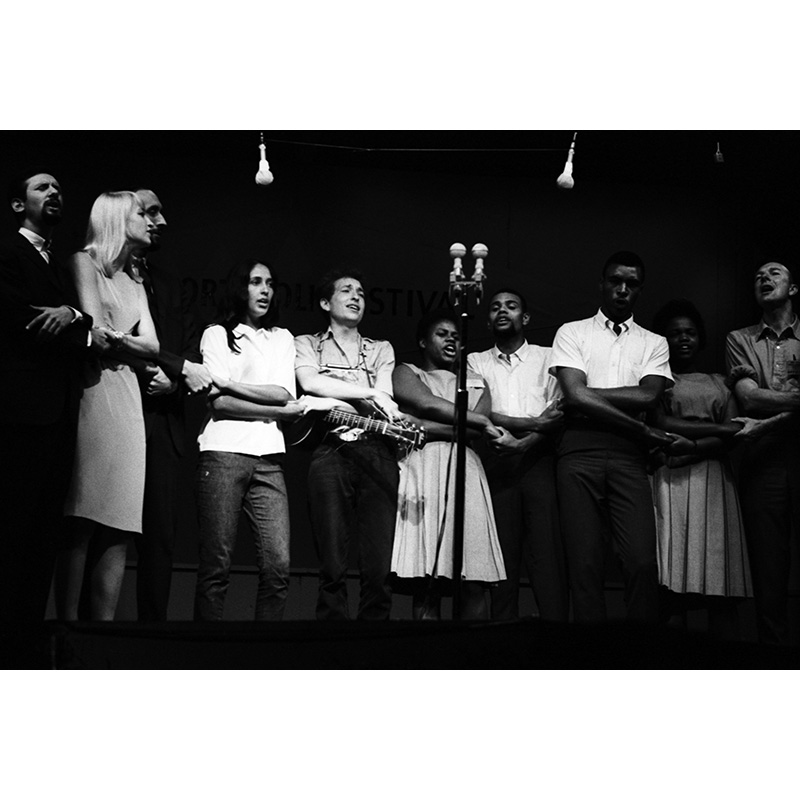

NEWPORT, RI - JULY 1963: An encore ensemble (L- R: Peter Yarrow, Mary Travers, Paul Stookey, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Bernice Reagon, Cordell Reagon, Charles Neblett, Rutha Harris, Pete Seeger) sing the civil rights anthem "We Shall Overcome' at the finale of the Newport Folk Festival in July, 1963 in Newport, Rhode Island. (Photo by David Gahr/Getty Images).

Kanye West was bold to sample a song about a real-life double lynching for the Yeezus track “Blood on the Leaves,” on the perils of celebrity and love. But it has none of the gravitas of the sample, “Strange Fruit,” famously performed by Billie Holiday at the nation’s first integrated nightclub, Café Society, in 1939, and later recited by folk singer Josh White at his testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1950. White wasn’t a Communist Party member, but was blacklisted, ostensibly, for the progressive company he kept in New York City and the protest songs he sang about the reality of racial violence, including his dark, intimate, and mostly a cappella version of “Strange Fruit.”

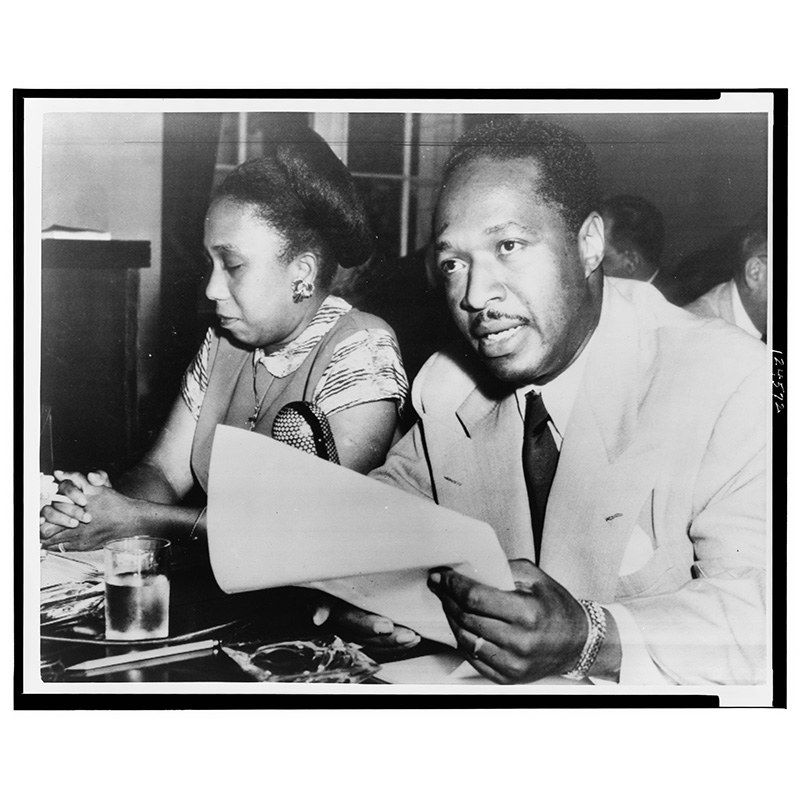

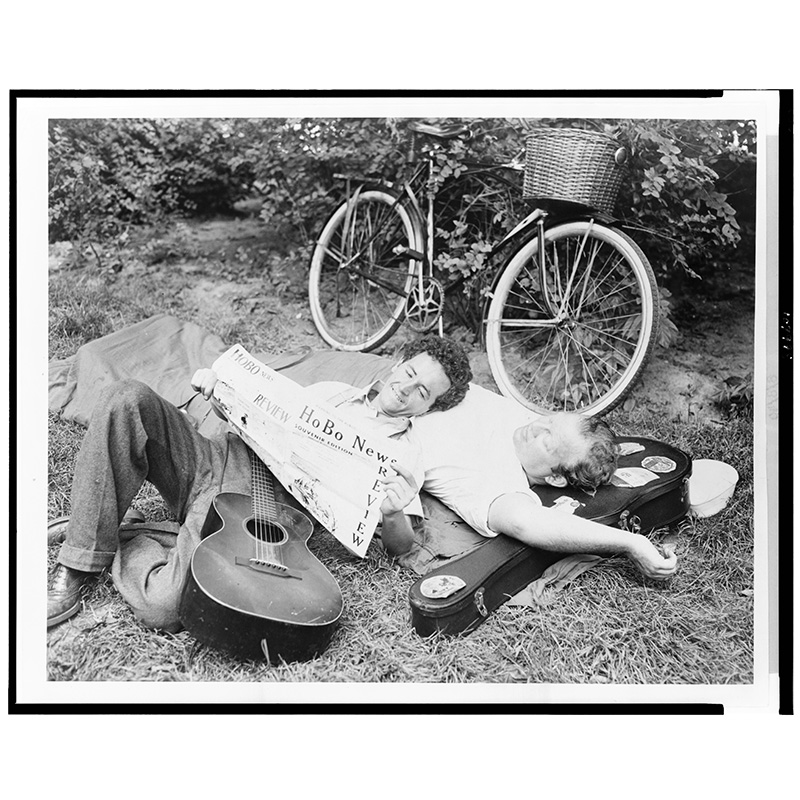

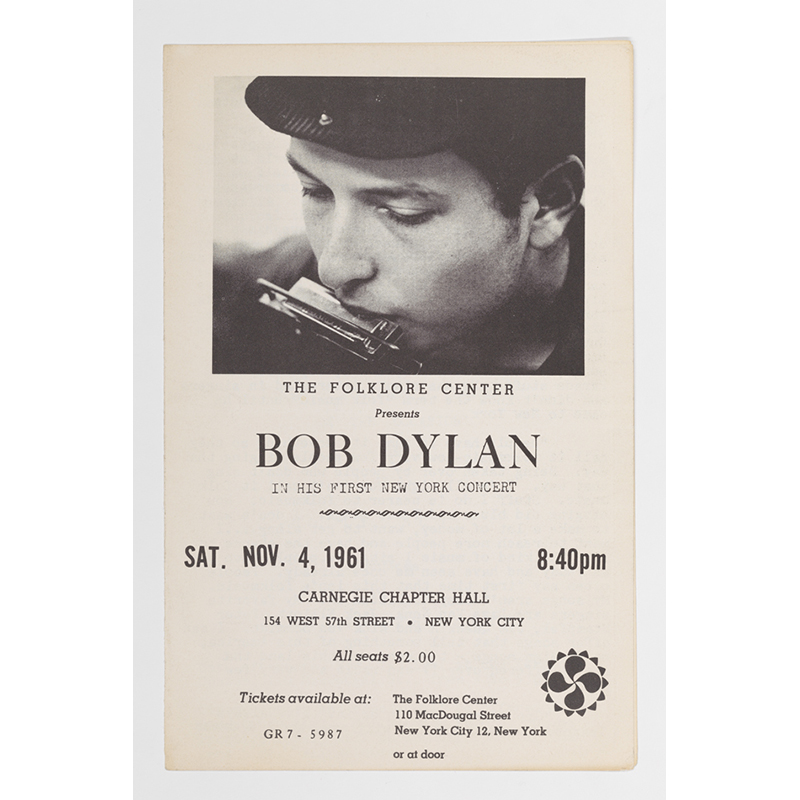

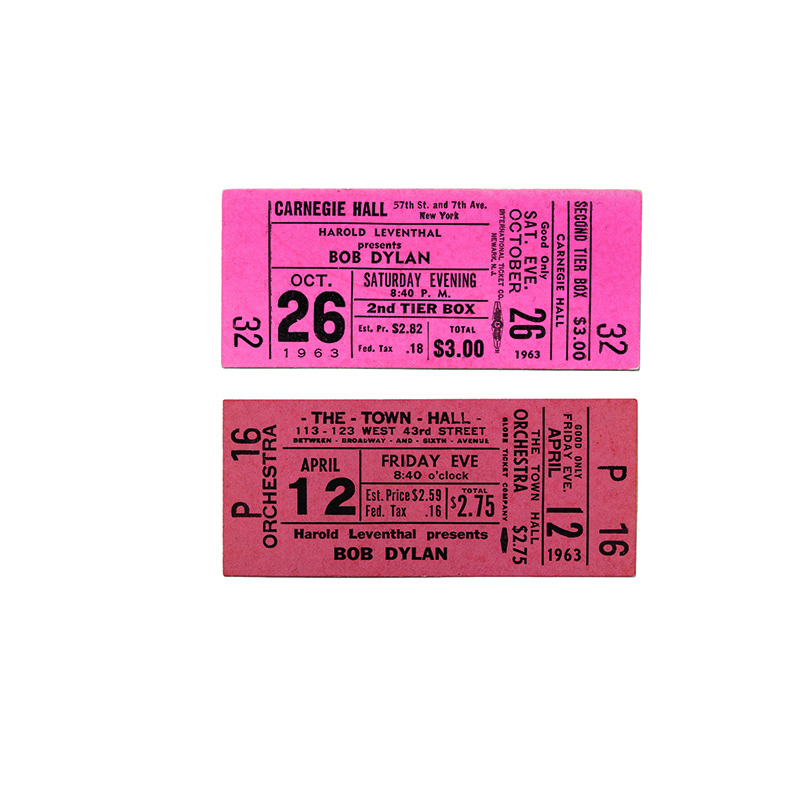

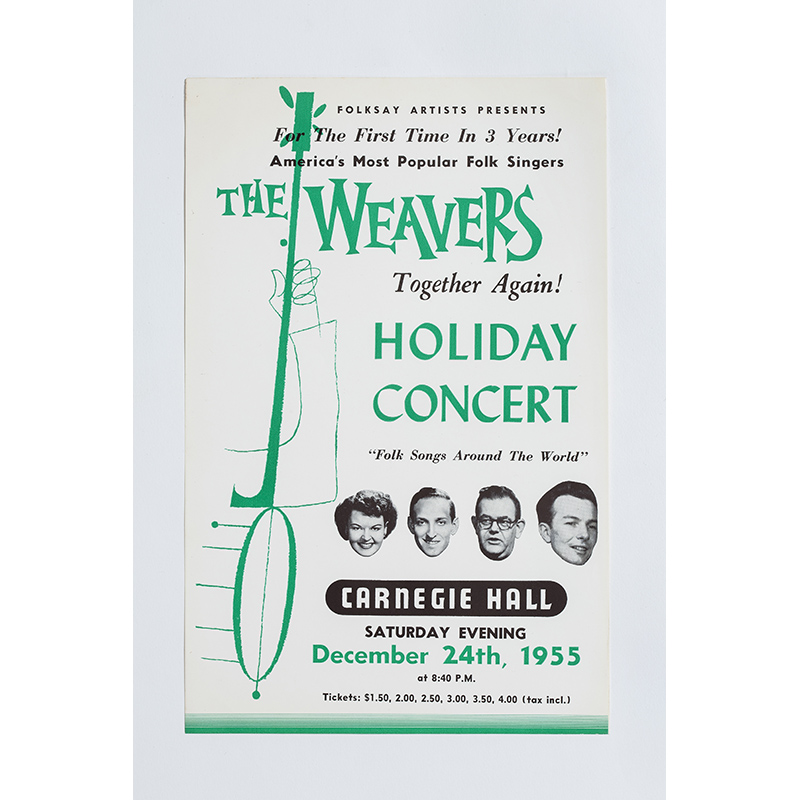

A blown-up photograph from White’s 1950 testimony hangs on the wall in Folk City: New York and the Folk Music Revival, on view at the Museum of the City of New York through January 10, 2016. The exhibition showcases folk musicians like Josh White, Dave Van Ronk (recently fictionalized in the Coen brothers’ Inside Llewlyn Davis), Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, and other aficionados who moved to New York City to perform and record American roots music as a tool against segregation, war, suburban conformity, and commercial taste. Folk City allows visitors to listen to selections from the seminal Anthology of American Folk Music on headphones stationed throughout rooms filled with folk revival memorabilia: concert posters, ticket stubs, album covers, magazines, lyric sheets, Pete Seeger’s banjo, Lead Belly’s twelve-string Gibson, candid photos like one of a flippant Woody Guthrie in Central Park, and Odetta’s dashiki.

Folk City not only illuminates the acumen and virtuosity of these citybilly artists through song, but also lets them speak through handwritten letters and interview footage. In the 1946 documentary To Hear Your Banjo Play, which plays on loop near the entrance, a twenty-something Pete Seeger explains that what’s exciting about folk music is what’s exciting about all music: it never finishes, and continues down the line of generations through artistic larceny and adaptation. But as the journey of “Strange Fruit,” from White’s testimony to Yeezus’s auto-tune accompaniment, suggests, no one knows what future generations will do with the music meant to change the world.

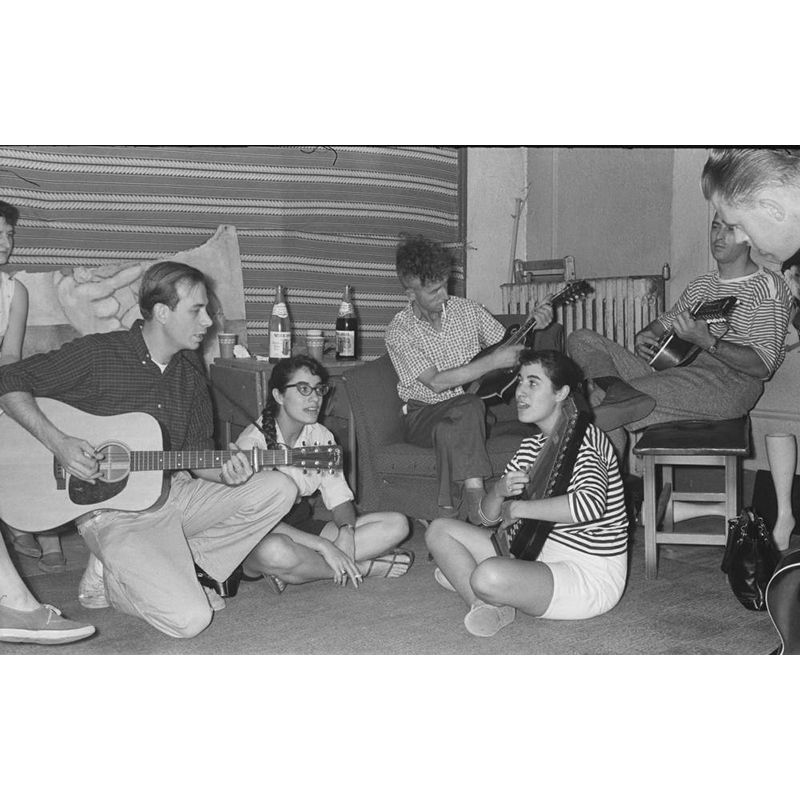

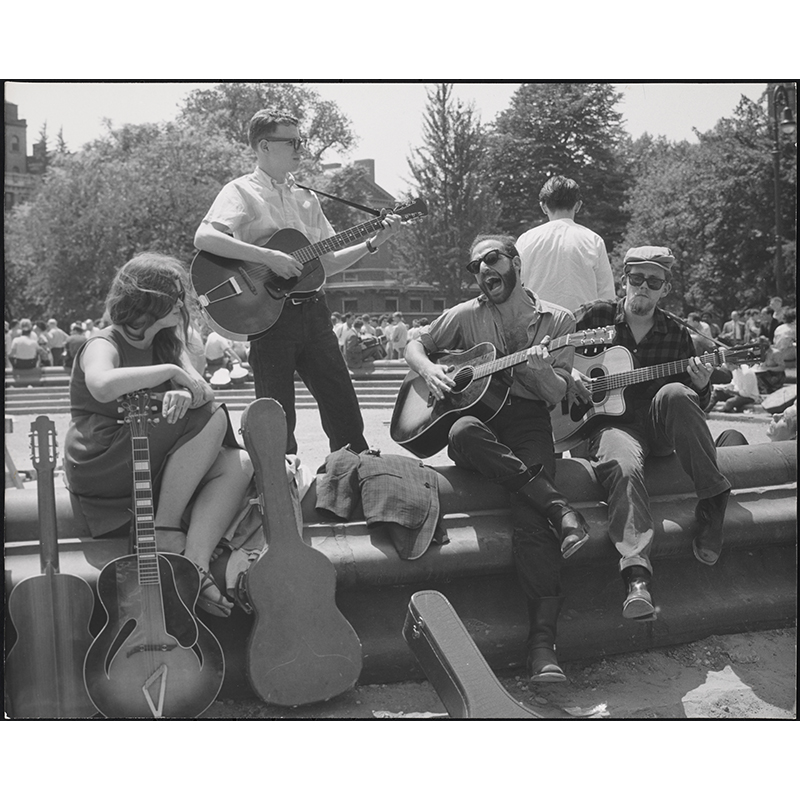

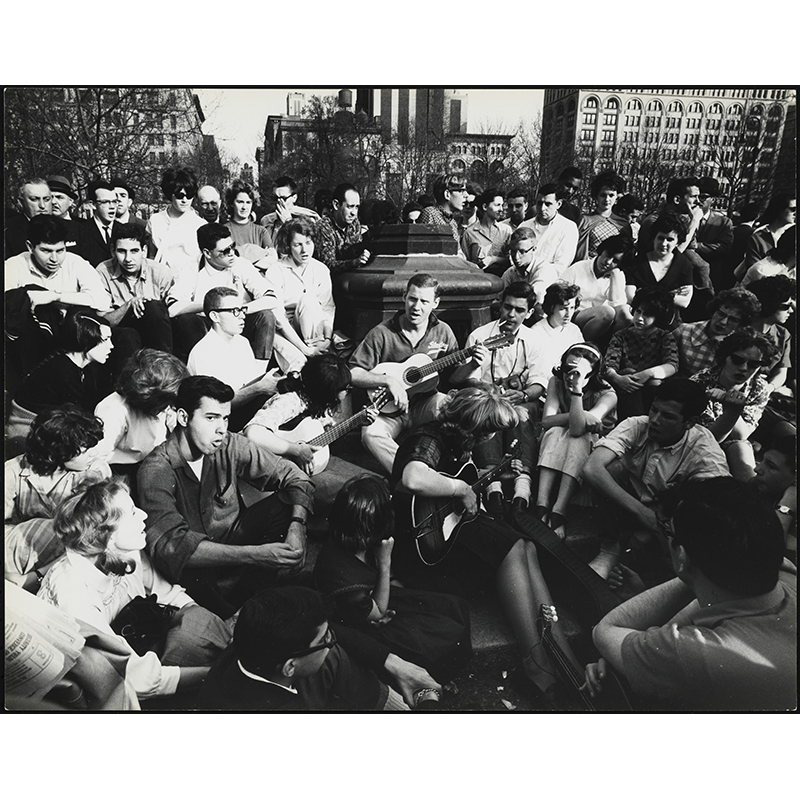

New York City from the 1930s to the early 1960s might seem an odd place for a revival of rural blues, gospel, ballads, and bluegrass music. But in many ways the city in those decades was an ideal setting in which to popularize what singer Brownie McGhee described as the “music of just plain people.” The Depression displaced Southern and rural musicians like Josh White and Lead Belly, who moved to New York to find audiences in venues like Café Society, the Village Vanguard, and, later, Gerde’s Folk City, whose original street-front sign hangs on display in the exhibition. Radio stations, among them CBS Radio and WNYC, invited folk artists like Woody Guthrie to perform on air. Pete Seeger and Alan Lomax, a musicologist who gathered folk songs from the Southern backcountry for the Library of Congress, started the folk magazine Sing Out! in 1950. The city was home to folk record companies, including Vanguard, Elektra, and Folkways Records, which compiled and released the folk revival text Anthology of American Folk Music in 1952.

As the “Becoming Folk City” section of the show makes clear, the music of the folk revival was consciously political from the start, and Folk City highlights the progressive causes that became part and parcel of the art. The exhibit exhumes old songbooks of the radical labor movement, like the Red Songbook, which was published in 1932 by the Communist Party-founded Workers Music League, and the museum walls are painted a deep red. A display case holds an original copy of Red Channels—the right-wing book that warned about the Communist infiltration of the entertainment industry—and the $500 receipt for Seeger’s bail after he refused to give names during the McCarthy witch hunts. And while Folk City reveals an artistic and political movement steeped in nostalgia, it also shows evidence of the movement’s forward thinking, especially on issues like race. Among the objects on view are a photo of Lead Belly performing with white musicians in Lomax’s apartment and a Sing Out! cover with photos of the Selma, Alabama, civil rights protest.

“There’s strength in this music too, strength that made millions of bails of Southern cotton.”

But in the second and third sections of the exhibit that focus on the expansion of folk music culture—from the radical overtones of the organization People’s Songs, founded to “create, promote, and distribute songs of labor and the American people,” to a mass appeal that peaked in the mid-1960s—one can see a ’30s-style populism percolating subtly. In the black-and-white Hear Your Banjo Play short, Seeger tells an off-screen Lomax that he’s trying to revive folk music because “it’s very much alive for millions of people…. There’s strength in this music too, strength that made millions of bails of Southern cotton.” As the camera pans the New York skyline, doleful-looking, working-class New Yorkers appear, and Seeger cheerfully remarks that “the people in this big town are starting to like my music, too.”

Seeger and Lomax, calling “howdy” and “mighty” as they exalt the work songs of elderly yokels, would seem like patrician hucksters trying to cull plebian votes if they weren’t so in love with plebeian music. Though this doesn’t come through in the exhibit, the left-wing tendency to sanctify the masses also worked to keep the music plain and sometimes stunted, in order to preserve its associations with proletarian purity. And as I wandered the show, I wondered: What is appealing about proudly simple songs to those millions of Americans who aren’t inclined to romanticize the grandmother in the Blue Ridge Mountains singing, “The cuckoo is a pretty bird”?

By the 1950s, many of the next generation had begun to grow tired of music they associated with their parents. Younger people wanted to move, shake, act. They wanted sex appeal without shame. Other than a paragraph in the final “1964-Present” section of the exhibit on how the “British Invasion” brought guitar amps to the Village, Folk City doesn’t acknowledge the cultural tidal wave of rock ’n’ roll that the folk revivalists faced in the ’50s and ’60s.

I can’t imagine the urban intelligentsia around Izzy Young’s Folklore Center and Lomax’s Sing Out! pushing Appalachian ballads on small record labels and tiny Greenwich Village clubs after 1957. The absence of rock ’n’ roll in Folk City feels tantamount to laying the blame for the folk revival’s decline on McCarthyism and conservatism. Though the revival’s most successful act, the Weavers, was disbanded because of the hearings, the second Red Scare had largely petered out years before commercial rock took over the airwaves.

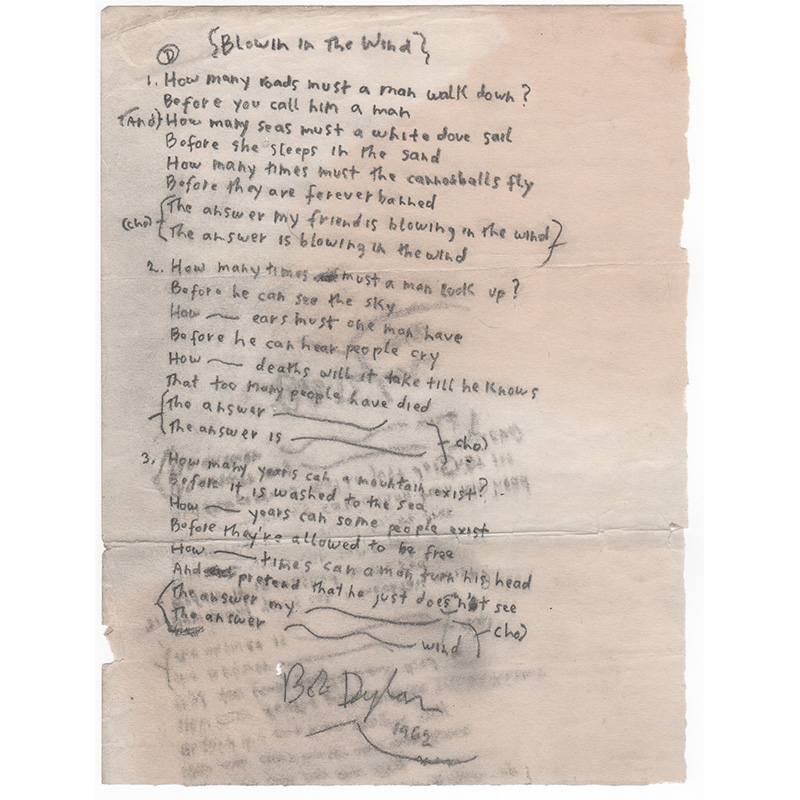

Only in the mid-’60s, when the revival’s most famous apostate, Bob Dylan, released the rock-infused Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, hailed by critic Greil Marcus as “the most intense outbreaks of twentieth-century modernism,” did folk music break new and exciting artistic ground. Dylan’s original handwritten lyrics to “Blowin in the Wind,” “Masters of War,” and “Maggie’s Farm” are, indeed, the stars of Folk City.

But read the last line of “Maggie’s Farm,” scribbled in a slanted and asymmetrical stanza across aging parchment: “They say sing while you slave and I just get bored.” Dylan seemed to be saying that folk music couldn’t save the world and could in fact be awfully boring. Ultimately, he chose to step off Fourth Street, plug in, amp up. “Masters of War” didn’t halt the carpet-bombing of Vietnam, just as Guthrie’s guitar didn’t kill fascists and the Almanac Singers didn’t spare the unions their slow decline.

It is hard to contemplate that the music so many of us hold dear was in some sense subsumed by a culture now dominated by Kanye. The folk revival was not only a serious and passionate attempt at holding up non-commercial, radical DIY art but also a movement that attempted to upend the status quo through song. Leaving Folk City, I came upon a photo of Woody Guthrie belting out a tune with his “This Machine Kills Fascists” guitar on a New York subway full of suits and hats, his eyes closed and his head tilted back. It reminded me that even if the music ran up against limitations, even if we cannot know what concrete changes it effected, even if “Blood on the Leaves” is far better known than “Strange Fruit,” we ought to celebrate the courage required to sing out.

Justin Slaughter is a writer and journalist in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Talking Points Memo, Salon, and The Brooklyn Rail.

To contact Guernica or Justin Slaughter, please write here.