In 1959, applicants to the University of California were asked to answer an essay question of their choice from a list to demonstrate writing skills. The seventh question was on political philosophy: “What are the dangers to a democracy of a national police organization, like the FBI, which operates secretly and is unresponsive to criticism?”

The query prompted controversy beyond the theoretical safety of academia. An offended “chairman of the Americanism Committee for the 23rd District of the American Legion” saw it, and the news got back to J. Edgar Hoover.

In a chapter of his new book Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals and Reagan’s Rise to Power, author and award-winning investigative reporter Seth Rosenfeld tells the story of what happened next: “Hoover was livid. He viewed the question not only as subversive but as an attack on the FBI—and he took any attack on the bureau personally.”

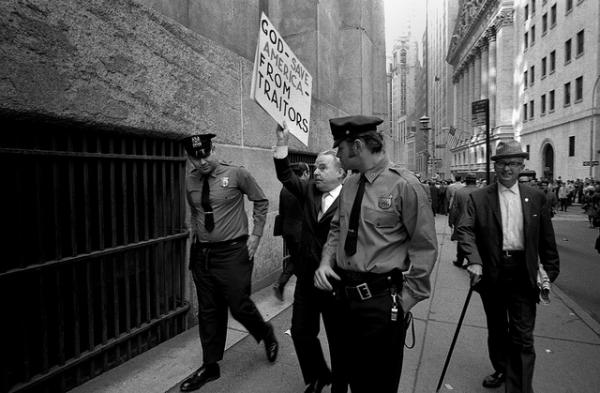

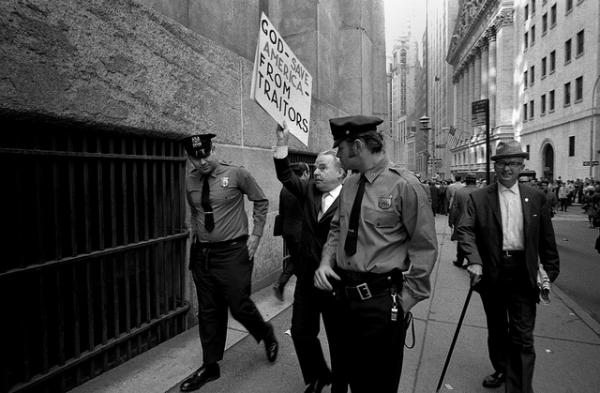

Hoover and his gang began a mission to discredit the University of California. The FBI used a mix of tactics—public relations, intimidation and investigation—to make it clear that the bureau did not take any form of public embarrassment lightly. Agents urged media contacts to publish editorials in Californian newspapers, attacking the university for “allowing such questions;” they pressured the board of regents to reveal the question’s author; and, even after the question was retracted, used the FBI’s secret “Security Index” to investigate the political histories of faculty. They found seventy-two faculty members on the list, which was designed to record information about anyone the bureau considered potentially dangerous to national security. As well as Communists, suspected Communists and Communist sympathizers, Rosenfeld writes: “The index encompassed broad categories of people in labor, civil rights, education, the arts and youth organizations.”

The question shocked Hoover, he wrote, because, “The very wording of it implies that this organization is endangering our historic and constitutionally guaranteed liberties. Students reading this question are being taught to believe something which is entirely untrue.”

And yet, as Rosenfeld makes plain in Subversives, the implications contained in the question were true: the secret operations of the FBI under Hoover’s reign threatened democracy by stifling and interfering with dissent. Since that time, the bureau has tried to keep the organization’s murky past hidden from public scrutiny and criticism.

The FBI’s own documents showed that the Bureau under J. Edgar Hoover had engaged in unlawful political surveillance at the University of California.

For 30 years Rosenfeld fought legal battles to uncover the FBI’s cold-war era investigations at Berkeley and the bureau spent $1 million trying to stop him. In an essay adapted from the book for The Chronicle of Higher Education, Rosenfeld details the struggle for these documents, which took him to the Supreme Court.

In Subversives, he translates the finally obtained 300,000 pages of records into a nonfiction narrative that tells the story of the Sixties student movement; the intimate relationship between Ronald Reagan and the FBI (which led the bureau to act illegally and Reagan to rise politically); and the manic paranoia of Hoover. It is a fascinating tale of power and secrecy with wide and still relevant political implications told through access to insider memos, meetings and maneuverings.

Subversives is the story the FBI didn’t want told. Seth Rosenfeld spoke to me about power and secrecy, and what Hoover would have thought of his journalism.

—Natasha Lewis for Guernica

Guernica: It’s interesting that the FBI was committed to keeping Hoover’s secrets long after his official reign at the organization.

Seth Rosenfeld: The FBI and other intelligence agencies generally depend on great secrecy and they don’t like reporters or members of the public poking around in their files. I have a part in the back of the book called ‘My Fight for the FBI Files’—it describes the five lawsuits that I brought—and in the course of those lawsuits the FBI claimed that all its activities were proper law enforcement activities but the courts disagreed. The courts said, in very specific terms, that the FBI’s own documents showed that the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover had engaged in unlawful political surveillance at the University of California and beyond that had unlawfully tried to get the president of the university, Clark Kerr, fired because FBI officials disagreed with his policies and his political views.

Guernica: That court decision really stood out for me in the book. You write that as of January 19, 1965,“the FBI’s investigation of the Free Speech Movement ceased to have any legitimate purpose and instead came to focus on political rather than law enforcement aims.” Do you think there was a clear switch from law enforcement to political surveillance?

Seth Rosenfeld: Well, the courts said there was “scant” evidence to begin with that there was any federal violation by the Free Speech Movement, but that after that day it was very clear the FBI knew that the Free Speech Movement was not part of a Communist plot but that Hoover’s agents continued to investigate it. The Free Speech Movement erupted in the fall of 1964 in Berkeley and FBI agents immediately began to investigate it and they were trying to find out whether it was a subversive plot. What they discovered was that there were a few subversives—or socialists or communists if you will—involved in it, but it would have happened anyway! Because it was a protest against a campus rule that prohibited students from engaging in political activity on campus. And there’s a series of memos that the San Francisco FBI office sends to Hoover back in Washington expressing that finding. So they had told him three times, as of that date that you cited. And that’s why the courts said from that point on, clearly the FBI knew that the Free Speech Movement was not part of a subversive plot, yet it continued to investigate and moreover tried to disrupt it.

Guernica: Could you talk a bit about the book’s structure?

Seth Rosenfeld: I had acquired some 300,000 pages, and these cover more than a hundred different individuals and organizations and events on the campus during the Cold War period—so from the end of World War II through the ‘70s—and I concluded I could best tell the story by tracing the FBI’s involvement with four main characters: J. Edgar Hoover, Clark Kerr, Mario Savio, and Ronald Reagan. And my research showed that each of those people represented a powerful social force and that they came into conflict with each other at the university during the ‘60s and this clash had great impact not only on the university but on American politics and culture.

Savio represents the early non-violent student movement, outraged about injustice and impatient for change; Kerr is a Cold War Democrat, an anti-communist liberal who believes in the transforming power of education; Reagan is a rising conservative star who uses public anger about the protests at Berkeley as a key campaign issue; and Hoover, the FBI director, is furious about Kerr’s liberalism and his failure to crack down on the Free Speech Movement, which Hoover sees as a communist plot.

Guernica: It almost reads as a kind of theatrical version of the culture wars being played out with characters representing different sides…

Seth Rosenfeld: Yes. I tried to convey that. And after this conflict at Berkeley in the ‘60s the student movement spreads to other campuses. I mean, in truth it was developing elsewhere simultaneously but Berkeley has a huge impact and inspires students elsewhere. So the student protest movement spreads and that has a lot of political and cultural impact and also Ronald Reagan and the conservative movement continue to rise and to spread. Of course, he goes on to become president and the traditional Democratic Party is really fractured by this conflict. It loses people on the left and it loses people on the right as well. And the culture wars continue, despite Obama’s wishful thinking to the contrary. So many of the battles that were played out at Berkeley continue today.

Guernica: Some of the descriptions of actions by the Free Speech Movement, and quotes from Savio’s speeches, remind me of some of the more idealistic factions of Occupy Wall Street. But Savio later suffers from severe depression, which seems to be caused in part by a sense of disillusion that begins at Berkeley. It could be read as quite a pessimistic book.

Seth Rosenfeld: Oh. Tell me why.

Guernica: The students are in a constant battle and being secretly surveilled. Reagan introduces tuition fees to universities in California, and Kerr’s ‘multi-versity’—the impersonal educational bureaucracy—that Mario Savio rails against, could be used to describe most universities in the U.S. now.

Seth Rosenfeld: Well, Savio is a fascinating and complex character. He’s born in 1942 in New York in a very religious Catholic family. He’s raised to enter the clergy and as a young boy and young man he believes he will become a priest. But in high school he begins to question his faith and his dogma. He studies philosophy and science and he applies this kind of skeptical inquiry to his religion and also to everything he sees in the world. And he says that one of the things that really struck him were photos of the Holocaust and he’s shocked that people would have let that happen. And to him that’s evidence of evil in the world and he dedicates himself to fighting evil. Even though he’s breaking away from the church he’s still committing himself to do good in the world and in high school he goes down to Mexico and does some community work down there trying to build an aqueduct and then he goes to Berkeley and he sees the civil rights movement as a way to do good in the world. Savio is not interested in being a politician. He does not enjoy being a celebrity.

Guernica: He really rejects the personality politics that are forced upon him.

Seth Rosenfeld: Yes, exactly, and I think he represents the early student movement in that sense that it was very idealistic and it was issue-oriented. It was not ideological; it was not seeking personal power. And though some of the difficulties he encounters are rooted in his personal history, I think they also represent some of the frailties of that kind of idealistic movement.

In regard to your thought that [the book has] perhaps a pessimistic or rather dark view, I would say the early student movement had a tremendous positive impact. It really opened campuses to being much more involved in the world, it gave students a voice, and it created a space where other positive movements could grow, such as civil rights, such as the women’s movement, such as the environmental movement and American society today is a much more open society. It’s much more accepting of different kinds of people, different sexual orientations, different ethnicities, inter-marriage. And I think that can be traced at least in part to the early ‘60s student movement. But at the same time, the conservative movement has also grown very strong and of course that can be traced to the rise of Ronald Reagan during the ‘60s so the debate continues and it probably always will. I don’t think it’ll ever be resolved.

Guernica: Do you think American society is more accepting of ‘subversives’ — or people who are dissenting now — and especially the kind of lawful dissent that leads to the crackdown portrayed in the book?

Seth Rosenfeld: I do. I think it’s more accepted that students will engage in various protests and I think the public expects that law enforcement authorities will respond appropriately or, I should say, without excessive force. An example of that is the recent occupy protest at University of California, Davis where students were sitting down peacefully and one officer took out his pepper spray and just systematically sprayed each person in the face. And this was captured on video and went all over the Internet and sparked outrage. I think the public is very opposed to violence and they expect the police to investigate violent behavior aggressively.

Society has a need for intelligence agencies and police agencies and those agencies need secrecy and power to be effective, but there’s an inherent danger in that combination of great power and secrecy.

Guernica: And, I suppose—since you mentioned the video—arguably the Internet allows people to be more informed now, if they want to find out what happened at a protest. In the book, the conservatives and students are battling each other for public opinion. Now, video footage can show people what happened, which is a more direct bystander experience. Do you think that has affected public opinion?

Seth Rosenfeld: Yes. In the ‘60s students got the word out through leaflets. And these days they can use text messages and video clips on the Internet. Of course, their opponents, or government officials, can also use those same techniques so there’s much faster and more intense dialogue. One of the things that was very interesting to me in reviewing the FBI files was that I could see how Hoover’s FBI was involved in gathering immense amounts of information, voluminous files, and then how the FBI used that information. So in the case of Savio and Kerr, the FBI used the information to discredit them or undermine them. But in the case of Ronald Reagan the FBI used the information to help him. And I think ultimately the book is a cautionary tale about the dangers that secrecy and power pose to democracy. Society has a need for intelligence agencies and police agencies and those agencies need secrecy and power to be effective, but there’s an inherent danger in that combination of great power and secrecy. The FBI today is a very different organization from Hoover’s organization. There’s much more congressional oversight, there’s much more public accountability. The head of the FBI, Bob Mueller, is a very different person than J. Edgar Hoover. But having said that, there’s still this inherent danger of secrecy and power and the collection and use of information.

Guernica: Those ideas have been debated quite a lot over the past couple of years because of WikiLeaks.

Seth Rosenfeld: Yes. When the government engages in over-classification and withholds so much public information it really raises questions about the legitimacy of its secrecy claims and I think WikiLeaks is a response to that. Certainly in my Freedom of Information Act lawsuits the courts found that the FBI improperly tried to keep voluminous public information secret.

Guernica: You draw attention to the word ‘subversives’ by using it as your title and it is also used again and again through the book. In the book, it seems “subversives” is stretched by the FBI to apply to Communists, Free Speech activists and, eventually, anyone who didn’t fit Hoover’s conception of patriotism. You note that the word was never legally defined, something that served the FBI well because they were able to use it quite broadly. Is that something that was clear to you when you began researching the book or was that something you found out gradually?

Seth Rosenfeld: That came out through my research, through the FBI records and the use of that word in them. And then I learned there was no legal definition of subversive and that no president had defined it and I could see how J. Edgar Hoover took advantage of that to extend his power and his unlawful surveillance activities. And the title is really a double-entendre because it not only refers to subversives as seen by the FBI but also to the undemocratic activities of FBI and its allies, including Ronald Reagan.

Guernica: What would Hoover think if he read your book?

Seth Rosenfeld: If Hoover read my book, he would think I was a subversive. (pause) I’m sure.

Guernica: Do you think the students in the sixties should have thought more about surveillance?

Seth Rosenfeld: When I interviewed Mario Savio, I asked him about the FBI’s investigation of the Free Speech Movement and its efforts to disrupt and discredit it, and he said, we knew the FBI was investigating us but we never expected that they would try to disrupt us and, I’m paraphrasing his quote, but he said that what we were doing was this very Thomas Jefferson thing, this very traditional democratic thing. The Free Speech Movement always met openly, with wide participation, and it was a very democratic process. And I think one of the lessons is, by operating in that way, a non-violent movement can protect itself from being manipulated by infiltrators and provocateurs. So just in terms of being paranoid, if everything is done openly and by consensus and is non-violent then that transparency is a kind of protection whereas things done in secret are more vulnerable to being manipulated.

Guernica: You mention that this openness became a bit unworkable and that the Free Speech Movement developed a steering committee.

Seth Rosenfeld: They tried to strike a balance between possible participation and consensus-making on the one hand and being able to efficiently operate day to day. So the steering committee was a way to do that. But they always believed that any major decision should be thoroughly discussed before any decision was made.

What I learned from doing my research is that the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover was trying to manipulate events and in a sense change history through its covert operations during the ‘60s.

Guernica: And it was people who met as part of the Free Speech Movement who went on to form the Vietnam Day Committee?

Seth Rosenfeld: It was not the exact same set of people but the Free Speech Movement had opened up the campus and made it possible for students to engage in political advocacy and they won that right in December of ’64 and then in May of 1965 you have what is called Vietnam Day, which is a huge teach-in, examining the Vietnam War and advocating for an end to the war. And some of the same people involved in the Free Speech Movement at various levels were also involved in the Vietnam Day Committee, so in both ways it grew out of the Free Speech Movement.

Guernica: So maybe Occupy Wall Street has done the Free Speech Movement’s job and opened things up, and something comparable to the Vietnam Day Committee is yet to come. Another comparison can be made between the Free Speech Movement and Occupy in the way that police overreaction sparked greater participation.

Seth Rosenfeld: Yes, very true. At various points along the way the police overreaction actually fuelled the student movement. And this happened not only with police but with the FBI. That’s why I say the FBI’s dirty tricks helped to fuel the student movement: they backfired. For example, in 1960, there’s the protest at San Francisco City hall against the House Un-American Activities Committee and Hoover concludes that this protest was a communist plot. And he issues a report called ‘Communist Target – Youth’ and he distributes this very widely. But when the students go to trial for the protest they are all acquitted, including Robert Meisenbach who, according to Hoover, had started the whole thing, and this vindication inspired the students. They were outraged that the FBI would issue a report that was contrary to the facts and their outrage grew when HUAC put together a so-called documentary called ‘Operation Abolition’ which supposedly documented the communist operation to abolish the House Un-American Activities Committee. When the students saw this movie they were even more outraged because they could see very clearly that the film had been put together to create a completely false picture and they began to show this movie and do critiques of it and raise money. And some of the students wrote about it, there was a book called Student, which was partly about this protest and all these events. Mario Savio happened to be in a drug store in New York City one day when he was just out of high school and he found this book and it had an impact on him and he thought “Berkeley’s the place for me.” He thought this was a good sign that students would engage in this protest. So that’s another example of Hoover’s efforts backfiring: the film inadvertently winds up bringing somebody who would become one of the most powerful student leaders to Berkeley.

What I learned from doing my research is that the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover was trying to manipulate events and in a sense change history through its covert operations during the ‘60s. The FBI’s efforts now to cover-up its public records about those activities are in effect another attempt to alter history by obscuring the past.

Guernica: And there can’t be an honest assessment of what the FBI’s job is–and what it should be doing and what it shouldn’t be doing–without this dark history being opened up. Have you had any responses to the book from anyone at the FBI now?

Seth Rosenfeld: Well when I was doing some earlier reporting for the book, the San Francisco Chronicle stories in 2002, Senator Dianne Feinstein sent a letter to the head of the FBI, Bob Mueller asking for his response. And he replied in the letter, which I quote at the front of the book and also in the ‘Appendix: My Fight for the FBI Files’ section, so I’ve had that response but the FBI refused to comment while I was doing further research on the book. And there’s been no comment from the FBI so far.

Guernica: It’s interesting. He wrote, “As a citizen of this country, I abhor any investigative activity that targets or punishes individuals for the constitutional expression of their views. Such investigations are wrong and anti-democratic, and past examples are a stain on the FBI’s greater tradition of observing and protecting the freedom of Americans to exercise their First Amendment rights.” And he goes onto say that he is investigating the response to your FOIA requests and he instructed the Records Management Division to “determine whether the FBI redacted information in order to shield the FBI from embarrassment or to cover up unlawful activities.”

Seth Rosenfeld: Yeah and the book seems to have annoyed people on both the left and the right. There was a Wall Street Journal review, which in many ways was very positive but the author complained that I had ignored misconduct by the left. And I disagree with that point. I did describe how the movement became more violent as the decade continued. But this particular author, who had been a radical but is now a neo-conservative, complained that I had not written enough about how, in his view, the movement just devolved into violent maniacs. And on the left there have been some complaints because I exposed one radical activist as an FBI informant, Richard Aoki. So there you go, you can’t make everybody happy.

Natasha Lewis is a freelance journalist from London and graduate student at NYU’s Cultural Reporting and Criticism program. She has written for Dissent.