When we breathe, air glides into our nose or mouth, down our larynx and trachea, and into our lungs, where it nuzzles into air sacs. Oxygen, carried by the air, passes through our thin lung walls to enter into the bloodstream and circulate the body, conjoining with sugars to produce energy, braiding into proteins to build new cells, and, if the body has been wounded, combining these efforts to promote healing. Following an injury, oxygen is forced away from the wound, crowded out by white blood cells that inflame the area as they huddle together, cleaning and clearing the site. After disinfection is done, oxygen returns to the wound on the backs of red blood cells to build replacement tissue and complete the recovery process — or that’s what happens during healthy healing. If a wound’s inflammation lasts too long or is too pervasive, it can suffocate the tissue, killing off a portion of the body.

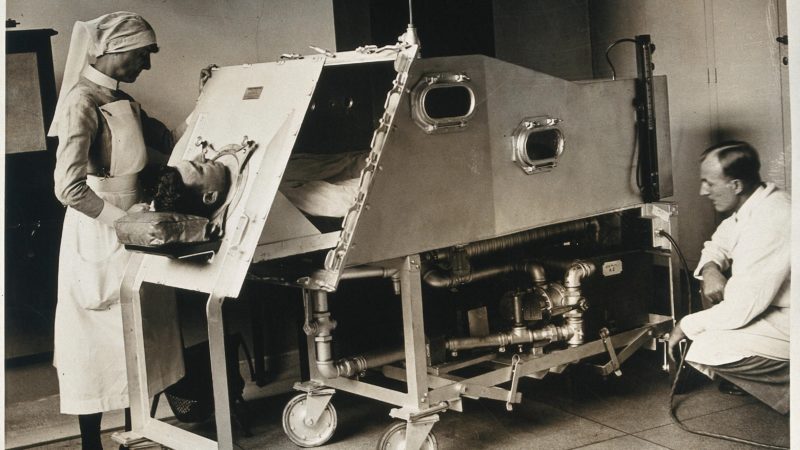

For chronic wounds with extensive inflammation, hyperbaric oxygen chambers revitalize the body by applying pure oxygen in a pressurized environment, keeping wounded parts alive. The chamber’s increased air pressure reduces inflammation, allowing oxygen to return to the suffocated wound, while the pure oxygen that patients breathe increases its availability for the final wound-healing stages.

My father was a doctor and director of our state capital’s wound healing center. As a child, I visited him at work, dazzled by the real-life science fiction novel he inhabited. Entering one of these chambers is like stepping inside a submerged submarine. Fluorescent light bends around its curved metal walls, and silver pipes outline the ceiling. Small portholes reveal the sterilized hospital room outside, a still-life behind a thick pane of glass: the sink, tongue depressors, an open box of rubber gloves. The chamber is a room inside a room. The seats are cushioned, but the space isn’t comfortable. The air pinches a little tighter, the pressure pushes a little harder, and there’s only one thing to do: put on an oxygen hood, a transparent deep-sea diver’s helmet, and breathe.

Consider this case study, which I discovered in my father’s old files. A patient had diabetes, which strangled feelings in their lower extremities, meaning they couldn’t feel the pain alerting them to injury. When they suffered a deep gash in their foot, blood flowed for a year, drenching socks and gauze. But after spending roughly an hour a day in the chamber for six weeks, the foot completely healed. New skin covered what had been a trench of open flesh. Before the last-ditch effort of the chamber, an amputation had been scheduled. Now, the patient’s foot was whole. This case of healing isn’t an aberration. Hyperbaric oxygen chambers may sound suspicious, or superstitious, but, for intensive wound healing, they work miracles.

There’s one problem. Pure oxygen feeds flames. In 2009, a four-year-old child named Francesco Martinisi entered a hyperbaric oxygen chamber with his grandmother by his side. A static electric spark, like the quiet crackle from a pulled-off wool sweater, ignited the oxygen, and the room erupted into fire. For five minutes, the two burned to death, trapped inside the chamber. Thirteen years earlier, a patient inside a chamber felt cold and shook a chemical hand-warmer, which set fire to his synthetic blanket. The ends of the chamber blew off, killing the patient’s wife, and, hours later, the patient. In 1987, a child rolled an electric toy inside a chamber, and eight people died. A patient who lit a cigarette killed four others. An electrical cord combusted in a chamber, incinerating four people. Between 1923 and 1996, there were thirty-five fires in hyperbaric oxygen chambers and seventy-seven deaths.

Cruelly, these chambers excel at healing severe burns. While the chance of fire is small, the consequences are catastrophic. Oxygen, that small, simple molecule that surrounds and sustains us, is never one thing: it harms us and heals us, it kills and it saves, and these incompatible truths abide, constant but invisible. Take a deep breath. It’s there.