When I saw John Chiara’s photographs of California for the first time, I thought of wildfires. It was still fire season in late December of 2017, and smoke from Montecito was blowing up to San Francisco. Each day I counted as the acres of flame grew and grew. I spent much of my time looking at footage of the fires. I’d seen the Getty Museum surrounded on all sides by flames on CNN.

I had just moved west, from New York to San Francisco, for a reporting job. Wildfires were new to me—their size, their improbable beauty, their terror. I was transfixed. Such fires constitute their own genre of photography. I think in particular of Los Angeles Times photographer Marcus Yam’s widely circulated photo of palm trees burning in Ventura, the entire sky hell-red behind their thin trunks, ruptured with orange.

John Chiara does not take pictures of fire. But his photos evoke fire photography. They have its same otherworldly quality, enchanting and disquieting colors, and massive scale.

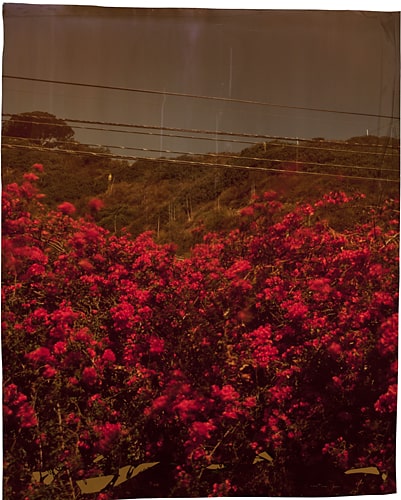

The San Francisco-based artist, whose work focuses largely on California, photographs landscapes using an unusually toilsome method. He builds giant cameras, which are often so big he has to drag them around on the backs of trucks or attach them to his trailer. Some of his subjects are classic California fare: trees in the snow, red flowers in a field and the Pacific glinting with sun, gas stations and power lines and the pastel houses of San Francisco’s Sunset District and the strange shapes of palm trees.

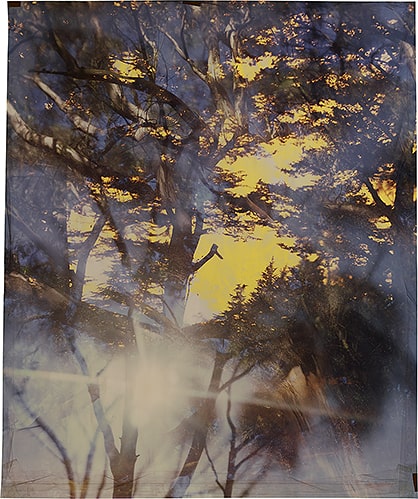

Even in these familiar scenes, though, there is something distinct: a sense of motion and time compressed into a single frame, resulting from his unusual process. His cameras are much like camera obscuras, functioning simultaneously as camera and portable darkroom. He uses photographic paper rather than film, which means there is no grain or pixelation or zoom. Light leaks and chemical damage and warped edges are absorbed into his work. Long exposures allow light to bend and stretch, then freeze. The paper captures this transition, which lends his images a sense that they are moments on the cusp of change, perhaps disaster.

In December, as fires continued to ravage southern California, I was obsessed with one of Chiara’s shots in particular. I discovered it online by chance: Agua Dulce Canyon Road at Route 14, Santa Clarita (2013). The photo appears in his recent monograph, California, published by Aperture in October 2017. It was shot vertically and shows brush on a hill, everything stained red and yellow and orange. In the foreground, white trees stand out against the red-gold, like an x-ray or small bones.

***

Chiara has been shooting in California since he was nine years old . That’s when he got his first camera, a gift from his dad. In a few hours, he had used up several rolls of film that were supposed to last months. Chiara was born in San Francisco and raised outside of Walnut Creek. He attended the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, where he studied painting and photography. After graduating in 1995, he moved back to California with little money, first to live with and work for his parents. When he saved up, he moved to Oakland. After three years, he moved to San Francisco, where he has remained.

I met Chiara in the co-op where he has lived and worked since 1999, on the edge of San Francisco’s Mission District. Across the hall from his loft and kitchen are the large silver freezers where he stores his photographic paper in massive silver freezers. Freezing preserves the color of the paper, he told me; before he shoots, he has to defrost the paper. If he doesn’t, it becomes discolored and warped. He learned the hard way, he told me.

Unassuming, soft-spoken, and bearded, Chiara was just back from traveling in India when I first met him. We sat down to have tea. He told me he had spent part of the fall in New York, mostly taking pictures around One World Trade Center. “New York is different,” he said. “It’s darker and you have to move more quickly. Sometimes you just have to jump in and take a spot. It’s a little more opportunistic.”

While Chiara often travels around—he’s been in Mississippi a few times recently and will be back in New York for the spring—his home base is California. He likes going back to places: Tahoe, Pacifica, Portrero Hill. San Francisco is changing a lot, he noted, as are its people. “What’s underlying that change is what makes the city special,” Chiara said. “The identity of the city is becoming more abstract and in flux, even on a street level.”

Chiara started building his cameras in part because he wanted to slow down time. “With these cameras, you get a different type of image, one that’s slowed down a lot,” he said. In college, he took inspiration from shooting with 4×5 cameras—mostly more abstract photos, pictures of wax or leaves. He was shooting contact prints, or prints made by directly transferring negatives onto paper or glass. Struck by how charged they were, compared to the the photos he usually saw, Chiara wanted to see if he could preserve that direct quality at a magnified scale.

Some of his photos are slowed down to a dream-state. 23rd Street at Carolina Street, San Francisco, 2004 depicts a city bathed in pink-blue. It feels barely real, emerging from the edges of the frame. It’s hard to tell what is sky and what isn’t. It feels true to San Francisco and all of its strangeness.

San Francisco, and California broadly, are enduring subjects for him. His book is called California, but he says it’s not meant as a definitive representation of the whole state. Rather, he hopes the photos’ arrangement creates a sense of his own wandering journey. The book is organized loosely around the idea of a road trip, south to north.

“[They] weren’t planned,” he said of his California forays. “It’s been a slow, meandering process of dragging the equipment throughout the state, always trying to expand my terrain, wherever I’ve had the opportunity to go.”

***

Can you picture The California Photograph? It was on the wall of someone’s college dorm room: a Malibu shoreline and a surfboard in shadow. Or maybe it was a view over Highway 1. Or palm trees on a Los Angeles drive, backlit by ethereal streaks of pink. Sunsets over the ocean, again and again and again.

The California Photograph is almost as old as photography: the new art form became entangled with the European-American settling of the American West. In 1848, nine years after the daguerreotype’s invention in Paris, James W. Marshall found gold at Sutter’s Mill in California. Flocks of would-be miners came west, and so did photographers in covered wagons. An estimated 300,000 settlers moved to California between 1848 and 1854.

“Two great myths or crazy dreams—filling your pockets with the most precious metal and fixing your image in metal—became a reality in the mid-nineteenth century,” Luce Lebart writes in the catalogue for a Canadian Photography Institute exhibit called Gold and Silver: Images and Illusions of the Gold Rush. “The affinity between these latter day argonauts and the daguerreotype, the first commercially successful photographic process using a silvered copper plate, was immediate and intense.”

Over the next decade, early photographers took portraits of miners—stoic white men with pickaxes and whiskey—and the camps where they lived and worked. They also panned out to the broader landscape, which came to capture the imagination of people back east. In 1861, Carleton Watkins took some of the first photographs of Yosemite Valley: mammoth-plate images of a place the likes of which had rarely been seen by outsiders. Two years after being shown the photos by a private collector, Abraham Lincoln designated Yosemite as a national park two years later, in part because he’d seen those photos.

Others followed in Watkins’ (and his mules’) footsteps. Eadward Muybridge captured expansive scenes of Yosemite. He also took photographs of the area around San Francisco, too, including an astounding panorama of the city from a hill on California Street that is often cited as the first image of this city of hills. Later, Ansel Adams photographed the same territory—and especially Yosemite—to mass popular appeal, and it became etched into the consciousness of twentieth-century America. By 1920, California had been sold to onlookers back East.

The state continued to saturate American eyeballs and imaginations. Man-made landmarks emerged, and were photographed: the Hollywood Sign, The Golden Gate Bridge, Alcatraz.

Flipping through California, you can see influences of early Western photographers like Watkins and Adams, whom Chiara studied in college. “California—the whole West, really—has a rich tradition with landscape photography that follows the way painters painted the West, those majestic paintings that influenced people back east,” he told me. “They portrayed the West in a very dramatic way from intense vantage points.”

By using historical technology, Chiara follows in the tradition of those early photographers. He drags heavy equipment up hills to those photographers’ same viewpoints. And some of his photos do have that majestic quality.

Yet Chiara’s work is separated from the classic California Photograph by its imperfections. The edges of his photos are often crinkled and wavy, evidence of the photographic paper warping. Streaks of light interrupt the frames. This damage lends his photos a surreal quality that can be sinister at times. It’s hard to place, but I thought of this undercurrent when I happened upon another image of his, Highway 1 at Moon Lake (2014). The photo is a a diptych of trees reflected back in a the mirror of a lake. In the corner, there is a splotch of gray light that looks like smoke rising from the ground. The photo is arresting, but it holds the possibility of terror, too.

Chiara is interested in what he calls visual memory. He tells me that he loves “the way something certain places can be burnt into your memory and make you nostalgic—like that feeling you get walking home from school.” He wants to take pictures that incorporate the past and the present all at once.

He spends more time plotting out which part of a particular parking lot will be best for shooting the sun as it disappears than actually shooting. A lot of people would find this maddening, but he likes it.

I told Chiara that his photos made me think of wildfires. He knew immediately that I was thinking of Santa Clarita, the photo that had first drawn me to his work. “I was driving along Highway 14 and I saw these landscapes where a fire had happened, where there’d been a fire a few years before,” he said. He wanted to capture the burned-out, scarred land, but he did it using a negative, in a an attempt to capture something that used to be there. The black trees turned white and they spread like ghosts against the flame.

Later, months after I first saw it, I realized that it had inadvertently become a photo of the future. I noticed that the title was oddly familiar—Santa Clarita meant something to me. I realized that I had written about a fire there in December. It had burned again.

***

The week I first moved here, the city was in a haze. Smoke was still lingering in the air from wildfires in the wine country. Forty-five people would die, that week or later. I had come out here from the East, looking for something undefined, like a lot of people. I was suddenly proximal to a kind of devastation that was new to me, and hard to comprehend.

I have a sense here of living constantly on the edge of peril. In my house, we keep gallons of water in case of an earthquake, enough for four people over the course of three days. We are waiting and watching for a tsunami, though apparently we’re lucky because we live far enough from the ocean. There will be more fires soon.

For now, we still have the views. Standing on top of Twin Peaks, on a day when it’s sunny and foggy at the same time, I draw in my breath and wonder at all the city’s astounding angles. Everything unfolds below me, pastel and sharp.

***

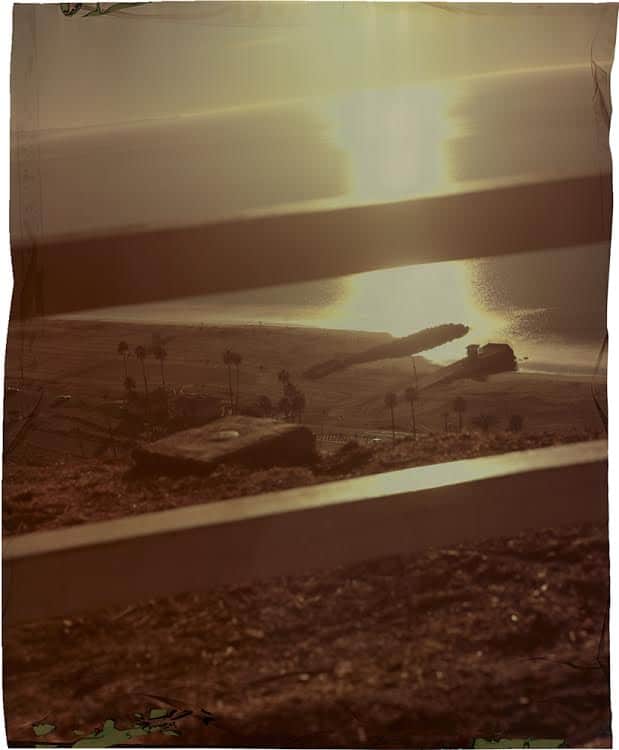

Mount Holyoke Avenue at Pacific Coast, Pacific Palisades (2013): a Pacific beach at sunrise or sunset, palm trees and a jetty. In the very distance you can see a couple strolling. Yet its red-sepia tone washes out the scene. It looks like a dated image of the atom bomb splitting the sky.

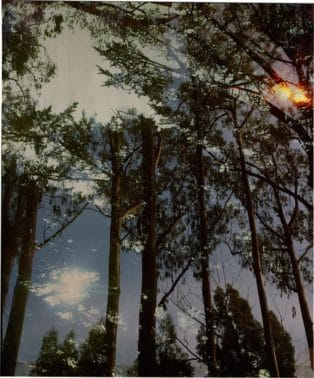

Bunker Road; Simmonds Road; Fort Barry, Marin Headlands (2015): light bursts through a gap in the trees, or in the shadows of the trees. Maybe it burns; a hot center of light melting through the blur of branches and the dark sky. It’s a candle or kindling.

***

I drive south on Highway 1 to meet Chiara in Pacifica on a February afternoon. He is shooting pictures of Rockaway Beach, his boxy camera propped just behind a seawall in the parking lot of the Sea Breeze Motel, which advertises vacancies in neon.

Pacifica is like a postcard with beaches tucked in between green hills and dramatic rocks framing the broad swath of the Pacific. Chiara is trying to shoot the glare on the rolling swells—an exercise not unlike trying to catch fire on camera. He squints and points the lens at the light, trying to get it before it changes or disappears. He wants to slow down the harsh dancing of the sun. Today, he asks me to help him. He’s built a new camera, 40 by 50, and he’s testing it out.

I pass him filters in various colors of yellow, and I time his exposures on my phone. He waves his hand in front of lens as he shoots. “It’s something I’ve found from shooting the glare, that if you don’t break it up, it comes out as long streaks,” he says.

The glare is so bright I have to close my eyes. It’s about 4:30 in the afternoon, in winter, and he’s waiting for the right moment before the sun disappears behind a cliff.

Each picture is a labor. In fact, he only takes two in the hour or so that we’re there. It’s a bit of an experiment, given that he’s using a new camera. But when the moment comes, he moves quickly and precisely, and I try to keep up.

“This is the best time,” he says, and I agree as the light goes from harsh to gold.