By Tara Isabella Burton

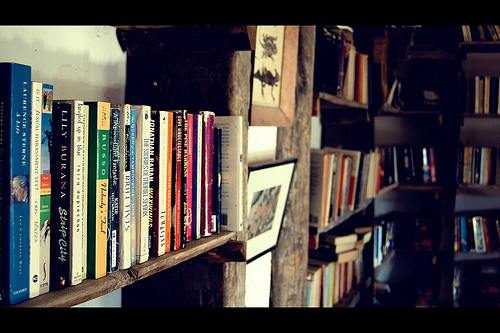

The books are everywhere: cheap paperback copies of Hardy and Durrell, smelling of vanilla; midcentury spy thrillers; Jurgen Moltmann’s three-volume study in systematic theology.

Kemal has piled them up in the doorframes. He has scavenged wood from a deconsecrated church and from it made lopsided shelves that line the equally slanted walls. The courtyard overflows with Hellenic detritus: roof shingles, broken shutters, sculpture-heads, sheared Roman stone. Only the sign out front—a dubious-looking owl advertising “Books Old and New”—indicates any sense of order.

Soon, Kemal tells me, the house will be rebuilt. It will look just as it did in Antalya’s glory days, when the Greeks ruled the city. There will be bougainvillea in the courtyard and icons on the walls. He has gathered mounds of tiles, mosaics, stone—anything he can find to help him with his project. Ataturk, he insists, has destroyed all that is beautiful here, and profaned the altar of the past. Never mind, he says. Byzantium will rise again. In the meantime, would I like to buy a book?

He writes down the name of a treatise on the Victorians: a celebration of archconservative sexual morality. That will suit me best, he says.

I ask him where he gets his supplies.

“From the dustbin.” His laugh is long and loud. “Like Trotsky says–the dustbin of history!”

He asks me what I am reading.

“The Radetzky March, yes, yes.” He approves. “In that case—” he bustles around the room, snatching at books, upending piles. He finds another Joseph Roth for me, then something by von Kleist. When he learns that I live in Oxford, he produces Iris Murdoch’s The Unicorn. (“A Cambridge woman,” he tells me proudly, “Newnham College.”). He pauses; he considers. At last he insists that the shop-boy—a gangly, unwieldy youth with eyebrows that burrow together like larvae–fetch him a pen and paper. He writes down the name of a treatise on the Victorians: a celebration of archconservative sexual morality. That will suit me best, he says.

At no point have we talked about price. Kemal perpetuates fiction that this is not a bookshop. It is a personal library–it soon becomes clear he has read every book in the shop–a sanctuary of scholarship in Kaleici, the city’s touristic heart. He is not a merchant. Rather, he is an intellectual—why, just now he is reading a newly released biography of Nietzsche (in the original German, he makes sure to add.). The Turkish summer is sultry and stifling and sweaty; he would far rather stay indoors. The cat provides sufficient company. Her name is Justine, “After de Sade,” Kemal explains.

He decides that my taste in books in acceptable, and calls for watermelon.

He decides that my taste in books in acceptable, and calls for watermelon. It is improperly prepared–the shop-boy has sliced it with insufficient delicacy—and so he lets loose a torrent of demotic curses, accusing him of all manner of frailties.

To me, however, Kemal is unfailingly polite. He demands to know where I was born, what I am doing here, where I am going next.

“Cappadocia?” He strokes his chin, then his fingertips, then Justine. “You want to see the Christian caves?” He scoffs. Would that I could see Cappadocia as it was! But the best of the frescoes have long been destroyed. “But the Seljuks” he spits “They do not understand what is holy.” They have whitewashed the saints and scratched out their eyes.

That this happened centuries ago is immaterial; for Kemal, the wound is still fresh. He is, he makes clear, Turkish in name only. Spiritually he, like many Christians here, considers himself an heir to the Greeks.

I must go to the east of the country, he tells me, where there are still traces of Byzantium. “It is better in Anatolia,” he says.

I must go to the east of the country, he tells me, where there are still traces of Byzantium. “It is better in Anatolia,” he says. People are friendlier there. They know to honor their household gods. He makes me promise to go visit Caesarea, where several of the church fathers once preached. And, of course, I must visit the city that was Trebizond, on the Black Sea.

“There is a monastery there,” he says. “On a cliff. Many frescoes. One of the few they have not destroyed.” There monks will bless me; there I will find peace. He tells me to read The Towers of Trebizond, the story of an Englishwoman who grapples with her Catholic faith. It will be most instructive, he says. He writes down the address of a Greek inn in the heart of Mustafapasa, a sandy village in the heart of the Anatolian plains, now occupied primarily by cows.

Without warning, Kemal informs me that he is closing the shop for the day. It is almost sundown, and there are still a few hundred unread pages in his biography of Nietzsche. He snatches back the watermelon. He demands an astronomical sum for the books.

I pay it without haggling.

I go east, as I promised him. I walk five miles in the Anatolian heat to Mustafapasa, where I find that the Greek inn has closed down months ago. I go to Caesarea—Kayseri, as it’s now called—an insalubrious conglomerate of tower blocks and bus stations, stinking of gasoline and grease. Trabzon, now an oil-skimmed seaport, seems to be primarily inhabited by Ukranian prostitutes. I go to Sumela, the disused monastery on the cliff, and look at the frescoes of the Dormition, where Christ cradles the infant soul of his mother in his arms. The silence echoes off the cliff-side; there is graffiti carved into the outer wall. I spend two hours stranded in the gift shop, eating lentils and waiting for the driver to return.

But Kemal remains in Antalya, in the old Greek house just past Hadrian’s Gate, Justine arching her back against his ankles. There he scribbles notes on Nietzsche, orders and reorders his books, barks obscenities at his servants. There he overturns the dustbin of history, and dreams of Constantinople, and rebuilds, one tile at a time, the glory of Byzantium.

Tara Isabella Burton’s work has appeared or is forthcoming at The Spectator, The New Statesman, Guernica Daily, The Rumpus, Lady Adventurer, and more. She is the winner of The Spectator’s 2012 Shiva Naipaul Memorial Prize for travel writing and the author of the novel A Thief in the Night, currently on submission. Tara is represented by the Philip G. Spitzer Literary Agency.