Makenna Goodman’s debut novel The Shame centers on Alma, a woman adrift in rural Vermont with a desperate longing for something beyond the child-rearing, homemaking, and isolation that comprise her existence. One evening, she makes a sudden decision to get in the car and leave, driving from central Vermont to Brooklyn. “I was free,” Alma reflects as she drives down the dark interstate. “Behind me in the back seat were two empty car seats. No one was asking me for a snack, no one’s nose needed to be wiped, no one demanded the same song be played at top volume over and over.” But as she drives, recent and long-standing regrets coalesce into a series of flashbacks. Through these glimpses into Alma’s past, Goodman reveals the claustrophobia of Alma’s days, her uncertainties about parenthood, and her desperate loneliness, until what Alma is running from—and toward—merge, and the stakes become clear.

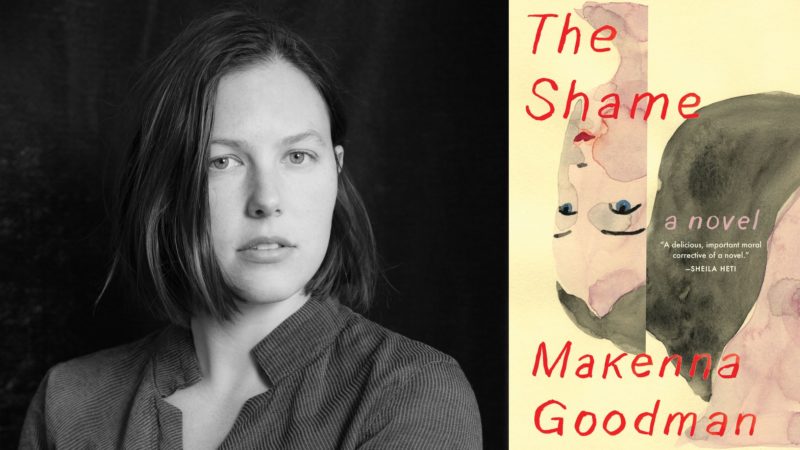

Goodman’s writing is lush and propulsive, creating a compact world like a fast-moving car in the night. The book joins a conversation about the near-impossible choices of motherhood explored by writers like Sheila Heti in Motherhood and Helen Phillips in The Need, and that Jenny Offill gives a jolt in all her work—most recently, Weather. What these writers have in common is not a focus on the “domestic,” a word that’s been used to damn women writers for a century, but on insistently complex characterization. Goodman’s work, like theirs, is not merely topical, but a landscape of the interior. Heti has called The Shame “a delicious, important moral corrective of a novel.” As in Heti’s work, here the material reality of Alma’s life is fodder for continual revelations about the traps of capitalism, motherhood, and meaning.

— Nathan Scott McNamara for Guernica

Guernica: Where did the story for The Shame begin? What was the first piece, and what was the process that followed?

Makenna Goodman: I wrote the first draft quickly about five years ago, after reading a book of psychoanalytic theory that likened the myth of Eros and Psyche to a woman’s journey towards self-awareness. The writer (a man) suggested that all characters in the myth were representations of a woman’s emotional life—that the myth was more about her own feminine and masculine projections than “men” and “women” and “love,” as is more commonly interpreted. I could see it was possible to be both Psyche (the naïve, mortal princess) and Eros (the God of Love who never shows his true identity), but what was Aphrodite (the Goddess of Love and Beauty) which represents such a force of power and desire? I realized: it was the internet, where we create and experience projections of ourselves in god or goddess form. And yet as I edited and added to the first draft, the novel became not just an inquiry into the ethics of the internet as a projection tool for the psyche, but [a story] about living on the land and what art is for.

Guernica: The Shame follows Alma, a rural Vermont woman who one evening makes an abrupt departure from her husband and young children to speed in her car through the night to Brooklyn. What’s your relationship toward driving? Did you pursue night-driving while writing this book to get Alma’s anxious and exhausted experience rendered clearly?

Goodman: I grew up in the Southwest until age eleven, when we moved to New York. But even then, we would fly into New Mexico for the summer and drive four hours through the desert until we reached our town, as my mother was too afraid to take a little plane. She used to play the same songs over and over to memorize the words; otherwise it was silent. Once I had my permit, I drove while she slept. Eventually, because of our dog, we began to drive the entire way from New York, and I spent a lot of time seeing the country from the car. (I remember specifically a tornado in South Dakota where we took shelter in the basement of a Super 8 motel.)

But driving at night, in terms of this book, is about traversing Alma’s unconscious. In dream interpretation, driving is said to represent a need for control, and the person driving in the dream is the one who has it. I wanted Alma to have at least an illusion of control, and also to have the front part of her mind focused on a mundane task while the other part could be set free to explore the deeper recesses. I didn’t drive at night for research, although I do almost all of my writing and reading at night—it’s the only time I feel is entirely for myself, when everyone is asleep, even the dog.

Guernica: Alma says, “On the edge of the woods, there is no meeting for drinks, there is no bistro on the corner, there are no mussels and no fries and no pinot noir. There is only the vista of voluptuous green humps, the lone glider overhead, the hawk being chased by the swallow, the walk to the mailbox, the drive to the market.” As a person who lives in Vermont, how are you finding a balance lately between remoteness and social connectedness, nature and cultural engagement?

Goodman: I’m practiced in isolation and, some might say, have been living on the verge of quarantine for over a decade. So isolation is not new for me, except that the context for it is completely different now. I’ve been going to some literary events online, for example, and I’m like, finally, I can go to these! And it’s a clarifying time if one can see past the horror for a second—so many of the bad systems that have been bad forever are being put on display. The reality is more and more clear: capitalism was founded on the enforced degradation of human lives, and we can’t hide from the truth! Many of us have known this already. But those in power are finally unable to turn away completely, because their ability to choose is also being threatened, and there’s this domino effect happening that is even affecting the rich (to a lesser degree, but still). And yet, while the possibilities for change are great, we are also on the precipice of full-on fascism. I guess you could say, while I consider myself lucky being comfortable in a state of isolation, the more I garden and the more I enjoy the fruits of my labor, the more I feel I am in hiding while the war is fought by someone else, someone braver than me, who likely has less.

Guernica: The Shame reckons with the pressure of achieving it all—happy children and a loving marriage, a vibrant social life and time and space for self-improvement, money and scruples. Motherhood, in particular, is described by Alma as a “backpack full of stones.” What is this backpack, and how does it relate to the state of being human?

Goodman: All people have a backpack in which we carry the weight of our childhoods, or ancestry, or variations of anguish. The weight of it depends on how we perceive its contents, as well as the means with which we have to lighten the load. Compared to most people, Alma’s problems are minor and maybe even laughable. But to her, they’re big and unwieldy and she has trouble carrying them.

I recently read Vigdis Hjorth’s Will and Testament, a phenomenal novel about siblings who, while dealing with the logistics of their inheritance, come to grips with the narrator’s story of being sexually abused by their father as a young child. This weight she has carried defines her life, but not her siblings’. In fact, all but one refuse to believe her, and she must prove her trauma is real in the face of their anger. But of course, there is no proof. She is a grown woman, Hjorth writes. The father is dead. What do they want, DNA? In the end, it is the narrator’s pain to deal with, and only hers, but by telling it to her siblings, she makes it alive in their minds. What we can do as readers is bear witness to a story, and perhaps in so doing can discover a version of our own pain and release some of its pressure. In my book, the journey Alma takes is about coming to terms with what’s really in her backpack. She thinks there are stones, but are there really gems? Is it dust?

Guernica: The long winters of Vermont in the book, as well as the mud season that follows, are conveyed as especially daunting. How do you find pleasure during these cold and dark stretches and how do your reading and writing habits evolve?

Goodman: It is around the middle of August that I start to look forward to winter. In August I think about all of my world that now has to be maintained, and I imagine it blanketed by a foot of snow. I think about the evenings that stretch on for hours, the way the fire will feel. I forget that I often feel suffocated by the relentless cold, the gray, the fact that my hands never warm up and are always swollen. Every winter is different, of course, and who knows what this one will bring. I read a lot and watch movies and stream shows in the winter, in bed with my husband. He rigged up this great table that attaches to the foot of our bed and we get the smart TV out of the closet. And we ski, sled, ice skate. I used to ski race as a child and have found joy in downhill skiing again with my children. We have these two small mountains near us that are basically community-run and not expensive or crowded, where the commerce of snow sports has not really reached. I find pleasure in the rope tow.

Guernica: Alma is a writer, and she struggles to complete a well-paid assignment for a children’s book because she feels it’s ethically dubious. How do you think about the balance between personal/private fulfillment and public/commercial success when you create?

Goodman: It would be dishonest to say that I don’t want my novels to be read by people and liked by people. All writers who publish are engaging in the business of ideas, and most artists (like most people) want to be liked. But I’m doubtful fulfillment goes well with art. Maybe in making it, but not in selling it. What is success, even? How is it defined? Money is one thing, ideas are another. If someone can make money from their ideas, they’re lucky. But the business of ideas needs innovation to propel it into new spaces, which means a certain amount of vulnerability and risk. As a reader, I seek books that push this edge, many of which go under the radar because they are seen as unsaleable by the commercial publishing machine. As a result, many of my favorite writers are not contemporary; some have been rediscovered recently, and many are just now being translated into English, only because they’ve achieved legitimized status in their country and are now deemed worthy of our attention.

As a writer, I create because I have a question that eats at me and it’s the only way I know how to answer it. I also write in conversation with writers I admire. And while I don’t think of “commercial success” as a dirty word, it’s best for me to see it as a by-product of art, not as the engine of it. In my book, the narrator wants to create something meaningful, but she doesn’t have a clear vision. The children’s book is a test—what is her bottom line? Where are her scruples? What is she really trying to say and is it worth it? And, also, what is so wrong with making things and getting paid for making them? She’s confused, she doesn’t know exactly.

Guernica: What were the primary influences on this novel?

Goodman: I always want to ask people this question and I know why—I want the secret. How did they do it? Why did they do it? What made them do it, who is to blame, who can we give credit? And can I prove to myself that I can do it too, or do it better? As if we could retrace our steps and then crack the codes of our unconscious. But if I told you one influence, I’d be covering up another. The only way I know how to answer this question is to say: through living. And reading.

Guernica: Alma says that she needs to buy rather than borrow the books she reads, to take up space in her house as proof she had consumed them. How do you feel about owning or borrowing books, and how do you decide to keep or get rid of books?

Goodman: I am a book hoarder and I spend a fair amount of money on books. I also spend a lot of time, usually in the winter, staring at my bookshelves. I will buy a book, shelve it, and years later discover it having no idea how it got there or why I was interested in it. But then, one day, I’ll need it and it will be right there waiting for me. I also love libraries, and I take my kids and borrow books. But I never get books from the library for myself. I need to underline my books, and I need them as references for the future. If I don’t like a book, however, and if there’s not a good reason to keep it, I will remove it. But usually not right then, because I have to be sure. Sometimes I give them away to people I think will appreciate them. One of my greatest joys is loaning books to people who ask me what they should read next. But I have lists of people I’ve loaned books to that I want back, and this is a message for them: I’m coming for you! Give me my books back!

Guernica: What have you read lately that’s changed something about the way you’re thinking?

Goodman: For a long time I believed that the truest thing I could do would be to focus on the elemental parts of living. I would know how to grow my own food and preserve it; I would raise my own animals and slaughter them myself; I would harvest fuel from my own land; etc. And for a while, I felt that I was moving in a direction away from excess and consumption, towards truth, I guess. But over time, especially after having children and enrolling them in public school, I saw how selfish I had been, and while yes, I was building topsoil and operating in an ethereally energetic space that produced ions of love, ultimately I wasn’t doing anything to help other people directly—at least not the people in my community—and I certainly wasn’t redistributing my wealth, even though I railed a lot against the oppressive systems from which I benefited daily. It seemed impossible to live close to my values without being authoritarian. And I see it all the time: the shame placed on people for not eating organic, the way progressive-minded people so often overlook the reality of being poor, that having a choice is a luxury.

I have been re-reading what is considered one of the more important agrarian bibles, The Good Life by Helen and Scott Nearing, which I read years ago when I moved to Vermont. I am noticing so many new things about it now. The first is their relentless binaries: this is good, this is bad, etc. The second is their fundamental rule for being able to live the good and simple life on the land, with time for merriment and culture when the labor is done. They write: any human with a “normal sense of vigor” can live this way. And for the first time, I saw what that really meant: That you had to already be wealthy. And while vigor, to them, meant something ethical and logistical—were you down for the cause, were you healthy—in reality, vigor is defined by a social system. I am thinking much differently about the agrarian movement in general these days and about what it means to live in a rural area, “away from it all.”