Tavares Strachan is a conceptual artist, I suppose, though the phrase seems a little anemic to me in the face of his actual work. He once took a trip to Alaska, cut out a four-and-a-half ton block of ice from a frozen river, FedExed it to his hometown of Nassau, in the Bahamas, and put it in a solar-powered refrigeration unit on the grounds of his childhood school. He followed the route of Matthew Alexander Henson and Robert Peary’s 1909 expedition to the North Pole and planted a flag of his own. He underwent cosmonaut training in Russia, and launches rockets he’s made with beach sand glass and sugar cane fuel under the auspices of the Bahamian Aerospace and Sea Exploration Center in the Bahamas, another of his creations. Last year he put a barge in the river in New Orleans carrying a massive pink neon sign that read, in elegant cursive script, “You belong here.” He meant it more as a provocation than a comfort.

Strachan studied art at the College of the Bahamas, then at RISD, where he made the shift from painting to more conceptual work, particularly in glass, and went on to a sculpture MFA at Yale. In 2013 he represented the Bahamas at the Venice Biennale, the country’s first pavilion there. His new show, Seeing is Forgetting the Thing that You Saw, at Anthony Meier Fine Arts in San Francisco, closes this week. In it he addresses a concern that’s central to his work—invisibility. Here it’s embodied by the chemist Rosalind Franklin, whose research long went unacknowledged but was integral to, most notably, James Watson and Francis Crick’s discovery of the DNA helix. Franklin died young, only 37, of cancer, and so was excluded from the Nobel Prize (it’s not given posthumously) that Watson, Crick, and Maurice Wilkins were awarded in 1962.

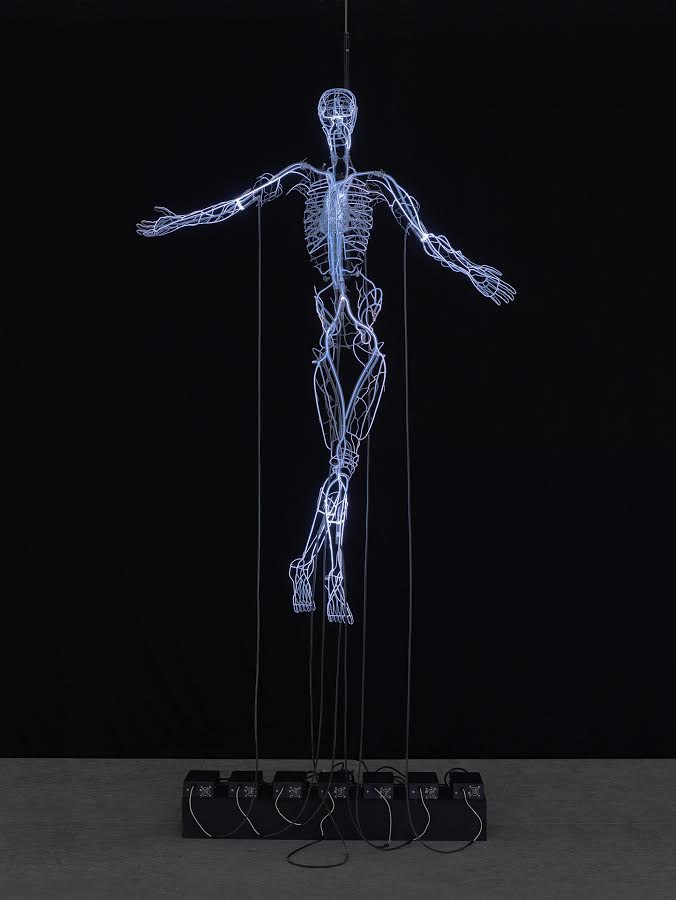

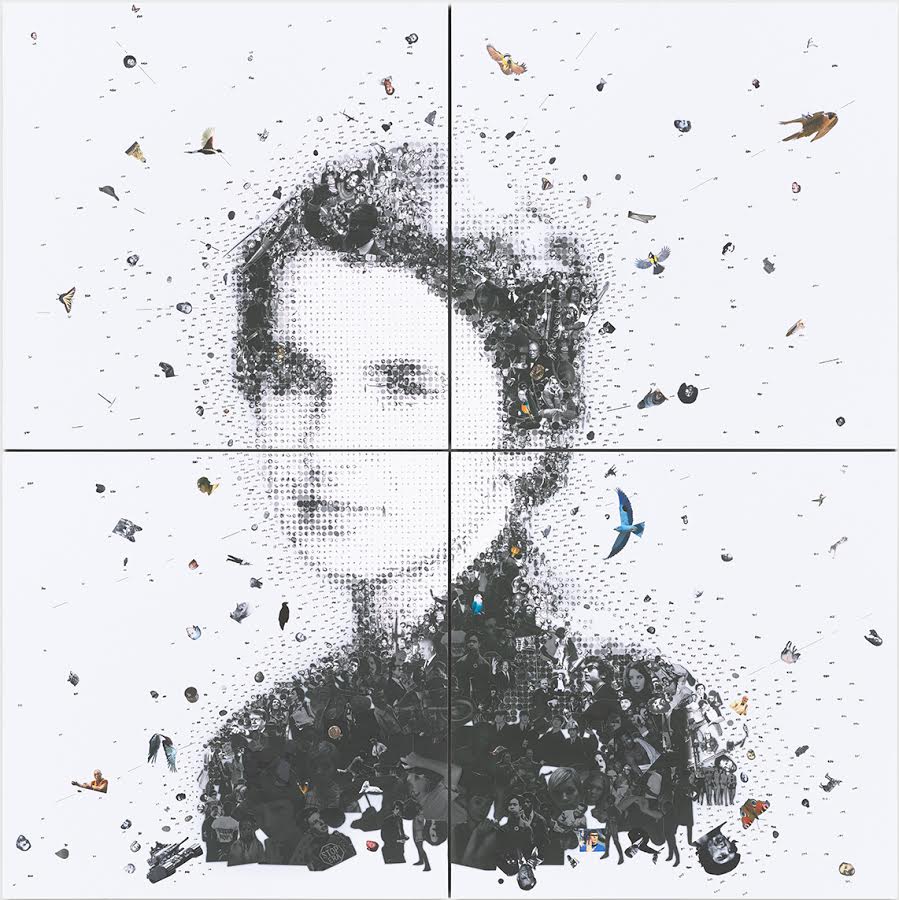

In the center of Seeing is a life-sized neon recreation of Franklin’s circulatory system, and it’s accompanied by, among other works, a series, “The Invisibles,” comprised of objects that were meaningful to her. They’re rendered partly transparent themselves—a cricket ball and bat (she was an avid fan of the sport), a pair of nurse’s shoes (she included her nurse in her will), a microscope. Strachan and his team have also created a massive, 2000-page encyclopedia of invisible people, places, groups, and things to accompany the show, a chronicle of some of the many gaps in our collective history.

The sum of these parts is a kind of portraiture all its own–one that embraces the vagaries of history and memory instead of shying away, or trying to out-muscle them. The brilliance in Strachan’s Franklin isn’t representational, it’s mimetic. We’ve got to find our own way of putting the pieces together, deciding what’s important and what will, inevitably, be left out.

We met on a sunny afternoon on the roof of SoHo House in New York, overlooking Ninth Avenue, to talk about this invisibility, how growing up in the Bahamas has shaped his work, the fungibility of history and narrative, and the role of the internet in dismantling colonial legacies.

—Ed Winstead for Guernica

Guernica: When did you first come across Rosalind Franklin? What was the attraction?

Tavares Strachan: In the studio we’ve been working on this intensive research project about amnesias in society. How society can choose to selectively forget major chunks of its own history. I think it’s quite an interesting psychological and social experiment. How people who have done such critical work in their own specific fields can be totally missed or left out or slighted, or remain invisible in some way. I think it’s something that’s in the consciousness of all of us at the moment, because there’s so much information and access. The question is always, “What are we missing? What are we not seeing?” We came across her doing research on this general subject matter, and started seeing these narratives that sort of jumped off the page.

Guernica: This seems like kind of a shift–from aeronautics, space travel, the North Pole to a chemist.

Tavares Strachan: I think it’s more of a pivot; it all has to do with invisibility. So much of exploration is about a kind of narration. There’s no empirical truth about exploration. You’re still relying on a narrative; not everyone’s going, right? So there’s still going to be the story of a journey, some pictures. When I was actually doing all this research surrounding exploration what was fascinating for me was finding people who were explorers who I didn’t think were explorers, or who were interested in exploration. I think there’s a certain brand, a certain explorer brand, a pretty tight-knit brand. Whether it had to do with gender, economics, demographics, etc., I thought, oh shit, what else could be? The exploration side of things connected with the social, political side of things.

Guernica: Did you develop a personal attachment to Franklin? One thing I’ve noticed about biographers, for example, is they always start calling their subjects by their first names. Did you develop that kind of connection?

Tavares Strachan: Yes and no. I think yes, because of the amount of research we put into it. I think no because Rosalind is a metaphor for the ideas. The idea of the misunderstanding or the mistake or the thing that’s been left out. And I think that idea translates across borders and genres and media.

Guernica: Were there things about her particular case that stuck out to you?

Tavares Strachan: Yeah. I think it was hard because, in our research, there weren’t very many cases like Franklin’s. She was working in the UK and most of the research we were doing was based in the Americas. We started digging into her story and realizing how impactful she was. Who gets to retell that story? And how is it retold? And how does that relate to how it’s told now, by popular culture?

Guernica: So it’s filtered through the lenses of both individual memory and then collective memory.

Tavares Strachan: Yeah. It’s where fiction and nonfiction collide. Things do happen. What we don’t know is how they happen. Things occur, there’s no way around that. Things are happening all the time. I think the how is interesting, and crucial. There’s a sense of Einsteinian logic about process and time; there’s no beginning middle or end, just that it’s happening. That way there’s no triumph, there’s no winner or loser.

There’s something about people not paying attention. There’s opportunity there.

Guernica: Speaking of narrative, I wonder about what you like to read. The encyclopedia made me think of Borges.

Tavares Strachan: I don’t know what writers think about this, but it’s something I think about all the time in art making. When you go from a natural history museum to an art gallery, one’s represented as more responsible, and more accurate; why is that criterion important, why does it matter? It’s something being represented as raw truth versus something that’s a little bit more casual in its relationship with truth. I think there’s a certain decomposition and displacement of how important narratives are. The narrative is actually the truth component of things. Not necessarily whether what the narrator is discussing is important; it’s whether that narrator is a good artist. Whether he’s in a natural history museum or an art gallery, and whether he’s writing about algae blooms or airplanes that fall out of the sky, it still comes down to how that story’s being told.

Guernica: The best story’s the one that wins?

Tavares Strachan: Exactly. And I think to extend that even further; the one that wins, yes. But the one that is artful. Even the ones that win, the blood and guts one, they’re still like the snake chasing its tail. Time will eventually expose them.

Guernica: It needs to speak to another, broader narrative.

Tavares Strachan: Yeah. Something that’s a little more abstract, a little more honest about the condition, a little bit more aware, which is hard to do through history. If you are aware, then I think that’s the true genius of your work. If you can somehow be aware of these unknown unknowns, as Rumsfeld would say.

Guernica: I love that phrase, the Rumsfeld phrase. There’s this word I ran over years ago, I think in a piece that Errol Morris wrote in the Times when he was working on the documentary on Rumsfeld, it’s a word I loved. “Anosognosia.” It’s the medical term for someone whose disability prevents them from knowing they have a disability. Like, you’re too stupid to know you’re stupid.

Tavares Strachan: Oh, I love that. I love that. I think this is where the word entertainment comes up for me. In most of contemporary life, and even before now, I think a lot of our activities are based around pure entertainment. So, yeah, no shit we miss a lot of things. Right? Because, you know, something that’s entertaining doesn’t always make sense. Boring things get walked over. It could be more important and more relevant, but who cares? The turnover of data is so high now, of stuff. Ideas, material. More people, means of production.

Guernica: Do you feel less empowered in the face of that? Or do you feel any compulsion to work within that framework? To try and shape things with an eye toward attention span, or toward a narrative that’s maybe more entertaining? Launching a rocket is something that’s…

The business people need to organize it however they need to organize it to make it make sense to them, but to me it’s always one work.

Tavares Strachan: It’s hard, it’s hard. What you’re saying is really difficult. I do feel empowered, because there’s something about people not paying attention. There’s opportunity there. You can catch a lot of people off guard; the bare face of their distraction, those ten other things. But I do think as an artist you’ve got to decide what your position’s going to be. I’m not an entertainer in a conventional sense. I don’t think I make particularly boring things, but I don’t know that I’m trying to compete with someone who’s in the entertainment business. However, at the same time, I think it’s important for artists’ ideas to be heard and represented. And there has to be a way for you to communicate with a wider crowd of people, because you might as well work in a cave otherwise.

Guernica: So the Rosalind Franklin show, more specifically—the first thing that jumps out at you in the space is the skeleton, and then all these ancillary objects, things that speak to her personality, her loves, her interests, they come into focus. Do you view it more as taking all of these things in the ether around her and pulling them together, or taking her apart piece by piece?

Tavares Strachan: I think it’s a disembodiment or displacement. It’s all one work for me. That’s how I look at it. The business people need to organize it however they need to organize it to make it make sense to them, but to me it’s always one work. The pieces get separated and find different homes and however that works out is how it works out, but for me it’s one work. It’s like looking at paragraphs in an essay. It’s a good question, though. I think it’s doing both. It’s kind of coming in on certain works and expanding outward in other works, and I mean that physically and conceptually. Like the light spreading into the rest of the room.

Guernica: The skeletal figures are very much a recurring image—the Sally Ride, especially, was very similar to this Rosalind Franklin figure. I was interested in the differences in the ways they’re posed. The former seeming like she’s being pulled up by the waist, and the Rosalind Franklin, she’s got her arms out but her feet are crossed. It’s a very Christ-like stance she’s in.

Tavares Strachan: Yeah, kind of Medieval.

Guernica: What was the thought process there?

Tavares Strachan: I was looking at a lot of El Greco paintings, sort of channeling that as a lens for processing sculpture. I was thinking about a kind of levitation, these sort of chandelier figures that exist; painting with light and space. And I think there’s a certain kind of dynamic in religion that I’ve always found interesting, because I think there’s a science/religion overlap happening nowadays, where one’s replacing the other, where we believe what the doctors say without a question. We believe what the scientists are telling us, mostly. And I think that overlap is quite fascinating. To combine those two—energized gases and a deity-like figure—somehow made sense to me.

Guernica: The most poignant example of that overlap, maybe, would be global warming, which you’ve addressed in a lot of your work. The science, we believe it—well, a lot of people don’t believe it—and that’s overlapping with all the mythology of the flood.

Tavares Strachan: And the propaganda, also. The pomp and circumstance and theater. The Al Gores. I think all those things are interesting. The hoopla surrounding the narrative; it comes back down to that. The past hundred years, how many things were truths, even in religion, that are no longer? The Pope is talking about how gay people can get married, and he’s cool with that. It’s an interesting time, for sure.

Guernica: Where do you see the thread leading after this? Are you going to keep exploring the sciences?

Tavares Strachan: Like I said, it’s all one work, man. Different undulations, these ideas, but I think it’s all one piece. Even the works before this one. And I think this is the case for every artist. It’s nice to think about it as an evolution, growth, but the source is the same, where the ideas are coming from.

It was very impactful for me to grow up on an island that functions as invisible to the world from a lot of perspectives. It’s only visible as a sort of tourist destination, for the most part, and I think that’s really interesting. Again this idea of what we’re missing when we look at a place. I think that’s quite a potent chunk of information in relation to the idea of an island. An island that’s quite lush and beautiful, and what does that mean in relation to the rest of the world? How it can be made one-dimensional, and how it can seen in terms of the culture and experiences.

It was very impactful for me to grow up on an island that functions as invisible to the world.

Guernica: Defined as the place, and not a place where people live.

Tavares Strachan: Yeah, exactly. Or an escape for other people. But the people who live there, they’re not really relevant. That’s how I grew up.

Guernica: The encyclopedia that accompanies the show—do you see it as a part of the show, an extension of it, or something else entirely?

Tavares Strachan: It’s a part of the idea behind the show. So we started doing all this research on all these narratives, and compiling this research, and we realized we’d ended up with all this stuff that wasn’t included in encyclopedias. And then we started working with printing and painting and thinking about erasure and different ways to work with these histories. So, again, that the viewer would be left with that question about what they are not seeing. Clearly you’re seeing an object with certain dimensions and a certain amount of color, but what’s missing?

Guernica: Who else is in the encyclopedia?

Tavares Strachan: Oh, my God. It’s a 2000-page document, so that might give you a sense of what we’re doing. Scientists, like Robert Henry Lawrence, one of the first NASA guys. Tribes, indigenous tribes, Arawak Indians. There’s all kind of shit in there. Groups, objects, curiosities.

I think this document needed to exist on some level, for me at least, so we started making the thing. I didn’t have that book when I was growing up. No one really cares about these things that have been left out, but I do, so I made it.

Guernica: Once you start looking at the empty spaces and finding things, it’s like with the space telescope; the next impulse is to look at the dark spots between those things.

Tavares Strachan: Yes, exactly. And have that curiosity generate more ideas and more thoughts and more opportunity. Because then the world is not so bleak, from that perspective. You can see opportunity in those in-between spaces. And for people who don’t have a lot of opportunity, or are from a culture that’s seen in a particular kind of marginalized way, it becomes interesting.

Guernica: Do you think invisibility has, in the modern context, become a kind of power as well?

Tavares Strachan: These are all these niches right now, you can just fit into these cracks. So yeah, it does have its merit. The old school modes are shifting. Things that people care about don’t matter as much as they did even 20 years ago.

Guernica: You think that speaks to religion?

Tavares Strachan: Yeah. The Pope came, saying all these things because he knows they’re going to fall apart if he doesn’t do it. That’s where the world is going, so what’s he going to do? Ignore it? I think that’s the easiest way to make the church irrelevant.

Guernica: The immutable and the pragmatic coming together.

Tavares Strachan: It’s still a business. What are you going to do? Go out of business? Not really.

Guernica: Will the encyclopedia be digitized?

Tavares Strachan: It is already digitized. Whether I’m going to have it accessible digitally I don’t know yet, but we’re almost done. But done… well, what does that really mean? This volume will be finished.

Guernica: Are you explicitly labeling it “Volume One”?

Tavares Strachan: No, I’m not doing that. It’s a springboard for thought, not necessarily to be taken literally. Although it could be. There are a lot of literally invisible things in this book. It motivates someone to dig deeper, to join in, jump in and take the baton. This is how I think about making things—it’s just meant to motivate more action, to get involved, to start a conversation. Otherwise you’re just a preacher, and that’s boring.

Guernica: Well, a lot of people went to see the Pope.

Tavares Strachan: True, true. They sell a good story; pretty damn good story. I mean, what are you going to say?

Guernica: What’s the closest we’ve come in pop culture to that level of storytelling?

Tavares Strachan: Oh my God, fuck. Other than other religions?

Guernica: Anything that’s kind of glanced off of it, approached it?

Tavares Strachan: That’s a good question, man. Maybe the internet, as a phenomenon. Because you go to it. Me and you have an argument over a sports stat, and I’m like, no, fuck you, it was this, and you’re like, no it was that, let’s go confirm that.

Guernica: There used to be a great blog years ago called “Bad Questions for Yahoo! Answers,” that thing where you can ask questions and whoever comes across it can answer. People would go to it with very strange questions, moral questions, ethical questions. They’d appeal to authority there, like, Is it okay if I cheat on my significant other if these are the reasons why I want to? Which maybe speaks to that on some level. When I was a kid the internet wasn’t the ubiquitous thing it is now. No sense of the definitive answer being out there like this.

Tavares Strachan: The mighty Google.

Guernica: The great pivot point in contemporary history, when Google switches from noun to verb.

Tavares Strachan: I know, I know. The internet, religion—very similar.

This is how I think about making things—it’s just meant to motivate more action, to get involved, to start a conversation.

Guernica: Important, for sure, but do you think it’s a good thing?

Tavares Strachan: I will say that it’s the only thing that can counteract colonialism, and all the holdovers from colonialism. It puts power in the hands of people who would never have that power, and however minimal that power is, it’s still something. Most of the work I do, I do it because I can find it, easily, and research it. What would it be if it was much harder for me to do that?

I think a part of religion, and the history of religion, especially Judeo-Christian stuff, is all about denying access to information. It’s about centralizing knowledge. So once you break that down, and knowledge is decentralized, what are you going to do? That’s why people spoke Latin, right? It really was a kind of underground currency for a particular group. So is it a good thing? I think it counteracts the post-colonial condition, but I think it still comes down to ideas. It comes down to people with really fucking good ideas, and working hard to make those good ideas happen.

Guernica: It emphasizes, I guess, invisibility as a two-way street. Not only are marginalized people invisible, but also so much was kept invisible to them. And that’s no longer the case as much.

Tavares Strachan: Exactly. You can be in the most remote… I had a conversation with a friend of mine about the idea of solitude. If wilderness is even possible. Can you be in the middle of nowhere now? Where is that? I think that’s a really interesting collision with the idea of Google.

Guernica: A guy like Christopher McCandless, who goes to escape everything, and now there’s a book and a movie about him.

Tavares Strachan: Exactly, exactly. So how do you have wilderness and solitude in the age of Google and the internet? Is that possible? Fucking GPS tracking. How are you going to be in the middle of nowhere? I want to know.

Guernica: Is that something you’re interested in exploring in your work at some point? Technology and surveillance?

Tavares Strachan: I’ve thought about it, but all the results ended up ignoring something that was more cerebral about art making, and just became really lopsided. They weren’t a good dish, where it was well composed. The mythology of the big bad wolf, technology as the big bad wolf, is pretty present in our condition, and I think there are reasons to be afraid of it, for sure, but I also think it’s hard to make a beautiful symphony without the right cello, and that cello is a condition of technology. We’re conditions of technology. We’re the species that have the thumbs and the large brains and we want to cut things with knives and we want to make bows and arrows and this is the evolution, or devolution, of all those ideas.

So it’s hard to say. Are we devolving or evolving? Are we becoming more civilized or less? There are all the things that keep me up at night. Why are there poor people in New York City? Not even poor–there will always be poor people–hungry people is what I mean. It’s mind-boggling to me. It’s so interesting to me to always see how we’ve found ways to break it and fix it and break it again. And not understand at all the cycle of it, of any of it.

Guernica: That idea, break it, fix it, break it again, seems very present in your work. In a literal sense, even.

Tavares Strachan: Yeah, that’s very true, now that you say it.

Guernica: In the Franklin show, like we talked about earlier, that’s in one sense a person broken down into constituent parts. Maybe to some degree the breaking is the fixing?

Tavares Strachan: Or maybe it’s already broken, and I’m just representing broken. There will also be a time when these narratives aren’t invisible. When more people will care about them. What happens then? This is where the poetry component of storytelling is interesting, in that authenticity is not the highest thing on the agenda. Especially when you’re an artist. It’s not as important.

Tavares Strachan’s Seeing is Forgetting the Thing that You Saw is on view at Anthony Meier Fine Arts in San Francisco through this Friday, December 11th.