time, his inventive style struck a chord with me, although I could not immediately explain why. I discovered the novel by chance at an antiquarian bookshop in Eindhoven, where I was living after my arrival in the Netherlands as a refugee fleeing the First Gulf War in Kuwait. The novel was tucked among books that had nothing to do with Africa, lined up alphabetically in a row as could be expected in bookstores or libraries. It was at that antiquarian bookshop that I encountered this book written by a man with a name that sounded Nigerian at first. The cover of the English translation was eye-catching: it was black with an image of a carved wooden mask impaled by a spear. The subtitle was noteworthy and revealing: A savage, panoramic novel of Black Africa.

I had previously thought that I knew the majority of novels by writers from Africa. I had grown up with, among others, Heinemann’s African Writers Series, which began with the publication of the seminal Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, who became the first editor of the series. I had read Heinemann masterpieces including works by Sembene Ousmane and Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and the only novel by Cheik Hamidou Kane, Ambiguous Adventure (1961), one of my all-time favorites. But I had never heard of this particular writer. Who was Yambo Ouologuem? Despite the discovery, the intriguing image on the cover, and the provocative subtitle—an emerging author such as myself was always in search of the new and unknown in literature—I approached the book with trepidation. My fear was that—just as in other books about Africa written mostly but not exclusively by Western writers—I’d find in this a story that would only perpetuate stereotypical depictions of Africa. A story that justifies colonialism, the looting of an entire continent, slavery, and other iniquities. And in fact, Ouologuem’s work, with its portrayals of profuse violence and devastating wars, with its profanities, did appear to live up to my frightened expectations—which caused me to stop reading, abruptly, after my first attempt. Still, the novel would not let go of me. There was something about the work that tempted me to overcome my initial resistance, set aside my assumptions, give the book a chance, and immerse myself in the story.

One day, I adjudged myself ready for this reading experience, open to whatever it would bring. I picked up the novel again and started to read. A unique, almost overwhelming experience. I tumbled through the world of the author, every page and every paragraph presenting me with a deluge of stunning images, each one more astonishing than the last. Violence was juxtaposed with unparalleled beauty; an original image was followed by an even more unusual one. As if the writer were on a mission to compel me and the world to acknowledge his genius, to share in his fury, resentment, love, bewilderment.

I read about an African empire, Nakem, and its dynasty of ruthless and devious rulers, the Saifs, who employed every means to hold onto power from their rise in the thirteenth century to their fall in the twentieth. I had something unique here in my hands, I thought. Like any writer confronted with a formidable work, first a huge sense of admiration came over me, followed by profound jealousy. But more beautiful than all of this was the wonderful feeling that, thanks to my curiosity about the marvels of literature, I had somehow discovered this work. Ouologuem became my writer. There was that feeling that the author is addressing his words exclusively to you, that he is entrusting you with his secrets, love, anger, and sense of wonder. The Senegalese novelist Mohamed Mbougar Sarr must have had the same feeling when he read Ouologuem for the first time, which then birthed his Goncourt Prize-winning novel The Most Secret Memory of Men. In Sarr’s 2021 novel, a Senegalese writer, Diégane Latyr Faye, goes in search of T.C. Elimane, an elusive compatriot whose book had been celebrated in an earlier time only to be undone by controversy and disgrace, and who subsequently disappeared into a “chosen, radical exile”.

Speaking of wonder, here is Ouologuem describing the love scene between Tambira and Kassoumi, two of the characters in Bound to Violence. Listen to this song:

“The leaves murmured as a light breeze brushed over them; naked in the tall grass, they mingled their sighs in consent. Transfigured and half delirious, conscious of nothing but their possession of each other, of their profound penetration, they lay enlaced, saturated with the mingling of their bodies, the drunkenness of their movements, raving, panting, tense from head to foot with passionate expectation. The woman carried the man as the sea carries a ship, with a light rocking motion, which rises and falls, barely suggesting the violence below. In the course of their voyage they sobbed and murmured; their movements accelerated, generating an unbearable force. The man groaned, he allowed his weapon to go faster, deeper, stronger between the woman’s thighs. The venom spurted; and suddenly they felt suffocated, on the point of explosion of death – an instant of intolerable joy, chaste and wanton – terrifying. They awoke from it vibrant, maddened, silent; weary and drained, with a humming in their ears, sated, obsessed, for they still felt possessed one by the other.”

Apart from the exuberance of the writing, Ouologuem did something unheard of in African literature. Born and raised in the predominantly Muslim country of Mali, Ouologuem had foregrounded a given that many people in West Africa, if not in the entire continent, live with: the presence of Jewish people in society, and of Jewish clans who are a centuries-long part of the African reality. In my family on my mother’s side, the Dukulys, members claim to be direct descendants of Jacob. Ouologuem no doubt grew up with stories of the Jewish presence in Africa, and these must have inspired him to write about an African-Jewish dynasty that ruled over the fictional kingdom of Nakem-Ziuko. The name sounded mythical, like music in my ears.

Here is the author telling us about that dynasty:

“The Lord – Holy is His Name! – showed us the mercy of bringing forth, at the beginning of the black Nakem Empire, one illustrious man, our ancestor the black Jew Abraham al-Heit, born of a black father and of an Oriental Jewess from Kenana (Canaan), descended from Jews of Cyrenaica and Tuat; it is believed that she was carried to Nakem by a secondary migration that followed the itinerary of Cornelius Balbus.”

*

Literature has a universal power of expression, and the work of one author can influence that of another, as is the case with Bound to Violence and The Most Secret Memory of Men. Indeed, the whole history of literature is the attempt by one author to respond to the work of another. That’s why the answer given by the African American writer Ralph Wiley to a question from Saul Bellow was so telling. “Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus?” Bellow asked. “Tolstoy is the Tolstoy of the Zulus. Unless you find a profit in fencing off universal properties of mankind into exclusive tribal ownership,” Wiley replied. It being true that literature belongs to us all, Ouologuem was prepared to fully leverage that freedom by making use of many different influences in his work, as if he felt at home in the literature of any time and place. By exploring Jewish mythology, which was part of his reality, the writer was also indicating that he was influenced by Jewish tradition and writers, among many other influences, foremost being his African tradition.

But it was exactly for this interconnective approach—this inclusion of many literatures in his work, the liberty he took with these influences—that he was accused of plagiarism. The accusation came three years after the publication of the novel and immediately after the English translation in 1971. The response of the literary world was swift and decisive. The man who had appeared on various media outlets in Europe and America, and who was feted and heralded as the future of African literature, had turned out to be a fraud, according to the accusation—a plagiarist masquerading as an intellectual. Bound to Violence was promptly pulled off the shelves across Europe and America. The allegations were that Ouologuem had taken, verbatim, passages from Maupassant, the Bible and the Quran; and from many other writers, including André Schwarz-Bart’s The last of the Just, and Graham Greene’s It’s a Battlefield. Doors were shut in Ouologuem’s face; he was shunned by the very public he had impressed and shocked with his prose. Every attempt by the writer to explain himself failed. In his defense—he had to say something—he reportedly said that he had used quotation marks around the contentious passages, so that the reader would know that they did not belong to him. He might have claimed that the passages he used from other writers and weaved into his own work were an attempt to play with influences—a new way of writing. But no one was listening. The damage had been done, and it was final.

Unique works of literature trigger deep amazement, and some suspicion: is this the work of a single mind? This must have been especially so in the case of a young black man who exhibited arrogance and confidence on every page. Ouologuem was not yet thirty when he authored his remarkable novel. No doubt, some felt that something did not add up and that there were things concealed from critics and readers pertaining to his work—a secret, a scandal. Another work by a gifted African writer was also a source of much controversy: The Radiance of the King, by Camara Laye. The Guinean faced accusations that he was not the real author of the 1954 novel, supposedly because the work was too singular for someone of Laye’s background and education. Perhaps part of the negative responses to these two writers had to do with the period, and the prejudice regarding achievements by people who had endured a history of colonial subjugation and slavery.

But these examples, especially in Ouologuem’s case, betray a failure of the literary establishment: the rush, sometimes, to erase or silence a writer who does not conform to established norms. A writer who does away with these norms, who sidesteps or crushes them underfoot, is bound to be misunderstood or punished for these bold transgressions. And if such a writer happens to come from among the formerly colonized—from a world that’s often presented in a negative framing—the punishment is severe. And few have been as misunderstood as Ouologuem. Many in his African tradition failed to understand him. Here was a writer who, in biting satires, seemed to mock the efforts of African intellectuals and artists who, faced with blatant racism in the West, fell back on the only option left to them. They took pride in their histories, which had been dismissed as absent or bereft of great deeds; and took pride in the color of their skin (denigrated or undervalued next to European beauty standards). Thus the Négritude Movement was born. Its founders, the Nardal sisters Paulette and Jeanne, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Léon Damas and Aimé Césaire, sang the African past into life. Proponents of this movement, such as the Ivorian poet and novelist Bernard Binlin Dadie, would compose what would amount to an anthem for Négritude: “I thank Almighty God for having created me black / For having set upon my head the world…” But Ouologuem held no truck for such romanticization of the African past. As he showed in his novel, violence and war has written the continent’s history just as much as love and beauty.

*

The fact remains that many writers have been inspired and influenced by those that wrote before them. We have One Hundred Years of Solitude thanks to the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier, whose novel, The Kingdom of This World—a book which in turn was inspired by the African diasporic society in Haiti, and by extension, Africa—launched the entire tradition of Magical Realism. Ouologuem’s accusers based their case on a cursory examination of his work. To my mind, Bound to Violence, with its bold and propulsive energy and mythmaking, is perhaps even greater than the Graham Greene novel that was supposedly plagiarized. To find the deeper influences on Ouologuem, we must look to another novel he also utilized: The Last of the Just by André Schwarz-Bart. Or to the Polish-Jewish writer who is one of my major influences, Isaac Bashevis Singer—especially his novel, Satan in Goray. Bound to Violence seems more similar in tone and structure to these two novels than to any other book. Ouologuem must have discovered, just as I did on reading Singer and Schwarz-Bart for the first time, how strongly Jewish rituals resembled his and mine. This, I believe, is what drove Ouologuem to take these influences and incorporate them in his work. After all, literature is a playground where everything is possible if the writer so chooses.

*

After I’d read Bound to Violence, I wanted to know more about its author, just as Sarr and many others must have felt on encountering the Malian writer for the first time. Ouologuem, I learned, was a Dogon, an ancient people with their own unique cosmology that’s been widely written about. He was born in 1940 in Bandiagara, the Dogon capital located in present-day northern Mali, the only son of a rich landowner. In Paris, he studied sociology, philosophy, and English at the prestigious Lycée Henry-IV; he then obtained a doctorate in sociology from the École Normale Supérieure. Between 1964 and 1966, he taught English at the Lycée Charenton in Paris. Two years later, in 1968, Bound to Violence was published, winning its author the Prix Renaudot, one of the most important literary prizes in France. On the internet, I saw no indication that Ouologuem was no longer living, but I never found out his location. He had also written a few minor works: two romance novels, the searing booklet Lettre à la France Nègre (Nalis, 1969; reissued by Le Serpent à Plumes, 2003), and the erotic novel Les Mille et Une Bibles du Sexe (Le Dauphin, 1969; reissued by Vents D’ailleurs, 2015). Both published before the controversy. I had to have the erotic novel, I decided. After some searching, I got my hands on a copy. The writer’s voice was unmistakable. I recognized the exquisiteness and the brilliance, but the book did not attain the mastery of his infamous debut. The author’s later silence, and retreat to his country of birth, underscored the pain and despair he must have felt in the aftermath of the plagiarism allegations. He died in 2017. Ouologuem had been cast into a sea of sharks that didn’t appreciate him for the great writer he was. Perhaps why withdrawing into silence was the only option for him.

My first reaction after learning about the controversy was indignation. This was not someone trying to steal passages from other works because of some inferior talent. Didn’t the detractors get the joke he was playing on the literary establishment? “See what I can do with your sacred texts,” Ouologuem seemed to be saying. “See how familiar with, and well-versed I am, in these texts.” He was being provocative, calling the literary world to witness this brazen exhibition of intertextual play and his doing away with conventions. He didn’t stop there. To the tradition that had molded him, the African tradition, he seemed to be saying, as he swept through centuries of African history in a few hundred pages: “My Africa, with your storytelling tradition: see how I play with your myths, see how I overstep your boundaries and break your taboos. See how far I go.” Those who shut Ouologuem out failed to see that with the singular Bound to Violence, he does away with every literary convention.

A sense of indignation, not unlike mine, must have been what spurred Sarr to write his novel. He wanted, like me, to counter the false image created by the accusation that forced Ouologuem into hiding. To rehabilitate the writer, to correct the erasure of someone whose work defied convention and thus grossly misunderstood. Sarr must have wanted to bring Ouologuem to life, to show the world the myth that was the man and the implications of a life ruined by cancel culture. Like me, Mohamed Mbougar Sarr might have wanted to meet the great man too. And perhaps because he could not realize this in reality, he turned to literature, another possible and effective means of encounter. Sarr’s protagonist goes in search of a mysterious author—as I would in real life, some years after reading Ouologuem.

While doing research for my fifth book, The Black Napoleon (Dutch, 2015) or The Emperor’s

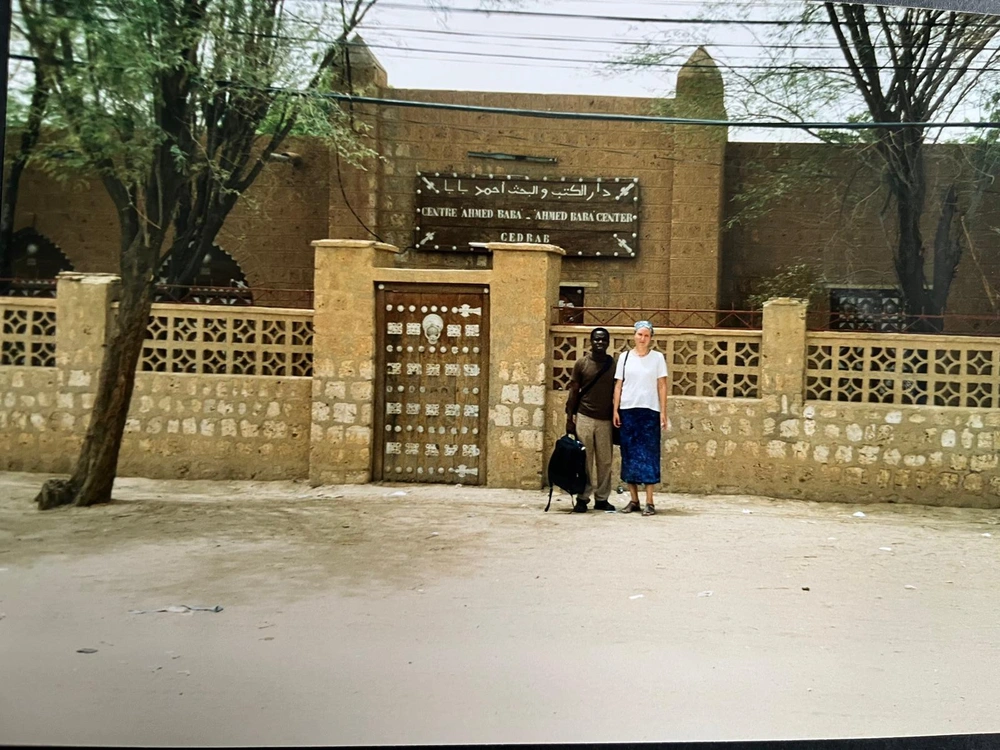

Son (English, 2024)—a novel about Emperor Samori Touré, the resistance hero who fought both French and British Colonialism—I spent the summer of 2003 in Bamako, Mali. I was on my way to Timbuktu, to read manuscripts at the famous Ahmad Baba Center, named after a scholar whose fame spread to all West and North Africa. Some of those ancient manuscripts, according to family lore, had been written by my ancestors. There’s a story handed down in my family that one of my ancestors, a renowned Islamic scholar named Talata, left Timbuktu centuries ago and moved southwards, settling in a town on the banks of River Jon, a tributary of the Niger. The town was Musadu, or Moussadou, a famed historical place and source of many legends, now in Guinea Conakry. Talata married a local woman of the Kpelle people and had three sons, and I’m a descendant from the house of the youngest.

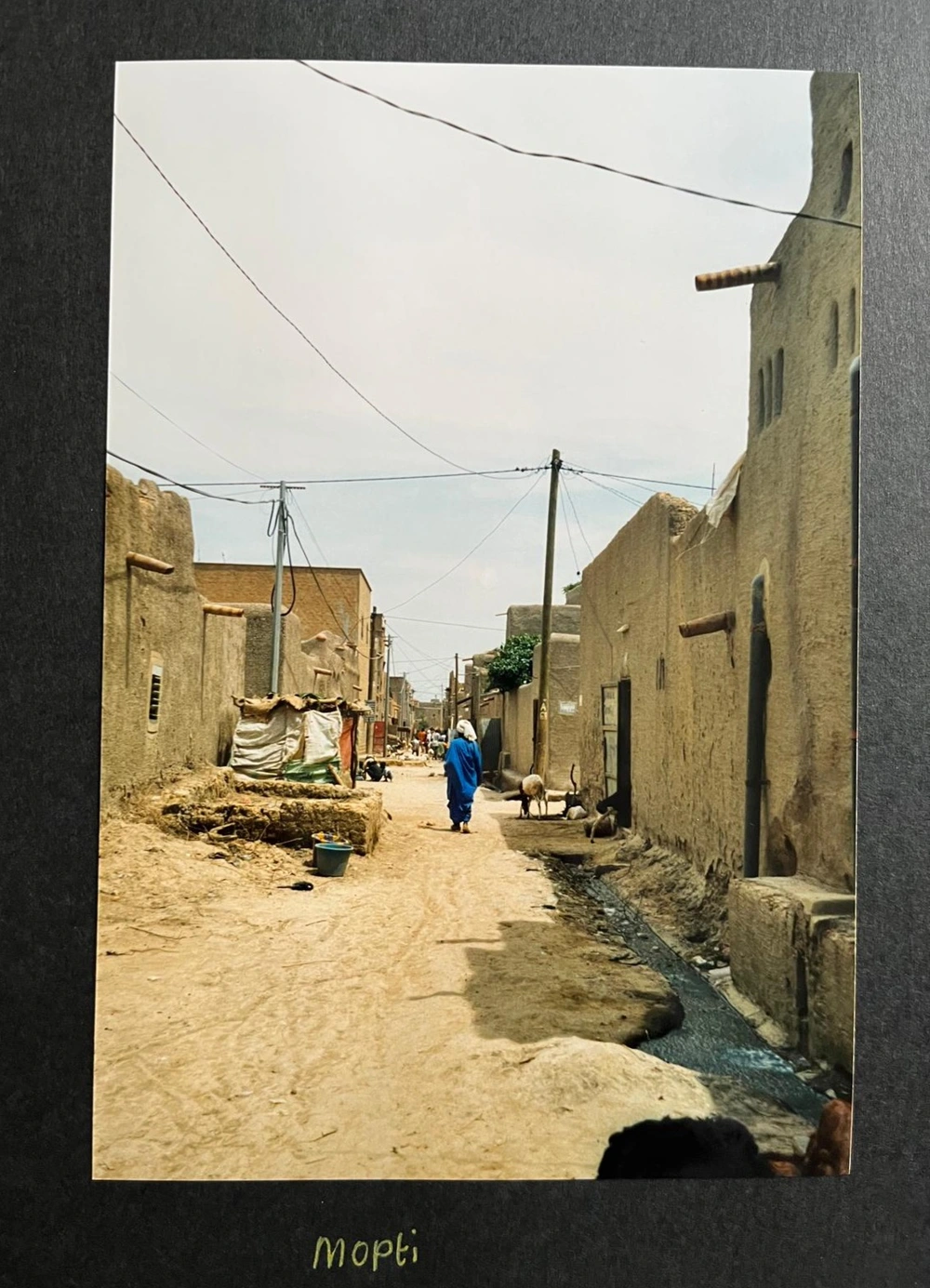

Once in Bamako, I had the easier option to take a flight to Timbuktu. However, for reasons that were then unknown to me but that would soon become clear, I travelled by car. It was a journey that would take me through Segu, a city immortalized by Maryse Condé in her historical novel of the same name. We drove through the Dogon country with the road terminating at Mopti, a city at the edge of the desert, from where boats loaded with goods set out for Timbuktu. It could not have been a coincidence that—perhaps guided by the hands of the ancestors—in a conversation with one of my local contacts, I happened to inquire about Ouologuem and was told he lived in the suburbs of Mopti, in Sévaré to be precise.

My journey—on the surface, an attempt to trace my heritage—had in fact been driven all along by a deep longing to meet the man and hear his story, including the effects of the controversy of decades before. And here I was being told that he lived just a stone’s throw away.

I should have let him be and gone on with my life, with the contentment that at the very least, I had entered the country that had birthed him—because our heroes, especially literary ones, are to be admired from a distance and not close up, in order to avoid disappointment. No writer can conform to the image that an admirer creates of him or her. I should have known that. But the man in whose honor I would decide to name my third novel Bound to Secrecy was so close. The temptation was immense, irresistible. I had to see him.

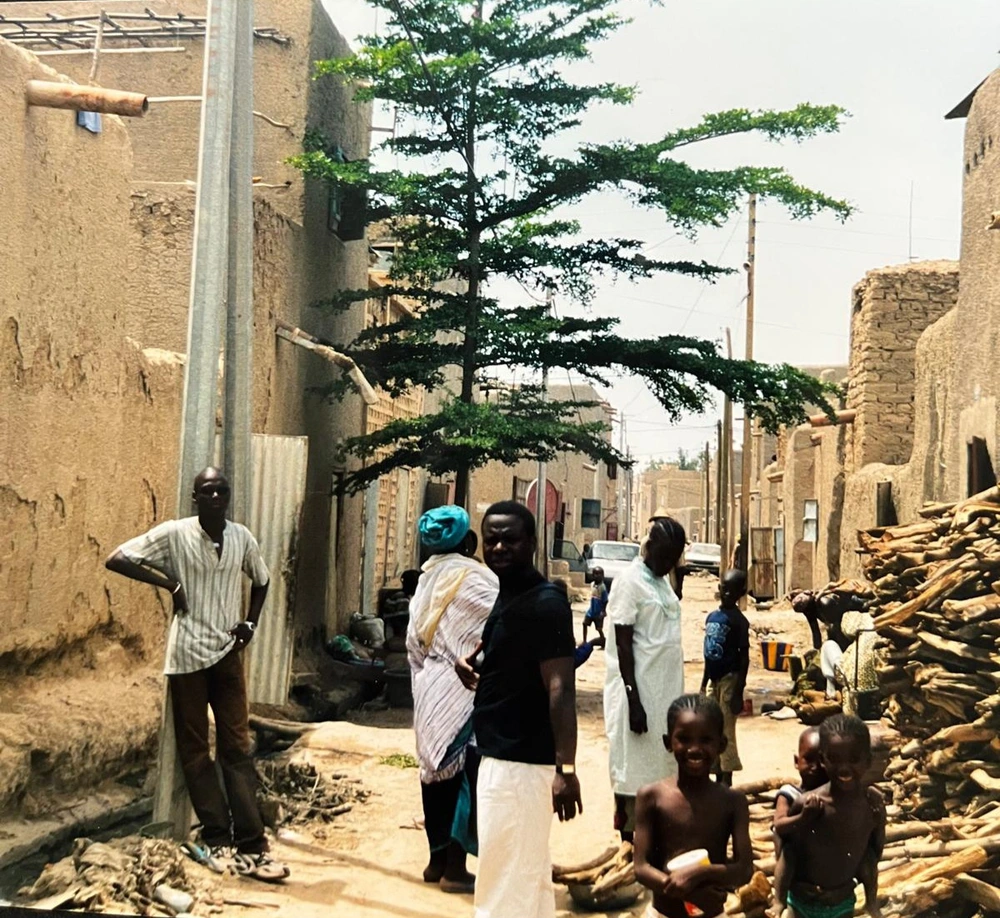

Mopti has clear traces of Sahelian architecture—beautiful clay buildings and homes of mudbricks, adobe plaster and wooden logs—which have made Malian cities like Djenne and Timbuktu world-famous. I expressed my desire to meet Ouologuem. It was possible, I was told, but I received this warning beforehand: for the entirety of our meeting, nothing should give away that I came from the West. Ever since the accusation that ruined his life, Ouologuem had wanted nothing to do with the West. “You may want to dress in traditional African clothing when you visit him, not a suit or a shirt,” my contact said. “If he suspects you’re a Westerner, you won’t get a single response out of him.”

I rode with my contacts to Sévaré to meet the writer. We found him seated on the veranda of his family home. Ouologuem was dressed in a simple kaftan paired with an embroidered kufi cap of the type my father wore. He was serene, unperturbed by our arrival. In his eyes, which were directed at me, I caught hints of the genius whose work had made such an impression on me. After introductions by men he knew, who said that I was from Liberia and that I was a writer, he inquired in English about me. I told him a bit about my life and about my father and grandfather, who were both Sufi mystics. Smiling, he said he was a Sufi himself, of the Tijaniyah order. I told him that my father and grandfather were of the Qadriyah order, but I added that my uncle, a poet, was a Tijaniyah Sufi, just like him. “The two ways are the same, you see,” he said, and then he burst into a generous and hearty laughter. For a second, the man who exhibited such exuberance in his writing revealed himself to me. He added that there was however a period in the history of West Africa when tensions rose between these two denominations. Ouologuem seemed at ease as he talked about these subjects.

I should have confined our conversation to this theme of Sufism, which seemed to interest him so much. But, anxious to connect with the man who had been such an inspiration to me, I made the mistake of trying to move the conversation to the subject of his life and his love of literature—not Western, but African or World literature. The writer stuttered. He regarded me with questioning eyes, tried to say something, and then fell silent. After a while, he thanked us for coming to see him, but said he did not wish to address his past or to go into any conversation about literature. He’d apparently seen through me, I thought. I had hoped to speak with him for hours, to unearth the buried treasures behind the enigma that he had become. But he seemed not to be sure about me anymore; he probably thought that I was not who I said I was but a Westernized journalist with a double agenda, someone on the hunt for sensationalism and salient stories. It was time to leave.

Though the visit was brief, I had managed to peek into the life of this reclusive author. But I realized at the same time that I should have let him be and not disturbed the peace he had cultivated, and the solitude with which he had chosen to live. He was still very wary of the literary world that robbed him of a future that had held so much promise.

*

Ouologuem’s life—especially his struggles in the shadows, which must have been bitter and hard—shows us the pitfalls of erasing a writer. Many writers and artists are grappling with the consequences of being misunderstood, of being erased or cancelled. Others are threatened, some end up in jail or lose their lives. We are fortunate that in Ouologuem’s case, the damage was not permanent—at least not in terms of his legacy—though his life had been ruined. Even as I was discovering him, even as Sarr was discovering him, other writers and scholars, including his family, had been working hard, through essays and translations, to rehabilitate him. It is a testament to the enduring power of literature, the inherent longing to express oneself without fear of retribution, that a voice that was silenced would, after decades of absence, begin to come alive again. It is a credit to the efforts of his admirers and those who hold the word dear.

Ouologuem showed us a pathway to the future of literature. We should embrace it by being as fearless as he was, and when necessary, unconventional. In the end, he was a true chronicler in the African tradition. We hear in his scathing words, in his rage and anger, in his brilliance, echoes of the chants sung by the djelis—the griots, the guardians of the word, as Camara Laye rightly called them—and their mastery of the art of eloquence.

That must be what truly matters in the end, the mastery of kouma – Mandé for word.