Years ago, I sat in the polished office of the notorious Guatemala City attorney Fernando “Skippy” Linares Beltranena alongside my best friend, Juan Carlos Llorca. At the time, Llorca worked as Guatemala City bureau chief for the Associated Press. He knew the ins and outs of every government system, and he was helping me as I reported a book investigating organized crime and corruption in adoption.

Our days consisted of tracking down people like “the lady who sold chicken on that street corner six years ago” and waiting outside certain government offices for hours to receive leaked files. We were scouring for the details we needed to describe and define Guatemala’s largest export industry in the years following 2004: sending children abroad via international adoption. Juan Carlos’s own research led to a stunning statistical analysis: one out of every one hundred babies born in Guatemala was exported for adoption, and nearly all of the adoptions were for-profit. It felt so dark. The players. The buyers. The sellers. Was everyone in on it? Why did no one act? Everyone knew about it, and it seemed like almost everyone wanted a piece of the pie.

The question seems simple: What are the best interests of a child? But it depends on who you ask.

At its height, the international adoption industry moved thousands of children each year, raking in millions in profit. It shut down fifteen years ago, after a variety of improprieties and fraud came to light. Since then, journalists and academics have attempted the mammoth task of unraveling what transpired. The modern, almost entirely privatized adoption system was a networked undertaking involving a cast of characters who oftentimes didn’t know each other. Even those intimately involved, those who comprised links in the chain — judges, adoptive parents, jaladoras and buscadoras, doctors, lawyers, agency owners, birth parents — couldn’t necessarily see or know what happened a few links behind or ahead, a design that offered the comfort of plausible deniability for those involved in criminal or coercive practices of family separation and rebuilding.

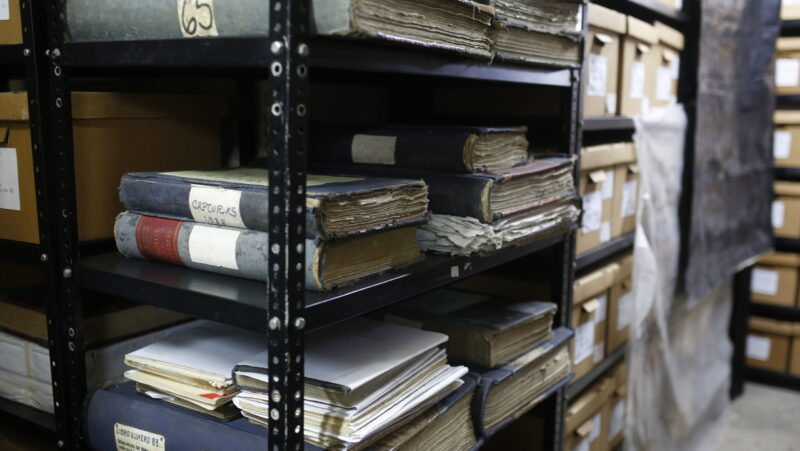

The most comprehensive effort yet comes from Rachel Nolan. In her graceful and expansive first book, Until I Find You: Disappeared Children and Coercive Adoptions in Guatemala, Nolan traces Guatemala’s adoption infrastructure backward through the decades using adoption files discovered inside storied national police archives from the thirty-six-year Guatemalan Civil War. The archive helped Nolan understand public adoption programs in Guatemala and how they changed after market privatization in the late 1970s. Her unprecedented work weaves together social and political context and masterfully lays out the most complete history of Guatemalan adoption we have.

Before, during, and directly after the Guatemalan Civil War, displaced minors and child victims of war crimes existed. What happened to them, told through Nolan’s sensitive and empathetic assessment, was a result of complicated decision-making around their “best interests.” Nolan offers a nuanced and authoritative portrait of a permissive and complicated landscape. Her book will continue to perplex and devastate, especially as those adopted to the Global North during the boom begin to come of age as adults, grappling with their own questions.

— Erin Siegal McIntyre for Guernica

Guernica: Is this a hopeful book?

Nolan: I love that as a place to start. Well, the subject matter of the book doesn’t seem that hopeful. But I do see the project, as a whole, as a hopeful project.

It is extraordinary that people in Guatemala are willing to give access to these kinds of files, even if it’s temporary. It is extraordinary that some of these stories, which were meant to be hidden, have come to light. It is extraordinary that there’s an activist movement around them. And it’s extraordinary that adoptees have found each other and gotten organized.

Adoptee associations are trying to find out more about the past, be it child trafficking for private adoptions or be it genocide-era forcible disappearances that resulted in adoption.

Guernica: You weave together texture and context around what eventually became one of Guatemala’s most significant export industries: babies and children. And yet you’re a historian of modern Latin America, with broad interests including political violence, civil and dirty wars, genocide, deportation histories, and foreign relations. What led you to focus on coercive adoptions?

Nolan: Like with most major research projects, I came into this one completely sideways. I had been working as a freelance journalist in my early twenties and lived in Mexico from 2010–2012. When I was doing a PhD in Latin American history [at NYU], I was casting around for a topic, as one does.

I came across material about the 1976 earthquake in Guatemala and learned that Pentecostal Christians were involved in adoptions, among other things. I found New York Times stories from 2006 talking about this extraordinary boom in adoptions there, and one statistic drew me in: one in one hundred children from Guatemala was adopted internationally. I thought, Wait, that can’t be true. There must be a mistake. How can that be? How is it possible?

The first book I picked up was yours — Finding Fernanda. I was utterly scandalized by the lack of structure in Guatemala. What I learned from your book and through later research was that what I thought must be illegal practices — coercion, even theft of children — well, they were actually legal under Guatemala’s very permissive governmental structure at that time.

That led me to more questions. What happened to forcibly disappeared children during the civil war?

I learned of the existence of the [Guatemalan government’s] adoption files by reading Paper Cadavers by Kirsten Weld, which is about the National Police Archives in Guatemala City. Kirsten had a note on one page saying that one of the many types of documentation that the archivists at the National Police Archives were scanning were adoption files — because they held evidence of war crimes and legal abuses.

And I thought, Oh my God, the adoption files exist. They’re accessible.

That’s why I started.

Guernica: How did you decide who to talk to, and what was your experience like?

Nolan: There is a cultural stereotype about Guatemalans that they are very quiet. Although cliché is always just cliché, there’s a grain of truth there. It’s a widely acknowledged phenomenon that people in Guatemala are not so ready to share their life stories, especially to outsiders, given the abuses of the thirty-six-year civil war. It takes repeat visits and building up what in Spanish is called a sense of confianza. It’s not just confidence but trust and reciprocity, in some cases, to get people to be willing to talk about some of the more difficult parts of their lives.

I was shocked that adoption lawyers wanted to talk to me, the lawyers who had previously overseen private adoptions. They were annoyed that adoptions had been closed in 2008; they thought they’d been unfairly demonized. And they were happy to talk to an outsider.

My status as a white North American made it much easier, in many cases, to do interviews in Guatemala. There’s a certain kind of status afforded to outsiders. Certain lawyers from elite circles probably thought, Oh, this is someone from a university who’s white. I can justify myself to her; maybe she’ll go back to North America and make the case for reopening international adoptions. (They will be very disappointed in my book!)

Birth mothers are an incomplete piece of the story because I didn’t think it was right to intrude on their lives. I had a lot of their contact information from the adoption files, but I figured early on that it was totally unethical to try to contact women cold. That was because, in many cases, they’d given up children for adoption in secret or under pressure. They may be newly partnered with someone who doesn’t know about that past, or they could be subject to domestic violence. Instead, I tried to grasp their points of view when I could through other interviews, court records, and the adoption files themselves.

Guernica: One of your aims was to better understand “the confining social and economic structures within which Guatemalan women made choices.” What understanding do you come away with?

Nolan: Part of what I was trying to show was that what people think of as “consent” in a rich country is not the same thing as consent in an extremely impoverished, highly unequal country like Guatemala. Half of the population is Indigenous. People might speak one of twenty-two Mayan languages. And Guatemala has a long tradition of discrimination and dispossession that far predates the genocide. Indigenous people were targeted for genocide in the 1980s by a US-backed military government.

Even if you’re looking at cases of international adoption where children were not forcibly disappeared by the military, you still see women, especially poor women and often Indigenous women, under enormous pressure to relinquish children for international adoption. That pressure is not just coming from the government; the pressure might be coming from an overbearing father, from a misogynistic brother, from an abusive spouse.

Part of what I’m trying to show in the book, and the reason that I use the word coercive in the title, is that the conditions under which people in the United States and other wealthy countries would like to think international adoptions unfold are not always the real conditions. I wanted to make people aware of not just abuses like kidnappings and forcible disappearances but about forms of pressure or coercion that are not necessarily illegal.

Guernica: You describe the “roughly five sets of circumstances” for children that led to adoption. What are they, and how did you come to frame and define them?

Nolan: The first group were children forcibly disappeared during the civil war. Sometimes children who survived army massacres were put up for adoption within Guatemala and abroad. The social workers who ran the state program for adoptions were connected to the army.

A second set of circumstances was kidnapping. This is well known, in part because of your work and also because kidnappings caused scandals. As far as I can tell, this is an important but small subset. While it is a fact that many children were trafficked, and these cases are important to write about, the available evidence shows kidnappings were the smallest group.

A third set of circumstances were women forced to give their children up for adoption. You can read in the files that women were coerced into giving up children rather than relinquishing them freely. That’s a very large category.

A fourth group were the women whose children were willingly relinquished — consent, in the usual legal sense. This group might include Guatemalan women whose partners were working as migrant workers in the United States, and who became pregnant while their partners were gone. These women include those who could not have a child without facing serious consequences, like no more remittances being sent home, or domestic violence. These women likely saw relinquishing a child really as their best option. It opened a door and gave them a significant amount of freedom. But I’ll put an asterisk next to this group. Abortion is neither legal nor freely available in Guatemala. So even when I’m talking about meaningful consent given willingly, you still have to keep in mind the kind of misogynistic structures in the country.

The last, fifth category are children who were truly abandoned. A lot of people in the Global North think this is the vast majority of international adoptions: children who are found on the street, in a box, at an orphanage. I did find some of those cases, but they’re not the majority in Guatemala. They don’t even reach 10 percent. The journalist E. J. Graff uses that fabulous phrase “the lie we love” because people would like to think that they’re adopting purely abandoned children.

Guernica: Throughout the book, a steady, transparent amount of care is taken to prevent flattening the narrative threads into black and white, victim and perpetrator. This always matters in storytelling, but why does it matter specifically to a book about Guatemala and Guatemalan history?

Nolan: I think there’s a real temptation to narrate history in terms of bad guys and good guys. Calling out abuses either in the present for journalists or historically for historians — well, that’s important.

In Guatemala, because of the genocide, there can be a tendency outside the country to narrate the ladinos, the non-Indigenous people, as perpetrators and Maya Indigenous people as victims. It’s much more complex than that. It was important to me to say at the outset that there were Indigenous women working in the for-profit adoption system as jaladoras, effectively as baby brokers.

But that said, because of the unequal conditions in the country, most of the people who were making money from for-profit international adoptions were not Indigenous and were members of the elite.

Playing the blame game is not helpful. It’s very tempting to want to point fingers in a straightforward way, but one of the interesting things about being a historian is that you’re always trying to think about how people are living their lives and making choices in ways that are available to them — but always locked within a set of structures that they can’t necessarily control.

The work of a historian is not just to try to move readers to empathy across space and time but also to move ourselves into uncomfortable places or find empathy or understanding that we wouldn’t have had at the outset.

Guernica: I wanted to ask you briefly about the perspectives of the social workers. As a reader, it was captivating to glimpse the perspectives of some of the social workers who helped facilitate adoptions in the 1970s and ’80s, as they looked back.

Nolan: I work with a fabulous research assistant, Sylvia Mendez. She was a wizard at finding retired social workers.

Their concerns, at the time of their work, were practical. They weren’t asking, Why are there five children that the army has brought into an orphanage in Quetzaltenango? Instead, they were saying, Okay, we have five new children — we need to get enough money to feed them, beans, and rice. And we need three bottles of milk a day for them.

Talking to them, you could start to understand that, in wartime, they thought looking for family was not that practical. Neither was looking for the extended family of a child who’d ended up in an orphanage. You could see how they’d believe that the best-case scenario was to put children up for adoption in the United States. That sat uncomfortably with errors that I found in files, the erasure of details.

A theme of the book became how flexible the term “best interest of the child” can really be. Does it mean access to material wealth in the US? Does that mean access to a grandmother in an Indigenous family? It means something different to different groups. The tragedy here is that Indigenous communities were not getting their say.

Guernica: In a Harper’s podcast a few years back, you mentioned being surprised by how immersion in this research led to your deepening empathy and sympathy for adoptive families.

Nolan: One of the many things that adoption records contain are letters written by adoptive parents to orphanages or to private lawyers explaining the reasons that they wish to adopt. Only a stone could fail to be moved by some of those accounts. Long struggles with infertility. Children who had previously died. A sincere religious faith that I don’t share but nevertheless find deeply moving. Caring for the world’s least protected. A lot of these letters moved me.

That primed me to write about adoptions in a different way, where I was taking into consideration the constraints of adoptive families and their knowledge of what was happening on the ground in Guatemala. It’s not fair to expect every adoptive parent to be a historian of the Guatemalan Civil War, right?

That’s why we should have governmental structures — so that abuses don’t happen, so that well-meaning adoptive parents don’t fall into adopting children who really should not have been available for adoption.

Guernica: In the book, you mention that the US State Department may have wanted to quash your access to the adoption files at Guatemala’s Ministry of Social Welfare. Why?

Nolan: Someone told me that if I talk about this publicly, I’ll never have a Fulbright again.

Before I went to Guatemala, I was pulled aside at a Fulbright orientation and told that the US embassy in Guatemala had raised red flags about my project. While they didn’t try to prevent me from doing research with the adoption files, they asked me not to do it while in Guatemala on a Fulbright.

And I thought, This is crazy! I applied for the Fulbright requesting funding in order to read the adoption files. They gave me the funding. I’m going to go read the adoption files.

I think what they were concerned about is that the story does not reflect terribly well on the US government in Guatemala. And thanks to your efforts, we have all of the US embassy cables — all of the receipts — showing that the US government knew about abuses in the adoption scene in Guatemala well back into the 1980s, and it wasn’t until the 2000s that they did anything about it.

Guernica: Toward the end of the book, we’re left with the image of searching: young people seeking. Where are we today?

Nolan: We’re left with the first wave of Guatemalan adoptees, adopted mostly to Canada and Europe, who are in their midthirties and coming up on forty. Some have been searching for their families for a decade or more.

The first wave has found out about some of these difficult truths about falsified paperwork and where they came from. The second wave, the vast majority of kids adopted from the 1990s to closure in 2008, are still growing up in the United States.

But to be clear: Some adoptees never search. They aren’t interested in meeting [their] birth families. They do not want to know about the history of Guatemala. That is very understandable on a human level.

But many do. What I imagine is going to happen in the next few decades is that a huge number of people entering young adulthood, with access to their adoption paperwork, with the time and perhaps interest in searching — I imagine this story will be ongoing. And I am looking forward to learning from them.