The summer I graduated from college my mother, Akiko, gave me a journal that she had started writing when I was born. It looks like a child’s notebook, a faded blue cover with yellow, green, and red designs, worn at the corners from use. The front is misleading with the word recipes printed in English and French, so when I first opened the book, I thought I’d find a record of her cooking. The entries are mostly in Spanish, the language she grew up speaking in Uruguay and Colombia. Each one begins: “Mi querida Sanaë.” Her tone is descriptive and confessional, and the emotions she kept hidden for so long flow openly in writing. Reading through the journal I discovered that she had stopped writing when I was six but didn’t start again until the spring before I finished college, more than fifteen years later. To make sense of the gap she wrote: “The diary ends here. What happened is that I could no longer write about my life. I was not well. It is very short but through reading it, you can have a little glimpse of me.”

I read the journal quickly and tucked it away as though it were a hot coal. That summer, when she gave me the journal, my mother and I did not get along. We were angry at each other and our family was splitting in half. How to take in the intimacy of her pain when I felt consumed by my own?

Throughout my adolescence I longed for her to notice me, to ask me questions. How are you, how was your day, how do you feel? I would hear other mothers say to their children, and I always felt a pang of hurt, the sense that she didn’t care or perhaps didn’t love me. That my existence bothered her. When I requested her attention, she told me I was spoiled. She repeated this so often that I believed it to be true. Perhaps I was spoiled beyond repair and it was selfish to ask for more.

On weekdays, I would wake to the sound of pots and pans clanging in the kitchen as she prepared my school lunch: fried rice with vegetables and scrambled egg; unwieldy sandwiches filled with tempeh, shredded carrot, and pickled cucumbers; spaghetti with homemade tomato sauce. I would eat the leftovers for breakfast, or a steamed bun dipped in soy sauce and olive oil. She fed me nutritious meals three times a day, but I still felt starved for her affection. Dinner was a silent affair with my teenage brother shoveling food into his mouth and disappearing behind a closed door. I absorbed my mother’s cold shoulder, her hostility, and assumed it was my fault. I assumed it was my presence that made her sullen. It didn’t occur to me that her bitterness might be directed at my father and his mysterious absences, her isolation as a Japanese woman living first in Paris and then Melbourne, so far from Japan and Argentina. After twenty years in Buenos Aires, she had uprooted her life and moved to France with her eight-year-old son to be with my father. Seven years later, we followed him to Australia for his work.

As soon as guests came over, however, her face brightened. She was surrounded by friends from her work as an Alexander Technique teacher, her macrobiotic community, and the health retreats she dragged me to several times a year. I would hear her name spoken aloud with obvious warmth, though it was often mispronounced, the Japanese vowels difficult for an English ear: A-ki-ko. (In Uruguay her teacher had renamed her Clara.) Our neighbors often invited us to Shabbat on Fridays, and in those instances, I’d catch glimpses of this other woman: cheerful and generous, someone who loved to tell stories. ¡Qué horror! she’d exclaim, unafraid to jump into the heat of a conversation. My father liked to say that he could seat her next to anyone at a dinner, because he trusted her to find common ground with even the dullest person. Outside of motherhood, she seemed to flourish, whereas at home, she folded into another self. I knew something was terribly askew, the energy pulling us in opposite directions. The farther she drifted from me, the more I feared losing her.

What if you die? I would ask. She was ten years older than my father and forty-four when I was born. Death is natural, she’d reply, I could die tomorrow. I hope I won’t live to be too old. And what is too old? I’d ask. Eighty, she’d say. To me, her words were proof that I couldn’t rely on her presence, and perhaps she wouldn’t mind if I also disappeared from her life.

Akiko had studied educational psychology, and in raising my brother and me, she had steadfast theories about a mother’s relationship with their child. She prided herself in upholding her definition of what a mother should be, someone who doesn’t share everything with her daughter, someone who doesn’t shower her with compliments—an act of protection but also isolation. She wanted to create a clear separation between mother and child. Her role was not to tell me how wonderful I was. For her, it was important to create a distinction between being a parent and a friend. Sometimes I searched for memories of her congratulating me, signs that I was good, moments of shared celebration. It doesn’t mean that she never said bravo! but that I couldn’t remember her cheering me on felt indicative of her indifference.

In The Cost of Living, Deborah Levy writes ambivalently of the mother figure: “…we blame her for everything because she is near by. At the same time, we try not to collude with myths about her character and purpose in life. All the same, we need her to feel anxiety on our behalf—after all, our everyday living is full of anxiety. If we do not disclose our feelings to her, we mysteriously expect her to understand them anyway…. When our father does the things he needs to do in the world, we understand it is his due. If our mother does the things she needs to do in the world, we feel she has abandoned us. It is a miracle she survives our mixed messages, written in society’s most poisoned ink. It is enough to drive her mad.”

Perhaps this is what my mother was trying to convey when she told me I was spoiled: Why should she be asking me about my day? Who was looking out for her? No matter. Reading Levy’s words, I better understand why I never thought to question my father’s long absences. He was the provider in the traditional sense, the parent who traveled for work and therefore was greatly missed. I waited for his return, counting down the days with fervent anticipation, whereas my mother’s presence went unnoticed—as constant and invisible as the air we breathed.

As a child, I thought I was the origin of everything. Her palpable unhappiness spread in our household like black mold, the bursts of uncontrolled anger that made me run and hide from her. At times she pulled my ears so hard my nose bled from the shock. Children are difficult, they press buttons, learning what these are over time, provoking and driving their parents mad. But the guilt I felt was enormous. I didn’t know how to make sense of it. And so, even as I blamed myself for her misery, I ferociously blamed her for my own unhappiness.

The winter before my mother gave me her journal, before my parents began divorce proceedings, my father told her that he’d been secretly seeing another woman for several years. My mother and I rarely spoke on the phone throughout college, but in the spring before graduation she called me several times, weeping, unable to say what was causing her such sorrow. She had been cold to my father for years and I assumed she wanted this divorce. I’d never seen her cry and was irritated by her sudden tears. In June, she left France to stay with my brother and his family in Washington DC while I returned to Paris after graduation to live with my father, who had rented a small apartment.

A few days later, he told me about his affair along with an additional truth—they had a son and were expecting their second.

My mother knew about the affair, but not the children he’d fathered. He asked me to keep his secret from everyone, especially my mother who had fallen into a deep depression. She was too fragile, she must be protected, my father said. Let’s wait a year; one piece of news at a time. I’d often felt closer to him, and hadn’t he chosen to confide in me? He showed me photos of the woman who would become his wife and my half-brother. I agreed to say nothing.

The following morning, I woke with the sense that I no longer knew my father. I waited impatiently for the anger of his betrayal to replace the pain blooming in my chest. He had always been elsewhere, never entirely at home with our family. Though she knew nothing about my father’s other children, my mother had known about the other woman for months and had withheld it from me, making it difficult for me to console her. Another one of her barriers, even though I was an adult. I understood her sadness, and yet I blamed her for shutting me out.

My father went away for most of the summer to visit his other family in Thailand. I retreated into a fortress of silence. I floated around his apartment, overcome by a sense of loss I couldn’t articulate or place. Our old furniture barely fit in the small space. The table took up most of the narrow kitchen and boxes of books and toiletries sat in the living room, waiting to be unpacked. My mother’s presence was everywhere. I recognized her bowls and pans, the long wood chopsticks she used for cooking, dried seaweed in a glass container. She practices non-attachment and had moved to the US with few belongings from her past life, whereas my father, a natural hoarder, had kept it all, even a jar of salt with her distinctive handwriting on the label.

I waited for an apology from my father that would never come. And for a few weeks I kept the secret of my half-siblings from the one person I longed to be mothered by.

In August, I moved to New York and visited my mother in DC for a weekend. My brother, his wife, and their son had left to visit family in Maine. Their house was undergoing renovations, so we both slept on a pullout couch in a spare room. We spoke about my father’s affair with a woman who was thirty years younger, how he’d kept the relationship a secret from us for so long. My mother was a private person and never spoke about their marriage, but now she candidly described her feelings of abandonment and heartbreak. They had shared countless meals, she had washed his clothes, and she hadn’t suspected it.

She cried all night, her body curled and shaking, while I burned with my father’s other secret. I thought about how much she had changed since my childhood, from a looming and loud presence to this frail woman, smaller than me, sobbing through the night. In the morning she held my hands and told me about her thoughts of dying. My father’s words haunted me: she’s too fragile.

We walked to the bus stop hours before its departure. She wanted to have breakfast at a bakery she’d discovered, a place called Panera Bread. Neither one of us knew it was a chain. We were among the first customers on that Sunday morning. We sat at an outdoor table close to Dupont Circle, eating our toasted sandwiches as we waited for the bus to arrive. Why didn’t I speak to her then? Why not say that my father had a son and was expecting another? I stepped onto the bus and waved goodbye from the window.

When she finally found out a few weeks later, she accused me of betraying her. Her accusation stayed with me for years. Later, I interpreted its meaning: I should have chosen her. Perhaps I’d have had the courage to tell her the truth, if only I could’ve seen all the ways she was strong: single parenting my older brother while she attended graduate school in her late thirties, breaking ties with her Japanese family, building communities in new countries, becoming fluent in four languages, changing professions overnight, raising me almost on her own.

In January, I returned to the journal. Nine years had gone by since I’d first opened it. By then I had finished writing a novel, inspired by my father’s hidden family and centered on a fraught and intensely loving mother-daughter relationship. My mother and I had grown close, a slow process of healing that took several years before we could be in the same room without yelling at each other. She told me about my father’s infidelities and the severity of her depressions. She encouraged me to maintain a relationship with him because despite everything he loved me and had been a good father. Today she is seventy-four and I think of all the things we haven’t told each other, all the years we barely spoke until my early twenties. We are racing to make up for lost time.

One morning, earlier this year, I remembered her journal and pulled it out from my drawer, thinking I might peruse an entry here and there. After all, I had already read it, what was there to discover? Two hours later I sat at my desk pouring over the contents, a tightness in my chest as I willed myself not to cry.

I found a list of all the trips we took to visit family and close friends—Japan, Argentina, Brittany in France, and then our longer stay of eight years in Australia. Recipes from her macrobiotic years of food she prepared for me: millet, rice cream, steamed kabocha squash. Lengthy descriptions of my sleeping patterns as a baby. The journal entries are punctuated by constant mentions of breastfeeding and its nutritious benefits—she was a member of the Leche League and nursed me until I was two. “If only you knew how mother’s milk protects you from many things,” she writes. She lingers on the importance of creating a bond between mother and child during the “attachment” period, and how all future relationships are based on this bonding period. It gives a person their internal balance, she writes, and provides inner security and independence.

She describes the early days of motherhood, the constant exhaustion, the bliss of holding me against her chest. She writes bravo with exclamation marks whenever I’ve hit a small milestone, such as eating solid foods, growing bigger, or learning to crawl. I can see the darkness creeping through, those sections where her handwriting becomes rushed and uneven, when she mentions the resentment she feels towards my father, that perhaps she should have spoken up, and the deep feeling of abandonment from her childhood, a mother who neglected her. When she writes about her sister, she slips into English. “We were so unhappy… Not on the surface, but at the bottom of our hearts. I wonder whether war had something to do with it. The aftermath of war is full of hardship. My parents had lost almost everything.” (She was born in Japan in September 1945.) She refers to a “very big depression” during the summer before I turned two. “Living in Paris hasn’t been at all easy,” she writes. She is far from her family and friends. Sometimes she says that she’s feeling better, she’s made progress and her internal life is being repaired, little by little. And in those moments my heart breaks knowing what is to come.

I’m thirty now and starting to think about becoming a mother one day, though the thought terrifies me because of how I might replicate the patterns of my childhood. However, as I reread the journal, I discovered my mother in ways I couldn’t remember.

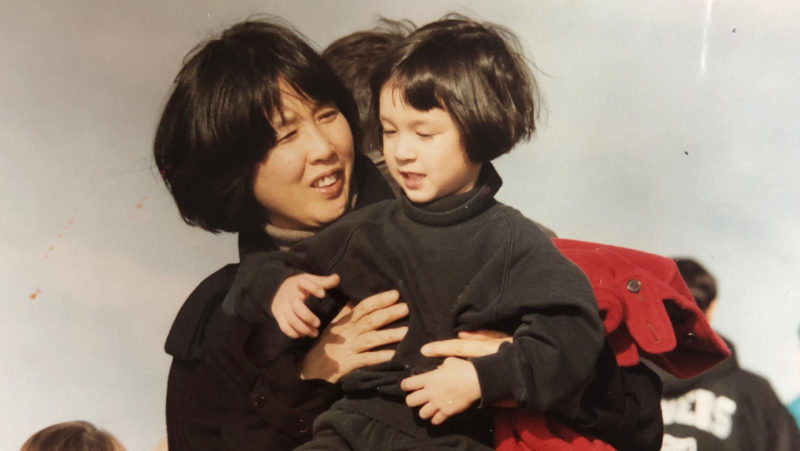

In one entry, when I was six months old, she describes leaving me with a babysitter while she goes to the doctor. When she walked through the door, I started crying. She took me in her arms and my tears turned into cries of alegría. “I also became very happy, beba!” she writes. “Sanaë, you have received so many kisses!”

Although I’d been too young to remember those moments, it was obvious that we had made each other happy, that we had comforted each other, and although I was shaped by her sadness, I had also taken in her joy. It must have been there all along, lodged within me, radiating warmth throughout the years, teaching me how to soothe myself in the most difficult moments. It made me less afraid to become a mother one day, knowing that our relationship wasn’t defined by her depression but the possibility that I had also inherited her light.

I halted at one of her last entries from April 2011, a few months after my father told her about his affair and before I found out. My parents had sold their house and she was temporarily living with a friend in the outskirts of Paris. She mentions finding a letter I gave her after one of our violent arguments. “My eyes filled with tears reading your letter,” she says. She acknowledges that I must have suffered from the continuous fighting with my father, and she regrets not knowing how to better care for their marriage.

How had I forgotten these lines? I’d read them almost a decade before and yet couldn’t recall seeing them. Perhaps the thick carapace I’d built throughout my childhood prevented me from capturing their meaning at the time. Now, at last, there was an opening, a space for her within me. I thought I’d been waiting for my father’s apology, but it was my mother’s love I yearned for. I absorbed it, entirely.