In her late thirties, while on a weekend ski trip, my mother began to bleed so heavily that the blood seeped through her Gore-Tex pants. On the drive to the hospital, she wrapped a garbage bag from my father’s trunk around her torso and held herself until her cramps intensified so badly that she begged him to pull over. In a gas station toilet, the fetus partially expelled itself, and a few hours later she underwent a D&C, her uterus scraped clean.

My mother, a nurse, told the story repeatedly and unabashedly throughout my adolescence, along with those of three other (less traumatic) miscarriages she endured before bearing me. “Such were the hazards of becoming a mother at nearly forty,” she always said with a shrug.

At home in bed in March 2020, I experienced symptoms nearly identical to those my mother had described. I bled profusely — through bedsheets and a mattress pad, through super pads and tampons every hour — until I sat on the toilet and heard a small something plop, like a pear falling from a drooping tree. Remembering my mother’s story, I fetched wooden chopsticks from the kitchen and fished out a bloody, jellied blob. It had two glistening plastic arms protruding from either side, like a crucifix.

It wasn’t a miscarriage. It was my IUD.

I’d had it inserted four years earlier. Under the duress of the Trump presidency, and because of my history of inconsistency with birth control pills and my fear of looming abortion bans, I decided to take control of my uterus. I was not alone. Insertions of IUDs, short for “intrauterine device,” increased 21.6 percent after Trump’s election. Planned Parenthood reported a 900 percent increase in demand.

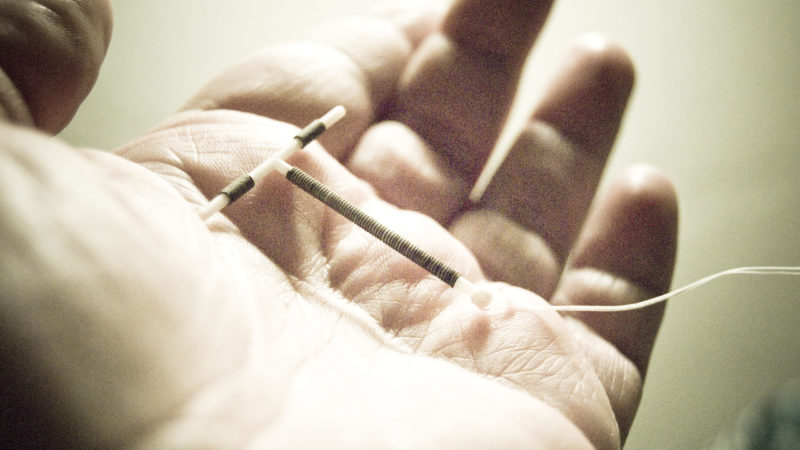

Early IUDs were made of silkworm threads, shaped first as rings and then as coils, each with varying rates of success — and infection. In 1969, the IUD first assumed its iconic T shape, and copper, the active component of metallic IUDs, was found to inhibit pregnancy. IUD usage increased during the women’s liberation movement, then plummeted sharply in 1971, after a new kind of IUD called the Dalkon Shield, which was shaped like a horseshoe crab, wicked bacteria into the uterus, resulting in severe PID, sepsis, and sometimes infertility. Paragard, the copper IUD still widely used today, entered the market in 1988, followed by Mirena, the first device to release levonorgestrel, which thickens cervical mucus, in 2001. Skyla, a low-dose hormone option, followed in 2013.

By 2016, IUDs were hailed as one of the safest and longest-lasting birth control options. I chose Mirena. Upon insertion, I cramped for a day, then never noticed the device was there. After a year, my periods slowly stopped. Absent this inconvenience, I felt carefree, liberated from the basic functioning of my reproductive biology. Even when I began spotting frequently in late 2019, I chalked it up to my inconsistent-to-nonexistent menstrual cycle. Until that chopsticks-in-the-toilet-bowl day.

I learned later that the cause of the expulsion was uterine fibroids, noncancerous growths that can be as small as beach pebbles or as large as pétanque balls, causing everything from pelvic pain to excessive bleeding. I needed outpatient surgery — a hysteroscopic myomectomy — to chomp away the smallish, likely hereditary masses.

I have controlled my fertility for nearly half of my life, since I started the pill at fifteen. I never questioned what mechanisms enabled its regulation or what this has meant for my body; I only cared that they worked. When my IUD expelled itself, I saw that the personal and political goal of bodily control, while worthwhile, is an illusion.

“Your body is a battleground,” goes the frequently reprinted Barbara Kruger koan. Her point, originally made in a poster for the 1989 March for Women’s Lives in Washington, is that someone is always vying for control over women’s bodies, including women themselves. Under control of any kind, whether legal or medical, the unruliness of our bodies is thrown into relief. What’s often lost among the abstractions and metaphors and restrictive legislation, and even the rhetoric and birth-control devices that enable women’s liberation, is this: no matter the intention, bodies rebel. They’re bloody and brilliant, with agendas of their own.