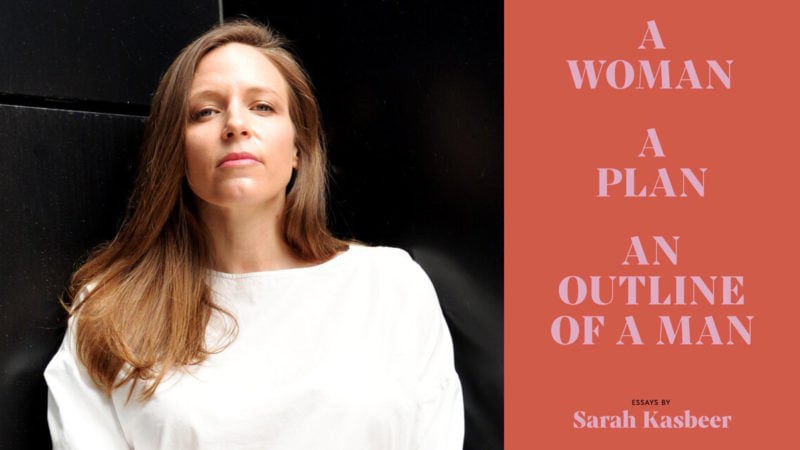

With A Woman, A Plan, an Outline of a Man, Sarah Kasbeer brings us a memoir in essays that pushes against the coming-of-age stories so many of us grew up with. Hers is not a straightforward story of becoming, but an unflinching unraveling of the forces that shape the ways a girl finds herself in the world.

Kasbeer’s experiences with the male gaze, male violence, and men’s love reveal how tightly connected many young women’s stories of selfhood are to something wholly outside themselves—or connected, rather, to people who consider that selfhood to be entirely beside the point. Growing up as a girl in patriarchy is not a new experience, but as proven by a new crop of books—A Girl is a Body of Water by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, Being Lolita by Alisson Wood, You Exist Too Much by Zaina Arafat, and Tomboyland by Melissa Faliveno, among others—the subject is at once startlingly universal and intensely individual.

Though they capture very different experiences, these books share an understanding that grappling with trauma is necessary to understanding the self. Kasbeer’s sharp, lyrical interrogation of her American girlhood illuminates both the quiet, everyday harm women experience, and the more volcanic damage that shapes not only how we see the world, but how we see and know ourselves. Her essays are not only about the formation of a self, but about the critical, often painful reconstruction of a self that follows.

I found myself not only furiously underlining passages, but feeling frequently shaken as I reconsidered chapters from my own past I had understood to be typical, benign, run-of-the-mill—and now recognized as anything but. Like when I lapped up praise for being “chill” while chastising myself for not feeling more relaxed. Or when my middle school principal reprimanded me for being “disrespectful” because I wrote a school newspaper article about the questionable motivation techniques practiced by male field hockey coaches. Or when I drank myself into blackouts for most of my early sexual experiences.

Kasbeer is particularly adept at pointing out the ways girls are both implicitly and explicitly trained to seek confirmation of their own experiences and feelings from external sources. In one chilling example, she shares an email from her rapist in which he tells her he is “sorry you think its ok to accuse someone of something like this TEN YEARS LATER!” So many “apologies” to women are actually condemnations for failing to feel or think correctly—for failing to be whatever version of whatever girl someone else wants us to be.

Reading these essays about first best-friendships, abusive boyfriends, toxic bosses, adopted elephants, and what it means to mother and be mothered, I was disarmed by the clarity of Kabeer’s thought, her relentlessness, and her propensity to question—and then question again. “I thought if I stared at it long enough, a solution to my problem would present itself—my problem being nothing more than an indefinable sense of longing,” she writes. The pleasure of this book lies in Kasbeer’s commitment to staring long enough to see what lies beneath the surface of herself.

— Sara Petersen for Guernica

Guernica: I related to so much of this book that sometimes I was almost uncomfortable at how precisely you nail certain aspects of coming of age as a girl in America. But it seems like traditional publishers are less apt to show interest. I’m curious about your experience finding a publisher. And how did you manage to craft your story, and sell it, so that it avoided the typical pitfalls of young white girl memoir?

Sarah Kasbeer: I actually don’t know if it does, although I tried to be as honest as possible about my own privilege and complicity. I do think the publishing world needs to make sure work by marginalized voices gets selected and marketed with the same zeal that has traditionally been allotted to straight white authors. Stories that have historically been suppressed are more urgent to our collective understanding of the world. But it’s our job as writers to find new lenses to examine old experiences.

My book made the most sense as a memoir in essays and was probably always more suited to a small press, although I did first try to find an agent to represent it. I noticed the books it felt most similar were published by independent presses, like My Body Is a Book of Rules by Elissa Washuta and If You Knew Then What I Know Now by Ryan Van Meter. Memoirs made up of discrete essays that function like episodes in a larger story are probably harder to sell, although there are notable exceptions. Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot comes to mind.

I didn’t have a one single narrative, but a cluster of related experiences. The essay format more accurately reflected the snowballing nature of trauma, how I experienced and re-experienced it over time. The recent cultural shift that has put a stronger focus on women’s experiences of abuse and assault definitely helped my book feel relevant. But I always wondered why it was so hard to find books about the ordinary traumas of being a woman. Those experiences would either be a single chapter in a larger memoir—or the whole story, but only if what happened was brutal enough to warrant attention in a culture that is obsessed with—and inured to—violence against women.

Guernica: The end of the book’s first essay, “On the Edge of Seventeen,” which is about an abusive relationship experienced in your teens, really shook me. It’s a deceptively simple line: “He looks like a seventeen-year-old boy.” Reading it gave me such chills of empathy for this character, who is objectively horrible to the narrator. How did empathy shape the way you told this story, which you revisit again in a later chapter about your abuser?

Kasbeer: I had help on that ending from a very good editor! But really, endings are hard to stick, especially for essays like the one you’re referencing, which is about my first boyfriend punching me in the face. It’s hard to write an ending to an essay about a painful thing that happened that you still can’t quite make sense of. There’s an urge to have learned something from it, so you can give the reader a takeaway, but that’s often not built into the actual experience itself. Sometimes it’s just about framing the contradictions, so we can try to understand them.

This was a kid with a violent family history that he sadly did not seem to escape. I can only tell my side of the story, which includes wondering why he did what he did to me. In that way, when I try to empathize with him, it’s for selfish reasons. Women who experience multiple incidents of assault or harassment start to see themselves as the common denominator, but if you zoom out, the pattern is clearly one of misogyny.

I wrote another essay about the same experience through a different lens after Trump got elected, when there were so many takes about trying to “understand” Trump supporters. After watching the debate where he lurked menacingly behind Hillary Clinton, I wondered what life experiences had led so many people to find that behavior appropriate. The only way I knew how to explain it was to examine the opposite—how my own personal experiences manifested themselves in my political life, and what that might illuminate about the other side.

Guernica: “Before Empowerment” details how the desire to be seen can inform female desire. I still think back on some of my early relationships, which were rooted almost entirely in my perverse need to be wanted, and pining for that singular “rush of feeling seen,” as you call it. Objectification, in those days, made me feel powerful and released me from the work of having to self-actualize. It also reassured me, in a way, that I had an identity worth processing, to borrow your language again. What do you think this essay says about young women as not-quite-formed adults, versus what it says about the culture at large? What does empowerment, both sexual and otherwise, mean to you in the context of this essay and in the context of #MeToo?

Kasbeer: God, that essay still makes me cringe. I started writing it to examine my relationship to sex, based on an embarrassing experience with a random guy from my twenties, and ended up staring my fourteen-year-old self in the face. I still carry a lot of shame around the fact that I was a sexual being at that age, braces and all, willing to trade my body for attention and approval. And yet, the ecstasy of my newfound power was all-consuming. I wouldn’t have given it up for anything.

I think becoming aware of the fact that you’ve been duped by the patriarchy is a common experience, and I agree that it’s hard to separate our own desires from those that have been imposed on us. I came of age in the 90s during third-wave feminism, then turned thirty during the fourth wave. As a teenager watching Aaliyah and Britney Spears on MTV, I thought that owning your sexuality was a form of empowerment, and it can be. But what I didn’t understand until much later was how these women’s personas were created, managed, and manipulated by men.

True empowerment comes with freeing yourself from the constraints of a society and culture that have largely been formed by straight white male gatekeepers. As a teenager in the Midwest, I was just happy to move away from conservative values around sexual purity and traditional gender roles. In the process, I unwittingly gave the male gaze too much sway. The #MeToo movement forced me to reexamine some of my experiences, not only because they read as abusive in hindsight, but also because I was trying to trace them back to something that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. And that source, I now realize, is what it means to grow up female in a patriarchal society.

Guernica: In “Apollo’s Revelation,” you include infuriating excerpts of emails you received from your rapist after you confronted him about the rape. Did you copy the emails verbatim, and did you talk to him about it? I know many writers of personal nonfiction grapple with how ethical considerations impact their ownership of their own story, and I wonder what your experience was like.

Kasbeer: When I sent him the first email, I offered to talk to him on the phone, but he didn’t take me up on it. It seemed like a fair thing to offer when accusing someone of rape ten years after the fact. I’m still kind of surprised he responded at all. Three years later, when I pulled the excerpts of the emails for the essay, I understood that they would lose their full context, so I tried to err on the side of making him look better than he came off in the correspondence as a whole. But I also pulled statements that sounded so familiar they could have been said by anyone, anyplace, at basically any time in history—minus the rather egregious use of the word “prolly.”

If anything, using artifacts in personal narrative should strengthen it, since memory isn’t always accurate. In this case, I was going to tell my version of the story no matter what, so why not at least include what I know about his side of it? I never spoke to him again after our initial correspondence. I personally don’t think there are any rules about the stories a writer can or cannot tell. There is only a threshold for publication and the reality that you could be subject to criticism for your choices.

The point of this particular essay was to think through how men convince themselves that what they’re doing is not assault. If you look at depictions of rape in art, culture, and entertainment, it is often linked to desire, which is part of why they’ve become so mixed up in our brains today. You have to actively uncouple them, which I think is what the maxim that “rape is not about sex but about power” is trying to do. But the truth is that rape is often about power for the sake of obtaining sex, and separating the two entirely constitutes a form of denial. As uncomfortable as it is, we need to acknowledge the overlap if we want to address the problem.

Guernica: To me, “One Man’s Trash” is one of the funniest essays in the book. The portrait of your boss, an outrageous fashion editor in cool-as-fuck New York City, was so deliciously Devil Wears Prada, but also a really smart examination of how and why young women are expected to withstand abuse and bullshit at the hands of our employers, particularly within the arts and humanities. And with the surge of Black Lives Matter protests, there have been so many much-needed call-outs drawing attention to toxic, racist work environments. What do you think the next generation of smart, ambitious, young women will do differently when it comes to sexism, racism, and general disrespect and abuse in the workplace?

Kasbeer: I included that essay as a kind of comedic interlude because, while I was subjected to a toxic work environment, I was not targeted because of my identity. The people were just mean. The subject matter has definitely taken on a deeper relevance since I wrote it. I’m all for companies being called out, especially when the values they project are a far cry from what employees experience. It horrifies me to think how much worse my experience could have been if tinged with racism, homophobia, or transphobia.

Creative industries like art, fashion, music, entertainment, and publishing are especially ripe for this type of abuse, in part because the employees are made to feel “lucky to be here,” but also because the powerful decision makers often have their behavior excused because they’re seen to have some “creative genius.” The recent public shaming of companies with toxic work environments is a reflection of the #MeToo movement in that it digs deeper into the small ways employees can be exploited. When I recently watched The Assistant, I was more triggered by the power imbalance—the subtle ways the film’s protagonist was intimidated and degraded in her role—than I was by the larger backdrop of sexual coercion perpetrated by her boss, which was a more clear-cut form of abuse.

Guernica: In “Sacred Stories,” you revisit the story of Jack, your abusive teenage boyfriend from the first essay in the book, alongside the story of your relationship with your father. The illusion of protection plays an important part in both relationships. Jack impressed you with his physical prowess and macho modes of offering you protection as “his girl.” And your father, who made you feel protected and special, not only failed to protect you from Jack, but didn’t own the fullness of his failure until much later in your life. About what we can expect from our loved ones, you write, “Sometimes we’re left carrying our own stories, like oceans inside of us—pasts we cannot kill with neglect like some under-watered houseplant.” So much of love, it seems to me, centers on a sense of safety and protection, but this essay sort of pushes against that idea. Did you do this deliberately, or did this thread reveal itself as the essay took shape?

Kasbeer: I didn’t actively think about this while writing, but it’s funny you should mention it because I’m obsessed with the Jenny Holzer truism, “Protect me from what I want.” I constantly feel as if my desires need to be constrained for my own good. It might stem from this early experience, when I wanted nothing else but a relationship with this guy I knew had the potential to harm me. I have since somewhat tamped down my impulsiveness, but the urges remain.

I think we all secretly want the opportunity to blow up our safe and boring lives, which is what Holzer’s line is getting at. But as soon as we do, we want those lives back unchanged, and for the people who were there to continue to support us as if nothing ever happened. I felt this way a little bit about my parents, but that was also unfair to them—I wanted to have my cake and eat it too, without acknowledging how I’d hurt them in the process. We both carried this pain without talking to each other about it, and that’s part of what this essay mourns.

Guernica: In “Stuck in a Water Well,” you navigate territory that can easily dip into cliche or platitudinous mush, interrogating what it means to mother and what it means to need and want mothering. In both this essay and “Everyone Gets a Dog”—which, in overly simplistic terms, is about your relationship with puppy puppets—I was struck by how you give a light touch to the subject of your own motherhood. Lately, we’re seeing a lot of essays and books about the question of whether or not to have children, but in these essays, that question is almost an afterthought in service of bigger questions of what it means to mother outside of accepted social norms. Did you intend to center considerations of motherhood in these essays, or, as so often happens, did motherhood snake its way in on its own through the writing process?

Kasbeer: Not having children was not ever a debate for me, which is probably why it feels like an afterthought in my work. Although, the idea of being responsible for another person terrifies me, which might have a lot to do with my own life experiences.

I wrote both of these essays with motherhood in mind—first my relationship with my own mother, which was strained at times, and how loving animals helped me cope. Second, my “adoption” of two dog puppets, which brought my inner child some comfort. I was a stuffed animal hoarder as a girl, and there was something about returning to a new variation of that plush, comforting pile that appealed to me. I think motherhood and childhood are inextricably linked, and I was trying to get at that in both essays, with the caveat that I am not, nor do I plan to become, a mother myself.

Guernica: In “Lovers,” you confront your past sexual traumas as they pertain to your sex life with your supportive, loving husband. In this chapter, the narrator feels the most urgently embodied. More than in other essays, you really invite—or maybe force—the reader into the narrator’s corporeal experience. You also include fascinating insights into both sex therapy and individual therapy. It’s so glib to say that writing can heal past hurts or allow us to process our own lived experiences, but it’s true that the exercise of writing about our past selves forces us to maintain some modicum of intellectual distance. Can you speak to what writing this book was like for you, on both emotional and intellectual planes?

Kasbeer: I started the essay “Lovers” in first person and struggled to get anything interesting on the page. When I switched it to second person, it flowed like water. I tried changing it back to first person at the end, but it didn’t feel right, since the essay was about multiple selves. I do think the work of writing about trauma helps you separate it from yourself, and allows you to look at the story more objectively. Writing is a tool for thinking, so to say that it has no role in how we process traumatic events or our lives in general feels dishonest to me. At the same time, you need therapy, or another person who supports you, in order to heal from trauma. I don’t think writing is “healing” in and of itself; in fact, sometimes it’s retraumatizing.

My biggest struggle with this book was how to make it resonate emotionally and intellectually. In the end, I wrote through the feelings as I had them, then edited and analyzed my drafts later to make sure I had captured all the layers of the story I wanted to tell. It wasn’t a quick process, but in the end, it got me where I needed to go.