Miscellaneous Files is a series of virtual studio visits that uses writers’ digital artifacts to understand their practice. Conceived by Mary Wang, each interview provides an intimate look into the artistic process.

When I asked Olivia Laing to send me screenshots as part of this interview, she told me she only started using her iPhone a few weeks before. She’d primarily relied on “old-school” methods like notebooks and travel itineraries for her nonfiction books, three thorough and moving meditations on place, art, and the weight of our inner lives. For To The River, she walked along the Ouse, a river that attracts those who have “lost faith” and the one in which Virginia Woolf drowned herself. The Trip to Echo Spring involved a cross-country journey through America, on which she explored alcoholism through six writers who struggled to put down the bottle. In Lonely City, Laing used the work of four artists, including Andy Warhol and David Wojnarowicz, to examine the loneliness that plagued her in New York and seemed to have laid its grip on society at large. In between, she played hours of Tetris at a time—a game she later realized was an exercise in “how to assemble objects in empty space.”

Laing’s methods changed when she, somewhat unintentionally, started writing a novel in the summer of 2017. It was a moment when our political reality became stranger than fiction, and one in which Laing found it no longer possible to stick to the stable point of view she’d employed before. Written in seven weeks—and incorporating tweets from that time—Crudo follows its protagonist, a character based on both experimental novelist Kathy Acker and Laing herself, as she tries to make sense of the relentless news cycle. Laing admits to finding comfort in the “secretarial” parts of the work, and she sent me screenshots of her obsessively organized research folders as well as the presidential tweets that anchor Crudo. I met up with her at the Standard hotel in the East Village, the neighborhood that housed the ’70s punk scene Acker emerged from and one whose own certitude, following brutal gentrification, has become fuzzy.

—Mary Wang for Guernica

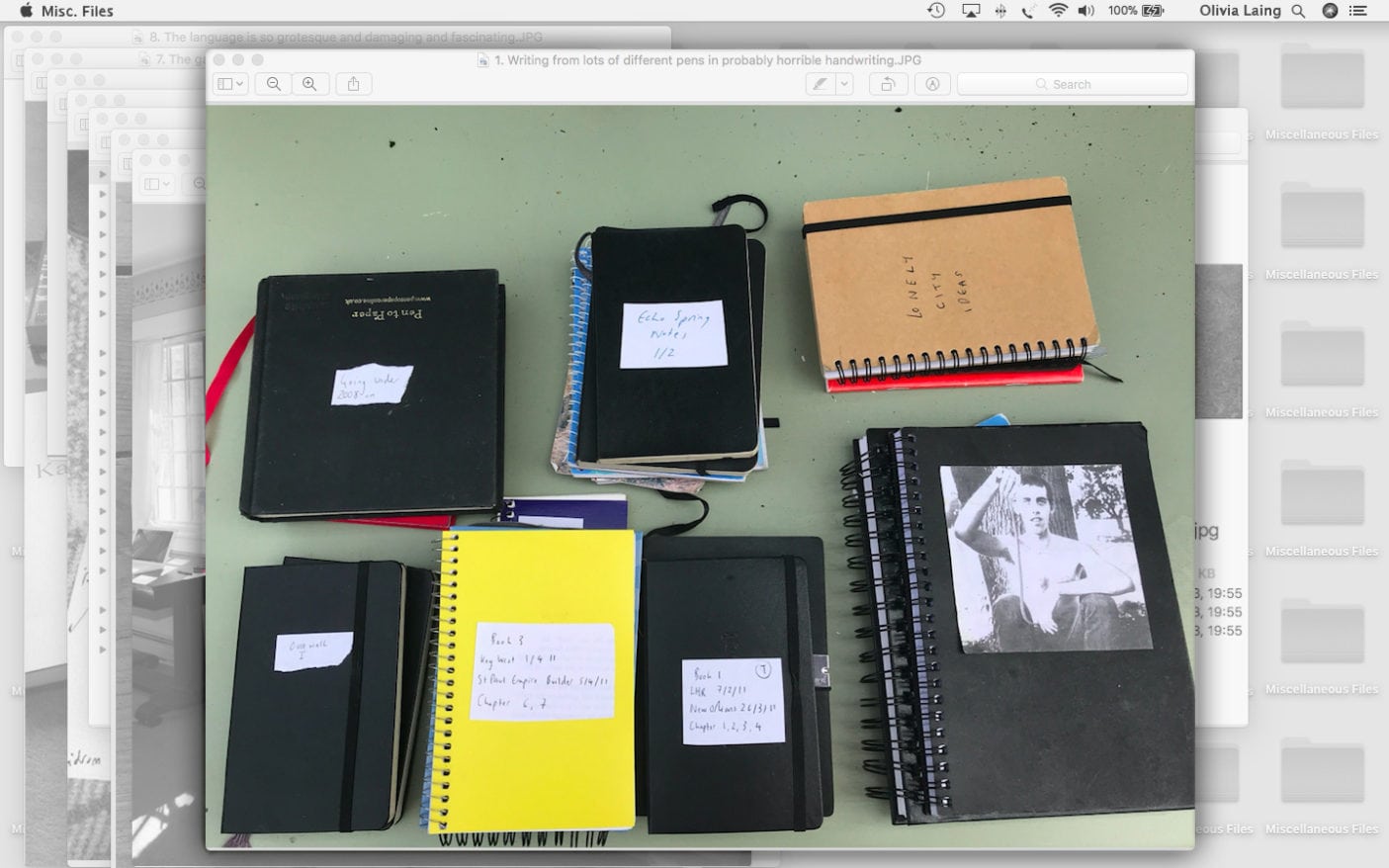

1. “Writing from lots of different pens in probably horrible handwriting”

Mary Wang: What do we see here?

Olivia Laing: This is a set of travel and archive notebooks. My first two nonfiction books are journeys that I transcribed and used as a skeleton for the project, on top of which I overlaid everything else.

Mary Wang: You have a strong attachment to place in your work, which is used as both a condition and a literary device.

Olivia Laing: I use place as if I’m making a visual documentary, where you might use shots of a lit-up building at night while telling a story, so as to juxtapose and heighten moods and emotional energy. In Echo Spring, for example, the most desolate stories are set on the coast of Florida, where things get lost in storms.

Mary Wang: It’s a cinematic technique, introducing movement and time to the static medium of writing.

Olivia Laing: I’m using the first person as a camera to track around. The control it allows me is really useful: I can be in an archive and zoom in to a particular object or pull out of it, and I can use it to calibrate the emotional mood quite closely.

Mary Wang: What do these notebooks look like from the inside?

Olivia Laing: The ones for To The River and Echo Spring are very dense, since they’re travel diaries. There’s writing from lots of different pens in probably horrible handwriting. The Lonely City notebooks are much scrappier, with transcriptions, phone numbers, things I was thinking, and a long list of archive notes. My background is in journalism, so I’m very disciplined about writing down everything I see. I’ve learned that just because you’ve seen something intensely doesn’t mean you will remember it a year later—I came to be so grateful for the times I’ve written down the color of the carpet in a room.

The Lonely City notebooks are messy but were truly crucial, as I was living in between England and the US while writing it, so I was often three thousand miles away from the archive I was describing. So I couldn’t pop back and go, What do the chairs look like? But I don’t use notebooks nearly as much as I used to. I’m much more inclined now to write things in drafts of emails.

Mary Wang: Notes are about convenience, so the forms most close to our daily lives work best for note-taking.

Olivia Laing: It’s not as visually exciting, but it has a notebook feel because it’s provisional. If you’re checking emails and you’re struck by a thought, somehow the draft folder feels like a natural place to store it.

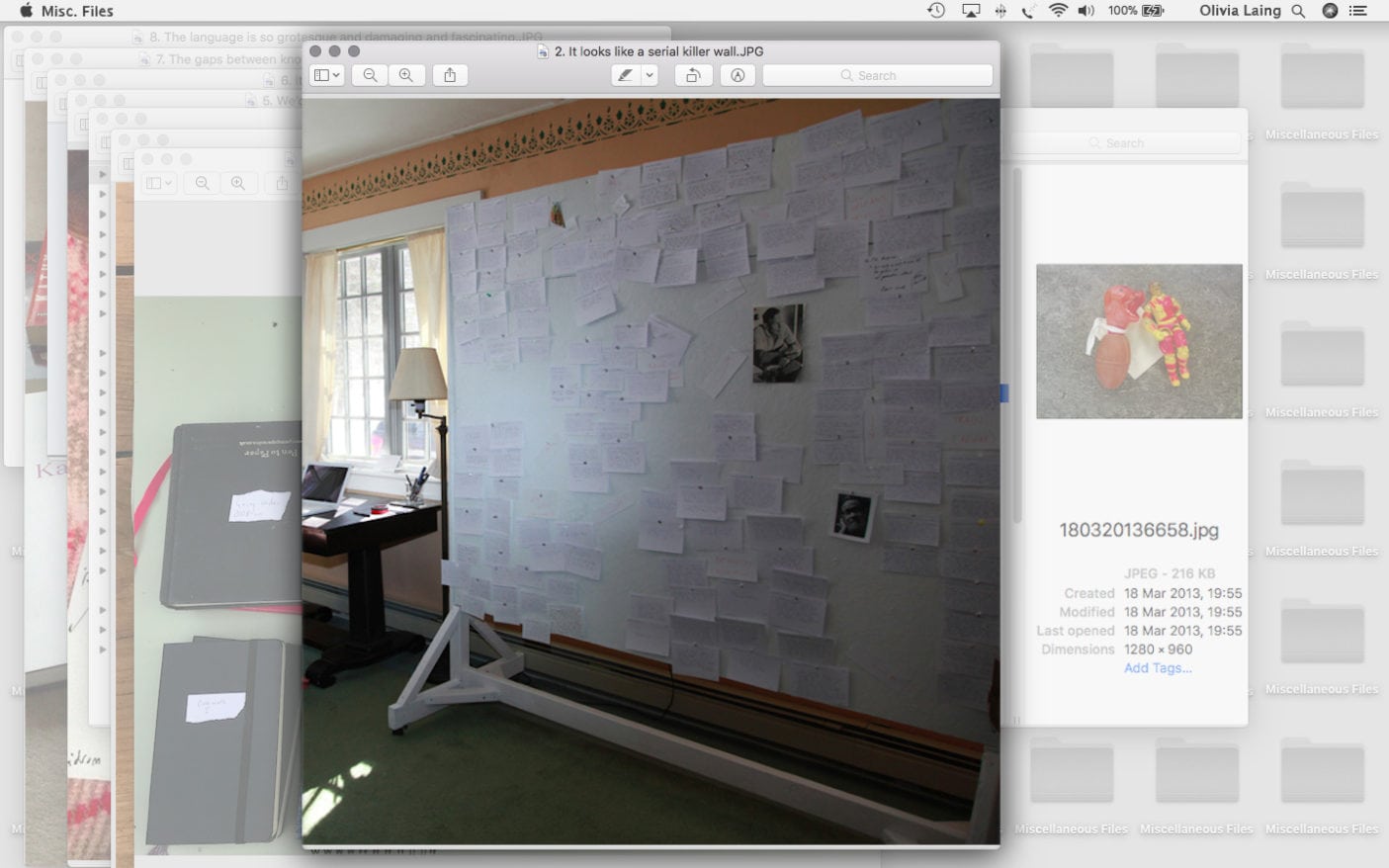

2. “It looks like a serial-killer wall”

Mary Wang: Where in your process was this?

Olivia Laing: This is before I even started the journey for Echo Spring—it looks like a serial- killer wall. I was trying to work out what would happen where, structuring the journey around significant moments in the lives of the authors. The journey was a way of staging and grounding much more abstract thinking about addiction and its causes. I plotted these sequences very carefully, then I’d book these elaborate trips and see what happened on the road. In the beginning, as a writer, you’re much more nervous, so you try to plan for everything, whereas later on you learn that you can improvise.

Mary Wang: You said that the idea for Echo Spring had been with you for a while already. It’s closely related to your own childhood growing up among alcoholism.

Olivia Laing: I wanted to include my personal story to explain the intensity of my interest. It’s the engine of the book, though it is dealt with in a very spare way. It was very painful to write. My mother is gay and her partner was an alcoholic, whom we ended up running away from. They got closer later on after she had gone through recovery, so I had an experience of both alcoholism and sobriety.

It’s a book about people who fabricate both for emotional reasons and for a living—lying is a deep part of the alcoholic persona. I felt like those truth-fractures were an artefact of being an alcoholic, but when I talked to my mother and sister for the book, I realized that our memories and narratives were all different. The alcoholic has gaps in their memory because they black out, but the traumatized mind doesn’t always remember either. There isn’t a single story. That was unexpected and disturbing on a personal level, though really it’s a revelation that informs the whole book, and maybe all my books: that there is no one truth.

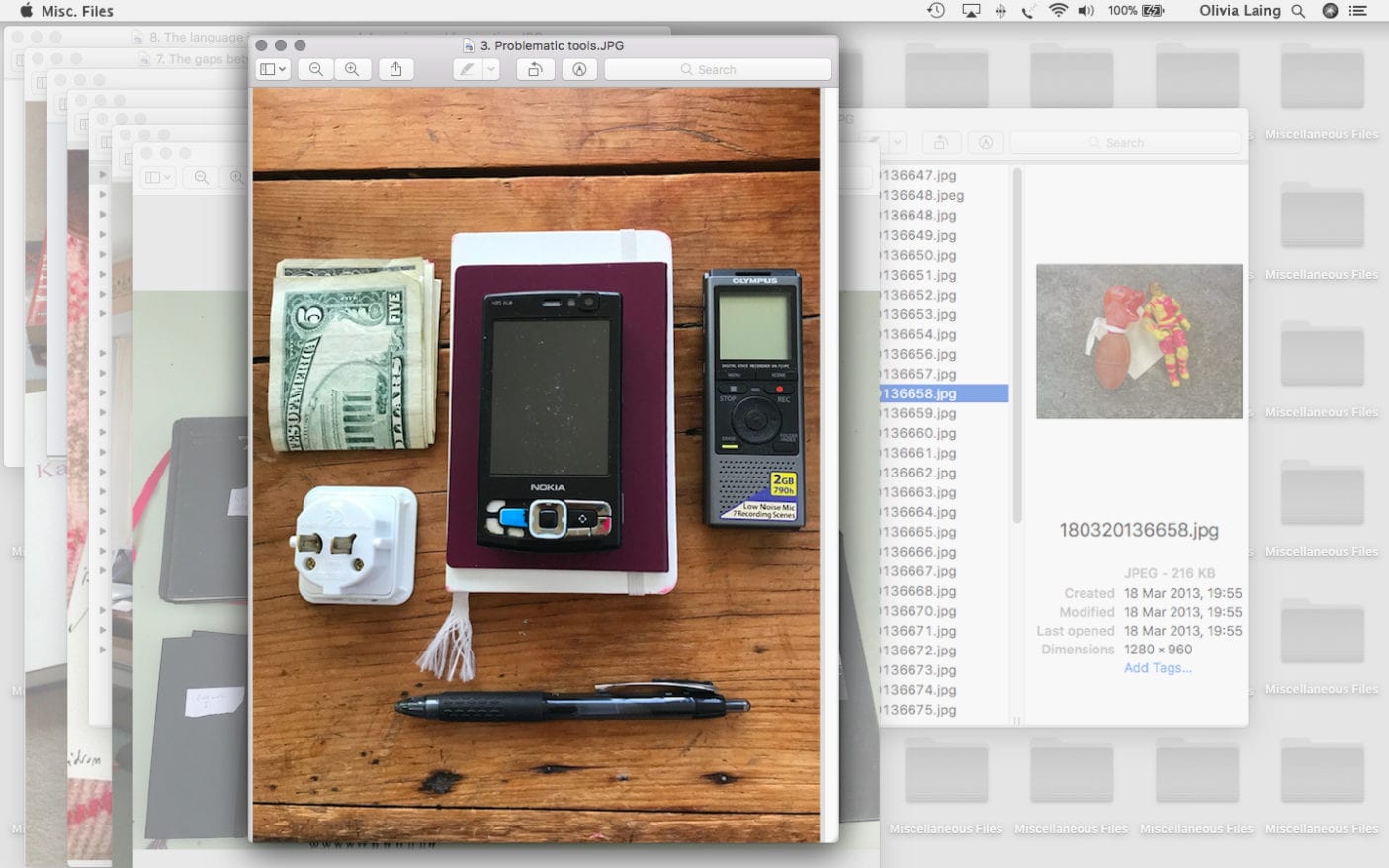

3. “Problematic tools”

Mary Wang: What do we see here?

Olivia Laing: This was the kit I used to take everywhere—my Nokia, my passport, my tape recorder, my pen, my travel plug, and dollars. The phone was a laughing stock with my friends for nearly a decade. I used it to take photos in archives, photographing the contents of every single folder of every single box. But both the phone and the tape recorder were problematic tools, because they didn’t always work. So there was a great note of terror to everything I did, especially when I’d flown hundreds of miles to see an archive for three days. When that happened, I’d just have to take very dense notes, which was frustrating because when it comes to archival work, nothing is as reliable as a photo.

Mary Wang: But there must be a reason why you held onto them for so long?

Olivia Laing: I didn’t want to have the Internet with me or have email arriving when I was working or writing. I’ve finally accepted that this isn’t really possible anymore. But my phone frees me up from my computer now, so I can write more easily on it. It’s an attention trade-off.

Mary Wang: How else do you prepare for the start of a research trip?

Olivia Laing: First I map out the journey, so there’s a lot of booking tickets and trips. Then I make appointments with different archives, which can take months. They’ve always said yes in the end, but it can be quite a process of persuasion. Then I do lots of archival trips, where I spend a week in a random place, live in a hotel, and document feverishly by day and write up my notes to the accompaniment of a room-service beer in the evenings.

Mary Wang: It speaks to how, for writers, so much of the work is not about writing. It’s the same for artists. A big part of the practice is managerial and logistical.

Olivia Laing: The logistics are a huge part of it. I’ll have the idea, but then I’ll have to plan where I need to be when and what information I have to acquire there. Then I’ll have to find the place where I’m going to do my writing, usually a public library where I can get whatever books and papers I need, and where I can’t be on Twitter that much. The logistics are actually a good respite from writing. It’s productive, and it can’t go wrong in the same sort of disastrous and agonizing ways.

There’s so much time that I initially thought was wasted, but I’ve learned over the years that’s actually where ideas are taking shape, invisibly. While I’m doing those secretarial tasks, the book begins to secretly take form. When I was writing Lonely City, I obsessively played Tetris for hours a day. I thought it was ridiculous, but it turned out to be an exercise in structure, in how to assemble objects in empty space.

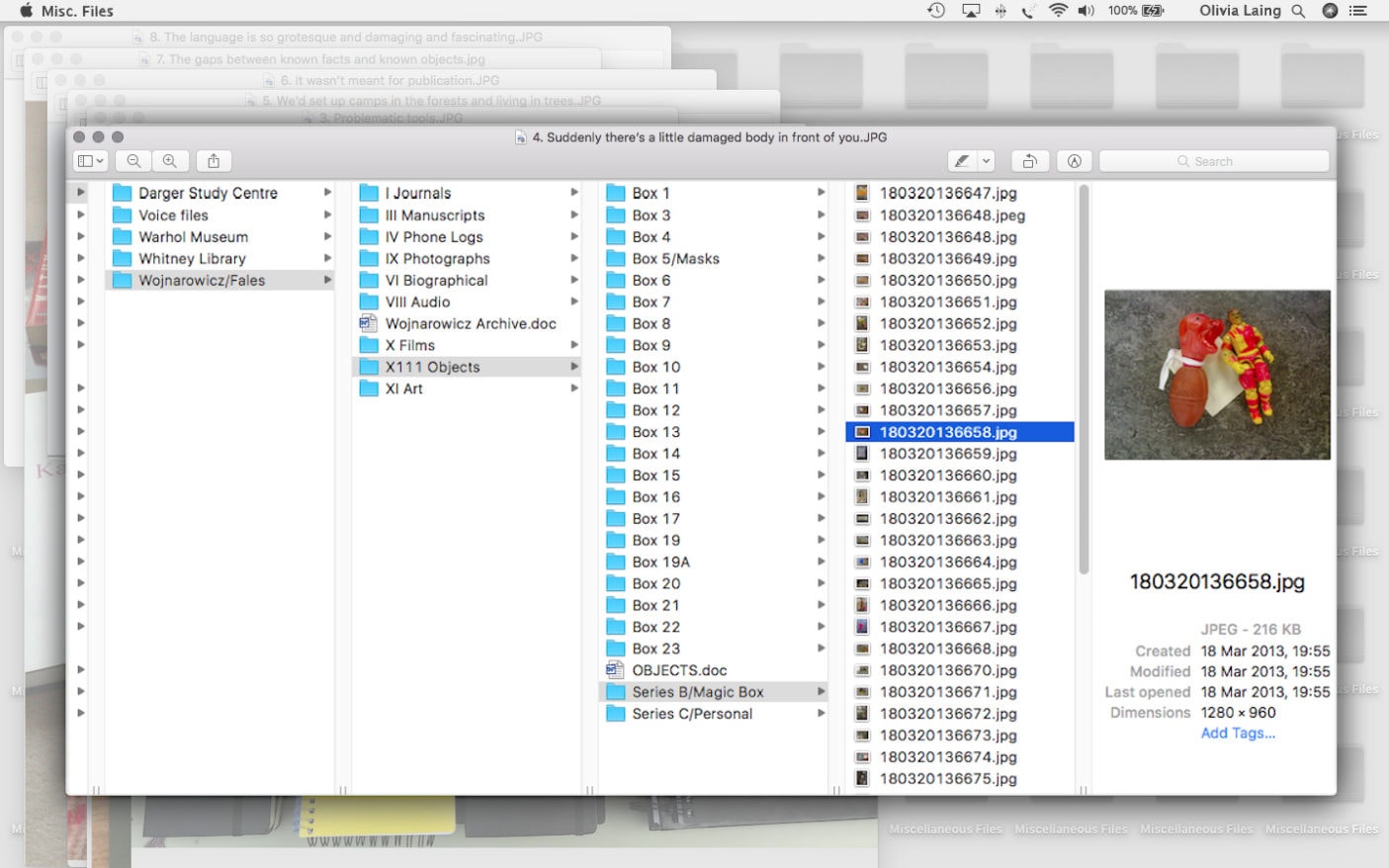

4. “Suddenly there’s a little damaged body in front of you”

Mary Wang: What’s this?

Olivia Laing: This image is of a plastic dog head and, I think, a monstrous space-man. David Wojnarowicz collected all these little toys, and they’d often crop up inside his paintings. When I was working in the Wojnarowicz archive at Fales I felt compelled to photograph every single one of them. I didn’t necessarily mention them in the book, but capturing these things allowed me to brew over them in my subconscious. The physical object takes you into a subject.

Mary Wang: I can clearly tell that you like the secretarial part of the work—this is so beautifully organized. It’s almost as if you’re shaping the narrative through categorizing the folders already.

Olivia Laing: This is already quite far into the folder system! It’s like the Tetris thing again—the early stage of structuring a book really arises out of the accumulation and arranging of information.

Mary Wang: You said that Lonely City “cured” your own loneliness.

Olivia Laing: In the most simple terms, it was because I discovered it was a shared experience. But I really understood that for myself when I handled things that testified to people’s experience of feeling wounded or different or strange. On the last day I was in the Warhol archive, they asked me whether I wanted to see the abdominal corsets he had to wear after he was shot by Valerie Solanas. They were so tiny, and they were beautifully hand-dyed. They must have been humiliating for Warhol, but he wore them every day. They showed you how small he was, a 27-inch waist. Suddenly there’s a little damaged body in front of you. That was so bewitching and so softening of my own feelings of shame.

Mary Wang: In an interview you said that a lonely place is a homogenous place. Is New York becoming more lonely as we go, as it becomes more gentrified and homogenous?

Olivia Laing: You can see that the diversity of New York is seeping away. We’ve entered this horrific political moment in which people are voting consistently for homogeneity, for closed borders, for expelling otherness. It feels like Lonely City was about that tendency just as it began to show up, but with no sense yet of how powerful it was going to be. In the book I used the AIDS epidemic as an example, but the issues are equally true for any stigmatized community—the homeless, say, and certainly right now immigrants and refugees. But I should add that loneliness doesn’t automatically create the empathy that might challenge that. Teenage boys who decide to become men’s rights activists are also driven by loneliness—it can make you more socially awake but also more hateful.

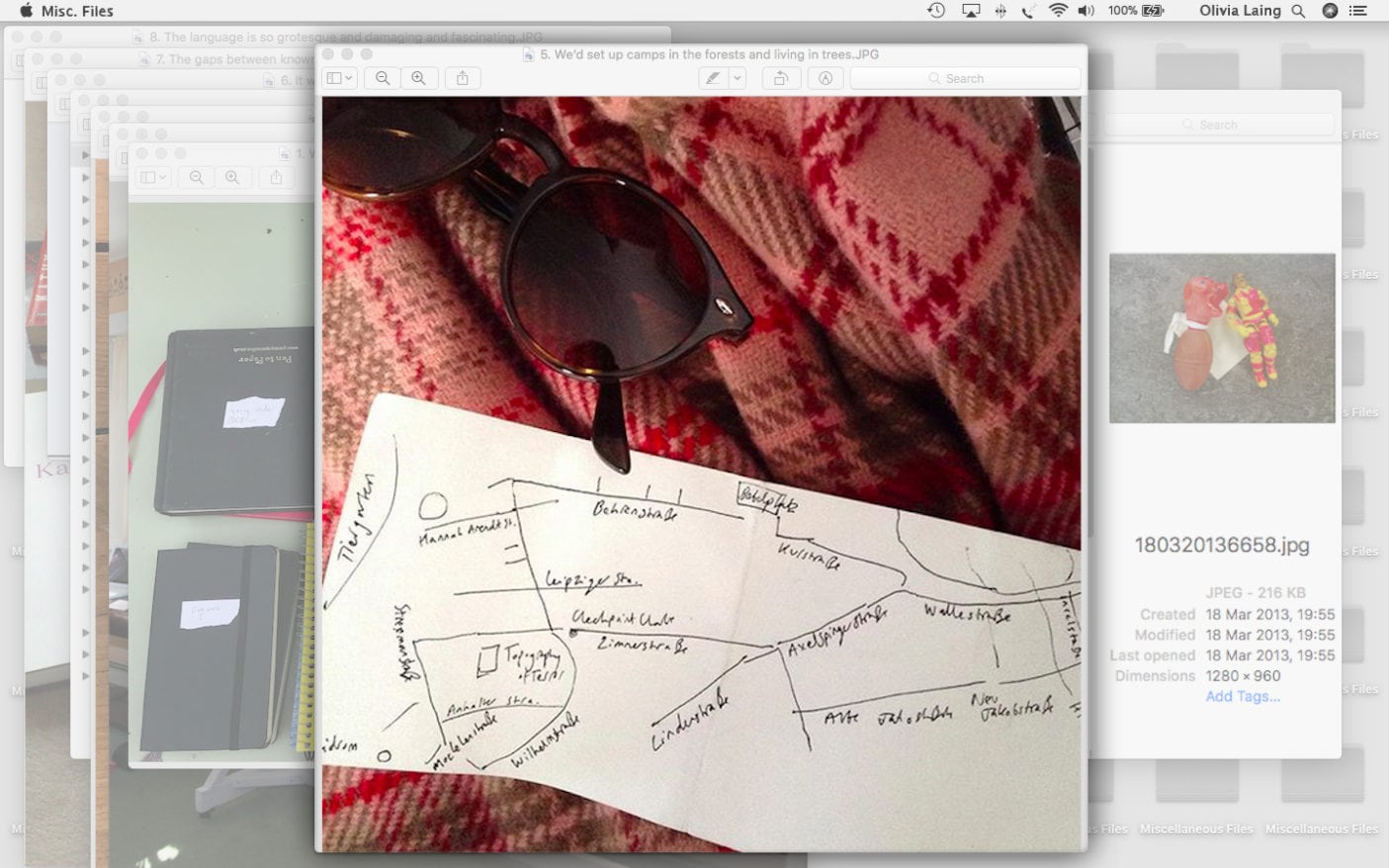

5. “We’d set up camps in the forests and live in tree houses”

Mary Wang: Where are we here?

Olivia Laing: This is the route to the Topography of Terror museum in Berlin, which is a scary place to go to now because it’s about the moment right before the Nazis came to power. This visit was for Everybody, my next book and the one I’m really struggling with. In part, it’s because I suggested the idea right before the big political shift of the last couple of years. The book thinks about why it’s so hard to inhabit a human body, because of racism, sexism, and our vulnerability to violence. But it also asks why the body is an ongoing powerful force, even in our own increasingly automated and disembodied age. I thought I would talk about how amazing protest is and how human bodies can change worlds. But I didn’t envisage that there would be Nazis walking through the streets of Charlottesville with tiki torches, so I had to recalibrate.

Mary Wang: You did protests yourself in your twenties.

Olivia Laing: That’s why I had a very rosy view of it. I was on road protests, arms protests, climate change protests in the ’90s. We’d set up camps in the forests and live in tree houses—that community felt utopian. It was powerful, people using their bodies to insist on changes to legislation, successfully. But the other problem with the book was that I realized that I couldn’t process the moment we’re in by way of the kind of nonfiction I usually write. It was all moving so fast. I was on Twitter twenty hours a day, unable to make sense of what I was seeing.

6. “It wasn’t meant for publication”

Mary Wang: How did you go from using a Nokia to announcing the start of your novel on Twitter?

Olivia Laing: I had this idea for a quartet of books, which I thought was really funny, so I tweeted it. The idea is that I was going to write a novel at the start of every decade, at forty, fifty, sixty, and seventy, and their titles would refer to different stages of cooking—crudo means raw in Italian. I used to love Twitter for the communal chat. It was a good resource. But it gradually got darker and darker until the president was literally using it to threaten nuclear war.

At the time I wrote that tweet, I was reviewing Chris Kraus’s Kathy Acker biography, After Kathy Acker, and I was really excited about the part in which Acker, as a young writer, was assigned by her teacher David Antin to go to a library, take a biography, and write it out in the first person. I liked the idea of that kind of theft, that illicit act of appropriation. I decided to start documenting everything that was happening around me, including what I saw on Twitter, through the persona of Kathy, who is a slightly cartoonish, paranoid, anxious hybrid of Acker and me.

Mary Wang: You said it was liberating to “just write.”

Olivia Laing: The rules of my experiment were that I had to write every day and that I wasn’t allowed to edit or even read it back. It wasn’t, I should add, initially intended for publication. It was a game I was playing with myself. But when I finished and did decide to publish, I also had rules for my editors, which were that it had to come out within a year of finishing—which is very fast for a publishing schedule—and that it couldn’t be edited in a traditional way. It was meant to be this slam-down experience, an exact accounting of living through a very turbulent period in time.

Usually I’m a very obsessive writer, but I needed to do something that was much more reckless and freeing, and it was the best writing experience I’ve ever had. It’s not sustainable though—if I wrote every book like that, it would be disastrous. But perhaps it has opened up possibilities for a hybrid form, between the kamikaze and the pedantic.

Mary Wang: Is there an advantage to writing without publication in mind?

Olivia Laing: It was also the most private experience of writing I’ve ever had. Everything I had written before was sold on proposal, so it’s always been written with the knowledge of eventual publication. With this, I made exactly what I wanted to make. We worry so much about publication, especially young writers. But actually, experimenting is necessary. That’s very Acker, to experiment for its own sake.

Mary Wang: You describe it as something that was written so quickly. Now the book is getting all this praise, with some hailing it as a reconfiguration of the novel. There’s a strange schism in that—do you identify with those descriptions?

Olivia Laing: To be perfectly honest, I don’t think they would have published it if I didn’t have a publishing record and this was my first novel. It would have been such a thing to ask a publisher to not edit the work! So I know I’m in a very privileged position in having a body of work already and publishers who trust me. But it doesn’t come out of no context either. It wouldn’t exist without books like Ali Smith’s Autumn, which made me realize that you can write things that are very close to their moment and that a publisher can be cajoled to hasten their timeframe.

Mary Wang: A lot of people use the trendy term “auto-fiction” to describe everything that’s remotely personal. But I’ve always thought of it as a way to not feel burdened by the censorship, or limits, of nonfiction.

Olivia Laing: Absolutely. In my nonfiction, the personal revelations tend to be quite extreme, but also very spare. I use the “I” as the camera, the guiding consciousness that carries you through. In Crudo, I plagiarized my life and gave it to this character, Kathy. I wanted to capture exactly what a particular moment felt like as it was experienced, totally raw and without the benefit of hindsight. Stealing personal material from my own life was a means to that end, a way of taking an exact print of what it was like to live inside the chaotic and frightening summer of 2017.

I’m slightly wary of the term “auto-fiction,” but a lot of books I love receive the same categorization. Chris Kraus smuggled radical politics and feminist art history lessons into I Love Dick. It’s such a neat trick. You read about some horrific emotional interaction that excites you, and she uses the energy of that to take you somewhere else entirely.

Mary Wang: In I Love Dick, the protagonist asks, “Why is female vulnerability still only acceptable when it’s neuroticized and personal; when it feeds back on itself? Why do people still not get it when we handle vulnerability like philosophy, at some remove?” Is the term “auto-fiction” used more derogatorily for women than men?

Olivia Laing: Yes! It’s like, “Oh, they don’t even know how to write a novel properly!” People are policing what’s real and what’s made up—but who cares? That’s not the question.

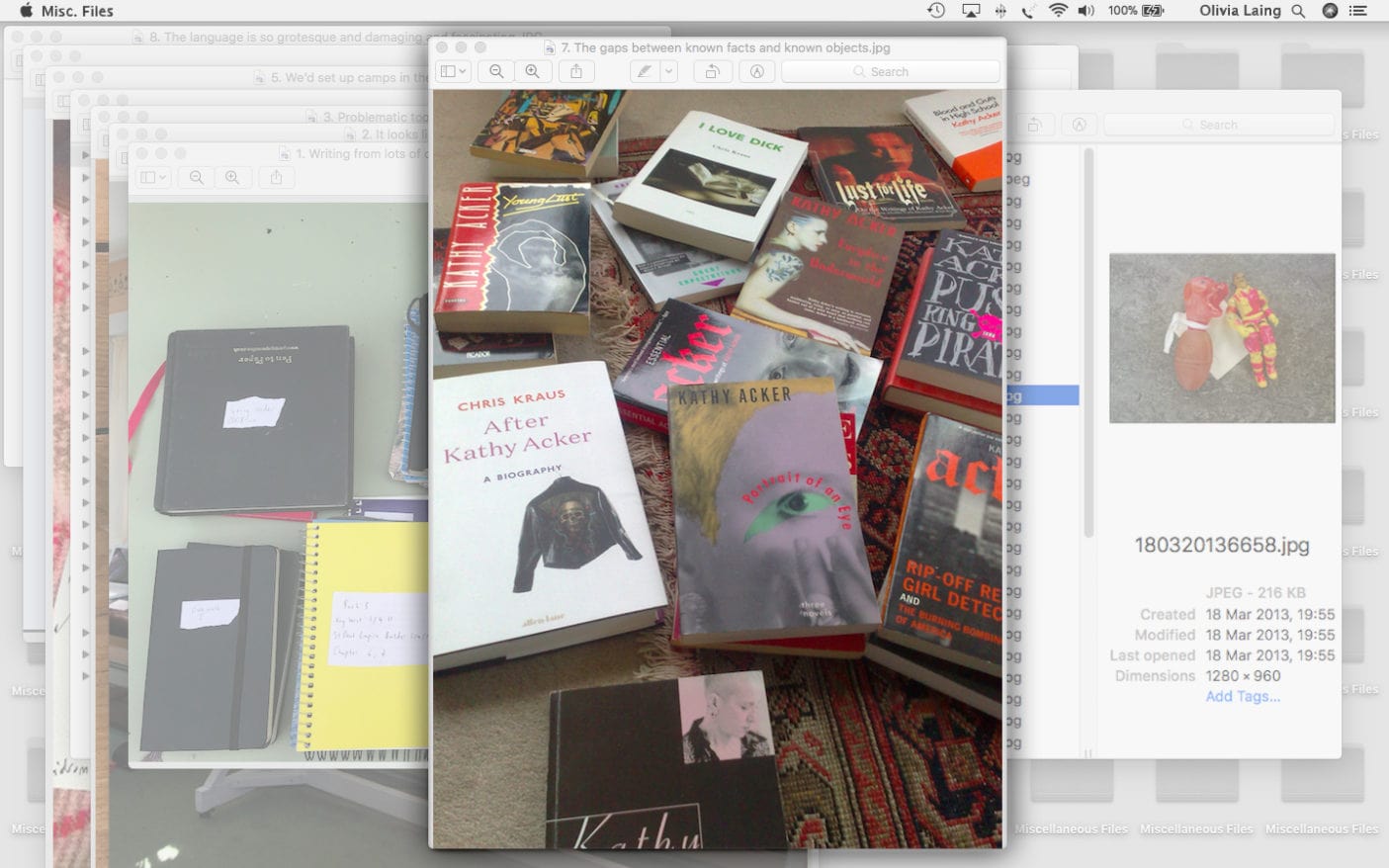

7. “The gaps between known facts and known objects”

Mary Wang: Kathy Acker!

Olivia Laing: Acker’s books are made up of so many other people’s books; she’s stealing Dickens, Don Quixote, and putting them to her own ends. That seems so liberating to me. If you need this, take it. It’s yours.

Mary Wang: In your interview with Kraus, she said that you share a horror for making things up.

Olivia Laing: Yes, and Acker shares it too. Coming from a nonfiction background, I recoil at the idea of staging a scene that didn’t happen. I’m interested in the gaps between known facts and known objects, not in trying to fill the gaps with my own material. I made a list at the end of Crudo of the Acker quotes I used: the book is stitched together smoothly, but I want the reader to know that there are gaps between my words and hers. That feels exciting, like making a collage. I like being constantly interrupted by somebody else’s voice.

Mary Wang: In Crudo, Kathy asks, “What is art if it’s not plagiarizing the world?”

Olivia Laing: What Acker did is close to what Warhol was doing: Why not take things that are there and use those as your raw material?

Mary Wang: In that way, both Kraus’s Acker biography and Crudo are books on the artistic process. One describes it from a distance and the other is a more intimate look where the reader witnesses the artist’s decision-making process as we go. What was your relationship with Acker previous to this project?

Olivia Laing: I came up on her books when I was in my teens, and I loved them. But five, even three, years ago I would’ve thought of her as an experimental writer from the 1980s, and she wouldn’t have felt so urgent to me. She hasn’t changed, but the world has circled back. Terrorism, sexual violence, abortion, all her themes are suddenly back in the news. Her mode of writing feels relevant too, the avant-garde refusal of realist thinking. A president tweeting about nuclear war would not surprise her for a minute.

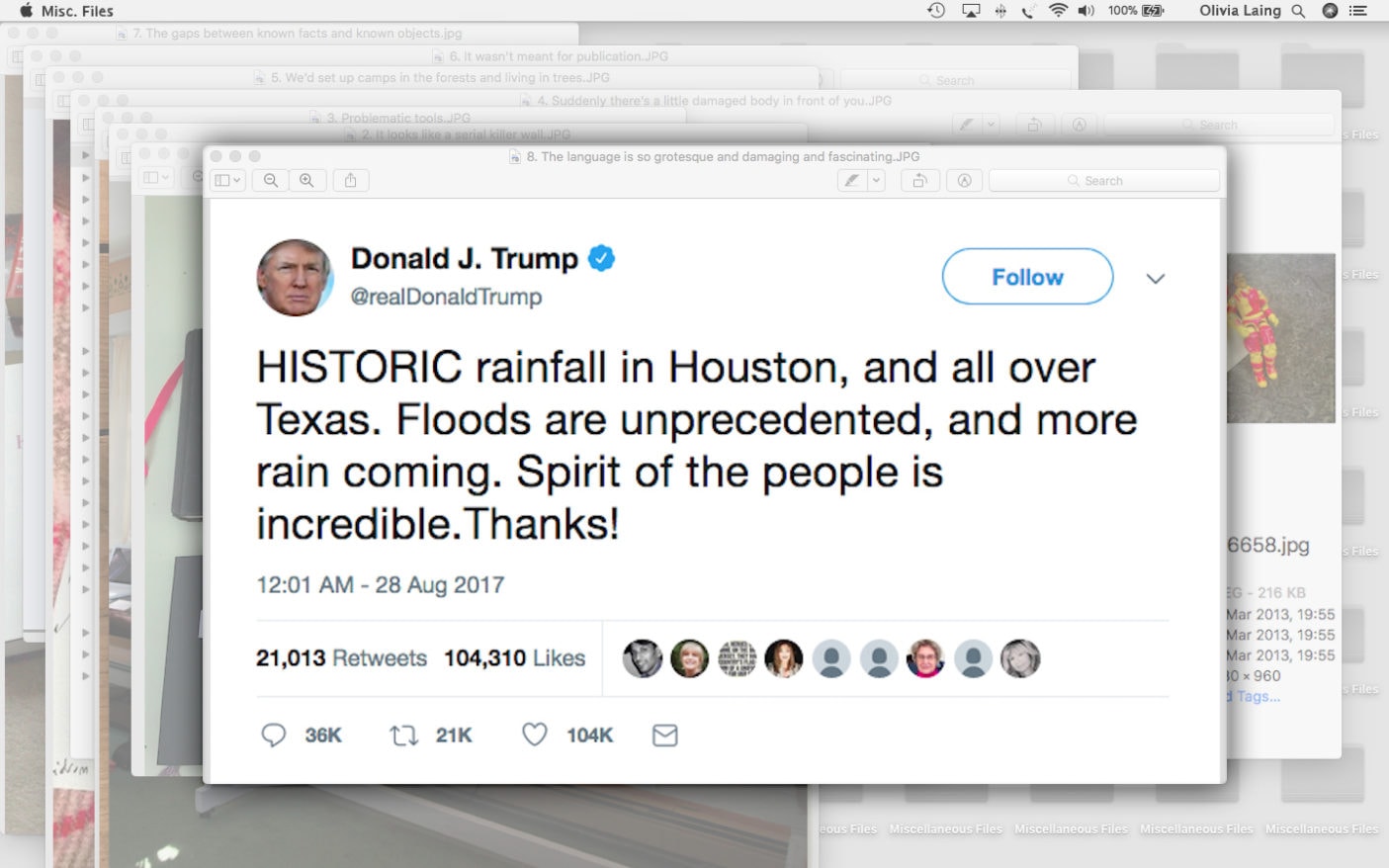

8. “The language is so grotesque and damaging and fascinating”

Mary Wang: Crudo is capturing the experience of this moment, where reality is stranger than fiction—if you would literally write this down as a novel people wouldn’t believe it. What was your strategy for capturing this sensation?

Olivia Laing: Anything striking that I encountered on my travels through Twitter each day would go straight in, like Trump’s tweets around the Houston floods and Charlottesville. This sense of being invaded by news, overwhelmed by so many different and toxic voices is part of what it’s like to live through this moment, and I wanted to recreate that cacophony and sense of splintering in fiction. Also, the language is so grotesque and damaging and fascinating, I felt compelled to record it.

Mary Wang: These tweets are often directly embedded into web articles now, but in Crudo, they’re woven into the text. The sentence structure, which is so different than in your other books, mimics their pattern. It’s without punctuation, without break. It’s under-punctuated.

Olivia Laing: That’s why there are no speech marks throughout the book—the bombardment by the media means that our minds are populated by the voices of strangers. That’s the same thing as an artist’s mind anyway, in the sense that you have your own thoughts and those of the people you’re writing about. It never stops—there are no full stops.