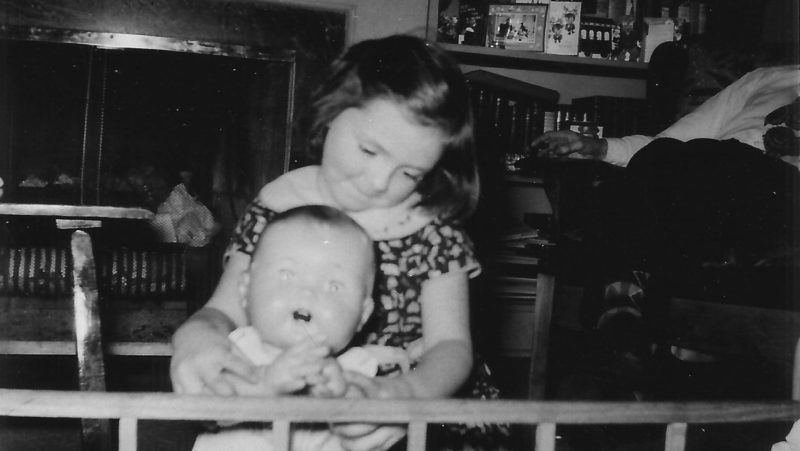

Every Christmas while she was still alive, my mother’s mother would leave a single unwrapped toy among the other presents under the tree for each of her children. My mother and her sister would always get a baby doll, their faces uncovered and waiting for the girls to scoop them into their arms. Denny was my mother’s favorite of these special Christmas treats. She carried him with her wherever she went, slept with him, whispered secrets into the plastic folds of his ears. When my grandmother died of multiple sclerosis—a disease that took her slowly, painfully; a disease that, because she was a woman in 1957, she was not even told she had—I believe Denny became a way for my mother to access her mother again. And during my grandmother’s funeral, which my mother and her siblings were not permitted to attend, I can imagine the two of them—Linda and Denny—holding each other. While my mother was away at graduate school, her stepmother donated Denny after wrongly assuming that my mother didn’t want to keep him.

“Oh…my baby…my baby.”

As a child I was convinced that I would be the one that would find Denny. I searched for him in every antique store and pawn shop in downtown Reno. As my mother danced her fingers over old trinkets and pins and jewelry, I would privately investigate the dolls sitting on dusty shelves or forever sleeping in bassinets. The dolls were pretty but old fashioned, with hard heads and stiff arms and the stuffing in their bellies gone clumpy. And anyway, the dolls weren’t for me. I was looking for Denny, and, when I found him, I imagined my mother would say, Oh, my daughter, you found him. Oh, my daughter, thank you. I knew that it was unlikely that Denny would have made it all the way from Portage la Prairie, Manitoba to Reno, Nevada. Then again, my mother had; it wasn’t impossible.

In the back of those antique stores, I would think about what I knew about Denny—he had a big head, his hair was part of his skull, he had tiny, pink painted lips—and when I found a doll that fit his description, I would present it to my mother, and wait for her to recognize him. She would put her hand to its face, cradle its full cheeks, and ask if I wanted it—she is so beautiful, Esther—and I would put it back because, this time, it wasn’t Denny.

I have been looking for Denny ever since. I think I have pinned down the store in which he was bought, the toy company that made him, the year he was manufactured. I have contacted a library in Wales that for whatever reason is home to catalogs of Canadian department stores to see if they have any information about the stocking of a particular store in Winnipeg. I have repeatedly interrogated my mother on what she remembers about him, tried to get her to describe him in a new way. Maybe there is a detail she forgot to tell me: stamped letters on his backside, a copyright date.

—Tell me again everything you remember about Denny.

—Well, he was big. Nearly the same size as me when I first got him. His body was soft.

—Stuffed?

—Yes.

—And his arms?

—His arms and legs were hard plastic, but his skin was sticky and velvet. Like real baby skin.

—Did he wet himself?

—No.

—Did his eyes close?

—Yes, they would flutter when he lay down to rest.

—Did he talk? Did he say anything when you squeezed him or pulled a cord?

—No, he didn’t talk. But he was a good listener.

I can’t seem to find him. I will get close, email my mother a picture, and she will say, No, no, that can’t be him. Denny had a much kinder face. It infuriates me that he can’t be found because I feel, however foolishly, that if Denny were found, something could change in my mother. Somehow holding her Denny in her arms might close up what has been left open and raw for so long. And perhaps she could whisper her secrets again into his waiting ears: That she wonders whether it is possible to mother well if you didn’t have a mother to parrot. That her heart is still broken. That every time she feels happy and proud and in love, it is accompanied with a sudden and deep grief for when it will end. Maybe having someone to tell might release her. And it feels like a sort of betrayal to admit this, but I also wonder if, maybe, my mom had someone else to tell, someone other than me, it might release me as well.

My favorite family photo album growing up was one from the early seventies: a brown leather album with vellum pages that clung to each other, pinning prints in their embrace. I was not in this album. There were plenty of albums of me looking chubby and pale, with a bowling-ball head. My first steps, my first recital, my birthdays, my birth—the graphic scene a horrible surprise between pages of photos of Christmas parties and Easter egg hunts from the early nineties. But this album, skinnier than the rest, rich chestnut brown, was the only album in our house of my father and his high school sweetheart’s daughter, my sister Camille. And, in the album, she grew. Age one, 1971, strapped to the back of our father, the smiling image of a man deeply in love. Age three, 1973, just before my sister and her white parents got kicked out of the public pool because their baby was “very brown.” Age four, 1974, holding hands with her mother, Nina, who had her hair permed and dyed black so she would look more like her daughter. But most of the album was from one day: age eight, 1978, a trip to the zoo with our father. In the pictures, Camille wears a yellow, long sleeve shirt, her name paraded across the front in velvet letters. Her hair is in pigtails. She looks happy and chubby and brown. I didn’t know my sister was Black until I first saw those photos. I suppose I knew that her forearms were darker than mine, but so were my father’s and so were my brother’s. And I knew that, when I had slumber parties at her house, that I would go home with matted, crusty hair because my thin strands slipped through the wide teeth of her comb and because, though she told me it would look bad on me, I secretly dipped my tiny fingers into the large tub of hair gel she kept on her sink and touched it to my roots. But my sister, twenty-one years older than me, was an adult. And all adults look different from all kids.

I remember looking at this album with Camille, enamored by seeing my older sister at my age. In every way I could think, I talked about her looks. How curly her hair was, how tan she looked. I told her that she was pretty and cute and chubby and looked so different as a kid. I told her so that she would bring up, on her own, what I was seeing—this new thing I was seeing, this new difference between my sister and me. But she said nothing.

I have never thought of Camille as my half-sister, though she is not my mother’s child. I have never thought of her as my adopted half-sister, though she is not my father’s biological child. Because to me, she has always only been my sister. And the differences in our blood, our looks, our experiences as women in this country is something that I, unlike Camille, have only ever had to consider in the privacy of our home, with sticky hair gel on my small, white fingers.

I have never and will never meet my sister’s mother. Something happened between them that I will never ask about, and to my knowledge, they have not spoken in many years. I will wait, patiently, until these secrets are offered to me—if they ever are. Likely, all I will ever know of Nina are the photos in that slim, leather album and the oblique comments from distant family members who assume I know the story: “Can you imagine not knowing your child?”

Around the time I first saw Camille’s photo album, my friend’s parents gave me a racist doll. It had wild hair and big red lips, and they told me it was rare, which I thought meant special. I displayed the small doll proudly on the dresser of the room I briefly shared with my adult sister. When Camille saw the doll, she told me that it wasn’t a nice doll. That one day I would understand. She didn’t tell me to put it away or not display it. She told me that having the doll didn’t mean that I wasn’t nice. I am sure that I cried.

That night, I put the doll in the drawer of a jewelry box that I had once loved. I never opened the drawer or the jewelry box again, but I always knew the doll was there—festering alone in the box on the top shelf of my bookcase, blanketed in shame. I don’t know why I didn’t throw it away. Perhaps because my friend’s family was rich and they had told me it was rare, and I thought that maybe it was worth money. Or perhaps because I just couldn’t bear to put a doll in the trash. Whatever the reason, I let the doll’s hidden presence haunt me until I moved away at eighteen. The doll was the embodiment of some monstrousness in me—my inability to throw this horrible thing away, my ignorance, this new gap of knowledge or experience between my sister and me. I don’t know what happened to that box with its secret. Though my family has sold that house and removed the furniture and repainted my oppressively pink room white, I can almost imagine that the doll is still there, collecting dust and building hate by the year.

I called my stepmother recently for her recipe for quibebe, a Brazilian squash and parsley mash. Presuming that I wanted to talk to my father, she answered the phone and immediately informed me that he was sleeping, couldn’t talk on the phone. It was a fair assumption; I rarely call to speak to her. Because we are not close like that. Because we are not close. Lately I have begun wondering if she wanted closeness—if, when she married my father when I was thirteen, she had imagined that we would eventually become friends. My father, a psychologist, had tried his best to associate his new girlfriend with good. Every time she was around, we played games or drove twenty minutes to my favorite ice cream shop. Jacque: ice cream. Jacque: ice cream. Jacque: ice cream. I ate so much ice cream that year.

In high school, one of my classmates told me unprompted that her mother thought my father was a bad man because he married a former graduate student. She told me that everyone knew—the faculty knew, the university knew, the students knew. I told her that I didn’t know what she was talking about. But, of course, I did; it was my stepmother’s youth—only a few years older than my sister—that I used to justify my rejection of her as another parent. She was strong and energetic and pretty. At the time, I doubted that she even noticed my disdain; I doubted she cared. I never considered for even a moment that maybe she had hoped our relationship would be something else—something tender, something like a mother and a daughter.

As my stepmother described to me how to make the quibebe, I noticed her Brazilian accent. Slight. A held-back quality to some of her words. An accent that I was too young and full of ice cream to hear in the beginning, and that I have only started to hear as I grow away from her.

May 5, 1967, a girl is born to a girl in Manitoba. The girls—the mother and the baby—are weak and cold and alone. A woman—Patty or Mary or Betty or Ruth—has driven down from her home up north to scoop her new baby into her arms. This has barely been arranged. Only a few months has the woman been on the list, but there are plenty of babies to spare. There are so many Jeans and Lindas and Susans here at this home for unwed mothers that the girls go by numbers: Jean #4, Linda #5, Susan #2.

My mother was Linda #5 from Portage la Prairie. Her British lineage gave her ruddy cheeks. Her dancer mother, graceful limbs. Her dentist father, strong teeth. Seventeen. Away at “an aunt’s,” left to ripen for nine months in privacy until she returned, empty.

Patty or Mary or Betty or Ruth paces in the waiting room, anticipating the moment the nurses will bring out the baby that will be hers. She hopes that the baby will be beautiful, but she knows that if it’s not—if the girl from Portage la Prairie, English-rosed and lithe and strong as she was, bedded a monster and those monstrous traits shadowed in the baby’s face—she would love it the same. Because she had waited for so long, and she wanted to do it well. To mother well. And she would. She would bring the child to her home, a house she owned with a husband in the north, and her child would never seek out the Portage la Prairie girl, Linda #5, my mother. They would live their lives happily without her.

When I submitted my DNA to track my ancestry, there was an option to track future health problems—genetic hints that I might suffer later. My father insisted I should: I am happy to pay the difference. It is important to be informed. But I didn’t want to be afraid of my body, of what horrible fate my genes might hold. I know that I probably shouldn’t have even submitted the DNA at all. I know there are concerns over security, that the genetic information given could be used—will be used—to raise insurance premiums, catch distant relatives if they commit a violent crime. It was a selfish act, and I am a selfish person. I like to look at the percentage Irish I am, the percentage Ashkenazi I am, the percentage English, German, French. Identities that I have never felt attached to. Identities that I have never identified with. But they are there, in my blood. Clear as day.

I get emails that let me know when updates have been made to my DNA map: new, more specific data; more relatives added. One day, I got an email that a new relative had been added. The ancestry company predicted, based on how much DNA we shared, that this new relative was my first cousin. His location was set in Manitoba. I have no cousins in Manitoba anymore.

For over thirty years, my mother, Linda #5 from Portage la Prairie, searched for the child that was taken from her at seventeen. It took over thirty years for my mother to finally hold her baby in her arms. And I just spit in a tube and found the baby’s son.

It only took a few clicks. Less than a minute of searching the Internet, and there was a photo of my mother’s daughter—my sister. She had let her hair go white, but it was still curly. Her eyes had the same squinted twinkle that I have only ever seen in one other person. Natalie looked much more like my mother than I did, which sickened me. I didn’t want to feel angry at her, but I did. Years ago, she made what I believed was a cruel, unforgivable decision. The way my mother described it to me then, though the details have faded, and I can’t bring myself to ask for them again, was: After a year of correspondence and a single reunion, Natalie was allowed to make a decision. Did she want to remain in touch with her biological mother, Linda #5 from Portage la Prairie? She said no. After that, I never for a moment thought that I would want to be in contact with her or her children again.

It would have been—still would be—so easy to message Natalie, or her son, or her daughter: my sister, my nephew, my niece. A few simple clicks. But I don’t know what exactly is allowed. And, also, I am afraid.

I saved the photo of my sister on my phone for only a few minutes before deleting it. Somehow, having it there felt like a betrayal of my mother and the family Natalie chose to let go.

There is only one photo of Natalie and me together. It is of my mother and her children in the brown leather booth of an anonymous restaurant where I met my oldest sister for the first and only time. I don’t remember anything outside the bounds of that photo. And I wonder now about so much. If I touched Natalie. If I shook her hand. If I was quiet—a child meeting a stranger—or loud—a child with her family. I wonder if I told her that I was excited to be an aunt, if I admitted that my friends at school already knew. I wonder if I sat next to her in the booth. I wonder if her husband came. I wonder if I noticed how much she looked like our mother. I wonder if she was jealous of me.

If I linger for too long here, I get upset that I can’t access it, that my memory, usually so meticulous and clear, could let slip this moment. But, of course, I had thought there would be another time. More time with my lost and found sister. And because I had thought there would be more dinners, I hadn’t known to remember this one. If only we could know when to pay attention.

Four years ago, my mother found an essay she had written in 1967. It was written in pencil and age had bleached the graphite almost entirely away. She transcribed it before it faded away completely and mailed the typed copy to me. It is hard to read my mother’s seventeen-year-old observations on the world because they are at once juvenile and impossibly, horribly mature. She writes about her roommates, her boyfriend, her loneliness, her fear. It is the last page that hurts me most, the only part of the essay about the birth of her daughter. It haunts me. I dream of this scene. It enters my fiction, and, more than that, it enters my life, in a way that could almost be confused with my own memories. And in the spaces between dream and reality, between writing and memory, I am unsure if this has happened to me or to my mother. And sometimes I am unsure if there is a difference.

I’m so, so cold and it seems so dark in here. Can it be dark? They keep coming in. Nuns. Cold and dark. They tell me to be quiet. They tell me I’m making too much noise. I am screaming. I’m supposed to “know” when to push. But I don’t know. I’m not doing this right. My body exploded apart.

“Oh…my baby…my baby.”

I feel like there are secrets that I could access if I wanted. If I asked for information, details to fill in the holes of this story, I believe it would be given. But I am afraid to ask. I am afraid that if I ask my stepmother if she imagined something else, she will say, Yes, who would have wanted this? I am afraid that if I ask Camille what happened with her mother, she will say, You can never understand. I am afraid that if I ask my mother about Natalie, whether my memories are correct and she was not allowed to even hold her child, if she knows the name of Patty or Mary or Betty or Ruth, it will open weeping in her that she doesn’t know how to stop. A weeping that I am too far away now to help stem. I am worried that, cathartic as it may be, it will mostly be painful. And she will text me in the night that she feels alone, that she is—objectively—alone. She will tell me that she has never felt understood. And I will not know what to say, so I will not say anything at all, but I will think, Yes, I know. Where did she think all of that sadness went? Whose blood does she think is filled with her saline? Who does she think I learned this all from?

I found out today that Denny was not given away. I had called my mother to ask when it had happened, a detail that I could safely fill, and she said, No, no you have forgotten. The story goes that my mother was visiting her father and stepmother when she found Denny in the basement, his composite face crumbling from age. She was on her way to Michigan for graduate school and had planned to come back for him. She would patch him up, display him proudly in her future home. The one who had heard all her secrets. She laid him down safe in a corner of the room and covered his body with a small blanket. Tucked him in nice. His eyes fluttered shut. She told him she would be back. And when she returned, months later, he was gone. My mother’s stepmother had thrown him away—cleaned the basement of the old things.

This knowledge is a rupture. A devastation. For as long as I can remember I have tried to reunite them, my mother and her baby. A way, perhaps, to right an impossible wrong. But I wonder if, by now, this hole in my mother is too scarred over to close. But maybe that too is a type of healing.

I so often wonder why we want to know the truth. Why do we yearn for answers when we know they will be painful? Is the knowledge that your child is safe worth the pain of losing her a second time? My mother would say yes, but as her daughter, I’m not certain. Before Natalie was found, I said I had two sisters. I liked the idea that there was one still out there—a friend that one day I would find. Then she was found, and then lost, and, soon after, I stopped referring to her. So much so that I often forget she exists at all. But if the pit left by Natalie’s absence has defined my life, so too have the rips and sutures of all my mothers and sisters. How can these wounds have arrived in me when there are still so many holes in my story? Can it be possible that it is the gaps and patches themselves that cleave us together?

I was at my sister Camille’s adoption hearing. I don’t know why she wasn’t adopted as a baby. I suspect that, at first, it was an oversight of two impossibly young parents, naïve and hopeful for a future in which legal rights wouldn’t matter. And after my father and Nina separated, slowly and painfully, legal access to their daughter likely had more to do with control. The court where Camille’s adoption hearing was held must have been the same family court where my parents got married, where my parents got divorced, where they separated their belongings and their time: painting here, its pair there; a week here, a week there. But I was kept from that, sheltered in the ignorance of youth.

I don’t remember much from my sister’s hearing. I don’t remember Camille, what she wore, if she looked happy or relieved or understood. I don’t remember my brothers, if they were both there—the new baby and one who lived abroad. I don’t remember my stepmother, young and still wary of me. I was home from college and had gotten a cavity filled an hour before, and mostly what I remember is slurring through my answers to the judge’s questions—questions to interrogate our motives, to confirm that my family were not con-artists, that my father adopting a forty-year-old woman was not a scam for insurance or wills, but simply a way to finally put things right. Mostly what I remember is half of my face slack from Novocaine and trying not to smile.

—Do you solemnly affirm that you will tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth so help you God?

—I do.

—Can you state your name?

—Esther.

—Can you tell me this woman’s name?

—Camille.

—Do you know this woman?

—Yes, she is my sister.

—Was this woman in your childhood?

—Yes, she is my sister.

When we were finished, the judge cried. This job can be awful, she said. Families torn apart, custody battles. But this, this you don’t see every day. And then she asked if she could take a picture of us, our family.