From the air, Rwanda’s hills look ageless and impenetrable, much the same as they must have appeared in 1994. Beginning that April and lasting into the summer, the people who lived on those hills rose up in violence against one another, the culmination of a half-century of unrest between the Tutsi and Hutu ethnic groups. In a hundred days, on a patch of land smaller than Massachusetts, more than half a million people were murdered by their neighbors. It is impossible to think that trauma of this magnitude would not have left a mark.

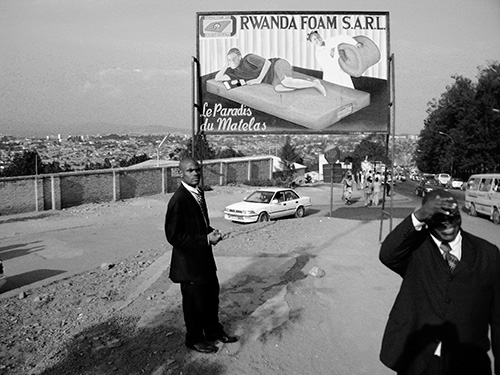

My first impression of Kigali is of orderliness. Police stand guard in the city center supervising traffic; motorcyclist-taxis wear uniforms and carry helmets for themselves and their passengers. Window glass of new hotels and offices glitters in the equatorial sun, and garbage piles that one customarily finds in poor countries are nowhere to be seen. It is hard to imagine that fifteen years ago this city was a war zone. In a country with such a dark past, there is a simple logic to concentrating on looking forward.

Exploring beyond the capital, it quickly becomes apparent that the countryside is not as untouched as it seemed from the air. Hills are quilted with fields of banana trees, coffee, and tea, a patchwork of neat seams and vivid colors. Rwanda is the most densely populated country in Africa, and all of the arable land seems to be under cultivation, one plot running right up to the next.

Soldiers are everywhere still. They exude relaxed confidence. When this army overran the country in 1994 and ended the genocide, much of their success was attributed to the strength and discipline of the troops. But to maintain security since then, the new government relied on establishing strict control over information. It outlawed ethnic categories, banned the teaching of national history, and closed independent newspapers and radio stations. Watching these men, I wonder if the appearance of concord will be sufficient to eventually produce an authentic peace.

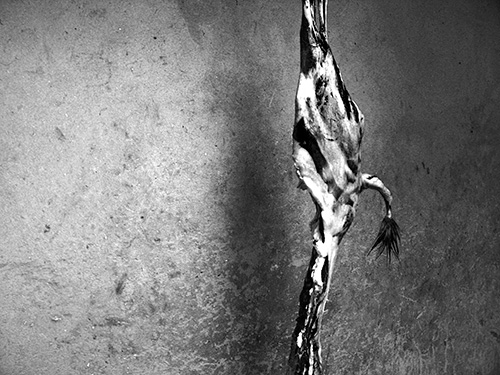

The genocide was perpetrated by victims’ neighbors and kinsmen, often with hoes or machetes — the tools of daily life in Rwanda. Today, many survivors continue to share the same communities with those who once pursued them. And in the everyday chores of trimming a lawn or carving a piece of meat, the old weapons repeat the motions of the past. Trying to leave memory behind, they cross paths with it at every step. There is something futile about trying to forget violence that was so ordinary.

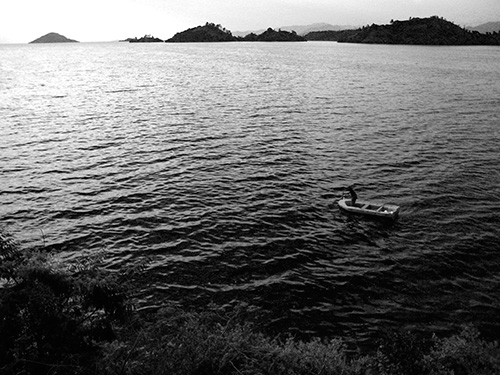

Surfaces are deceptive. The placid waters of Lake Kivu extend across the southwestern corner of the country. Countless bodies lie beneath its waves, dumped there by their killers or sinking with exhaustion in desperate but impossible attempts at escape. The genocide reached its apex in this region, where nine of every ten Tutsis were exterminated. For anyone ignorant of this fact, it must be one of the most beautiful areas of the country.

Cries echo over the crowd at Amahoro Stadium in Kigali, as two popular soccer clubs prepare for a match. During the genocide, the meager United Nations peacekeeping forces established headquarters here; thousands of Rwandans sought precarious refuge within its walls to wait out the siege occurring in the city beyond. The stadium is the biggest public building in the country, so it also serves as the main stage for the national commemoration ceremony held each year in April. The Rwandan calendar now revolves around such collective rituals of remembrance.

There is an old elephant named Mutware who lives in Akagera National Park east of Kigali. He too endured the war, I was told, and it was during this time that he lost one of his tusks. The human conflict, it was said, transformed the once-gentle animal to a violent and unpredictable misanthrope. He spends most of his time now alone and brooding, erupting occasionally into strange furies; after he destroyed three cars in the park in 2005, the US State Department issued a warning about visiting him. But his wildness has only made him more interesting, and tourists at the park never depart without first trying to see him.

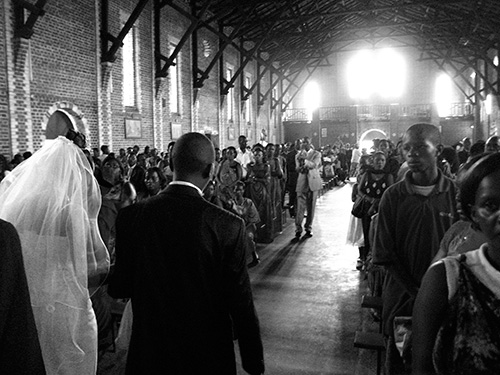

The churches of Rwanda were not spared from violence. Here, in Kigali’s massive Sainte Famille cathedral, Tutsis who sought refuge during the genocide were given up to the militias by their clerical protectors. Elsewhere, groups made their last stands in churchyards against mobs of antagonists. I met one Rwandan, confident since childhood that he would join the priesthood, who had quit the seminary after the genocide, unable to retain his faith. But most Rwandans did not lose their need for holy spaces; indeed, they have re-inhabited them with a new fervor.

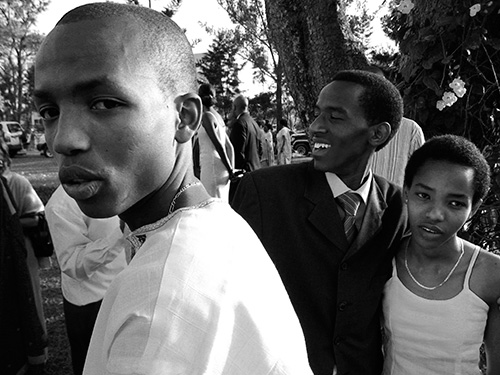

On some days, several weddings are conducted in parallel, their parties crowding the nave together. A chamber where death once hung in the air is filled with singing and fresh promises. Afterward, receptions spread out across the lawns of the hotels around town.

Rwandans speak expressively with their eyes, and have a vast range of ocular gestures. Unlike Kinyarwandan, whose undulating tones my mouth did not seem adapted to produce, this language is one with which I am immediately comfortable. Even as I find myself exchanging winks or raised eyebrows with passersby in the street, though, I am uncertain of the meaning we are conveying to one another. No one talks openly about the past here, and I am left wondering if a sharp look or a rough gesture hides something more dangerous behind it.

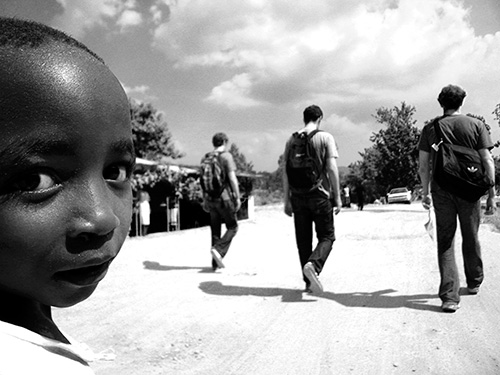

Even as they grapple with their history, the vast majority of Rwandans must also face the immediate challenges of abject poverty. One way of conceiving of development is as an expansion of individual capabilities, be it in the realm of education, employment, or political participation. Perhaps because their lives have been touched so deeply by their national history, in ways that are so apparently beyond their individual control, I visualize this process in Rwanda as one of authorship. Rwandans, like people everywhere, want and deserve to control the narratives of their own lives.

More than half of Rwandans are under nineteen now, too young to remember the genocide themselves. But a fifth of these children are orphans; for them, history is not a presence in their lives so much as an absence. It is difficult to say what legacy this generation will inherit, what stories they will grow up to inhabit themselves.

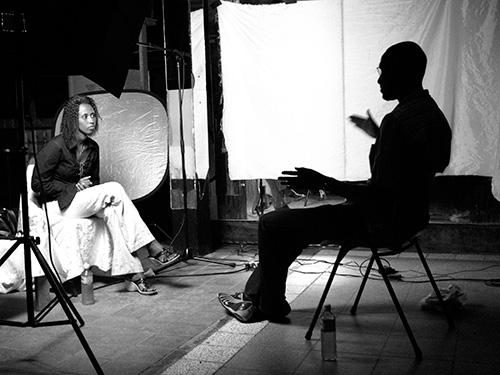

Some organizations have taken it upon themselves to protect the past, convinced that a true understanding of one’s history is vital to constructing a meaningful future. Voices Of Rwanda, among others, is busy recording and preserving video testimonies across the country. Through a global electronic archive, they hope to share these narratives with both Rwandans and other people around the world, and to inspire a global sense of responsibility to prevent human rights atrocities in the future.

Having left Rwanda, I find it difficult to retain in my memories the reality of the place. To preserve a concrete knowledge of what Rwandans have experienced, without allowing it to dissolve into fragmented analogies and images, seems both imperative and impossible. History haunts the landscape of Rwanda. But like all phantoms, it is elusive, nebulous, intangible.

Ted Alcorn received his BFA in Film & Television Production from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, and following graduation, he worked on Ken Burns’s documentary miniseries The War. He made the accompanying photographs while in Rwanda filming for the Voices Of Rwanda testimony archive. He is currently a Gates Foundation Fellow in international public health and international policy at the Johns Hopkins University.

Recommended Reading:

We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda by Philip Gourevitch