To wander Manhattan is to step into the modern fulfillment of an earlier age. The hurtling traffic, the stylish storefronts and bars, the pyramids of cupcakes, the lantern light of iPhones—it may all seem dreadfully contemporary, but its antiquity lies in the time of steam. “New York is a product of the nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution,” Lewis Lapham observed in the fall 2010 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, “built on a standardized grid, conceived neither as a thing of beauty nor as an image of the cosmos, much less as an expression of man’s humanity to man, but as a shopping mall in which to perform the heroic feats of acquisition and consumption.”

If the lust to acquire and consume is one defining feature of the city, so too is its complement–deprivation and economic disparity. David Harvey, author of Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, describes Manhattan as “one vast gated community.” He describes the process by which the rich push the city’s less well-off to its peripheries and take hold of urban life. Tracing the history of urban uprisings from the 1870s to Occupy Wall Street, Harvey argues that cities have long been contested spaces, where the interests of money collide with the public good. Beginning in the late nineteenth-century—when modern New York took shape—one finds the dawning sense that for the city to be made safe for consumption and its contented, bourgeois destiny, it needed to be purged of the blemish of the poor.

For Industrial Revolution-era exponents of this belief, the spectacle of “acquisition and consumption” was one of arresting beauty. Were you to climb the spire of Trinity Church in lower Manhattan in 1872, you would have an uninterrupted view north along Broadway as far as Grace Church on Tenth Street. That vista, hemmed on both ends by Gothic steeples, offered a glimpse of the awesome scale of New York. Man shrank into the precision of the pumping city. “The long lines of passers and carriages take distinct shapes, and seem like immense black bands moving slowly in opposite directions,” wrote James D. McCabe, a nineteenth-century chronicler of the city. “The men seem like pigmies, and the horses like dogs. There is no confusion, however. The eye readily masses into one line all going in the same direction. Each one is hurrying on at the top of his speed, but from this lofty perch they all seem to be crawling at a snail’s pace.” Broadway had real power, absorbing the frantic striving of the individual into the rhythm of a city so much larger than him. It was, in McCabe’s words, “the most wonderful street in the universe,” dwarfing all other European or American rivals in “the extent of its grand display.” Broadway was “a world within itself.”

What sparkled in those two marvellous miles between the churches? What great display condensed the wonder of the universe into this single stretch of New York street?

Shops, of course. McCabe, the author of the guidebook Lights and Shadows of New York Life (1872), delighted in listing the proliferating stores that studded Broadway. There at the corner of Grand Street sat “the beautiful marble building occupied by the wholesale department of Lord & Taylor.” On Prince Street you would find “Ball & Black’s palatial jewelry store.” Passing theatres and hotels—the St. Nicholas, the Comique, the Metropolitan, the Olympic, and so on—you would finally reach “an immense iron structure painted white,” the vast edifice of A.T. Stewart’s Retail Store, one of the city’s first department stores, occupying the entire block between Ninth and Tenth streets. “It is always filled with ladies engaged in ‘shopping,’ and the streets around it are blocked with carriages. Throngs of elegantly and plainly dressed buyers pass in and out.”

McCabe dropped quotation marks around the word “shopping” because it was a novel activity. As a pastime (and not simply an exercise of necessity), shopping came into its own in the second half of the nineteenth century, when consumer-citizens, liberated by the mobility of the street car and the new safety offered by gas and electric street lamps, found disposable time and income to spend on the stuff of the industrial age. Shopping reflected the growing prosperity, elegance, and aspiration of New York. Broadway lay at its heart. “Jewels, silks, satins, laces, ribbons, household goods, silverware, toys, paintings… rare, costly, and beautiful objects of every description greet the gazer on every hand. All that is necessary for the comfort of life, all that ministers to luxury and taste, can be found here in the great thoroughfare.”

Manhattan has become a “gated community.”

On Broadway, “no unsuccessful man can remain in the street. Poverty and failure have no place there.” One finds in McCabe’s guidebook an early example of the very bourgeois faith that we are what we buy. Broadway was, in his view, much more than a street. As a triumphant expression of both progress and prosperity, the spectacle of consumption was the defining scene of the age.

Today’s New York, where the belief that you are what you buy has been taken to an absurd extreme, might be familiar to McCabe. According to the CUNY-based urban geographer David Harvey—a contemporary Marxist scholar of the city—the “quality of urban life has become a commodity.” Ambitious consumption in New York encourages the sort of vacuous pursuit of fashion that prompted Ian Schrager, a slick hotelier and developer, to write: “Nationality and class have been replaced by lifestyle.” The ideal New Yorker has no past and no background, only a wallet and a will to buy.

New York recedes for those without ample wallets and appetites. According to Harvey, Manhattan has become a “gated community.” In Rebel Cities, Harvey sketches a bleak picture of the modern city. New York, he explains, is only one example of a universal trend. Growing inequality splinters all the major metropolises of the world, separating the wealthy from the rest across social and geographic divides. Dispossession, as much as consumption, is the logic of the city; the general public has a diminishing stake in urban activity and increasingly remote access to urban life. A tireless hunger drives this process onward. Harvey argues that since the Industrial Revolution, cities have been the principal site where capitalism sustains itself, used by financiers and developers to “absorb surplus capital.”

Writing in 1872, the genteel McCabe would never have used or even considered this language. But the New York he envisioned foreshadowed the city it would become.

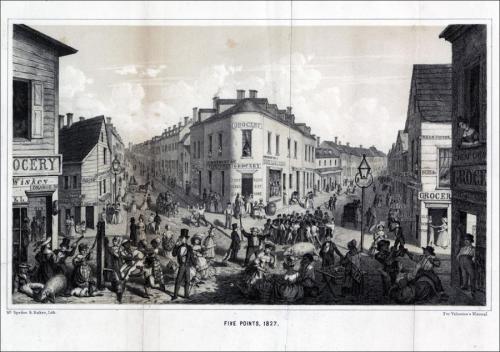

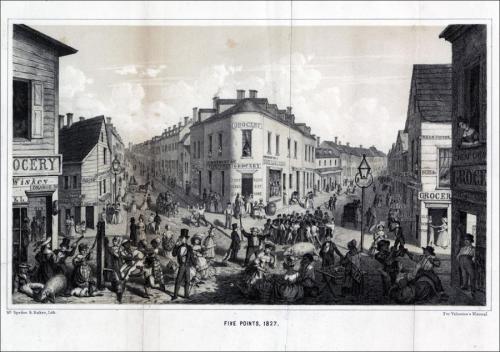

Away from Broadway’s storefronts, the uptown dames in their carriages, and the gas glow of the marquee, the city was a far darker place. McCabe mustered the courage to explore the less fashionable regions of the city (many of which were “within pistol shot” of Broadway), but not by himself. He only ventured into “terrible and wretched” districts like the Five Points and the Bowery in the company of police officers. “No respectable person can with safety visit them, unless provided with a similar protection.”

What was particularly galling for McCabe was the closeness of poverty and destitution to polite wealth. Since the late nineteenth century, writers have described New York as a city unique in the density of its contrasts, its landscape of extreme differences. One could stand in the Five Points, at the intersection of Park and Worth streets, “in the midst of a wide sea of sin and suffering, and gaze right into Broadway with its marble palaces of trade… and its roar and bustle so indicative of wealth and prosperity.” The narrow gap between the two worlds was one that “the wretched, shabby, dirty creatures who go slouching by you may never cross.” McCabe journeyed to the Five Points in part to achieve some measure of authority as a guide to the city, but Christian pity also directed his creeping adventures. He praised the efforts of various missionary and church groups bent on cultivating order in the benighted parts of the city. Their work formed the only bridge between the “realm of poverty” and that of virtuous money—realms that lived so near and yet apart. But he despaired for their Sisyphean struggle: new waves of migrants always poured in, encrusting the slums with desperate activity and equally desperate idle.

Yet even in their differences, the denizens of the Bowery found a kind of solidarity perceptible to an outsider like McCabe. “They are all ‘of the people’. There is no aristocracy in the Bowery.”

McCabe marvelled that such “misery” could fester right beside Broadway’s march into a future of happy consumption. The city lost its efficient grid only blocks away from the stately avenue, narrowing into a warren of ragged slums, home to sprawling families and one-room shacks, sweaty life on the pavement, and a honeycomb of murkier tunnels beneath. “It is a strange land to you who have known nothing but the upper and better quarters of the city.” There is a fevered quality to his descriptions of the Five Points and the nearby Bowery. “Decency and morality soon fade away here,” he wrote. “Drunkenness is the general rule.” Bands of street musicians haunted the ramshackle squares with “discordant strains.” From the cellar saloons rushed the sounds of “fearful revelry” and “hot foul air,” which carried the promise of vice and disease “inhale[d]… with every breath.”

Much of Lights and Shadows does not consist of these explorations of New York’s teeming slums. McCabe was more interested in describing streets like Broadway, the city’s grand buildings, celebrity businessmen and media moguls, and the various gradations of society among the well-to-do (he sneers at those families who added a “van” to their names to affect membership in New York’s ancient Dutch class, the Knickerbockers). But when he enters the Five Points or the Bowery or the wharves or other cramped, scruffy parts of the city, his writing becomes repetitive, a litany of heinous deeds and miserable creatures all bound by his hopeful belief in their Christian redemption.

I try to imagine him, flanked by stocky policemen, as he strode through the Five Points: a gentleman with notebook in hand, regarding the inhabitants of that quarter as if they were inmates in a prison, or beasts in a zoo. And I like to think that some of those “wretched, shabby, dirty creatures who go slouching by” may have occasionally stopped slouching, straightened, and looked him in the eye.

The people of the impoverished regions of New York City unnerved McCabe, and through him, his readers across the country. “Every tongue is spoken here,” McCabe wrote of the Bowery, by “men from all quarters of the globe, nearly all retaining their native manner and habits, all very little Americanized.” These included “the piratical looking Spaniard,” “the gypsy-like Italian,” “the chattering Frenchman,” “the brutish looking Mexican,” and “the sad and silent ‘Heathen Chinee.’” Yet even in their differences, the denizens of the Bowery found a kind of solidarity perceptible to an outsider like McCabe. “They are all ‘of the people’. There is no aristocracy in the Bowery.” A danger lurked in this rough egalitarianism of the slums, a danger beyond the usual peril of pickpockets, knives in the dark, drunkenness, and riotous blasphemy. Much more worryingly, the motley poor all seemed to boast a seditious streak, to wear, as McCabe observes with alarm, the “irresistible smack of the Commune.”

McCabe published his guidebook a year after the Paris Commune of 1871. For over sixty days, the working classes of Paris seized the city and seceded from France. Informed by various strains of leftist politics, the Commune implemented a range of measures radical for their time, many of which would still be considered radical today.

The New York press was shocked by the sweeping implications of the Commune’s actions, like the strict separation of church from state, the empowerment of women, and the restructuring of commercial relations, which in sum amounted to a cavalier assault on the establishment. It demonstrated to a writer for Harper’s that the French were “ignorant, angry… and inflamed by crude theories.” Particular bile was reserved for the many women who played prominent roles in the defense of the Commune. Harper’s accused what were known as the “Amazons of the Seine” of being “coarse, brawny, unwomanly, and degraded” and “ten times more cruel and unreasonable” than the male communards. The New York Herald described female participants as “debased and debauched creatures, the very outcasts of society.” From the perspective of moneyed New York, the Commune inverted the moral universe, plunging Paris into the frenzied dystopia of the unwashed masses.

What was the gleaming vision proposed by Broadway if it could be so ignored, even overshadowed, by the darkness nearby?

Mingled glee and relief greeted the demise of the Commune when, two months later, the Prussian-backed forces of Versailles broke through and slaughtered tens of thousands of people—rebels and civilians alike—in retaking the city. Harper’s crowed: “The effort of the Commune ends, therefore, without the least sympathy or respect.” The Nation claimed in an editorial that “it would be difficult to produce from history an expression of selfishness narrower or more material, more short-sighted and more devilish in its intensity, than the organization which has just perished in the flames of Paris.” There were a few dissenting opinions, including those of observers who had seen the achievements and struggles of the “communards” with their own eyes, but these were swallowed in the overwhelming tide of contempt for the Commune.

The eruption of the Commune in Paris shook New York’s chattering class, and for good reason. Every day and around every corner, New Yorkers saw the contradiction of life in their own big city—that treacherous slip of space between wealth and poverty. There was no real hinterland in New York, no world of remote existence totally obscured from the bourgeois gaze; slums like the Five Points, after all, leaked into the side streets of Broadway. The wealthy often supported the work of religious missions not simply out of Christian charity, but to stave off the threat of rebellion at home.

Like many of his peers, McCabe found offense (and threat) in the coexistence of these two worlds, in how life in the Five Points lurched on wholly indifferent to the prosperity and refinement of the grand avenue. Where Broadway ran wide and straight, the Five Points dissolved into a series of dark turns. Where the former boasted department stores and other shrines to the new cult of consumption, the latter belched with the excess of another kind of public life: beer gardens, bawds, beggars, and street bands, days and nights spent quietly and loudly in the open. As McCabe saw it, the poorer parts of the city smouldered with an “air of unrest.” What was the gleaming vision proposed by Broadway if it could be so ignored, even overshadowed, by the darkness nearby?

Paris in the mid-nineteenth century had proposed its own solution to this problem. In the decades preceding the Commune, Paris underwent a drastic overhaul now known as “Haussmannization,” named after its architect, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. The gnarled medieval core was levelled to make way for a network of wide boulevards, neat parks, and orderly buildings, the new “city of light.” Haussmann’s Paris was cleaner, more efficient, and ostensibly easier to control; the demolished warrens of alleys and irregular streets had long offered sanctuary to urban rebels. It was also more expensive. Rents rose precipitously, and working class people found themselves expelled to the outer arrondissements on the periphery of the capital.

A more stratified, utilitarian city, however, was not immune to rebellion. According to David Harvey, the Paris Commune was in part a response to the project of Haussmannization, to the alienation of the poor from their own city. Harvey argues that the rebellion of the Commune in 1871 was one of the first expressions of the “right to the city,” of people reclaiming urban space as their own. Barricades blocked Haussmann’s boulevards. Local councils organized the provisioning and defense of each neighborhood. The Commune may have collapsed in bloody defeat, but it became, for social theorists and activists, a model of political mobilization in the city.

In Rebel Cities, Harvey draws a winding line from the barricades of Paris to the 2011 occupation of Zuccotti Park, a tiny square on Broadway near Trinity Church. Harvey describes both the efforts of the Commune and those of Occupy Wall Street, however short-lived, as struggles over the meaning of the city: Who should have access to the city? What is the purpose of public space? Should only the doyens of the market have the power to decide the structure of urban life? Or should, in some fashion, the rest of us?

These questions were as present in the 1870s as they are now. In McCabe’s view, the city had two faces. One was exemplified by Broadway, with its gleaming shops thronged by elegant customers. Consumption made it a marvellous place. The other New York lay in the slums of the poorer neighborhoods, like the Five Points and the Bowery. Nothing redeemed this side of the city. It condemned itself through its strangeness, its cantankerous squalor, its queer heterodox life, the primordial rhythms of its debauchery and struggle. And it occupied prime real estate that would be better used, borrowing Harvey’s jargon, “mopping up the surpluses of capital,” that is, in being developed to produce greater value for owners and investors. McCabe notes approvingly the astronomic rise of the price of a building bought and renovated by a Christian mission in the Five Points. The neighborhood needed wholesale change. As far as he was concerned, New York was not big enough for two New Yorks.

Slum clearances levelled most of the Five Points by the end of the nineteenth century. Fifty years later, Robert Moses—New York’s answer to Haussmann—in his own words “took a meat axe” to many parts of the city after World War II. Inequality both in the United States and in New York City widened sharply since the late 1970s when the country turned to the right, away from modestly redistributive, social democratic municipal politics. The 1990s witnessed Rudy Giuliani’s crusade against panhandlers, prostitutes, and the scruffy poor. Real estate prices soared in post-9/11 New York, and even after the recession, huge tracts of the city remain inaccessible to many of their former inhabitants.

Like Paris, New York has largely banished its poor to its extremities. Economic inequality long existed in Manhattan, but its staggering scale (the top 1% of the city earn 44% of its income) is new, as is the stark geographic division of its regions of wealth from those of comparative poverty. For most of the history of the city, rich and poor areas abutted each other with relative frequency. No longer. New York has its hinterlands now. It is almost impossible for a humble middle class, never mind working class, family to live anywhere south of 125th Street, or to settle west of the Lower East Side projects on the East River.

The process we through gritted teeth call “gentrification”—but should rename dispossession—has long preoccupied Marxist thought. A robust skepticism of “urban renewal” and attempts at “modernisation” runs through Harvey’s work. In the name of public health or beautification, people are relieved of their homes and their livelihoods, only to be shunted further from the life of the city and to find themselves in conditions often no better, if not altogether worse, than those from which they came. Harvey quotes Friedrich Engels on Haussmannization: “The scandalous alleys disappear to the accompaniment of lavish self-praise by the bourgeoisie… but they appear again immediately somewhere else… the breeding places of disease, the infamous holes and cellars in which the capitalist mode of production confines our workers night after night are not abolished; they are merely shifted elsewhere!”

You don’t have to subscribe to the gospels of the left to see the continuing truth of Engels’ observation. What happened to the Five Points is all the more visible in cities in countries like India. For the sake of building a “better city” (and of capitalizing on land and property prices), slum clearances scattered the poor from the flyovers to make way for shopping malls, chrome offices and high-rise apartment complexes. Which in turn, in their increasingly distant, panting remove from the air-conditioned world of the middle class the poor can never hope to access.

No one should be envied for living in slums and favelas. But the impetus to clear them is only thinly moral. For the wealthy, slums are an an embarrassment, an inconvenience, or a source of dread. They seem to be an aberration in the urban scheme. In our modern cities, the poor should be kept out of sight and, worse, out of mind.

Urban life should require the awareness and experience of the difference of others. Much has been written about the demise of truly shared public spaces in cities. Privatization and commercialization, pollution, policing measures, and the growth of the internet all encouraged the public to retreat from their streets and squares. Urban planners in the metropolises of the “global south” routinely overlook public space altogether, building cities out of knotted highways, shopping centres, and high walls. Public spaces of course exist in New York, but they are often strictly manicured or quixotically regulated or, like the High Line, simply spaces to pass through, not assemble in. The city at all times steers its residents and visitors towards consumption. The smartphone has only encouraged this: New York becomes a place of destinations, not paths; replicable activities, not experiences; a map of amusements to be pinned and tagged rather than a city to be known and unknown.

McCabe, roaming the city in the 1870s, was horrified by the entrenched poorer neighborhoods and their ramshackle village-like public life, for which there was no bar to admission. Enamoured with Broadway and its stores, he found no value in the egalitarian clutter of the Five Points. Today’s New York is a vindication of McCabe’s preferences, it is a city where consumption reigns supreme. All other forms of public existence shrink: parks shut every evening with grim discipline, benches vanish from the avenues, the working poor—let alone young people or the homeless—have little room in a New York so thoroughly mediated by acts of spending, “the modus vivendi under the boot of the modus operandi,” as Lewis Lapham describes it. Yelp won’t help you find a stoop.

For about two months (the same duration as the Paris Commune), a parallel universe arose in Zucotti Park, a moneyless space where people gathered to exchange ideas and be warmed in each other’s company. We assembled there for the sake of the very idea of assembly.

Harvey fears that in New York and elsewhere, the city has lost that fundamental element that energized urban life since classical times: the agora, the open air commons. New York, he has said, has plenty of space for the “the assemblage of tulips and so on, but we don’t have a place where people can assemble.” The way a city encourages us to live shapes both how we relate to each other and our politics. In the city, “the neoliberal ethic of intense possessive individualism, and its cognate of political withdrawal from collective forms of action, becomes the template for human socialization.” For city dwellers to change their cities (and in so doing, change themselves), they must first turn to their neutered squares and parks and reclaim them as political spaces.

Harvey celebrates the occupation of Zuccotti Park as just the kind of real and symbolic act necessary to turn the tide. Occupy Wall Street sought to “convert public space into a political commons, a place for open discussion and debate.” An Athenian agora emerged in the glass canyons of lower Manhattan.

I spent quite a bit of time at Zuccotti Park, but not enough to cast myself as some committed tribune of the occupation. I was but another happy barnacle, clinging to the hull of the OWS movement. While those around me debated the ins and outs of the occupation, its prospects for growth, the challenges ahead and within, and so on, I was content to simply soak it all up. Mine was a cheery, casual sort of connection to the park. As someone who grew up in New York City, I felt a refreshing sense of relief more than anything else. The park offered a rare escape from the eternal clamour of acquisition. I recalled what Henry James wrote upon returning to New York in 1904, after decades away. He perceived the asphyxiating modernity of the city as “the endless electric coil, the monstrous chain that winds round the general neck and body.” Occasionally, however, he would find quieter, older streets in Greenwich Village that reminded him of his childhood there and promised a reprieve, however brief, from “the awful hug of the serpent.”

For about two months (the same duration as the Paris Commune), a parallel universe arose in Zucotti Park, a moneyless space where people gathered to exchange ideas and be warmed in each other’s company. We assembled there for the sake of the very idea of assembly. However inchoate, the park put forward an alternative vision of urban life, of what it meant to be part of a community of strangers.

“Liberty Square” would have survived if not for the late-night crackdown that expelled the permanent occupation in November 2011. Without this symbolic and logistical locus, much of the energy drained from the OWS movement. No number of marches or rallies can compensate for the bold claim of urban space made truly public, an act that succinctly summarized the inequity in American society while dramatizing a means for its redress. The occupation was the argument.

All sorts filtered through the park: scruffy young anarchists, workers on extended lunch breaks, schoolteachers from the outer boroughs, students from universities near and far, and the much larger undefinable mass of everyday people. In a neighborhood now uniformly the quarter of bankers and financiers, OWS was a reminder of that world of difference purged from the city. McCabe would have been appalled. It was almost a throwback to the late nineteenth century, when the Five Points lurked just blocks away, so perilous, so loud, and so other.

Kanishk Tharoor is a “Writer in Public Schools” fellow at New York University. His articles on politics and culture have appeared in publications in various countries. His short fiction has won a few prizes and been nominated for a National Magazine Award. He lives in New York and, sometimes, he tweets.