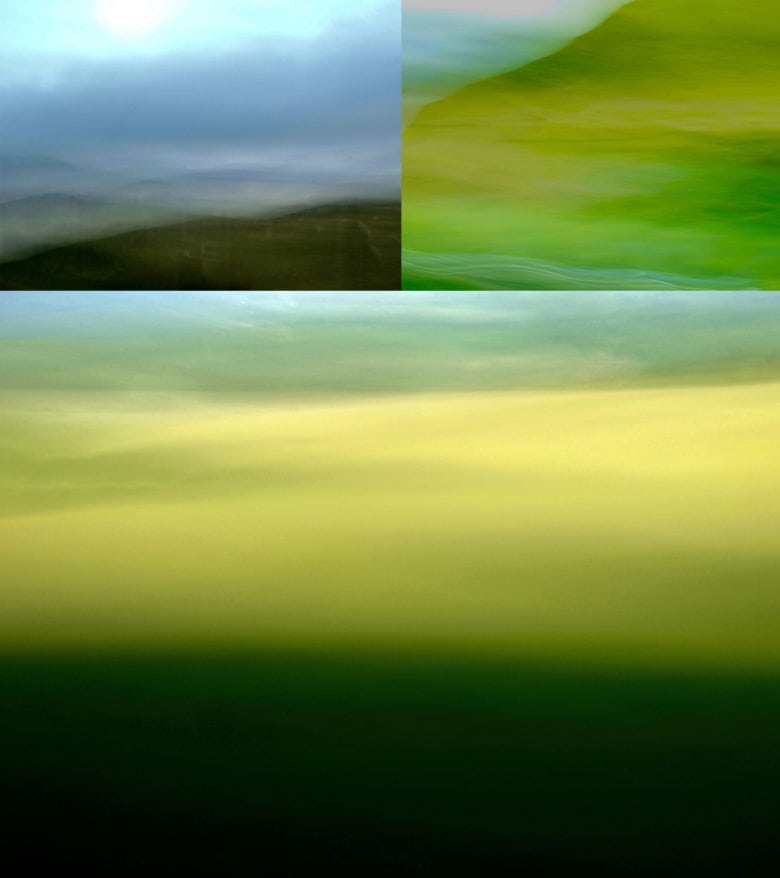

It was late afternoon in late September and the leaves were just the expectant side of peak. Colors of flames and embers; long late-day shadows already pooling into pockets of deeper darkness. The woods of suggestion, metaphor, and fairytales, just beyond my studio door—always infuriatingly out of focus.

This was several years ago, before the pandemic transformed life as we know it, and I was staying at the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire. I was there to write, and write I did, dutifully, all day long. But just before dusk I’d begin to act like my dog when she had to go out. I’d squirm, get up, and pace, eyes wild, needing to do something that my brain couldn’t quite identify. This happened every day, and yet it always snuck up on me.

I needed air, motion, to stop thinking, to start walking, to start looking. Before I burst out of my studio and into the deep woods, I’d grab a jacket and my camera. And then I was free to walk the Colony’s network of dirt roads till a big cowbell called me to dinner.

I felt exceptionally lucky. I was in rural, northern New England at peak “leaf peeping” season, and the reds, yellows, and blazing, glowing-ember oranges of the sugar maples, especially, begged to be photographed. But my shots were almost always out of focus. I suppose I wasn’t really surprised. At that time of day I’d already begun to squint, trying to resolve the fir shadows into rationality and reason. It was the hour that, all my life, I’d casually called dusk.

But there at MacDowell, I began to understand that dusk is not the unilateral event I’d thought it was. It’s more like a process—a slow, silent wave. After my walk that day I did a little research and learned that dusk and twilight are not the same thing. There are three stages of twilight: Civil twilight begins at sunset. During this stage you can still see objects and colors, plus a few stars and planets near the horizon. During nautical twilight, the stars brighten and earthbound objects grow less distinguishable. Finally, astronomical twilight marks the point when the sun no longer interferes with your viewing of the night sky. It means it’s damn dark.

The final moments of each of these phases are called dusk. So there’s a civil dusk, a nautical dusk, and an astronomical dusk. I couldn’t tell you which one I first experienced at MacDowell—in fact, the stages overlapped. Dusk, it turns out, is a relative construct. The edge of the woods might be in civil dusk while the interior was in astronomical twilight. Regardless, when I was tromping around MacDowell’s woods, trying to fix the iconic fall leaves in my viewfinder, I was irritated. I didn’t have a tripod with me, or any serious camera equipment that would have helped in the low light. All I had was my frustration.

On the third day of bad pictures I got angry. As I released the shutter, I jerked the camera up and down, like I could teach it a lesson. I probably looked like some kind of strange, large bird, pecking in the dusk on the edge of the forest.

Actually, it was fun. I did it over and over again.

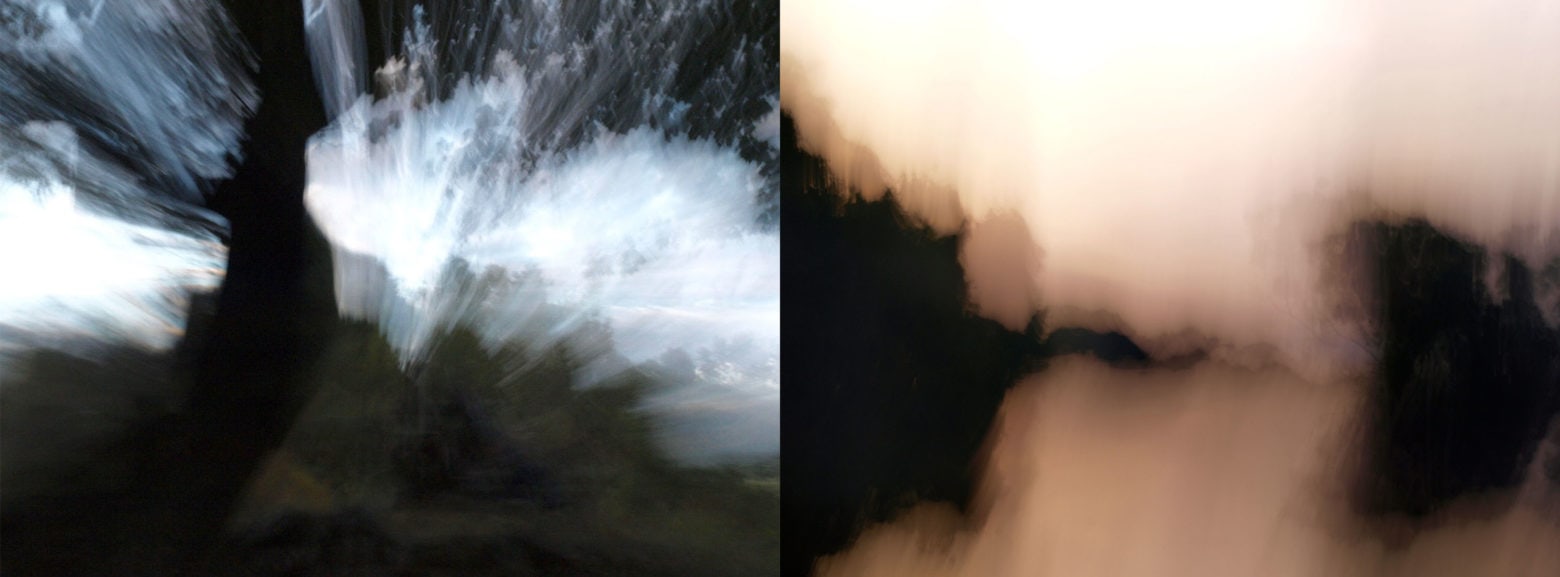

When I saw the results that evening, I was astonished. The images looked more like abstract pastels than photographs. Like I’d wrought some kind of accidental magic with light and motion. I hadn’t taken pictures of what I’d seen, but of the moment my imagination moved in the semi-dark, groping towards the half-obscured woods around me. A moment of fusion rather than focus. A moment “so imperceptible,” as Scottish poet Annie Boutelle writes in her poem “Liminal,” that “one perceives.”

I was hooked. As I traveled, I kept making more dusk pictures: in Oregon, Nova Scotia, the Brazilian Amazon, throughout New England, and, especially, in Wales.

Wales is a small country that takes up a big part of my life. I went to graduate school in rural West Wales, and it quickly became one of the places I feel most at home on the planet. I speak Welsh haltingly; I teach there every summer; and after seven long years I’ve just finished writing a braided memoir about my experience there, called The Long Field: A Memoir, Wales, and the Presence of Absence. It was while writing the book that I learned about the Celtic concept of thin places and times.

I’ll get to that in a moment. But first, I want you to think about the incompleteness of dusk. Like ruins, like puzzles, dusk lets us in. It’s the planet’s original invitation to imagine.

Darkness obscures and sunlight reveals, but dusk—that liminal moment in between—murmurs suggestions. You might be seeing a snake, dusk said to Eve. Or maybe it’s just a branch. What do you think it is?

I think of dusk as the temporal place where seer and seen meet and mingle. It’s the time of day—or is it night?—when the perceived world becomes an equation: Half us, half other. Half human invention, half environmental insistence. A hybrid time. An inclusive time.

This is what I learned in Wales: The Iron-Age Celts considered dusk to be the beginning of the day, the moment of greatest potential. It was what they called a thin time, when seen and unseen worlds overlapped and became porous. (They also believed there were thin places too—the Neolithic megaliths, in particular—where it was possible for mortals to pass into the world of gods and the dead, and vice versa.)

I find this idea of thin places and times most useful in suggesting metaphorical possibilities rather than actual ones. “They appear,” says Irish scholar and curator Ciara Healy, “when the separate worlds we co-inhabit overlap and become simultaneously present in our mind’s eye.” Or, also in her words, “when we are capable of inhabiting more than one worldview at the same time.”

I love that: When we’re capable of inhabiting more than one worldview at the same time.

It is dusk’s quality of thinness that bends our minds toward environmental empathy, and that’s what interests me. In the half-light, the simple task of seeing requires both stepping further into the self—with memory and imagination supplying what our eyes can’t—and stepping away from ourselves in order to more carefully probe the otherness visible around us. Dusk is like holding a yoga pose; you must extend and retract simultaneously. Viewed through this lens, dusk does nothing less than demand our full and wholehearted engagement with place.

Through their semi-abstraction, the “Dusk Series” photos rekindle that very engagement, seizing the viewer’s memory, imagination, and powers of observation all at once.

The dusk photos offer glimpsed liaisons between day and night, observed and intuited, light and dark, seer and seen, subject and object. They render the intangible, tangible and give form to a thin, liminal experience we might encounter every day, if only we’d pay attention. But they do more than shelter the romantic imagination. I see them as emblems of active ecological détente, positing landscape as our partner in a holistic environment. In this context, the dusk photos insist on repositioning the human gaze within the natural world, even while tacitly acknowledging the advent of the Anthropocene through the camera lens that created them.

And yet, they remain photographs. And while photos won’t stop the fires burning in the Amazon, photographic metaphors can be useful as well as beautiful. They can remind us that our gaze is meaningful; it’s not a passive record, but an active participant in a thin process. If we prove capable of inhabiting more than one worldview at the same time—our own and, radically, that of the forest, the pasture, the river, the sea, the sky, the mountain looking back at us; if we can employ imagination and scientific observation simultaneously—then perhaps art has a role to play in, say, galvanizing the fight against climate change. As the journalist/innovator/novelist Jonathan Ledgard has said of the impending challenges of fighting global warming, amongst other human-instigated disasters, “The only possible thing to do is go in an imaginative direction.” And it can begin with something as simple as seeing.

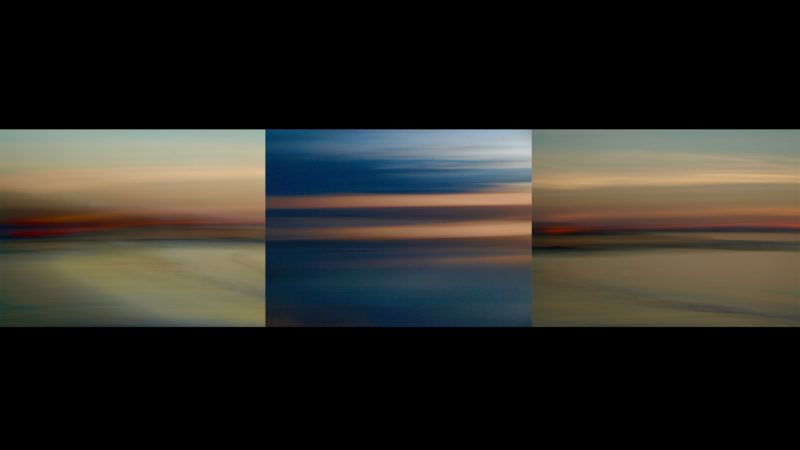

I took the above images from a zodiac craft on the Rio Negro, about two days’ journey upriver from the Brazilian city of Manaus. Some kind of dusk was closing in, darkening the hour’s stillness until the river’s surface shone like a mirror. We could see everything twice—the sky and its reflection; the caiman crocodiles on the beaches and their reflections; the thickly interlaced trees of the riverbanks, shimmering upside down in the river—yet all was disappearing with the fading light. Everyone on that zodiac strained as one with concentration. We were looking fiercely and imagining fiercely—was that a caiman, or a log? A log, or a caiman?—so much so that, whether optically rendered or not, the experience seared itself into us and became more powerful for the uncertainties it provoked. And it sent more than one of us to reference books the next day.

What the dusk images capture from that hour on the Rio Negro that my traditional snapshots can’t is an insistence on temporality. The snapshots preserve a moment and lift it out of time. The dusk images do the opposite: they reveal the passage of time and the searing incompleteness of the experience. The blurred riverbanks blend the rosy ochre of the earth together with the insistent greens of river grasses and trees sheltering on the banks, transforming the planet’s greatest celebration of biodiversity into apparent unity. Paradoxically, that blur snags my imagination and draws me in whenever I see it, rekindling the wonder I felt in the moment, reminding me of the Amazon’s fragility and evanescence, of my fragility and evanescence, and of the space we momentarily inhabited together. A species of perceptual “home” in time and space. A thin place.

All the dusk images speak of time. On the Rio Negro, and in all the places I took these pictures, when I opened the shutter and moved my camera up and down, or sideways, or in circles, digital photography became a process rather than an instant—a process I could only perform in a very small window of opportunity. Each time I went out into civil twilight, it would fade to dusk, as would the next twilight and the next, the world graying and graining and disappearing before my eyes. The darkness always came so fast.

I recognized that, too, as metaphor—one echoed by the blurred images themselves. One thought dogged me as I was taking the photos, and again when I saw them on my computer: If we humans could experience geological time, these photos might be what we’d see in the blink of our lifetimes. And if so, it wouldn’t be the earth’s movement that would register, but our own. We would be the ones in motion, just passing through.

That’s a sobering thought, and it reminds us that while we are here, we have a political choice before us: not about what we see, but how we see. A choice that repositions the human gaze as relational, governed, like the forests and rivers and hills and seas, by the greater forces that rule the planet. As part of a relationship that privileges neither world nor worldview, but dares to imagine both as inhabiting the creative, empathetic space in between. The thin space. If this is a choice we can make and a space we can cultivate, perhaps dusk will again become the beginning of the day.

Note: All images were created “in camera” using only light and motion. They were not digitally altered in any way.