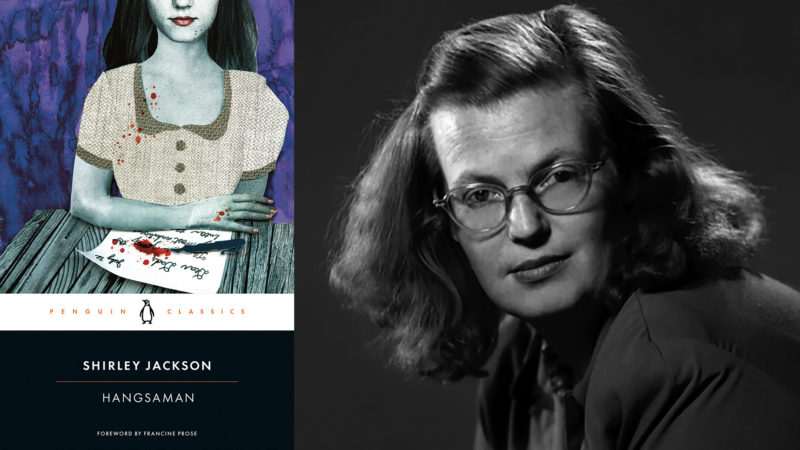

Hangsaman, Shirley Jackson’s murky and disquieting 1951 novel, is a frantic read. It careens down unlit dormitory corridors and bounds around the psyche of its seventeen-year-old protagonist, Natalie Waite, as she arrives at college and plummets into psychological collapse. “Suppose, actually, she were not Natalie Waite, college girl, daughter to Arnold Waite, a creature of deep lovely destiny,” Natalie wonders, her mental splintering already underway, “suppose she were someone else?” Soon, she develops an intimate friendship with a girl in her dorm named Tony — who, it turns out, Natalie has invented.

Jackson’s novel is hazy, filtered as it is through Natalie, and uneven in places. Tony slips in slowly, like toxic gas, only to disappear abruptly, leaving questions about Natalie’s mental state unanswered. But about the gendered nature of Natalie’s unraveling, Hangsaman is unambiguous: Natalie is at least partially undone by a sexual assault that occurs early in the novel, at her childhood home; more broadly, she is the product of an upper-middle-class 1950s America that does not care about resolving or supporting her personhood. The other women in her world include a faculty wife who, feeling her selfhood subsumed by her marriage, lives in alcoholic misery, and Natalie’s own mother, who throws elaborate garden parties in the suburbs and divulges, “it isn’t any single thing…it’s just that…this is the only life I’ve got…this is all.”

Hangsaman is, in this respect, an early effort at what would become a career endeavor for Jackson: to explore the fragmentary internal landscape of her generation of women, often through themes of madness, fracturing, and disorientation. Jackson herself was a mother of four, and married to literary critic Stanley Hyman; while her love for her children and her Bennington home life permeates her writing (including in the autobiographical Life Among the Savages), she struggled to balance the demands of mid-century womanhood with her desire to produce serious literary works. Natalie is one manifestation of this tension.

“Her body of work constitutes nothing less than the secret history of American women of her era,” writes biographer Ruth Franklin in Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. “The stories she tells form a powerful counternarrative to the ‘feminine mystique,’ revealing the unhappiness and instability beneath the housewife’s sleek veneer of competence.” (In fact, Natalie Waite’s unraveling predated Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique by a dozen years.) Seventy years after its initial publication, Hangsaman’s prescience makes it worth revisiting. It also provides a sketchy roadmap of where Jackson would head later — the unsettling, female-centered psychological novels that were her late masterpieces.

For decades, Jackson’s name had stayed almost entirely synonymous with “The Lottery,” her bleak short story about a ritual human sacrifice in a small suburb (in true Jackson fashion, the woman sacrificed in that story, a housewife and mother, cries, “It isn’t fair, it isn’t right,” as her community destroys her). That story, originally published in The New Yorker, garnered Jackson the most public attention she received in her lifetime, but a more recent cultural evaluation of Jackson — including reported books like Franklin’s and cinematic reimaginings like Josephine Decker’s Shirley — encourages us to remember Jackson for a diverse career, spanning humor and pathos as well as horror.

I spoke to Franklin about Hangsaman and some of Jackson’s subsequent novels — The Bird’s Nest, The Haunting of Hill House, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle — which, in many ways, pick up where Natalie Waite left off.

—Amanda Feinman for Guernica

Guernica: Hangsaman is notable for its psychological precarity — a slippage between reality and unreality that Natalie, as well as the reader, experience. How did Jackson understand that slippage, and the relationship between realism and surrealism?

Franklin: Jackson never wrote a realist novel. She’s always playing with the boundaries of the human mind — where our perception ends and reality begins. And she’s always been interested in introducing the maximum amount of ambiguity into her writing. In Hangsaman, you could argue that she goes a bit too far; certainly critics at the time were completely puzzled by this novel. Most of them misread it and thought that Tony was a real person, and you almost can’t blame them for it. In her next book, The Bird’s Nest, she would make it more clear: while that book is narrated by a character literally inhabited by multiple personalities, there’s a steady foil in the psychologist who treats her. In Hangsaman, there’s no foil like that. We get it all through the eyes of Natalie, who is, to put it mildly, an unreliable narrator.

Guernica: The psychological ambiguity and precarity you’re talking about is also closely related to gender. What might Jackson have wanted the psychological dysfunction of her women characters to symbolize?

Franklin: There’s a sociological way you can interpret it. This was a moment when women really weren’t sure what they were supposed to be; there was no way to satisfy all the demands placed upon them. You had to be a mother and a housewife but at the same time maintain your youth and your beauty, and play all roles for all people. It’s no surprise that this is when we start seeing a huge rise in diagnoses of multiple personality disorder, predominantly among women. In Jackson’s work, I think it’s a metaphor for the pressure of having to play all these roles, from which there is no real escape.

Guernica: In Jackson’s work throughout her life, we see a continuing interest in female madness functioning as metaphor — in The Bird’s Nest, with multiple personality disorder, but through other kinds of psychological disintegration in female characters, too.

Franklin: She’s really only interested in female psychology. Her male characters are foils or ciphers. It’s the women with whom the real action lies, for better or for worse.

Guernica: As you show in your biography of Jackson, she, too, seemed to struggle with negotiating multiple facets of herself — writer, mother, wife, public figure. How much of Jackson might we see in these fragmented women that she writes?

Franklin: I think they all have an element of her — just as the happy housewife in her motherhood memoirs also contains an element of her. That’s another thing critics of her time were puzzled by: the idea that the same person could have written these weird thrillers of psychological suspense and fracturing, like Hangsaman, which basically nobody understood, and also Life Among the Savages, a huge bestseller and her most accessible book. She really resisted the idea of having to be one particular thing or another.

Guernica: I want to talk about some of Jackson’s later novels as they relate to Hangsaman. The Haunting of Hill House is a gothic ghost story; its protagonist, Eleanor, is susceptible to this house’s dark influence because she is lost, alone, and on the psychic brink. In We Have Always Lived in the Castle, sisters Constance and Merricat survive a mysterious mass death of all their relatives and completely isolate themselves in the aftermath, building a new life governed by illogic and totally disconnected from reality. We can clearly draw a line from Natalie to these characters, but those other books are arguably more accessible and were better received. I wonder whether Hangsaman might be seen as an early draft of those novels — thematically similar, but perhaps not yet the form Jackson would later master?

Franklin: Certainly each of those novels revolves around an unstable female protagonist. But in Hill House and in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, it’s the unstable female protagonist who really gives the novel its agency — who drives the action and the consequences for all the other characters. In Hangsaman, Natalie doesn’t have the same kind of agency. The reader also doesn’t have the same kind of access to her thoughts and ideas. You perceive her through a distorted mirror, which is partially the way Natalie experiences her own life: that’s the effect that Jackson is trying to create. But I think there is an unintended consequence there, of fuzziness for the reader around not only the action, but the character herself. Jackson would develop control over her use of ambiguity more successfully in those later novels.

Guernica: I agree about the lack of access to Natalie. But her similarities to those later protagonists make these novels feel like they’re all working toward the same goal.

Franklin: And the same essential question: How much agency can this female character have? To what extent is she acted upon, versus fulfilling her own destiny? That’s the central dilemma for Eleanor at the ending of Hill House.

Guernica: Right. Eleanor kills herself, but it is not made explicit whether she is under the influence of this house or whether she is in control. On the subject of Hill House, I’m curious about Jackson’s thematic interest in houses and homes, particularly houses and homes gone wrong. They are everywhere in Jackson’s work, including in Hangsaman: Natalie’s childhood home, where the action starts, isn’t stable, gets corrupted. What did that theme allow for Jackson, as she kept returning to it?

Franklin: In a lot of ways, the Waites in Hangsaman represent Jackson’s own nuclear family. They weren’t close. There were a lot of unfulfilled expectations. Shirley’s mother was the big driver of the idea that Shirley should conform to social expectations — that she be a debutante, that she wear a certain kind of clothing and go out with a certain kind of boy. And Shirley made it pretty clear from the beginning that she wasn’t going to meet these expectations. In literature, the house can represent all kinds of things: It can be the human body, it can be the mother. But more than anything, for Jackson, it represents marriage, and the institution of the family, and the way that what goes on inside the house either conforms to and supports that institution, or doesn’t.

Guernica: One reading of Hangsaman might be that Natalie’s disintegration happens after she butts up against the expectations Jackson resisted. Elizabeth Langdon, the faculty wife, is a figure in Natalie’s life who exemplifies what might happen if she conforms.

Franklin: Not just what might happen, but the most likely end point for a woman like her.

Guernica: Yes. So, with that in mind, what do you make of the resolution of Hangsaman? It’s — for me, anyway — confusingly uplifting.

Franklin: I have to say, I don’t really believe the ending. I don’t find it credible. It’s really abrupt. She and Tony are in this nightmarish wonderland, an amusement park-type place. And then Tony apparently makes a pass at her, and the scales fall from her eyes, and she awakens to reality. She’s able to go back to college. Part of what’s in there is Shirley’s attitude toward lesbianism, mixed in with the attitudes of her time. The idea of being attracted to women was a source of a deep horror for her, for reasons that I don’t really find appropriate to speculate on; it’s just important to know that that existed as a source of a lot of confusion and fear for her. I guess I see it as a wish-fulfillment ending: that it would be possible to just wake up from the nightmare, and everything’s okay. In Shirley’s life, it didn’t work that way. And for most of us, that doesn’t feel psychologically true.

Guernica: It’s also not the case for other Jackson protagonists. For characters like Eleanor, there are consequences, or a kind of closure.

Franklin: Things play out in the way that they need to play out. Whereas in Hangsaman, things don’t get worked out. They get wished away.

Guernica: Sexual fear is a big part of the ending, as you mentioned, and that occurs early in the novel, too: The action begins with a garden party at Natalie’s childhood home, and it is heavily implied that she is sexually assaulted by one of her parents’ friends. What do you make of that recurrence?

Franklin: Well, all this is speculative, obviously, but it does seem like sex brought up conflicting emotions for Jackson from the beginning of her relationship with Stanley Hyman. There may have been an event early in their relationship that she regarded as a kind of rape. But regardless of whether that’s based in fact, it’s clear that sex was a source of tension and conflict for her, again probably even more so than for your typically repressed, pre-sexual revolution American woman. I don’t know exactly why she chose that plot event, but I think it works as an inciting incident because it generates all this psychological confusion for Natalie.

Guernica: Right, it casts a shadow over the whole book. To switch gears a bit, I want to talk about the genres Jackson dabbled in. Hangsaman is a psychological thriller, which is also very satirical…

Franklin: It’s a campus novel….

Guernica: It’s a lot of things, and many of her books are a lot of things, even though she’s often thought of strictly as a horror writer. So I’m curious about Jackson’s interests in both horror and humor, light and dark.

Franklin: I don’t think she was capable of writing in a genre. The closest she ever gets to a real genre novel is with Hill House, which is a ghost story, but it’s also a really profound psychological novel. My sense is that she wasn’t interested in describing her writing in terms of genre; that wasn’t a useful term creatively, as far as she was concerned. She was mostly interested in writing the kinds of stories that compelled her.

Guernica: That makes a lot of sense, given her tendency to push against other kinds of enforced boundaries. Something that strikes me about both horror and satire is that they’re ways of looking at social anxieties in narrative extremes. They’re just different extremes.

Franklin: And the balance between them is really important. That’s something Jackson does effectively in Hangsaman, as well as in The Haunting of Hill House. Where there’s a lot of darkness, it’s lightened periodically by moments of real humor.

Guernica: I want to return to Jackson’s public reception. For a long time, she wasn’t widely or fully recognized. Her name was associated almost entirely with “The Lottery.” What do you think kept her from the spotlight for so long? And what is driving the renaissance of critical conversations about her right now?

Franklin: Well, some of what kept her from the spotlight was circumstantial. She died young, in a somewhat early stage of her career. And the person who would have been her champion, Stanley Hyman, also died young, and wasn’t able to fulfill that role for her. I think she was always there in the background as…I hesitate to say a “cult writer,” but one of those writers who hadn’t quite gotten her critical due, and was ripe for reassessment.

When the Library of America brought out that complete collection of her work in 2010, that’s what really got the Jackson reevaluation going. That was the book that happened to land on my desk, and it got me started thinking about Jackson in a different way. Anybody who opened that book thinking that the extent of her work was “The Lottery” or The Haunting of Hill House was going to be in for a very huge surprise. By publishing a much larger sample of her work, readers were given a sense of how multifaceted she was as both a person and a writer. For her truly to be taken seriously as a literary writer, I think one has to look outside the genre box and try to understand her work as a whole.

Guernica: Gender is part of this critical reevaluation, too. A lot of female writers are now coming to the Jackson conversation.

Franklin: It’s been mostly female critics who are leading the drive to reevaluate Jackson. And it’s no accident that Jackson’s work is so female-focused: that had a lot to do with her marginalization. Male critics of her time simply weren’t ready to see a story with female protagonists as a universal narrative.

Guernica: What did you think of Josephine Decker’s Shirley?

Franklin: First of all, there’s a myth, which got reinforced in the biopic, that Hangsaman has to do with Paula Welden [the college student who disappeared in Bennington, Vermont in 1946]. There just is no evidence for this, and it maddens me that it keeps getting repeated. I actually shouldn’t call that movie a biopic. Not only does it offend the memory of Shirley Jackson by erasing her as a mother, it chooses Hangsaman to be the novel that she’s supposedly working on in Bennington. She didn’t even write it in Bennington! She wrote it when she and Hyman were briefly living in Westport, Connecticut.

Guernica: That movie also puts Jackson in the role of the faculty wife — which, within the context of Hangsaman, is the Elizabeth Langdon character, not the Natalie character. That feels strange to me.

Franklin: But that’s the thing about Hangsaman! I think maybe that’s the key to its fractured and kaleidoscopic feeling. Shirley actually is all of those characters. She is Mrs. Waite and she is Elizabeth and she is Natalie. She plays all of those roles. No wonder it feels so broken apart.