As protests erupt and federal troops are deployed in response to ICE raids, the city’s layered identity is once again thrust into a landscape of tension and resistance. In her 2019 essay, Carolina Miranda remaps LA not as a city of fixed enclaves, but of hybrid belonging— where Mexican plazas meet Chinatown gas stations, where Chicano teens sip Taiwanese bubble tea on Cesar Chavez Ave. In the popular imagination, LA is often cast as a Westside yoga girl who’s into colonics and kale. But as Miranda illustrates, LA is more likely to be a “little Mexican girl, grooving to a cover of ‘Juana La Cubana’ in the plaza—a space her ancestors helped devise.”

—Guernica, June 2025

—

Read more of our new series on American mythology, Rewriting the West.

Afavorite pastime on Los Angeles social media is to describe “the most LA thing ever.” Crystals, avocado toast, and gluten-free soy sauce invariably turn up. But in my mental map, the most LA thing ever is the Shell station at the intersection of N. Hill Street and W. College Street, in Chinatown. The gas is wildly overpriced, and the attached convenience store is decorated solely with images of shoplifters. But of interest to me are the canopies that shelter the gas pumps, in the form of upturned, flying eaves typical of sweeping Chinese rooflines (a style that dates back to the Han Dynasty) and shingled with Spanish tile.

In the world of architecture, such a combination might be regarded as perplexing, even a travesty. Not in LA. In this one curious gas station we see reflected Los Angeles and California writ large. It’s the most LA thing ever, in a place where Mexico meets China; where a historic Mexican plaza—the place where 44 Mexican pobladores laid down the bones of the early city’s Plaza de Los Angeles—abuts Chinatown; where Chinese bakeries selling red bean buns and almond cookies feature signs that read, “Se vende café.”

To others, the most LA thing ever might be a sunny landscape redolent of orange blossoms, the entertainment capital, the terminus of the American West. In that Los Angeles, California is considered in relation to the East, set against a backdrop of the rest of the United States. This is California as a product of westward expansion, of railroads, of Dust Bowl migrants, of Hollywood filmmakers who landed amid orange groves to make movies and avoid New Jersey patent laws. It is Anglo California, shaped by Europe and its descendants. It is California as a bubbly blonde.

These images dominate the popular imagination, to some degree, because of the way that US history is often told. The story travels from East to West—beginning at the moment of European arrival in Virginia, followed by the inevitable westward-ho journey. In this story, and on this map, California is West—the last stop for Manifest Destiny before skidding into the Pacific Ocean. This, too, is Los Angeles, but it’s not the entire story.

Before California was West, it was North and it was East: the uppermost periphery of the Mexican Empire, and the arrival point for Chinese immigrants making the perilous journey from Guangdong. It was part of different maps that co-exist, one on top of the other: layers of visions and lesser-known narratives, that are ongoing and still unfolding.

***

This other, deeper story of Los Angeles is contained in an unremarkable map that hangs on the first floor of the Chinese American Museum, a small historical institution downtown. The map is neither a historical relic nor particularly aesthetically pleasing, containing no fine engravings of fantastical sea creatures. It doesn’t even have a formal name.

Instead, the map is a utilitarian, black-and-white reproduction of an early 1900s plan that charts the blocks around LA’s historic core. Anchoring the upper left hand corner is the Plaza de Los Angeles, which, in those days, was employed as a space for commerce, celebrations, and rallies in support of labor movements and Mexican revolutionaries., Extending from the plaza is a rambling geometry of urban blocks. Laid over it is a clear plastic sheet that shows an outline of the neighborhood’s grid as it stands today.

The map tells the story of a city evolving over the course of more than a century, from sleepy agricultural outpost to railway destination to car capital. Where once there were narrow lanes, now there is freeway. The eastern swath of the map, formerly a warren of small streets, now bears the blocks-long footprint of Union Station, the graceful Mission Revival rail depot, completed in 1939.

The map tells other stories, too.

The Spanish street names—Alameda, Sánchez, Los Ángeles—tell the story of Spain establishing a colonial outpost on the fringes of its Mexican Viceroyalty: El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Ángeles, founded in 1781 on the banks of the Río de Porciúncula (now the Los Angeles River). The plaza and its nearby streets take their form from the urbanism of colonial Latin America—a central plaza surrounded by a city’s most important civic buildings—a design brought north by pobladores from Sinaloa, Jalisco and Durango.

The map also tells the story of Los Angeles as a haven for the Chinese—of immigrants from Guangdong on the South China Sea, who fled a region racked by war in the mid-nineteenth century for the land they dubbed Gum Saan, or Gold Mountain, inspired by the tales of the California Gold Rush. It is this piece of Los Angeles that served as the city’s original Chinatown.

As long as Los Angeles has been part of the United States, Chinese have belonged to LA. In 1850, the year that California joined the union and the area had its first US census, the city’s population was a booming 1,600 souls; its most prominent businesses were gambling houses and saloons. At least two Chinese Angelenos appeared on that first census: Ah Luce and Ah Fou, house servants working for a ship’s captain.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the downtown area had transformed into LA’s first Chinatown. On the map, this presence is manifested in the names of the businesses that once lined the streets around the plaza: Hing Chong Co., Sun Wing Wo, and Kong Nam Far Eastern. Union Station sits atop the old Chinese Quarters—a.k.a. the old Chinatown. “New” Chinatown now lies a few blocks away.

The map at the Chinese American Museum marks a Los Angeles of yesteryear. It also marks the Los Angeles of the present: two migrations, the Latin American and the Asian. These were supplemented in subsequent decades by new waves of people: Japanese and Salvadoran, Korean and Guatemalan, Vietnamese and Peruvian. Since 2000, California has been a “majority-minority” state. According to an analysis published in 2016, the average Californian is a 35-year-old Latina who lives in LA’s Koreatown.

When Anthony Bourdain toured Los Angeles for his television series “Parts Unknown,” he chose to cruise Koreatown with Roy Choi, the founder of the renowned Kogi Truck, a purveyor of that uniquely hybrid cuisine: the Korean taco.

“What is LA?” Bourdain asks. To help answer that question, Choi takes him to the city’s Eastside to hang with Chicano photographer Estevan Oriol and see low-riders.

Los Angeles as the North. Los Angeles as the East. The Los Angeles that has been here all along.

***

Ptolemy, the Greco-Egyptian geographer from classic antiquity, defined cartography as “a graphic representation of the whole known part of the world, along with the things occurring in it.” The description is straightforward, even obvious: maps are representations of what exists on the Earth.

But cartography is neither that clinical nor that impartial. No map can represent everything. “To avoid hiding critical information in a fog of detail, the map must offer a selective, incomplete view of reality,” wrote Mark Monmonier in his 1991 book How to Lie With Maps. “There’s no escape from the cartographic paradox: to present a useful and truthful picture, an accurate map must tell white lies.”

Maps, therefore, embody a point of view: the social, cultural, political and geographic biases of the mapper, and the powers that the mapper serves. And in the process, maps shape our view of the world. They assign value to locations, mark places worth knowing, and emphasize the primacy of some regions over others. In order to account for the curvature of the earth, Gerardus Mercator distorted the areas closest to the poles when crafting his famous projection in 1569. To see a Mercator map, therefore, is to see a world in which Europe and North America look bigger than they really are. It is a map created out of a colonial mentality that went on to feed and legitimize that mindset—and still does.

Some maps reveal long-ignored narratives. Indigenous maps from Mesoamerica, for example, devised at the time of the 16th century Spanish conquest, rendered the world in abstraction (they weren’t attempting to depict exact dimensions or scale), but instead linked the land to a lineage of rulers. Other maps are about establishing a dominion: the 1507 plan created by the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, which employed the name “America” for the first time, featured an American continent that lay largely empty, implying that this was land for the taking. Never mind that millions of indigenous people—entire empires—covered the continent at the time.

Just as cartographic emptiness invited settlement, it also created a space into which others could project their illusions. Well into the late seventeenth century, cartographers depicted California as an island that was separated from the American mainland by a body of water they dubbed the Vermillion Sea. Early Spanish explorers had mistaken the Baja Peninsula for an island, and California took its identity from this mistake.

The name California refers to an island mentioned in the 16th century chivalric novel Las Sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. The book describes an “island named California,” located to the right hand of the Indies, “very close to Earthly Paradise, a place populated by black women, without a man to live among them.” For centuries, California has had projected upon it the fantasies of men who hail from elsewhere.

By the 1700s, California had made it onto the cartographic mainland—as part of Alta California, the vast northern Mexican territory that included what is today Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado and New Mexico. To see California on a map as part of Mexico is to see a California as North. It is a California that is linked to Mexico via topography—the arid valleys and craggy mountains of the Basin and Range Province, which extends from the Golden State into Nevada and the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua. It is also to see a California that is connected to Mexico City via political boundary. Los Angeles lies roughly 800 miles closer to the Mexican capital than it does to Washington, D.C.

These maps, too, feature the tropes of empty space. A plan from 1826, printed by the influential Henry Schenck Tanner—a cartographer whose work helped paint a picture of the lands that would soon become the American West—features a beguiling amount of terra incognita and, in the vicinity of the Mojave Desert, a short text that reads: “These mountains are supposed to extend much farther to the North than here shown but there are no data by which to trace them with accuracy.”

***

Sometimes the omissions are intentional. In 1786, five years after the foundation of Los Angeles, José Argüello, a Spanish Army captain, sketched out the earliest known map of the city. It is more geometric abstraction than scale map. On his sheet, he marked only two natural features: an irrigation ditch and the river. Around these, he laid out a series of squares. To the west of the river, a handful of squares represent the pueblo; to the east, other squares serve as inventories of the settlers’ agricultural fields.

Left entirely unmapped: the area’s indigenous communities.

Some 5,000 indigenous people, primarily of the Tongva ethnicity, were living in the Los Angeles basin—some scholars estimate—when Argüello arrived in Southern California to seize territory in the name of the King. The Tongva’s most prominent village was Yaanga, and it was situated to the south of the colonial pueblo. (Its exact coordinates are a subject of debate.) What can be confirmed is that Yaanga’s most prominent feature was a 200-foot sycamore tree known in Spanish as El Aliso, which functioned as a sacred meeting site for local indigenous leaders.

As in other colonial settlements, the Spanish built their colony on the backs of the indigenous people. The Tongva served as field hands and construction workers. They endured beatings, disease, and rape. By the early nineteenth century, in the words of one historian, their village had begun to look like a “refugee camp.” By 1845, its last vestiges were moved across the river to present-day Boyle Heights. After the Americans took over, in 1850, whatever remained of Yaanga and its residents was inhaled by the growing city.

Yaanga doesn’t appear on European maps, and its existence went unmarked by known Mexican or US cartographers. But the Spanish sure knew about it: they built their own pueblo right alongside it. El Aliso, however, does feature in late nineteenth-century photographs, where it can be seen towering over squat adobe homes and, later, a winery. By 1895, however, the tree was gone—chopped up for firewood and sold off. Its precise location was never mapped, but various estimates put it within view of the Déjà Vu Showgirls strip club on Commercial Street, underneath an on-ramp to the southbound 101.

Yaanga’s erasure—from maps, landscape, and memory—has been virtually complete.

***

In the wake of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), California was transformed from a northern Mexican outpost into the US West. It was not done by the simple redrawing of maps, but by the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

When the rail lines reached Los Angeles, they delivered droves of prospectors from all over the United States. Railway brochures from the era played to the fantasy of the West as land of milk and honey, advertising stunning vistas, noble Indians, and “popular summer resorts.” Early twentieth-century Los Angeles city booster Charles Lummis did his part to welcome the flood of English-speakers by concocting a rhyme to help the new arrivals correctly pronounce the name of the city: “The Lady would remind you please / Her name is not Lost Angie Lees.”

California’s reorientation from Northern settlement was soon reflected in the redrawing of maps. An 1850 plan, produced by JH Colton and Co., shows a United States that includes the Mexican territories that were annexed after the war. A pink line marks the new international border, separating Alta from Baja. California is now listed—in English—as “Upper or New California.”

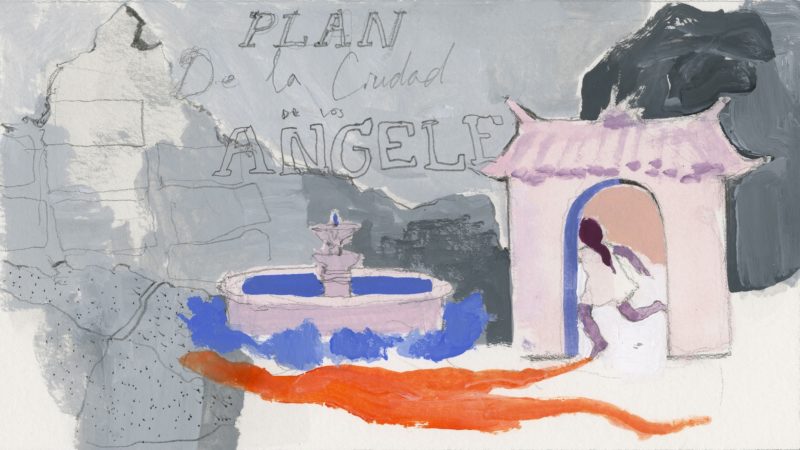

With the arrival of the Easterners came the first detailed map of Los Angeles, produced by surveyor Edward Otho Cresap Ord, a US Army lieutenant who had served in the Mexican-American War. Ord was aided by William Rich Hutton, who crafted the elegant map drawings. The purpose was to create an accounting of the city for the state’s new federal government in Washington, D.C. The “Plan de la ciudad de Los Angeles” was completed in 1849, at a time when LA consisted of a single adobe church, a cemetery, and a few dozen homes, also constructed from adobe. (One of these, the Avila Adobe, built in 1818, still survives on Olvera Street, just off the plaza—its graceful, shaded courtyard a respite from the roar of buses on nearby Alameda Street.)

Ord’s map, naturally, contained plenty of empty space—incorporating dozens of empty lots that presumably awaited the arrival of settlers from the East. And he recorded the street names in both Spanish and English: Calle de la Eternidad is also listed as Eternity Street (later, Broadway). Calle Principal became Main. The city would soon speak English. Los Angeles was becoming the West.

While the Ord map may have been intended to claim Los Angeles for the US, it nonetheless reveals the city’s inherent Mexican anatomy. The city was laid out at a 45-degree angle from the cardinal points, in accordance with the Laws of the Indies, the royal Spanish edicts that governed the design and administration of all colonial settlements. The configuration purportedly allowed for the best access to light and protection from wind, which was thought to blow from the four cardinal points. In his 1996 memoir Holy Land, essayist D.J. Waldie describes it as a plan that “came from God.”

As scores of Anglo settlers landed in Los Angeles in the 1880s, they began to mold the city grid to their own views of urbanism. These were inspired by Jeffersonian ideals from the East Coast that suggest cities take their form from the cardinal points, and therefore be laid out on a north-south axis.

Open any contemporary map of LA and you can see the exact spot where the Mexican gives way to the American: Hoover Street, just west of downtown, in which angled Mexican streets bend to accommodate the US grid. In a 2010 essay, Waldie described that point as “crossing from one imperial imagination to another.” A shift in power, in place and identity—all marked by a single line.

***

In his map, Ord diligently marked street names, topography, and the families to whom designated agricultural lands belonged. (Many of these names now remain in Los Angeles memory as city streets: Sepulveda, Vignes, and Sanchez.) Ord, however, omitted one crucial feature: the plaza.

The city block that it occupies made it into the map. But the plaza itself went unlabeled. Perhaps it was an oversight, an urban feature that may have seemed inconsequential to a surveyor from the East Coast. The omission, however, marginalized a crucial feature of Los Angeles.

Under Mexican rule, the bare plaza—a photo from 1862 shows a rough square crisscrossed by footpaths—had been of critical importance. It anchored social and civic life in the city: a site of weddings and inaugurations, and, ultimately, the place where United States military commanders parked their troops when they invaded during the Mexican-American War—complete with brass band playing “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

Even more, the plaza represents an important facet of the mestizo, an urban space that mixes elements of the indigenous and the European. In the early days of colonization, plazas in Spain were small, medieval affairs, tucked into a city’s available spaces. But plazas among Mesoamerican cultures were power centers—larger, more open, more ceremonial, more central, often surrounded by a settlement’s most important buildings. In his engaging 2008 book The Los Angeles Plaza, William David Estrada notes that the vibrant plazas that developed in Latin America, “especially in Mexico, were as much a product of the Indian world—the world of the Maya, Toltec, and Aztec before the conquest—as they were European.”

The Plaza de Los Angeles, therefore, is not simply a random green space. It is the urban embodiment of a non-Anglo, hybrid American space—American, in the sense of belonging to the continent, not simply the US. Of the 44 pobladores who arrived from Sinaloa, Durango, and Jalisco, and who founded the City of Los Angeles in 1781, only two were Spaniards. Most of the people were indigenous, mixed-race, black, or mestizo. The plaza was their shared space—a space that reflected the city’s location, not as a Western outpost, but as a Northern one.

Today, the Plaza de Los Angeles is lined with stately trees and punctuated by a bright bandstand. It is a prominent tourist attraction, part of the El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument that includes nearby Olvera Street, a passageway stuffed with vendors dispensing ceramics, ponchos, and hot churros dipped in sugar and cinnamon. The plaza is no longer the center of civic life in Los Angeles, but it remains an important social space. On weekends, musicians entertain Latino families who attend religious services in the area, then descend on the square to eat and dance.

In the popular imagination, LA is often cast as a Westside yoga girl who’s into colonics and kale. But Los Angeles is more likely to be a little Mexican girl, grooving to a cover of “Juana La Cubana” in the plaza—a space her ancestors helped devise.

***

As important as the plaza has been to Mexican life, it has been critical for other groups, too—in ways both poignant and chilling. That takes me back to the simple map that hangs at the Chinese American Museum.

Shown on the map is a short lane that once ran parallel to Los Angeles Street, just off the plaza. Sometime during the era of Mexican independence, it became known as Calle de Los Negros. As the story goes, one of the alcaldes (mayors) of the era baptized the street after the mixed-race families who lived there, and the name stuck. After California was ceded to the US, Calle de Los Negros was Anglicized to “Negro Alley”—never mind that most the people who lived there by the end of the nineteenth century were Chinese.

Calle de Los Negros, in fact, was the site of a notorious riot known as the Chinese Massacre of 1871. The ruckus started when a white man was accidentally killed in crossfire between two Chinese groups. In the wake of his death, a mob of 500 people “of all nationalities”—including police officers, a city council member, and a reporter—began a brutal assault on any and all Chinese people living in Negro Alley. Some were lynched; others were shot. Bodies were mutilated and dragged. An estimated 17 people died; seven men were ultimately convicted for manslaughter.

It was an episode of vicious anti-Asian sentiment that drew international headlines. It also drew attention to a street whose name was born of racism—racism that carried into Los Angeles map-making. Calle de los Negros was frequently referred to in English as “Nigger Alley.” And in some early twentieth century maps, it is that appalling pejorative that appears as official map nomenclature, including on the historic sheet at the Chinese American Museum.

Today, all that remains of Calle de los Negros are the maps. The lane was later renamed Los Angeles Street. In the 1950s, it was razed and replaced with a freeway on-ramp and a parking lot. Sometimes ugly histories are also erased from the faces of cities and their maps.

In the 1930s, much of old Chinatown was bulldozed to make way for Union Station. The community was relocated a few blocks to the north, to a complex of fanciful buildings that bear the flourishes of Chinese temple architecture. The new Chinatown is less residential and more commercial, cluttered with restaurants and tourist markets and a photogenic statue of Bruce Lee (not to mention a singular Asian-Mexican gas station). Subsequent generations of Chinese immigrants have chosen not to live in this area. Instead, they have moved to communities such as Alhambra and Monterey Park, further east.

But one vestige of the old Chinatown still survives: the Garnier Building, a red brick, Romanesque Revival structure completed in 1890. The Garnier, which appears in the map at the museum, once served as an important hub for Chinese life in Los Angeles. It was here that residents could visit the herb shop, get access to financial services, and support organizations that fought for citizenship rights. (The Chinese Exclusion Act prevented Chinese Americans from applying for citizenship until 1943.)

The Garnier is now the home to the Chinese American Museum, which helps preserve the community’s history. A small courtyard marks the entrance to the museum, where paper lanterns bob in the breeze. It is a touch of Asia in a structure that lies between tilted streets with Spanish names, just steps from the Plaza de Los Angeles.

To look at Los Angeles as West is to see a charming, yet incomplete, picture of Los Angeles. It is one narrative that overwrites many. The Los Angeles of the West is a Los Angeles molded to Anglo preconception. It is a Los Angeles of railroads and Hollywood. It is the end of the line.

The Los Angeles of the North and the East has been here for centuries, and it is everywhere. It has given Los Angeles its name and its grid. It has shaped the city’s architecture and supplied its most distinctive flavors. It is Chicano teens drinking Taiwanese bubble tea on an avenue called Cesar Chavez. It is Latino families flocking to a 1960s American diner that’s been converted into a pan-Asian noodle joint. It is Asian low-riders and Salvadoran sushi chefs. It is the point of entry—the beginning.

This piece, part of our Rewriting the West series, is made possible by a generous grant from the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University.