It was Firas’s fifty-fourth birthday and he was fasting. Salma was at it in the kitchen dressed in a t-shirt and an apron, stuffing squashes and rubbing meats with herb oils. The whole thing was almost more than he could bear. What a wife. He’d really scored with this one.

His ex-wife, Elaine, could never make a meal that elaborate. He had tried to teach her so many times that it became a joke. Entire vineyards must have been laid to waste in Elaine’s attempts at mastering stuffed grape leaves. Her dishes always had something off about them, like mustard in the lamb meatballs. Who the hell puts mustard in the lamb meatballs? How did she even think of that? But back then, he could care less. Elaine could have stuffed the leaves with dog food and he’d have said, Nice try, baby, let’s go grab sushi. He had loved every inch of Elaine: her long, honey hair, her sea-foam eyes, her creamy skin. Firas remembered standing on this very balcony, staring at the laundry-strewn rooftops and fantasizing about women like Elaine. Like those he had seen in his sister’s French Vogues when they were kids: Brigitte Bardot, or Jane Fonda. He’d prayed to God every day to grant him a woman like that. Looking out past the domes of St. Demiana, past the thousands of minarets, Firas had lifted his face up to the heavens and begged Him to pull him out of the muck of Cairo and deliver him to the West.

The hunger pangs were kicking in. It’d been a long time since he’d bothered to fast. He pinched prayer beads between his fingers but he wasn’t reciting anything. It was dusty hot and he was thirsty. He wanted water. He also wanted to pin Salma up against the wardrobe like he’d done the other night, when the electricity went out and they lit an oil lamp, but that was a no-go until sunset. What an idiot he was to fast. Though Salma was impressed with this turn of pious self-restraint. He flicked the prayer beads. She was really coming around in the bedroom.

A loud crackle from the kitchen snapped him out of his head. Whatever caused it made the whole apartment smell like garlic and grease. He left the balcony and leaned against the doorframe of the kitchen. As his wife stooped over the oven, he could see the lines of her underwear.

“Nice outfit.”

“What?”

“You know I’m fasting.”

“This old t-shirt?”

“I can see everything.” He came close and smelled her neck. She moved in closer to him but he intercepted her embrace, caught her wrists tight in his hands.

“That’s not very nice,” he said.

“I’ll put on something else,” she whispered.

“Don’t bother,” he said. Firas dropped his prayer beads and grabbed his wallet. He had to get out of there if he was going to make it fasting through the rest of day.

Outside, he walked at a quick clip, passed a donkey-pulled cart full of gas tanks. The vendor’s pitch bounced off the buildings. Firas salaamed him. He was good at all the salaaming. He didn’t have a destination in mind but made a right into the main thoroughfare. The traffic was disgusting, worse than Los Angeles. A small beaten Fiat jammed itself up over a corner and onto the sidewalk for an extra foot, nicking Firas in his thigh. Fumes from the exhaust rose like smoke signals. Firas pounded his fists against the passenger seat window. “Asshole!” he yelled. “Son of a bitch!” He remembered he wasn’t supposed to swear while fasting, either. The guilt made him even angrier.

Cairo was a mess. They could’ve stayed in Saudi Arabia or Dubai during the revolution, set up a pretty good shop, but Salma had insisted. It was 26-year-old, bleeding-heart thinking, but what could he do? He was in love.

Firas left the Fiat in the mess of gridlock. He passed a pet store stacked with animal cages, one with a monkey in it. His daughter Sarah had loved playing with the monkeys. She had been in her terrible twos when Elaine had dragged them to Cairo, but it was Firas who kicked and screamed. First and last time, he’d sworn, but now here he was, back.

He saw some kids poke their fingers in the cage but the monkey was unresponsive. He’d been sitting there too long with no takers. For a split second, Firas imagined buying Sarah the monkey. He saw it hopping around her small off-campus apartment, messing with the seltzer machine she kept on the counter. It made him smile, but adult Sarah didn’t like pets.

The mosque across from Effendi’s looked decent, like it might have newish ceiling fans. That was key.

Firas cut down an alleyway, thinking he’d go to a mosque. At least there temptation would be at a minimum. He could hide out until sundown, even get some actual praying done. Salma would be impressed he spent the day at the mosque. So he ducked into a side street, and saw a legless man eating a banana. Firas pulled out his wallet. He only had Saudi riyals and American dollars left. To atone for the swearing, Firas gave him a twenty. The legless man looked at him, annoyed.

“Thanks, America. I’ll go walk into a bank and exchange this right away with my two excellent legs.”

“Hey, man, I just got to town.”

“How nice for you, already on a walking tour.”

Firas flushed. He reached his hand out for the money. “Don’t let me burden you,” he said. But the legless man stuffed the bill in his waistband.

The mosque across from Effendi’s looked decent, like it might have newish ceiling fans. That was key. Firas went around and entered from the back, to take off his shoes in the vestibule. It was off time for prayer, so not too crowded. A man entered the vestibule to grab his shoes on the way out. Firas had a funny feeling, like he’d seen him before. Something about his round face and soft stare.

It was Magdy.

Firas couldn’t believe it. He’d gained weight, more than Firas ever had. And he wore traditional Egyptian clothing, a long white tunic. He used to wear nothing but jeans. But Firas hadn’t seen him since high school, when they were in a band together, playing covers of “Hound Dog” and “Wild Thing.” Since their lucrative days hawking loosies and Cokes to the pilgrims flocking to St. Demiana.

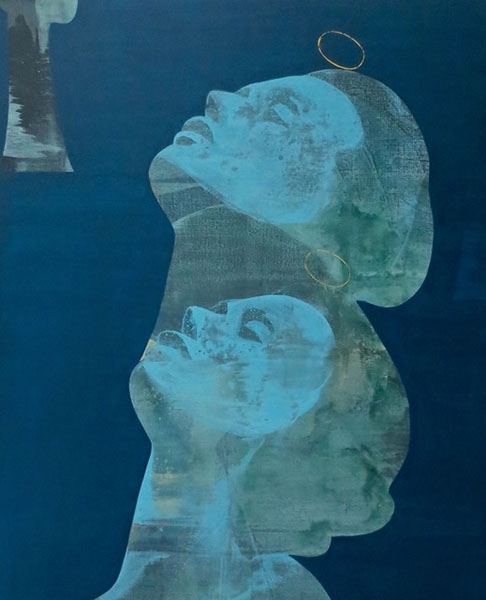

Those strange and magical days started in April 1968, with the first appearance of the Marian apparitions. Farouk the bus mechanic saw her first, a hazy figure at the top of the domes, a white-hot light. He panicked, afraid the woman intended to jump to her death. Farouk was easily unnerved, but this time a crowd gathered with him, distraught. Police arrived and dispersed the onlookers, waving them away with claims that it was just a streetlamp reflection, an errant moonbeam. But then it happened again days later, and every few days for the following three years. The Blessed Virgin was settling in with the people of Zeitoun, revealing herself to those who were patient enough to wait. People from all walks of life came to see Her, Muslims and Christians alike, tourists, journalists, scholars. It was international news. When crowds overwhelmed the streets and public safety became an issue, the government intervened and blocked off a section of Zeitoun, charging entrance fees and additional costs for creature comforts like folding chairs. Sighting the Virgin Mary became a government-sanctioned Egyptian pastime, and Firas and Magdy fueled the sport with nicotine and Coca-Cola.

But it was when the miracles started happening that business really surged. People came through in droves. Egyptians had been so miserable after the epic defeat of the Six-Day War, and then all of a sudden the country was united, Muslims and Copts together experiencing fertility fixes or whatever it was they needed, all with a quick glimpse of Our Lady. Even President Nasser acknowledged Her, like a good omen for his March 30 Manifesto. So many dreams coming true in that time, from ’68 to ’71, all you had to do was ask.

Firas asked and asked.

He couldn’t remember exactly when it all started, his dream of going west. It came slowly, eleven-twelve-thirteen, Coca-Cola-television-sex, so it felt like they were always there. For as long as he could remember, everyone had begrudgingly admired the West: the wealth, the scientific and technological advancements, the unabashedly beautiful women. It was everyone’s bitter secret, this admiration, this uncompromised reality that the West was leading the world and leaving them in its moondust. But such moral depravity, moaned the adults, the parents who hovered in Firas’s peripheral vision when they had to be tolerated. Firas couldn’t have cared less about what they thought; the West was the future and he would be part of the future. Cairo was ancient history—had been ancient history since ancient history. He despised his countrymen, hanging on to the glories of mummies, selling stupid miniatures of pharaohs and sphinxes at every corner. The same Khan-el-Khalili that he would later take Elaine to with pride (the gold is the finest, the rugs are the best!) he loathed in his adolescence. It reeked a musky stench of stagnation, despair, third-world death.

And then Europeans came through to see the apparitions. It was the first time Firas had seen Westerners in Zeitoun. Of course, he’d seen them in typical tourist spots all his life: at the pyramids, in the bazaars, along the Nile. But never so close to home. Two beautiful Dutch girls came through one late summer evening, tall college students with backpacks. They already had Coke bottles, but Firas was smitten and offered them free cigarettes. They accepted, carnation-pink lips stretched wide over white teeth. Then there was a flash of light, and there She was, a voluptuous burst of light hovering between the domes. Firas had seen it before, but never so clearly, so insistently present. He never doubted that these things could happen; signs of God’s presence were everywhere, and no one he knew had ever questioned that. But to be there, in the glow of the divine spectacle, in the warmth of fresh faith, Firas was swept up in the miracle and prayed again to God to grant him his greatest wish.

Many times afterwards, even in the beds of American women, Firas would relive that time in the vacant ground-floor apartment.

The boys brought the girls to an empty apartment in Firas’s building, which his parents owned. On some old woolen blankets that he had stashed in a closet for such occasions (high enough up so his mother would be too short to find them), smelling of tobacco, he made love for the first time to a Western woman. The differences were intoxicating: the ivory skin against his brown, the pale eyes, the soft blonde hairs that covered her body. But the personality, too, was wondrously divergent from that of the bitter Egyptian girls he’d seduced; those girls always insisted on darkness, always exhaled shame. Hadn’t they? Marinka, on the other hand, pushed her shoulders back and opened her chest, her desire for pleasure echoed clear in her barefaced laugh. Many times afterwards, even in the beds of American women, Firas would relive that time in the vacant ground-floor apartment.

Three years later, Firas had driven his mother so crazy with incessant rock ‘n’ roll and screaming fits of rage that she finally agreed to send him to art school in London, just to get him out of her house. She wanted to be left in peace with her angelic younger son, Kamaal. Kamaal was going into pre-med at Cairo University, and would live at home, and play his mother her favorite songs on the oud whenever he wasn’t too busy studying.

As he packed up his duffel bag before heading to the airport, Firas heard the metallic chime of the church bells of St. Demiana, quickly drowned out by a million muezzins calling to him, reminding him to pray. He dropped to his knees and threw his forehead on the ground, and although the tears didn’t fall, his thanks flowed out of him like a river. If his mother hadn’t pulled him up off of the floor and dragged him to the car, yelling, “Lord, get this devil out of my house!” he would have missed his flight. He didn’t step foot again in al-Zeitoun until he was there with Elaine and Sarah, playing with monkeys.

“Magdy?” He gave Firas a puzzled look. Then the recognition flushed his face. “Son of a bitch!”

They got touchy in the Egyptian way, unafraid to kiss and reach out for flesh. Firas noticed Magdy had a couple gold teeth and many brown ones. It made him run his tongue over his own pristine whites. Which reminded him: he needed to check the pharmacy for whitening strips. Salma could use some of those.

“Kamaal told me you were coming! When the hell did you get here?”

They chatted for a few minutes, feeling each other out. It felt good, falling into an old rhythm. It gave them energy.

“Blushing groom, I hear?” Magdy teased.

“Something like that,” Firas said.

“Listen, what’re you doing?” Magdy asked. “My wife’s away. I’ll pull out the shisha.”

Firas considered his options. Technically, he wasn’t supposed to smoke anything while fasting, but he wanted to hang out with Magdy. He could just refrain from inhaling. He caught a whiff of the stale-feet smell of the mosque. Saw the ceiling fans were not newish.

“Let’s go,” Firas said. He hadn’t even gotten around to taking off his shoes.

They walked down a residential street much like Firas’s. Housekeepers in colorful hijabs were beating the dust out of old rugs with sturdy brooms. Campaign posters were everywhere, a few as high as ten feet, with some stern-looking brothers staring you down. His brother, Kamaal, he’d probably vote for the man who’d end up winning, whoever that might be. Firas wondered what their mother would have made of the revolution. Probably not much; to her, it had all become meaningless after they killed Sadat.

Magdy stopped in front of a modest building and unlocked the gate. They crept to the back and climbed up precarious stairs. Magdy was ahead of him and Firas noticed the leather strap of Magdy’s left sandal was broken, exposing a calloused heel. They passed through a porch busy with toys and household wares. Herbs grew in clay pots along the ledge.

Magdy pointed to the mess of toys and smiled, “Grandchildren.”

Inside it was dark. They went to a small room in the back with a couch and a table: Magdy’s man cave. It smelled like a thousand and one nights of shisha. At least that explained the brown teeth.

While Magdy prepped the pipe, Firas used the bathroom. His urine was dark from dehydration. He checked his watch: still three hours until sunset. If he smoked, it’d make him thirstier. He’d deserve that.

The room grew smoky quickly. The bright orange coals were muted by ash.

“I’m so glad you’re here for the voting,” began Magdy, sucking hard on the shisha nipple. “Proud time to be an Egyptian.”

Firas watched the smoke spiral upwards from Magdy’s mouth, to the ceiling. It looked like dancing ghosts. He wondered if Magdy did anything with his free time other than smoke.

“You ever play guitar anymore?” Firas asked.

Magdy shook his head. “The devil can have it,” he said. “Such a time suck.” He tested out the shisha, exhaled, and passed the nozzle over to Firas.

It was now or never. Really, fasting was about the food and the sex. Those were the biggies. He wasn’t touching those.

He took a puff.

It tasted like tobacco and mangoes.

“Flavored? Really?”

“What? I love mango,” Magdy said. Firas felt the buzz of the nicotine and grew lightheaded.

“I’m leaning toward the Freedom and Justice Party.”

“The Muslim Brotherhood?” Firas was surprised.

“They’re different now! Moderate, like the Turks. Did you know their veep is a Copt?”

Firas stared blankly.

“Well, he is. And there’s nothing wrong with a little more attention to social morality. I don’t want my grandkids growing up in a world where you can run wild and everyone thinks it’s OK.”

Magdy went on talking about different party candidates, thoughts, conjectures. Firas rested his head on the back of the sofa, lost in the smoke. He wondered what that meant: a world where you can run wild. Did he think that was the kind of world they grew up in? Did he think there was a way to keep kids from skipping Friday prayer and smoking hashish in the backrooms of cafés, as they had done? Or in the broken-down buses in the mechanic’s yard? He thought about the time he and Magdy went into El-Batiniya themselves, hadn’t just scored the stuff through a friend of a friend. He could see the faces of the young boys standing in the alleyways, their eagerness flickering in and out of visibility with the shadows, their husky voices pushy and urgent, some just cracking on the cusp of pubescence. On others he could smell the City of the Dead, the unmistakable, rancid odor of those born and bred in a tomb. Metallic. Those kids were the lucky ones; they didn’t have to hustle the shirts off the backs of fresh corpses at the Friday market. They got to sling oil.

Oil!

Top quality oil!

You must try my oil!

Hey, big guy, right here, the best oil!

“Oil,” Firas said.

“What?”

“Remember? They used to call hashish ‘oil.’”

“That’s right.”

“You got any?”

“Damn,” Magdy said, looking at Firas straight. “You’ve been here an hour and already you wanna start trouble?”

“No trouble.”

“My God, are you addicted?”

“It’s been ages.”

“Then why?”

“For old times.”

“I don’t approve of this anymore, you know.”

“No one’s asking for your approval.”

Firas wondered if Magdy was afraid smoking hash with him would make him feel old, or young, or both.

At least that made Magdy grin. He gave his mustache a few good strokes as he thought about it. It was a mustache to be proud of, thick and still black, unlike his hair. Firas wondered if Magdy was afraid smoking hash with him would make him feel old, or young, or both. Firas was feeling both. He saw the lines break around Magdy’s eyes and felt old, but then heard him laugh, say “son of a bitch!”, and felt like he was sixteen again.

“I bet your son has,” Firas said.

“I don’t think so.”

“All kids smoke.”

The son’s room was as expected: dirty clothes, a computer, a sexy poster.

“Who’s that?” Firas asked.

“Haifa Wehbe. Hot Lebanese piece.”

“Wow.”

“Yeah. He should really take that down.”

“Never.”

“I’m taking it down,” Magdy said as Firas snooped through a dresser drawer. “He needs to get serious.” Magdy picked at the tape that held up the poster, careful so it wouldn’t tear.

“Your son is boring,” Firas said. “I don’t even see any dirty magazines.”

“Yeah? What about your son?”

“My son. Hmm.”

Firas looked under the bed. There were three boxes. The first held a cache of letters. The second box, a lot of fancy cigarette packs. The third was promising, just a pair of dress shoes. Firas reached his hand inside to the right, and then the left.

Jackpot.

Magdy was still working on the last piece of poster tape. Firas peered into the packed shoes. Each one loaded with hash. Holy shit, Firas thought. The kid is a dealer.

“My son, I dunno. He doesn’t talk to me,” Firas said. He grabbed a finger of hash and moved it into a cigarette pack from the second box. He put the pack in his pocket. Put the shoes away.

“That’s sad, Firas. That type of thing is common in the States, isn’t it?”

“Huh?”

“A son needs his father’s guidance. How old is he now?”

“I think twenty-two?”

“Four years older than Emad.”

“Look, I have a confession,” Firas said.

Magdy was rolling up the poster.

“What?”

“I have hash on me. I forgot.”

“You forgot?”

“I haven’t eaten all day, I’m not thinking straight.”

Magdy set the poster down and took Firas by the shoulders in earnest.

“Now I’m really concerned about you, Firas.”

“I’m fine, really.”

“You’re addicted, aren’t you?”

“I swear to God I’m not. Some guy sold it to me in the street; I forgot I had it in these pants. I thought it’d be fun.”

“I don’t think it’s a good idea now.”

“Come on. Everyone smokes every now and then.”

“Not everyone,” Magdy said. Feeling smug about his son.

“Don’t make me smoke alone.”

Magdy shook his head. He said, “Just so I can look after you.”

They went back to the man cave.

Firas settled in an armchair while Magdy sat on the couch, closer to the cookies he’d brought out.

“What’re you gonna do with Haifa?” Firas asked.

“I’ll talk to him. He’ll listen.”

Magdy put the hash in the shisha pipe for convenience. As they started up Firas noticed all the family photos on the wall. There were Magdy’s daughters and grandkids, nice enough, and a boy he assumed was Emad. He looked a lot like Magdy. He spent a long time on the portraits of Magdy’s wife. A couple of her young and slender with curly hair, then recent ones of her stout and covered up. Elaine would never have let that happen. She was a Pilates maven. This woman, she had thick, grooved hands from all the housekeeping. The cost of keeping it together on her husband’s slim teacher’s salary, Firas guessed.

“Where’s your wife?”

“Amina? Alexandria for two weeks. With Yasmeen and the grandkids.”

Firas coughed a lot. He hadn’t smoked in over twenty years. Elaine had ended that party when Sarah came along. Magdy, on the other hand, didn’t seem to have any respiratory difficulties.

“Old times,” Magdy said.

Firas looked at the photographs of Amina again and this time thought about Salma. Smooth, olive skin. Hair that fell down her back in thick waves. What a fool he’d been when he was young to think that kind of beauty was second-rate. He took a long puff and a prayer popped in his head.

I seek refuge in God from agitation and sorrow.

It was what people said for heartbreak and such.

He took another long drag, smooth, and exhaled a serpentine stream of smoke. It belly danced in front of him and he thought of the caterpillar in Alice in Wonderland, floating on that mushroom and smoking endlessly. Lena had been the caterpillar for Halloween one year, when Sarah was Alice. Firas held the smoke in his lungs until it burst out of him. Magdy was saying, “Shura, Elelaimy, Salafis,” but Firas was fixated on the smoke, which had started to form the caterpillar’s mantra:

“WHO

R

U?”

He wasn’t at Christmas. He would never be at Christmas again. His children were at Elaine’s parents’ two-story Tudor in Connecticut for the holidays, opening up piles of presents, baking cookies, building snowmen. He wasn’t being dragged through the slaughterhouses of Macy’s, Bloomie’s, Toys R Us. He would never again stay up all night on Christmas Eve, building a pyramid out of the presents so tall that the Christmas tree beside it looked puny. He had been as bad as the trinket-sellers in Khan-el-Khalili.

He had worked so hard; would they ever give him any credit, or did that all go out the window because he left? Elaine would never have to work a day in her life. Wasn’t that worth something? It didn’t make up for some of the things Firas had done toward the end, but it was something.

The smoky letters were twisting into Arabic. This kept happening to Firas, the English breaking from his head like a fever, ever since he married Salma. When did his thoughts start to slip back into his mother tongue?

Allahumma inni authu bikka min al-hammi wal hathan.

He hadn’t meant to do some of those things; they just happened, like it had been someone else doing them.

Like the time they drove Sarah out to Yale and he got sick, and they were holed up at Elaine’s parents’ place for a week, his world nothing but a dark bedroom and the muffled melodies of classical and country drifting up from the kitchen.

He didn’t eat for four days, and when he finally could, all he wanted was his mother’s saffron-chicken soup, with its spicy root vegetables and shredded white meat. They brought him Campbell’s Classic Chicken Noodle and he swallowed every last drop. Then he took a long, hot shower, put on some clean cotton clothes, took a compass from Greg’s fishing box in the basement, and went outside in the backyard.

Firas left his shoes on the mat by the screen door and laid the compass on the flat ridge of a birdbath. He tweaked the needle, 59.4 degrees from north, and unrolled a large towel onto the freshly cut grass, right in front of a bush of red flowers. Firas brought his bare feet together at the edge of the towel, raised his hands up to his ears, and then placed the right over the left just below his sternum, beginning his prayer.

He heard the screen door slam and then Ann said, “He must really like those azaleas.”

Elaine waited until she was reinforced by the intimacy of bedtime. Why did he have to make a scene? Why couldn’t he have prayed in the bedroom, like a normal person? Her whispers cut into him and his chest tightened with anger. But when he turned to face her, he saw her pale eyes blurry with tears, and it struck him that she was crying because she would never be the good daughter. He loved her so much in that moment that it was painful; the excruciating love for a woman for whom he’d dedicated his whole life. And so he scooped her into his arms, taking hold of the flesh-and-blood girl from the photographs in his sister’s French Vogues.

I’m sorry, Elaine, I loved you, I loved you so much.

He woke Magdy up with his coughing. Magdy acted fast for someone so stoned, brought him a giant glass of water.

Magdy looked at Firas and this time Firas knew he was really seeing him. He was imagining what he’d look like if he’d been the one to go.

“Bottled!” Firas croaked.

“What?”

“I need bottled water, I can’t drink the tap.”

“What the hell! I don’t have bottled, man.”

“Juice!”

Magdy got juice. Firas never wanted juice so badly. He brought it to his lips like a dying person.

He spat it back out. “Shit.”

“What now?”

“I can’t. I’m fasting.”

Magdy looked at Firas and this time Firas knew he was really seeing him. Saw his designer polo shirt and pressed slacks and clipped nose hairs. He was imagining what he’d look like if he’d been the one to go.

They went up to the roof to watch the sunset. St. Demiana was visible. So was the moon, and a few of the brighter stars. Finally, Cairo erupted into a staggered chorus of men’s voices. The day was officially over.

Magdy heard the phone ring downstairs and went to answer it, leaving Firas alone with the sky. Firas remembered the big birthday feast that awaited him back at his apartment and that he was ravenous. He turned in the other direction to see if he could find his apartment, but the smog had crept up thick. He needed to break his fast. He would ask Magdy if he had dates and milk. Who didn’t have dates and milk?

But just as Firas turned to go, his eyes swept up and he saw Her, the great Virgin, hovering between the church domes. He saw Her turn to him and open Her arms.

“Magdy! Magdy! Magdy!”

Magdy ran up. “What is it, old man?”

Firas pointed at St. Demiana.

“There!”

But when he looked again, his eyes focused and everything became clear, and he saw that it was just a light.