The story I usually tell is this: one afternoon about a year ago I met up with a friend (I’ll call her Olivia), someone I hadn’t seen since college. We were giddy and caffeinated, exchanging stories about the shocking realization that we were both dating—falling in love with—people we’d first been adamantly certain were just flings. Erykah Badu played as a soundtrack: “I was not looking for no love affair.”

Life is utterly unpredictable, cheekily magical in its tricks, we agreed. Once “cracked open” (what we’d come to call this perspectival shift, the recognition that you never truly know what’s to come), rationality only goes so far. Olivia mentioned that her fling-turned-boyfriend had found lucrative gigs writing copy through mass staffing websites like Elance and thought I might be interested. So I took his email and sent him a message that night, checking his profile on Facebook, as one does, out of curiosity.

The next day I found myself in between appointments at a coffee shop near Union Square. While sitting there, I remembered Olivia’s boyfriend, and looked down to find an email reply from him, sent within the minute. Strange, but not unlike the remarkable but familiar experience of thinking about someone just before they call. After skimming the email, I noticed that the man sitting next to me was texting with a woman named Olivia (the café had close seating and I am a nosy seat mate). When he got up to go to the bathroom, I pulled up Olivia’s boyfriend’s Facebook profile again. Indeed, this was the very man sitting next to me! (I should mention that he lives in Brooklyn, I in Harlem, and that this coffee shop is a place that neither of us had ever been to before.) When he sat back down, I tapped him on the shoulder. Incredulous, we talked about this improbable meeting, had a good laugh, and then went on about our lives.

The improbability of such acausal connectivity can feel like magic, or like a wish never explicitly made, but still come true.

To some, this strange meeting would be known as a “coincidence.” A crazy coincidence, perhaps. Some might even argue that it wasn’t entirely accidental: maybe I subconsciously noticed him before checking my email, which would explain why he was already in my thoughts (but then how did we both end up there?). Maybe Olivia had mentioned offhandedly that he would be in that area tomorrow, and I took in the information, again subconsciously, and organized my own schedule accordingly (never mind that my appointments had been made weeks prior).

To others—particularly those given to the spiritual-meets-pop psychology of Oprah and Deepak Chopra that has worked its way into the mainstream over the last several years—our chance meeting would be known as “synchronicity.” First coined by Swiss psychologist Carl Jung in the 1930s, and developed in his 1960 book Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle, the word describes a meaningful coincidence—the phenomenon where a thought is significantly, but not causally, connected to an event. In Synchronicity, Jung defines the title word as “the simultaneous occurrence of a psychic state with one or more external events which appear as meaningful parallels to the momentary subjective state—and, in certain cases, vice versa.”

Jung has his own illustrative story, one that he recounts in Synchronicity. It occurred during a session with a patient who was describing a recurring dream she’d been having about a golden scarab. Suddenly, a tapping on the window disturbed them, and Jung turned to discover “the nearest analogy to the golden scarab that one finds in our latitudes, a scarabaeid beetle, the common rose-chafer (Cetoaia urata).” The improbability of such acausal connectivity can feel like magic, or like a wish never explicitly made, but still come true.

Synchronicity isn’t verifiable through classical scientific methods, which can only test for phenomena that are reproducible, quantifiable, and, importantly, independent of the observer. Synchronicity, by definition, is dependent on the observer, since it’s only a subjective experience—the thought tied to the coincident event—that makes a synchronistic occurrence meaningful. (As a result, it’s not widely regarded as an actual theory.) Skeptics rationalize these happenings as mere coincidences, explainable as statistical chance or selective perception.

Rather than describing inexplicable miracles, Jung wanted to dismantle the magic and superstition surrounding the seemingly impossible, yet seemingly connected, events he and others had experienced.

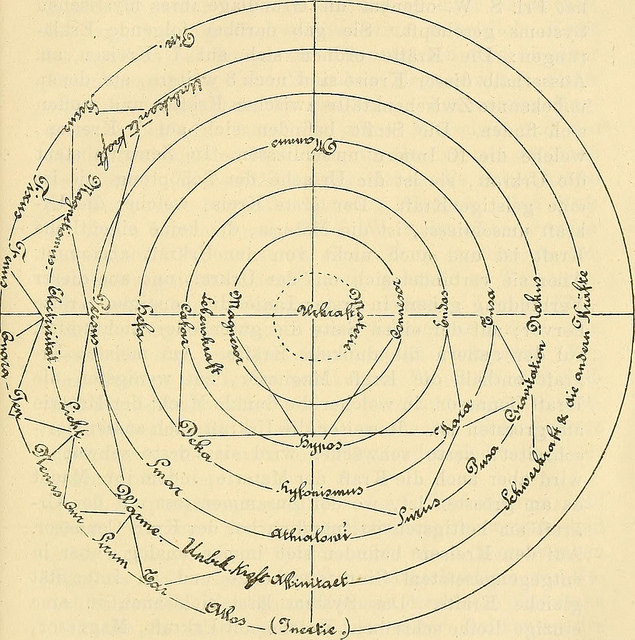

But Jung’s Synchronicity is meticulous in its data analysis, philosophical depth (pulling from the classical Chinese I Ching), and scientific inquiry. Jung was interested in studies of psychic processes and extrasensory perception, in astrology, and in the space-time continuum. Influenced by the “new physics” of the twentieth century—and his friendship with Albert Einstein, who was working on his theory of relativity—Jung wanted, he writes, to explore “a possible relativity of time as well as space, and their psychic conditionality.” He proposed synchronicity as a fourth principle in addition to space, time, and causality—as a phenomenon primarily concerned with “psychic conditions, that is to say with processes in the unconscious.”

Rather than describing inexplicable miracles, Jung wanted to dismantle the magic and superstition surrounding the seemingly impossible, yet seemingly connected, events he and others had experienced. He approached the topic with trepidation, wary of “plung[ing] into regions of human experience which are dark, dubious, and hedged about with prejudice,” yet passionate to share the conviction that had been building within him for decades: that while the causal principle can only account for some natural processes, a significant connection between thoughts and events need not be absent simply because cause and effect are.

“The so-called ‘scientific view of the world,’” writes Jung, “can hardly be anything more than a psychologically biased partial view which misses out all those by no means unimportant aspects that cannot be grasped statistically.” It follows, Jung argues, that the existence of one or more other factors is necessary to explain the world, with all its contingencies and its deep, if not entirely explicable, meaning.

It’s a human instinct to search for meaning in the universe—to see a pattern in all the chaos, pain, and nonsensicality. The tendency to look for interconnectedness and order also helps explain why we all feel blessed when we encounter synchronicity; its importance feels self-evident.

But following that sense of fortuitous blessing, rationality raises the inevitable question: What do these miraculous synchronicities mean? When I was confronted, just after thinking of him, with Olivia’s boyfriend’s email and then, amazingly, with him sitting there next to me, I wondered what it could all mean—this instant delivery of an all-too-eager Buddha I’d only half asked for. (Amusingly, his email contained a treatise of advice that far exceeded my original question, “How do you make enough money freelancing?”) I wrote back to him the next day, to say that it was nice to have met and what did it all mean?!, the latter mostly rhetorical, but open to an answer, if he had one. His response: “There’s no way to know in any objective sense so go ahead and ascribe whatever meaning helps you take whatever positive changes you want out of it all.” Clearly.

Ultimately the idea is to tune into an awareness of the magic happening around us all, all of the time, but it can feel like an edict, one that in some prescription negates wonder.

I was annoyed by what felt like a debunking of the miracle we’d witnessed, like an almost-grown child whose parents realize she knows Santa doesn’t exist, but patronizingly remind her of the fact anyway rather than playing along, explaining that it’s fundamentally her belief in Santa that truly matters and keeps her good year round, not the reality of the man himself. Leave the cookies out or don’t, dear, it’s all just what you make of it.

It’s true, of course. But an over-emphasis on personal agency can also deflate the concept, which is evident when Self-Help hijacks synchronicity. Secular-spiritual pop psych—urging us to “trust in the universe” and “find your flow”—sometimes identifies synchronicity as a demonstration of openness and alignment, of living with a possibility mindset. This can make experiencing synchronicity feel pretty good, like a pat on the back on top of the miraculous experience itself. Here’s a gift, and congratulations, its very existence confirms that you deserve it. When you’re noticing synchronicity in your life, people like Chopra will tell you, you’re on the right track.

Ultimately the idea is to tune into an awareness of the magic happening around us all, all of the time, but it can feel like an edict, one that in some prescription negates wonder. You’re supposed to open yourself to the possibilities of the universe but the final experience becomes solipsistic. It comes from within. Watch for signs, we’re told, and ascribe whatever meaning helps you make positive change (read: improvement).

It can be fun and effective to do so, like reading your horoscope—not because you necessarily believe it’s accurate, but because it’s an exercise in self-inquiry, in opening your mind to what lies just behind the conscious. “Wait before signing any contracts until Thursday, when Saturn is no longer in retrograde” may sound like an order founded on New Agey meaninglessness, but it can also help you face thoughts, events, and feelings that you haven’t grappled with—from a literal lease signing on the horizon, to an agreement you had with your mother not to bite your nails, to a big life change you’ve been mulling over (or avoiding), to deeply held beliefs and emotions about the very role contractual agreements have in various aspects of your life, in relationships, at work.

Synchronicities can bring about a similar process of self-examination, often about your connection to the world around you. But with an emphasis on the individual’s power, synchronicity tends to go the way of The Secret or its “law of attraction” precursor, The Power of Positive Thinking. These guides to “manifesting”—the idea that what you think will manifest itself in reality—can create a cult of belief that turns positive thinking into a moral issue, as if everything can be controlled by individual agency.

Jung’s belief that studying synchronicity might dismantle the mysticism around it seems to lose part of what’s so inspiring about his concept, what can make it seem like a contemporary, secular way of considering the divine.

The belief in manifestation—that the external will reflect the internal—is not Jung’s theory of synchronicity. But in some versions of popular spirituality, Jung’s concept has been taken to explain relationships between the internal (consciousness, will, hope) and the external (the surrounding world) in a way that puts undue emphasis on active individual consciousness. If you’re living in the right spirit—choose abundance by having faith! be detached, but don’t force it! open yourself to co-creation with the universe, but do it effortlessly!—good things will happen to you. Believe, trust, be open and receptive. But don’t try too hard.

It’s a very American state of mind—one that can quickly Horatio Alger its way into dreams of self-creation, starting with the mind (and often ending, in Self-Help’s most vulgar editions, with wealth). I’m all for positive thinking, but not at the expense of all sense of structural inequality, and not when it involves blaming the victim of institutionalized inequality, social prejudice, or even disease.

Jung’s synchronicity had very little to do with individual conscious effort (except in the supposition that the more you’re interested in synchronicities, the more you will probably notice them). An incidence of synchronicity is like a prayer in reverse: you haven’t asked for anything, but in its wake, you see the meaningful, if not completely understood, imprint of connection in the world (or, if you’re coming from a spiritual perspective, the mark of the divine).

This “acausal connecting principle” demonstrates an interrelatedness between everyone and everything—proof, to Jung and others, of the collective unconscious, and of a not-fully-understood connection between the material and our psyches. Recognizing the subjectivity of all observation, Jung writes, “not only help[ed] loosen physics from the iron grip of its materialistic world, but confirmed what I recognized intuitively: that matter and consciousness, far from operating independently of each other are, in fact, interconnected in an essential way, functioning as complementary aspects of a unified reality.”

There’s a kind of paradox to this. On the one hand, like a monotheistic God who acts completely independently of the human will—with the power to bless or curse you—synchronicity depends on its feeling irrational or inexplicable, depends on the feeling that it comes from without, from outside the self. Like a blessing, and truly unlike prayer, it couldn’t have happened if you tried to make it so.

And yet, it is our subjective rationality, our connective thinking and ingrained habit of meaning-making, that gives synchronicity its power. We understand a synchronous event because we see a connection between a thought (or dream) and something that happens from without (the scarab at the window, my serendipitous café encounter). It’s this relationship between the internal and external, between rationality and irrationality, objectivity and subjectivity, that is central to synchronicity.

Jung’s scarab anecdote ends with the patient’s breakthrough. Jung writes: “This experience punctured the desired hole in her rationalism and broke the ice of her intellectual resistance.” The scarab, an archetypal symbol for rebirth, Jung notes, created an interruption in the patient’s psyche by opening her to the possibility of a non-rational connection or understanding of the world.

“Meaningful coincidences are thinkable as pure chance. But the more they multiply and the greater and more exact the correspondence is, the more their probability sinks and their unthinkability increases, until they can no longer be regarded as pure chance but, for lack of a causal explanation, have to be thought of as meaningful arrangements,” Jung writes.

Perhaps these feelings of synchronicity are a contemporary, secular version of the divine—something that interrupts our normal intellectual resistance with the feeling of a force and connection beyond the self, and a kind of meaning beyond rationality. “As I have already said,” Jung continues, “their ‘inexplicability’ is not due to the fact that the cause is unknown, but to the fact that a cause is not even thinkable in intellectual terms.” In a way, Jung’s belief that studying synchronicity might dismantle the mysticism around it seems to lose part of what’s so inspiring about his concept, what can make it seem like a contemporary, secular way of considering the divine. A miraculous interruption to our fantasy of total control and complete understanding.