Are American readers insular, as the secretary of the Swedish Academy famously quipped? If so, why has immigrant fiction taken such a pivotal role in American letters? Novelist Irina Reyn hashes it out with lauded Bosnian author Aleksandar Hemon, on the release of his Best European Fiction.

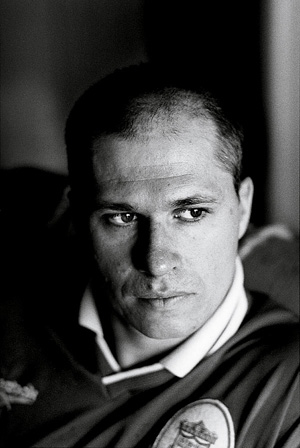

“The U.S. is too isolated, too insular… [they] don’t really participate in the big dialogue of literature,” said Horace Engdahl, secretary of the Nobel Prize-granting Swedish Academy, in 2008. It was an incendiary statement, and absurd not least of all because the rise of immigrant literature in America over the last thirty years has been, in my view, one of the more exciting developments in contemporary letters. “You can say that American publishing is insular, but readers are not necessarily so,” argues Aleksandar Hemon, editor of the recently published Best European Fiction 2010 (Dalkey Archive), a collection of short stories by thirty-five writers from thirty countries. And in many ways, Bosnian-American writer Hemon—whose body of work includes his debut The Question of Bruno, the National Book Award-nominated novel The Lazarus Project, and the short story collection Love and Obstacles—is the ideal refutation to the Nobel Committee’s assessment of our literary provincialism.

“The U.S. is too isolated, too insular… [they] don’t really participate in the big dialogue of literature,” said Horace Engdahl, secretary of the Nobel Prize-granting Swedish Academy, in 2008. It was an incendiary statement, and absurd not least of all because the rise of immigrant literature in America over the last thirty years has been, in my view, one of the more exciting developments in contemporary letters. “You can say that American publishing is insular, but readers are not necessarily so,” argues Aleksandar Hemon, editor of the recently published Best European Fiction 2010 (Dalkey Archive), a collection of short stories by thirty-five writers from thirty countries. And in many ways, Bosnian-American writer Hemon—whose body of work includes his debut The Question of Bruno, the National Book Award-nominated novel The Lazarus Project, and the short story collection Love and Obstacles—is the ideal refutation to the Nobel Committee’s assessment of our literary provincialism.

Born in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1964, Hemon came to the United States twenty-eight years later, in 1992, on what was originally a month-long cultural exchange program. Once the war in Bosnia broke out, he stayed, training himself how to write in English while working at a host of jobs including teaching ESL to Russian immigrants and canvassing for Greenpeace. His arrival coincided with the beginnings of the wide use of the Internet and the feverish flow of information, transportation, and communication that completely changed the parameters that had previously defined the immigrant experience. In contrast, when I came to the United States in 1981—a Russian immigrant before the age of globalization, at the tail end of the Cold War—immigration was a strictly one-way ticket, and my fellow writers seemed consumed by their efforts to navigate questions of assimilation, the uneasy straddling of public and private spheres. Today, Hemon still writes a column for a Sarajevo newspaper, returns to Sarajevo from Chicago often to catch up with family and friends, and, paradoxically, is more in touch with many of his Bosnian readers by writing in the English language. His fiction, in form and content, seems to cross and even erase national boundaries.

In this interview on the future of fiction, conducted in September as part of the University of Pittsburgh’s Contemporary Writers Series, Hemon speaks of never feeling cut off from Bosnia, of being “everywhere,” of happily juggling multiple identities, and feeling confident in employing and manipulating the English language to his will, creating out of it something familiar but changed. “We saw the thin stocking of smoke on the horizon-thread, then the ship itself, getting bigger, slightly slanted sideways, like a child’s drawing,” he writes in one of his early short stories, “Islands,” published in 1998. Have we ever envisioned an arriving vessel in terms of stockings and threads and the drawings of children before?

Immigrant writers have always melded their own meter and rhythm with those of English, but Hemon’s work showcases something unusually bold and expansive along these lines. Is it a marker of Hemon’s remarkable talent, his singular temperament? Is it fueled by the knowledge that questions of “home” no longer need to be negotiated in the same all-or-nothing way characteristic of earlier immigrant writers? Either way, the result—the prose, the ideas, the risks visible behind every word Hemon chooses—is always exhilarating.

Hemon—he prefers to be called Sasha—and I spent much of that day together, so the conversation we had on-stage was an extension of several hours of lively discussion on the future of the book as object, the way immigrant writing is reshaping American letters and the different relations we have with our respective home countries. It was remarkable how many Bosnians introduced themselves to the author before the event, so when Hemon later says, “I’m in touch with Bosnia in many ways, not just that I go back, but because I’m connected to the diaspora,” that bond was certainly evident that night.

—Irina Reyn for Guernica

Guernica: You’ve said that you consider yourself a citizen of two countries. You do not see yourself as working in exile because you are connected to your homeland. Since the notion of a global writer is a relatively new one, I’m wondering what you think the literary benefits or consequences of this position might be.

Aleksandar Hemon: Well exile, as you pointed out, is not the word I would apply to myself because I’m not cut off from where I came from. I’m in touch with Bosnia in many ways, not just that I go back, but because I’m connected to the diaspora. I also participate in the American cultural and political space: from playing soccer in Chicago to voting in the American election to participating in American literature. Whereas people who may describe themselves as being in exile are nowhere, I’m actually in two places at the same time, which is different. Despite what my characters feel and do in my books, I don’t feel so metaphysically displaced that I’m nowhere. Actually, the way my life has been in the last couple of years, I feel I’m all over the place.

Guernica: In the past, immigrant writing has been concerned with the question of assimilation and hyphenated identity. What’s happening now, and it seems to me that you’re at the cutting edge of that, is a different kind of writer, the one who transcends national identity. Do you feel like you belong in this group?

Aleksandar Hemon: I think if there is a group, it’s still forming, because people are still coming in. It’s a continuous process. When you say global writer, I think of Dan Brown who publishes his book simultaneously in various places and everyone reads the book, and that’s the end of global interaction. I don’t operate simultaneously all over the world, I operate simultaneously in Bosnia and America. As much as I would like that to be the whole world, it’s not. [laughs]

For some reason I was never afraid to use the English language. I have an accent and I mangle words anyway. I don’t care if I’m exposed as a bad writer.

What I think I may be typical of is a multiple identity situation. Assimilation is not an issue for me; I feel sufficiently assimilated in the United States. I’m not completely absorbed, I have not melted into the pot. My cultural instincts are satisfied by American culture. And the same thing with Bosnia. I am an American and Bosnian writer and I like to think that what happens in my books and in my life is that those two spaces overlap. They overlap through the experience of immigration and diaspora, and they also overlap because I want them to overlap—I write about people who are finding ways to live in the States because their life is defined by their Bosnian experience.

So this multiplicity of identities or double identities, these are not necessarily mutually exclusive and they don’t create a vacuum but rather create an overlapping space where interesting things happen. This is what defines what I write and defines the other members of who you might include in that group.

Guernica: You write in English but you also write a column in a Bosnian magazine. You said once that writing in English paradoxically allowed you to connect with Bosnians around the world.

Aleksandar Hemon: While waiting for this event to start, I met a couple of Bosnians who I haven’t known before and we quickly established contact. But wherever I go I meet people including friends that I’ve lost touch with. Because of my presence on the Web, people have tracked me down. I became a public person because of my writing in the English language and people who have read my books translated from English can then track me down.

Guernica: A lot of people who write about your work, always note your inventive, rich and unusual use of the English language.

Aleksandar Hemon: All lies. [laughs]

Guernica: But I find that because English is not my first language, constructing each sentence is extremely laborious for me as a writer. And in many ways this helps me see language anew. I’m wondering if you think immigrant writers have a leg up on native speakers as writers in the way they can see anew or even vampirize the English language to serve their purposes.

I met a guy in St. Louis who, when he got nostalgic, would get on the Web and watch snow fall in Sarajevo.

Aleksandar Hemon: You may have a case there, but I think it comes down to an individual sensibility. I write in Bosnian and I like to think that I have the same sensibility in Bosnian. I contort words in Bosnian, dismantle idioms and clichés compulsively. And I do it in English. I see no difference in my attitude toward the language. The difference might be there but I—temperamentally—might do it anyway.

Immigrants might not have the awe of the tradition of language. If you grow up in the language on the one hand, you’ve been exposed to it a long time, but real writers can see through that whether they’re native speakers or not. For some reason I was never afraid to use the English language. I have an accent and I mangle words anyway, so I don’t care if I’m exposed as a bad writer.

Guernica: So unlike myself—because I came to the U.S. in 1981—you are definitely a refugee of the Internet age, which is a big difference between our immigration experiences. How do you think technology altered or complicated the concept of home and displacement?

Aleksandar Hemon: Well, it’s too early to tell. I think technology has a neutral value at best; it could be used for good things or bad things. I think it fundamentally changes the situation of assimilation or participation in society. Because you can stay in touch daily with wherever you came from and you can listen to live broadcasts of radio stations or the prayers from the mosques or read daily newspapers, complete with obituaries online. I met a guy in St. Louis, a city that has the largest Bosnian population [in America], who, when he got nostalgic would get on the Web and watch snow fall in Sarajevo.

Ellis Island immigrants, on the other hand, would come in, work hard, be exploited, make it or not make it but even those who made it would go back thirty to forty years later to the village of their origin and they would find that one or two people remembered them. So it was easy to sever connections, and in some ways it was natural: your life was here, your old life was there. But I know a large number of Bosnians in Chicago who send their kids to Bosnia over the summer—school’s over, they send them to Grandma. These kids are bilingual, bicultural. Displacement is not necessarily political. You can go back and forth. Transportation has become relatively cheap. Masses of people are moving around the world: immigrants, refugees, labor migrants. It’s an entirely different world.

Guernica: It’s so different than coming over, not speaking the language, assimilating, having a tormented relationship to your place of origin.

Aleksandar Hemon: I can imagine especially for you cut off from people in the Soviet Union. They didn’t really know what your life in America was like. You had to retell the past ten years of your life. When I go back, we basically just rehash the gossip.

Guernica: I remember how exciting it was to get the first phone call from there.

Aleksandar Hemon: A friend of mine from Sarajevo and I are writing a script in Bosnian. We have three-hour conferences over Skype.

Guernica: Speaking about your second novel, The Lazarus Project, you said that you hoped to establish a continuity of human experience, that life in say 1908 is not so different than it is today. You also say that you need to tell stories about people that would otherwise be forgotten. The alternative, as you say, is silence. Can you talk about the writer’s role today in depicting history?

Aleksandar Hemon: I do believe in the inherent ability of literature to provide access to the knowledge of human experience that is not otherwise explored. What books can tell you about life or human beings. You can’t learn in any other way. In that sense, literature is a history of individual lives.

While history with a capital H is about great events, great leaders, or great processes, or great struggles, what literature can do is convey the incredible infinite complicatedness of an individual human life, the multitude of details that constitute human life. What literature does is it employs imagination and language to allow us to extend ourselves into other human beings. One might see it as empathy but I think it is well beyond that too. It’s an essential human activity.

The Lazarus Project is not a 9/11 novel. If I had to choose I’d rather call it an Abu Ghraib novel because the most painful thing to live through in the last administration was how we became complicit in the crimes the administration committed. It interested me how we were suddenly torturing people and taking photos of them.

The inherent democracy of literature, the multitude of human lives, is infinite in that regard and that includes the large parts of humanity that have suffered the most in history and those largely forgotten. I’m far more interested in people who would be forgotten because they never qualify by the standards of greatness that apply in capitalist societies.

Guernica: The Lazarus Project is widely seen as a post-9/11 novel, informed by a particular atmosphere. How is the current administration informing your present work?

Aleksandar Hemon: The Lazarus Project was not a 9/11 novel. If I had to choose I’d rather call it an Abu Ghraib novel because the most painful thing to live through in the last administration was how we became complicit in the crimes the administration committed. It interested me how we were suddenly torturing people and taking photos of them. I conceived of The Lazarus Project before the invasion of Iraq and before Abu Ghraib but then the picture of Lazarus being held up by the police captain—a dead immigrant that was suspected of something and killed just in case—was structurally identical to the Abu Ghraib pictures. I did not write a novel to pursue this. It was one of the lines of ethical, philosophical, narrative inquiry in the book.

Guernica: Your latest book, Love and Obstacles, is a collection of short stories. As a writer of both novels and short stories, you’ve somewhere said you prefer short stories if partly for their marginalized status in American literature. At the risk of depressing us, what do you see as the future of the short story, of the book? Where do you see it going?

Aleksandar Hemon: Short stories do not sell, this is something people in the publishing industry in New York widely believe and they don’t like writers to write short story books even after successful novels. My first book was a book of short stories and I refused to promise that my second book would be a novel.

But I think the short story has been revived by these so-called immigrant writers; they do not know what the common lore is so they don’t care about it.

As far as the future of the book as an object, we’re in the middle of a transformation because of the digitalization process—we talked earlier about the Kindle and the kind of dent it can put in the publishing industry. But I do believe that literature and storytelling has a safe future. The medium is still being negotiated, but I believe that we evolutionarily developed to speak and use language, and as an extension of that I think there is an inherent need for human beings to tell stories and also to hear stories or perceive stories. As long as there’s language, I think the future of literature is safe.

To contact Guernica or Aleksandar Hemon, please write here.