By Kaya Genç

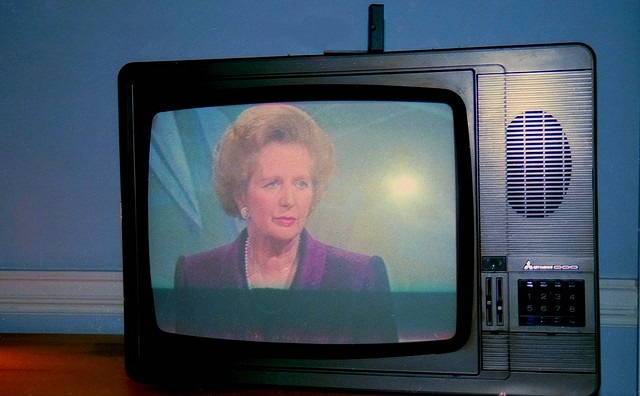

At the end of World War II, European and British politicians began instituting what would come to be known as the “post-war consensus,” a set of policies that challenged the concepts of private property and competitive markets with socialist ideas. The investment of public money to construct a welfare system and set up institutions such as the National Health Service proved popular with the electorate, but it rubbed the ideologues of neoliberalism the wrong way. Headed by the Austrian-born economist Friedrich Hayek, the latter saw the abandonment of laissez-faire economics as a fatal blow to the fundamental principles of liberal capitalism. With their romantic nostalgia for a golden pre-war era, Hayek and his circle gradually began convincing people to distrust regulated markets. In 1947 Hayek and a group of thirty-six scholars, journalists, and government officials convened at Mont Pelerin, near Montreux, where they agreed on principles for propagating a market-oriented free society. With Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power in 1979, the group achieved their moment of triumph.

Since then, the neoliberal narrative has defined British politics. It cemented itself as the de facto discourse of the Conservative party in the 1970s, and achieved bipartisan status in the country when Tony Blair’s New Labour also came to its defense. In modern Britain, what had once been a set of political beliefs held by a small group of intellectuals morphed into a set of power relationships that the writer Owen Jones dubs “The Establishment”.

Jones’s book about the phenomenon, titled The Establishment: And How They Get Away With It, is an extensively researched, beautifully written, and impassioned indictment of this imperfect system. Nevertheless, the book’s eponymous villain is a concept that, from the start, requires some explanation and defense. Is it even a valid concept worth writing about? After all, just because you discern patterns of movement in a group of people walking on a street does not necessarily mean that they are being controlled and determined from a hidden center nearby. The Establishment in the book’s title seems to refer to an invisible pattern of behavior and thinking, an abstract quality, which makes it a bit difficult for the reader to comprehend what it really means.

No one can point to a law that makes supporting neoliberalism a prerequisite to holding a powerful position in modern day Britain.

The problem with the notion of “the Establishment” is that it is both too broad and too narrow, too abstract and too concrete. The Establishment refers not just to a system of powerful political and economical relationships but particularly to those that, since the Thatcher era, have helped make neoliberalism Britain’s defining political narrative. The Establishment is to neoliberalism what the power relations among Soviet leaders were to socialism. The chances of a Thatcher critic, a vocal defender of a regulatory state and socialist policies, making it to the top of today’s British Establishment are next to nil.

And yet, however hard you look for proof that there is something like an Establishment—a concrete, palpable entity that fits its description—you will have to admit defeat at one point: no one can point to a law that makes supporting neoliberalism a prerequisite to holding a powerful position in modern day Britain. As a system of relationships between believers in an ideology, the Establishment is too airy a concept. And simplifying a set of complex relationships under such a vague heading raises the suspicion that the author is fighting a straw man.

Nevertheless, when you look at the shared features of the people who Jones interviews and identifies with the Establishment, a pattern does emerge. They have all prospered thanks to their defense of neoliberalism and their loyalty to its intellectual leaders; they have brought like-minded people around them in the course of their successful careers and got their motivation from a shared belief in neoliberal ideas; and they all inhabit the universe of the extremely powerful.

Jones, a columnist for The Guardian and the author of the unexpectedly successful debut Chavs, tries to use these power holders to expose the ethos of our neoliberal times. Neither in Chavs nor in this book has he written a theoretical treatise on neoliberalism. Jones is more Friedrich Engels than Karl Marx. The spirit of his books is more akin to the journalistic The Condition of the Working Class in England than to the theoretical Das Kapital. In The Establishment, Jones wisely chooses not to wrestle with the intellectual forefathers of the neoliberal ideology. He stays away from using an academic discourse and the resultant book, in its quixotic struggle against a somewhat absent referent, is a page-turner.

Jones has interviewed a number of current or former members of the Establishment, conducted extensive research in newspaper archives, and come up with compelling anecdotes and examples serving his argument about the rotten state of affairs in Britain. Those vividly reproduced interviews bring us from gastropubs in Islington to extremely posh offices in Mayfair.

In their aspiration to be more prosperous, outriders have become preachers of aspiration, and prospered as a result.

According to Jones, the most important component of the Establishment is a group called “outriders” who have earned this name thanks to their determination to protect the wealthiest elements of British society. Paul Staines, one of Jones’s first interviewees, is a good example. A young zealot inspired by Thatcher’s ideas during 1980s, he read Karl Popper’s The Open Society and Its Enemies when he was 13. After becoming a “bag carrier” to a Thatcher advisor, Staines worked as a broker in London for many years. He started a blog where he made a name for himself by airing the dirty laundry of Westminster politicians. Staines hates politicians (“I hate the fucking thieving cunts,” he says) but according to Jones, “it would be a mistake to see Staines as leading a crusade against Britain’s ruling elite: far from it. In fact he is an unapologetic outrider for the wealthiest elements of society.” A mouthpiece for his country’s plutocrats, he confesses to not being “that keen on democracy”.

In their aspiration to be more prosperous, outriders have become preachers of aspiration, and prospered as a result. Today, they hold key positions in parliament, the media, the banking industry, the police force, and the public services market, where companies compete to become beneficiaries of the privatization of services once provided by the state.

In order to inflict fatal blows to do-nothings, have-nots, and the so-called scroungers who live off the state, supporters of neoliberalism have also helped found powerful institutions like The Institute for Economic Affairs, which allocated money and effort to winning “the intellectual case” about economics. Jones interviews the IEA’s current director who tells him how, after Thatcher moved to Downing Street, the IEA came to “equip [her] intellectually in her first term in office.” The Adam Smith Institute (established in 1977), Centre for Policy Studies (founded in 1974 by Thatcher and Keith Joseph), St James Society, and other free-market organizations also helped lay the cornerstones of Thatcherism: “privatization, deregulation, and slashing taxes on the rich.”

Whilst perpetuating and defending a neoliberal vision of society, members of Jones’s proposed Establishment have also found increasingly more profitable uses for their intellectual labor. One striking figure among Jones’s conservative interviewees is Lord Timothy Bell. He made headlines in British newspapers last month when he called for the police to investigate Hilary Mantel on the grounds that she used her imaginative faculties to fictionalize “the assassination of Margaret Thatcher” in her latest book. “If somebody admits they want to assassinate somebody, surely the police should investigate. This is in unquestionably bad taste,” Lord Bell reportedly said.

In The Establishment, Lord Bell is interviewed in honor of his gift for simplifying complex ideas (such as Thatcher’s) for the masses. The well-connected, entrepreneurial-minded members of the ’68 generation might have made lots of money by commodifying figures like Che Guevara, but the Thatcherite outriders have out-earned them by a wide margin. Having worked as campaigner for the Conservative party in 1979—he was responsible for the influential “Labour Isn’t Working” posters—Lord Bell knew that the conservative message could be a very salable one if communicated clearly. As a campaign manager he effectively sold the idea that labor unions were bad for society, that only Tories could fight against their influence, and that a dogged determination to make money would help people earn money, although that last proposition mostly ended up making money for Lord Bell himself.

“Life was horrid,” Bell tells Jones, describing the darkness that was the pre-Thatcher era. “And she came along with a new idea, which was we don’t have to be like this, we could actually go back to where we were and be great again, but in a contemporary context. And the idea captured the imagination of a large proportion of the population.” According to Lord Bell, Thatcher’s popularity was a natural outcome of her being “just right.”

More interesting perhaps than the interview with Lord Bell itself, though, is Jones’s description of his quest to find his offices. After reminding us that his interviewee chairs the PR agency Bell Pottinger, whose client list includes the Pinochet Foundation and the wife of President Bashar Hafez al-Assad, Jones sketches out the view of the neighborhood that hosts offices of Lord Bell as well as numerous other figures of the Establishment:

Here Jones tellingly showcases the cozy circles in which Lord Bell and others like him live. But The Establishment is no mere condemnation of British politicians (Tories and Labour Party members alike) and their posh neighborhoods. As The Establishment continues, Jones casts an even wider net with his condemnations. In one of the most remarkable encounters in the book, Jones interviews Andrew Mitchell, the former chief whip of the Tory party. Mitchell had been forced to resign from his post in 2012 after a Downing Street police officer accused him of yelling slandering words after getting stopped for wheeling his bicycle through the gates that lead to the PM’s office. The event was made public and christened “the Plebgate scandal” by the tabloid press.

The former chief whip vehemently denied the charges against him but the Metropolitan Police Service stood firm. Soon a campaign against Mitchell began, with The Sun newspaper publishing the leaked log of the event. According to Jones, the newspaper was getting revenge against the Tories after the phone-hacking scandal forced its owner to close The Sun’s sister newspaper, The News of the World, because of illegal journalistic practices. After four weeks of getting grilled on the front pages of newspapers, Mitchell turned into a “walking corpse.” As Jones describes it, the Plebgate event illustrated how even a very powerful man like Mitchell could be persecuted just because he was seen as a representative of policies that could do damage to the interests of the Establishment.

This notion of an all-powerful Establishment as source of all social ills that rules all facets of public life in Britain isn’t convincing. But the effects of neoliberalism Jones describes can’t be ignored either.

By this point we understand that the Establishment is a keyword of sorts for all that is evil in Britain. Jones looks at numerous examples, from the 1989 Hillsborough disaster that cost the lives of 96 football fans and was followed by a huge cover-up by the police and the media, to the parliamentary expenses scandal which showed the outrageously high amounts of money claimed by politicians from the public purse. He argues that the Establishment is at the heart of all those social ills and wonders how, despite the threat of these dark chapters to its discourse, it manages to be alive and well.

This notion of an all-powerful Establishment as source of all social ills that rules all facets of public life in Britain isn’t convincing. But the effects of neoliberalism Jones describes can’t be ignored either. His examples of the people whose lives have been affected by the neoliberal discourse are devastating. Just take the case of Brian McArdle, a “scrounger” whose weak and unproductive existence had run counter to the efficiency-centered ethos of the Establishment. With just one beautifully written paragraph about the sad case of McArdle, Jones succinctly shows the gap between the theory and practice of neoliberalism.

In the eyes of politicians who claim to have reformed the sickness benefits system through companies like Atos, McArdle’s was an unfortunate but by all means exceptional case. Jones’s depictions of McArdle’s plight and other similar cases are among the best parts of The Establishment. They most adequately support the book’s argument about the gap between the lofty ideals of neoliberalism and the damage it causes in real life. They exemplify, more convincingly than a conspiratorial notion of the Establishment, the failure of the powerful in society to protect the downtrodden and through that, more generally, the sad state of our neoliberal societies.

Kaya Genç is a novelist from Istanbul. He is curating a book on Istanbul for the American University in Cairo Press and working on his first English novel. He tweets @kayagenc and blogs at www.kayagenc.net.