In Mikkel Rosengaard’s debut novel The Invention of Ana (HarperCollins), a young intern becomes fascinated with the artist Ana Ivan and the story Ana’s parent’s have construed about her upbringing. Over the course of three months, Ana talks and the intern listens, setting in motion the novel’s central question: just how manipulative is narrative? It explores the idea that the stories we tell about ourselves and the ones we love mold not only our minds, but physical reality as well—time, space, our bodies—if they are told with enough conviction.

Telling a story is a form of seduction. And like seduction, it is never a one-way street. When we listen to someone speaking, we are already anticipating what is coming, crafting our responses, looking for patterns that might or might not exist. For the past twenty years, poet and critic Kenneth Goldsmith has explored the limits of language by performing vast conceptual poems. His seminal work Soliloquy (Granary Books) is a written account of every word spoken by the poet during one week in 1997. Goldsmith calls the book “an exercise in humility.” The poem is five hundred pages long, yet Goldsmith says hardly anything of value.

Since the 2016 election, literature is often asked to take a political stance. The assumption there is that if literature is to be more than an insular game or empty entertainment, the novel should address political problems, increased racial tensions, the rise of populism. But is this a realistic proposition and is narrative powerful enough to change reality, as Rosengaard’s novel implies? Or are we forever limited by the constraints of language, as Goldsmith’s poetry suggests?

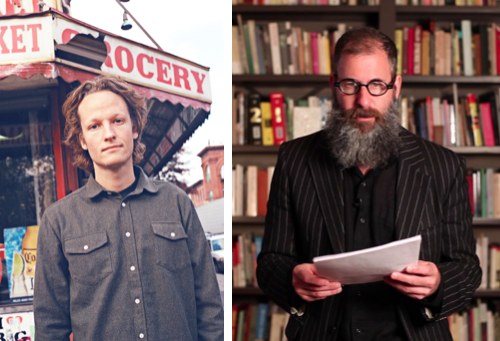

To gauge the limits of telling and listening, we met at a restaurant in Brooklyn on an unseasonably warm February day. We had never met before and had planned nothing for our conversation. What follows is an idealized version of our jagged, uneven, imperfect talk: the kind of discussion we would have liked to have if listeners only listened, talkers only talked, and the only motive for conversation is understanding what the other has to say.

Kenneth Goldsmith: So tell me about Ana. Why did you decide to tell the novel through a narrator, and not through Ana herself?

Mikkel Rosengaard: The first editor who worked on the novel asked me the same question. I couldn’t tell the story from Ana’s perspective because I wanted to write a novel where the protagonist wasn’t a person, but a story or anecdote that is a kind of Don Juan character who seduces everyone it meets. In the novel, Ana’s parents make up a story about their daughter’s life and upbringing, and this story spreads from Ana’s parents to Ana, and then to Ana’s fiancée and an intern working for Ana. I needed several layers of storytellers and listeners who got seduced by the story. That was the idea. To see what happens when a powerful story spreads through a string of lives.

Kenneth Goldsmith: I often get the feeling that today everybody’s got to have a story. A story of their life. I have a 12-year-old, and he is into the rapper Macklemore. His concerts are so different from the ones I grew up with. Macklemore gets intimate, he tells the story of his life. The performer has to connect with the audience, with the Instagram person, and there’s always some sort of story of redemption. It’s like the whole culture takes its cues on how to act from those TV profiles they do during the Olympics. There’s always some tragedy behind the athletes—they didn’t get the gold last time, they broke a leg, they had an abusive relationship—which they overcome to end up in the Games. I think this tendency grows out of a culture of inspirational narratives, like on Oprah, where everybody’s got to have a tragedy and then overcomes it to get redeemed. And we all applaud. Redemption is the new authenticity; without it, you’re a fake.

Mikkel Rosengaard: Yes, and the new thing is that just a decade ago you needed a TV show or publication platform to tell that story of redemption. Today all you need is a smartphone. Making up a story about who you are has become democratized. That is a radical change.

Kenneth Goldsmith: Yeah, money is not the thing that makes you anymore. Now we’re up in the stories.

Mikkel Rosengaard: That means we have a narrative economy. And if that’s true, that means the art of telling stories is more important than ever. I was at the artist Rachel Rossin’s studio the other day, and she was telling about how as a teenager she saved up for college by designing web-pages. And very early on she discovered that she couldn’t get any work if her name was Rachel and she was a 15-year-old girl. So she made a new email account, called herself Robert and pretended to be in her thirties, and then the jobs started flowing in. With the internet, the story and image we conjure up about ourselves comes before physical reality. You can create and project any image you want, and then become that image. There is something very subversive in that.

Kenneth Goldsmith: It’s all Warholian. The reason we still care about Warhol is that he was completely right. Everyone can create a story of themselves and become famous for fifteen minutes, the way YouTube stars are manufactured. But that also makes it more difficult to gain sustained attention, especially after the election, which felt like the end of culture, the end of art. Culture is so fucking muted, I’ve never seen art and books so dampened down. People are just so freaked out, and rightfully. It’s like art feels extravagant, almost frivolous, compared to the political troubles we are facing. You can’t make this shit up.

Mikkel Rosengaard: And what’s your response to that as a conceptual poet? It can’t get much more artsy than that.

Kenneth Goldsmith: It’s a bad time for poetry, as Brecht says. I think we’re in a moment of neo-social realism. The only work that gets any heat is the work that directly addresses the political situation; anything that falls outside of that is considered noise, not signal. The only ones who seem to have the wherewithal to address this properly are the late night comics. They’re living it, grinding it out, day-by-day in urgent ways that art simply can’t touch. Art is long and quiet. It fails when it attempts to address what happened this afternoon. Art’s response reminds me of the 1930s, when the political problems were eerily similar to what’s going on now, the rise of fascism and populism. But populism in art, as a subject and aesthetic theory, is often equally conservative as that which it is critiquing, and rarely moves outside of its moment. Social realism is manipulation and documentation first, art second. Important, but not important as art. What survives is ambiguity, and the art of today has no patience for ambiguity. It’s very short-sighted and rather ineffectual. There are ways to change the world; art is not one of the better ones.

Mikkel Rosengaard: The problem with social realism seems to be a tactical one. The average American spends ten hours every day looking at a screen, immersed in social media and entertainment produced by extremely efficient corporations. In a world like that, social realism seems inadequate. Did you see the last Berlin Biennial? I thought that was a very interesting approach to dealing with this corporate beast. The curators, DIS, had taken all these corporate marketing tools that are normally used to seduce consumers and used them as subversive tools.

Kenneth Goldsmith: DIS jams capitalist systems by turning them against themselves. You never really know where they stand, which is the type of ambiguity that I spoke about earlier. That’s why the biennial was so despised. People found it complicit in a time when if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. DIS is perverse and perversity—as opposed to perversion—is a rather difficult and complex thing to grasp. Instead of trying to comprehend, it’s simply dismissed.

Mikkel Rosengaard: Exactly. To me, the biennial employed a very effective populist strategy, using novelty to their advantage. Why would you produce a giant cut-out of a headless Rihanna? Or why make a virtual reality piece? Because it creates a spectacle, it brings in people who just want to try this new gadget or snap a photo for Instagram. You’re bringing in an audience who normally wouldn’t go to an art biennial, but while they are spending time there, they’re being exposed to all this radical art work. In that way, the biennial was using consumer desire to drive change.

Kenneth Goldsmith: And they got killed for that.

Mikkel Rosengaard: Yeah, but I loved that. If you want to introduce people to new ideas, or even just plant a tiny little seed in the mind of someone who is not already an art or literature acolyte, then you have to use the same tools as the corporate machinery. DIS dressed the biennial up in this sleek, consumerist armor—and with that armor you can plant seeds for change. I think fiction could really learn from that. Fiction should try and co-opt some of those tactics.

Kenneth Goldsmith: And where—historically speaking—is the precedent for that is in fiction?

Mikkel Rosengaard: To me, the big hero is Manuel Puig. His novels are usually set in politically oppressed realities, the protagonist might be a woman living in an abusive marriage in an impoverished town on the pampas, or a gay man incarcerated by the Peronists for his homosexuality. To survive, Puig’s characters escape their bleak realities by delving into fiction. They go to the movies all the time, they read romance novels, they disappear into fantasies of celebrity culture. A big chunk of his novels unfold inside the glittery fictions that the characters watch and read and recount to each other. A way forward for the novel could be a novel that takes internet culture seriously, or deals with the very real effects social media and other virtual worlds are having on our lives.

Kenneth Goldsmith: That reminds me of American Psycho and what Brett Easton Ellis and that group were doing in the 1980s, which was a precursor to what DIS and groups like GCC are doing.

Mikkel Rosengaard: But the problem with Ellis and that brat pack group of writers is how they don’t point towards anything other than consumerism. In that way, their irony is a dead end. I agree that we have to co-opt some of the tools of popular and internet culture. But it’s not enough to use those tools to just say that capitalism is evil, or to point out how consumer society is all shallow and phony. We all know that. We have to reach for something more, point to ways out. Or maybe try and formulate positive visions, in a humble way, of course, knowing that we are likely to fail.

Kenneth Goldsmith: That’s interesting. I’d like to see that in literature a little bit more. What do you think that would that look like?

Mikkel Rosengaard: It could maybe look like what Roxane Gay did in Law & Order: The Complete Series, and Carmen Maria Machado did in Especially Heinous, where they re-imagined several seasons of Law & Order. Or maybe like the first half of Alexandra Kleeman’s You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine where the novel delves into the tv-shows and commercials the characters are watching. Or I don’t know, Fifty Shades of Grey re-written by Arianna Reines. If we live in a reality where every serious alternative to consumerism has been repressed, and where popular culture is dominating all aspects of our lives, then the novel cannot go against popular culture and consumerism. It has to go through it.

Kenneth Goldsmith: Well, at this point, I don’t think art and poetry and literature is the place to affect change. The beauty about the resistance of art is in its inability to do anything. In a culture that is so held back on capitalism and production, if you enter into a political discourse, you’re going to lose. You’re going to lose to the trolls, you’re going to get hung by the right, and you’re going to get eaten by the left. Those people are really juiced and they know how to use tools and they have tons of resources and they’re really, really effective. I think artists’ resistance should be the opposite; it should come from stasis, through radical non-compliance. As Auden famously said: poetry makes nothing happen, which is its strength. I love that idea.

Mikkel Rosengaard: I’m not so sure literature is unable to make anything happen. Today, with our devices and the internet, it is possible to make up a story, project it—and then become that story. That’s what I’ve been trying to show with The Invention of Ana. The stories we make up can materialize, become reality. And that makes storytelling extremely powerful.