When the writer Kwame Dawes began searching for a press that published African poetry, he noticed a disconcerting void. “It became clear to me that there was not one single press in the world that was devoted to publishing African poets,” he explains. “That just seemed unbelievable.” The few poetry publishers across the continent tended toward small-scale, regional distribution, meaning that even when African poets did release books, their range of influence rarely extended beyond the boundaries of their own home countries.

Dawes began to see that the flow of literature into Africa was also constrained. As he read the submissions of African poets for a literary contest, he noted that while the poets wrote with urgency and passion, the poetics of certain authors seemed surprisingly dated. Gauging by their work, the contestants hadn’t read poetry more recent than the Modernists.

Dawes surmises this is an issue of access, not aesthetics: African libraries tend not to stock contemporary poetry, so young African poets are often dependent on the traditional fare assigned in their high school and college classes. Without the means to have their voices heard or engage with other current writers from the rest of the continent and the world at large, talented African poets, Dawes argues, are being marginalized from evolving global conversations about contemporary poetry.

Aspiring toward a creative solution, Dawes worked with a host of concerned authors, including Chris Abani, Matthew Shenoda, Gabeba Baderoon, Bernardine Evaristo, and John Keene to found the African Poetry Book Fund. The project, launched in early 2014, is a multifaceted effort to engage with and promote the poetic arts of Africa, namely by publishing African poets and establishing poetry libraries in various African countries.

As Dawes and his collaborators at the African Poetry Book Fund are well-regarded writers and educators, they’re able to utilize their authority and influence in the Western literary world to grant credibility to, and build an audience for, the writers they publish. In the face of monolithic and often demeaning discourse about Africa, Dawes describes his publishing endeavor as “an archival process that mitigates the silence…the presumption that nothing is being said.”

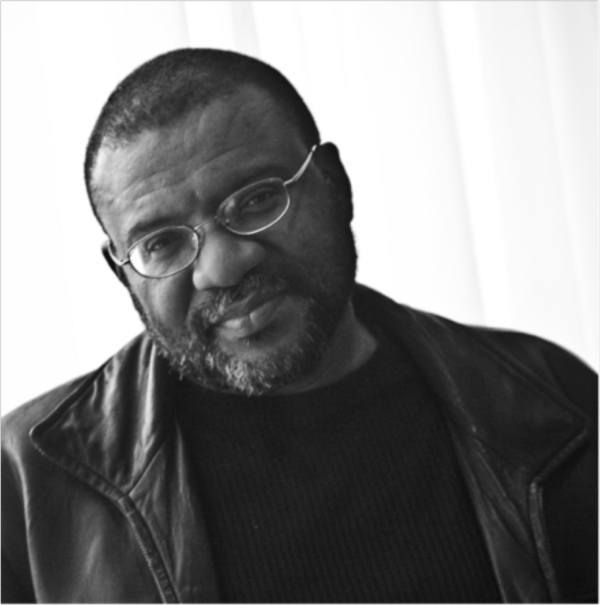

Born in Ghana and raised in Jamaica, Dawes has published seventeen books of poetry, most recently Duppy Conqueror: New and Selected Poems. He began his career as a playwright, and much of his drama, fiction, and nonfiction delves into the history and aesthetics of reggae music. He spoke with Guernica in 2011, just after his multimedia website, “Living and Loving with AIDS in Jamaica,” won an Emmy award. Dawes teaches in the Pacific MFA writing program, serves as editor of Prairie Schooner, and is Chancellor’s Professor of English at the University of Nebraska. During our conversation, he laughed often, and easily, speaking in a steady tone reminiscent of a long distance runner’s gait—as if conserving his energy for the miles ahead.

—Aisha Sabatini Sloan for Guernica

Guernica: I was reminded of your project recently after seeing a box in the library labeled “Donate Books to Africa.” The African Poetry Book Fund not only establishes libraries in Africa but also brings books from African writers to a global audience. How did it come about?

Kwame Dawes: I was trying to identify publishers of African poetry. There are places in South Africa that publish largely South African poets, and there have been occasional presses in other parts of Africa that have published poetry, but for the most part they haven’t done so. It became clear to me that there was not one single press in the world that was devoted to publishing African poets. That just seemed unbelievable. I was meeting so many poets from different parts of Africa who had no easy access to publication, and I felt that we should start something like that.

There is constantly this remarkable arrogance of people who, because they didn’t know who I was, suddenly think they had discovered me for the world. It’s a Columbus fixation.

I got a team of like-minded people together, and we began to conceive of this thing called The African Poetry Book Fund. The commitment was to publish at least four books of poetry each year, and a suite of chapbooks if possible. I pitched the idea to the philanthropist and poet Laura Sillerman, and that relationship began the funding basis for the African Poetry Book Fund. Our goal is to publish African poets in as many ways as possible.

Guernica: Matthew Shenoda wrote in this magazine about the problems with the use of the term “discovery” when talking about the work of international authors, who have established careers but are unfamiliar to American audiences. Have you encountered that kind of language while working on this project?

Kwame Dawes: I have lived under this problem all my life as a writer. My primary publishers are in the UK and in Canada. I’ve published in the US and I have a US publisher, but there is constantly this remarkable arrogance of people who, because they didn’t know who I was, suddenly think they had discovered me for the world. It’s a Columbus fixation. It wasn’t there until they saw it. The idea of discovery implies that this writer is a new writer, that this writer hasn’t been doing the work they’ve been doing all this time. Then it gets complicated by the ways in which people try to own the discovery, and also the way that people try to manipulate that so-called discovery.

Then there are problems related to the idea of engaging a continent like Africa and writers that are not yet part of American imagination. There’s anxiety [among American audiences] about whether or not to trust the work. But the good news is that we are writers who have lived in these worlds. We see the inherent value in these multiple, sometimes conflicting poetics and that gives us permission to present the work in a context that gives it dignity.

Finally, the work itself does the job. These writers that we’ve been publishing are remarkable. I think of somebody like Clifton Gachagua, whose book Madmen at Kilifi is probably one of the best first books that has been published in the past year anywhere. I can say that with absolute confidence. The work will eventually do what needs to be done to clear a lot of that nonsense away.

Guernica: You’ve talked about the idea that publishers like fiction from Africa because it does the work of “explaining the continent.” How is the work of poetry different? Or is it?

Kwame Dawes: We are drawn to story. The idea of telling stories is fairly universally understood. Fiction tends to be discursive—it is very well suited for creating context and, yes, “explaining” whatever may be happening in a culture. The lyric and ritual nature of poetry, along with its constant demand for brevity and suggestion, make it less suited to do this kind of work. As a result, the experience of engaging another culture is quite different with poetry. Historians, social scientists, and political scientists are quick to recommend works of fiction to their students who may want to understand something of another culture. So even though Christopher Okigbo and Chinua Achebe were essentially contemporaries writing about the same country during the same period, and while both were quite brilliant writers, everyone knows Things Fall Apart and few people know Limits. Chris Abani is better known as a novelist than as a poet despite the fact that his book Sanctificum is probably one of the most important collections of poetry published in the last few years.

But the big reason that I think there’s an inclination to publish fiction is simply that fiction sells in ways that poetry just doesn’t sell. A publisher can invest in a novelist from India, say, or a novelist from Botswana because fiction is an area that actually can generate a profit. Poetry doesn’t have that margin of success.

I don’t have this capitalist notion that if it sells a lot it means its good. I have the view that if it’s good and important, it needs to be subsidized and it should be subsidized.

Consequently, poetry has to be subsidized. And I am of the belief that it’s important enough to subsidize. I don’t have this capitalist notion that if it sells a lot it means its good. I have the view that if it’s good and important, it needs to be subsidized and it should be subsidized.

Guernica: Can you talk about the remarkable cover art for the African Poetry Book Fund’s book series?

Kwame Dawes: We’re trying to use African art and African artists. For the chapbook series, we’ll have a single artist whose portfolio we draw upon to make covers for each of the books in a box set. Laura Sillerman introduced me to the work of the brilliant Nigerian artist Adejoke Tugbiyele. She experiments with installations and fabric sculptures, and the work is stunning for color and for the assertive sense of her Nigerian sensibilities in the work. Adejoke recommended our second artist to us, Imo Nseh Imeh, a brilliant and accomplished scholar of aesthetics and a splendid artist in his own right. He, too, is Nigerian, and we decided to go with his paintings and drawings, which have a fluid language and an enduring fascination with the human body. What you get is this collection of poems along with this gallery of remarkable art of a single artist. And it’s great that we can find the right kind of artist that can work with the sensibilities of the different poets because the poets are all quite different.

Guernica: Setting up libraries in various African countries is an important facet of the African Poetry Book Fund. How did that emerge?

Kwame Dawes: All the people on our editorial team teach writing and judge poetry contests. You learn very quickly that there is a direct correlation between what you read and what you end up writing. So in our conversations about these manuscripts, we were all kind of taken aback by the passion, the urgency of the things being expressed. We were also struck by the significant proportion of these writers whose poetics were so dated. They went back to the work from the earliest Modernists.

It didn’t take long for those of us who grew up in Africa, and have lived and worked in Africa, to recognize what was happening. [These poets] were modeling their poetics on the literature they were reading and studying in high school or university. There is no access to contemporary poetry in the libraries. So what they have access to is the work on the academic syllabus.

I remember when I used to teach in England in the ‘90s, first entering the Poetry Library at the South Bank Centre [Britain’s most comprehensive library for poetry since 1912] and being completely moved by the availability of these books. I could read and make my notes and see what other poets were doing and to start to formulate my own sense of voice in light of other people. We felt that if we could give the writers [in Africa] a chance to have that kind of experience, that would be great.

Guernica: Where do the books for the libraries come from?

Kwame Dawes: I judge a bunch of contests. Usually if I judge a national contest I’ll end up with a hundred, two hundred, sometimes up to 250 books of poetry. At Prairie Schooner, each year we get in several hundred books for review. We have a book sale at the end of the year, make about two or three hundred dollars selling books for five cents or ten cents or whatever. I thought “Well, that’s a bit of a waste.” I mean, you’ll miss the three hundred dollars, but if we can give those books to writers who have no access to those works then that would be wonderful.

We came up with a very simple plan: if the poets and arts organizers in those countries that we selected could find a space, furnish that space, get the shelving and find the staffing by themselves, we could send them books. We settled on five places: Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Botswana and Uganda. And that’s because of the individuals who were there who could facilitate this happening. We sent each of those countries about five hundred books and a number of journals. And we managed to get places like Poets and Writers to donate an online subscription to each of these libraries.

All the libraries have now had official openings except the one in Kenya, which will open in February. We’ll ask these countries to start building their own collections. Then we’ll try other countries. So far a lot of places have been asking to be part of it. The response has been fantastic.

People who say the physical book is dead have not been to other parts of the world. This is just ridiculous. Many of these places, because of colonialism and exploitation, have not yet even had the chance to engage in print culture.

Guernica: A lot of your projects in the past have been multimedia. Is it possible that the African Poetry Book Fund could expand beyond poetry?

Kwame Dawes: That’s a good question, and the answer is: not really. I worked hard to simplify this project. Once people start to see it working, then everybody has ideas about you could do this, and you could do this, and you could do that. We can do this much. And if we do this, then somebody else can do the other thing. There are already wonderful resources for multimedia, for spoken word versions of what we are doing. Some of our poets are performance poets. Badilisha poetry is a stunning website with this range of African poets performing.

The bottom line is that we are publishing books of poetry. The reason that we’re doing it is because nobody has done it. We are still investigating the possibility of e-books and publishing digital versions. But I think that people who say the physical book is dead have not been to other parts of the world. This is just ridiculous. Many of these places, because of colonialism and exploitation, have not yet even had the chance to engage in print culture. So, straightforwardly, we publish books.

Guernica: What is in store as the project grows and develops?

Kwame Dawes: Well the first thing that happens is the work. The work is amazing. There was a reading at AWP last year or the year before. The reading was so powerful and so moving because people were discovering these voices, seeing voices that they never knew existed. We are just finding a mechanism to make really remarkable work available to the world.

Also there is the idea of a kind of archival process, a process that mitigates the silence. The presumption of silence is that nothing is being said. That nothing is being written. And this is why publishing is so important. It reminds us that something is being said, something is being written. And we are preserving that. And this is why I have no problem with the subsidizing of the work. We need to have some kind of archival process; otherwise it disappears. And I just can’t abide by that.

Guernica: It seems like most of the donations for the libraries will be exported from the West, at least at first. But at the beginning of our conversation you mentioned the historically regional nature of publishing in Africa—South Africa publishing South African poets, and so on. So, does your project also strive to introduce African poets to other African poets?

Kwame Dawes: Africa, as you know, is a massive continent made up of forty-seven countries, and up to two thousand different languages. Consequently, it is a mistake to regard communication across that continent as a straightforward thing. Book publishing, book distribution, and book trade in Africa, as in many other places, is Western-centric—things flow to the West before ever getting back to Africa. As a result, many African poets are not aware of the work being done by other African poets on the continent. This is why the Badilisha Poetry Exchange website is such a wonderful and groundbreaking entity. As many African writers have said, that website has offered them, for the first time, a wonderful forum to discover other writers in different countries. Hopefully, someday we will be able to improve the distribution of books across the continent, but in the meantime, we hope that the poetry libraries will offer an opportunity for African poets to actually get ahold of the work of their fellow African poets.

Guernica: Did you benefit from a particularly meaningful mentorship when you were beginning as a poet?

Kwame Dawes: No [laughs]. I had encouraging people. I really started as a playwright. For the first ten years of my writing life, eighteen to about twenty-eight, I ran a theater company and I was writing plays. Because of my playwriting, I received a fellowship to the Iowa International Writing Program. And while I was there I met poets like Bole Butake from Cameroon, Femi Osofisan from Nigeria, writers from all over the world. I was twenty-four years old. I was the youngest person among forty other writers. But they were very encouraging to me. They affirmed that I could write poetry and that helped me a lot.

They gave me a home, they gave me a place where I knew my work would be taken seriously year after year. And if I can create that space for other writers from different parts of the world, then I think I’m doing something really important and valuable.

I never had the systemic structures that we’re trying to create. But I had opportunities and I had the support of people. Peepal Tree Press started about three years before I sent them my first manuscript. Until that point there were very few opportunities for Caribbean poets. Now Peepal Tree Press puts out more than half of the poetry that is published from the Caribbean. And I’ve benefitted from that. They gave me a home, they gave me a place where I knew my work would be taken seriously year after year when I submitted work for consideration. And if I can create that space for other writers from different parts of the world, then I think I’m doing something really important and valuable.

Guernica: Lately there have been a number of critiques about the lack of diversity in MFA programs, most visibly Junot Diaz’s essay in The New Yorker, “MFA vs. POC.” Can you speak about your experience at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and what you encountered as a person of color in that space?

Kwame Dawes: I was in the International Writing Program, which was a six-month fellowship [it is now a ten-week residency], and frankly, the only people who were there were either people of color or foreign people. So I don’t know what craziness goes on in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. But here’s the thing: writing is challenging in the best of circumstances. And there’s no question that when you enter a program and you are the only minority in that program, there’s such a burden on you. The fact is, too many people who teach creative writing are ignorant. They haven’t read anything beyond the limited range of things that they’ve read. So when they see something that looks a little different, they fall into a very American attitude, which is to say, “If I don’t know it then it can’t be that important.” So because of that, very often the critiques that are made of poets of color come out of the ignorance of those people who are teaching or the ignorance of those people around them. It can be extremely limiting. And it can be extremely damaging.

But that said, one can still do good work in that environment. If we treat the workshop process as an engagement with craft primarily, then mastering the craft is one exercise that we can do. And it can benefit us even as we protect our own path as writers and our path as poets. One way to solve the problem is to employ more people of color to teach in creative writing programs. And to have greater expectations about the aesthetic range of the people who are teaching. They should have a broader sense of poetics so that they can be valuable to the evolving student body and the evolving poetry world. Because it’s changing. There’s no question about it. Black poets, Latino poets, are really having a significant impact on American poetics today. So, somebody has to catch up.

Guernica: You’ve talked about how one of the blessings and the curses of your life is that you have so many projects going at the same time. I wonder if you could tell me what’s next, or what’s concurrent?

Kwame Dawes: Sometimes I don’t even want to think about it! Chris Abani and I are in discussion about a new series of chapbooks that are fiction-based, still looking at Africa, and so we’re seeing how that would work as a project. We’re also developing a project with Matthew Shenoda for critical essays about poetics. I’m constantly thinking of ways to open up possibilities for publishing, particularly in the Caribbean. I’m writing my own work. I don’t know what else. I’m saying I don’t know what else but I can guarantee you there’s a ton more. But it’s quite funny because every project for me, I try to keep it in a compartment until it needs to be dealt with. And then it’s dealt with. But I think I’m doing enough now to be able to let the other stuff go for the time being.