“Dear Ms. Summerfield—We regret to inform you that your husband does not love you anymore. Your marriage is over, effective immediately.”

There was more—a lot more—but it was too much to take in all at once so I called Amber instead.

“Are you sure?” she said, chewing something on the other end of the phone.

I read over the paragraph again. “That’s what it says.”

“What else does it say?” It sounded like almonds or something, some kind of nut.

“I don’t know. A lot.” I flipped through the pages. There were hundreds of them, it seemed, and it wasn’t just words either, but drawings and diagrams too.

“Well, you have to go get him,” she said definitively. I heard her dusting off her hands.

“Now?”

“Yes, now! Of course, now! Go, go!” She yelled like a coach then hung up.

So I went. I grabbed my keys and ran out to the car. I was still in my pajamas—yoga pants and a floppy sweatshirt from a thrift store—but Amber had yelled to “Go! Now!” so I did. As I backed out of the driveway, I noticed some of his stuff in the yard, a trail of things that started at our side door then kind of wended away, as if trying to decide which direction or whether to go. I knew it was his stuff because all the errant socks had holes in them (I could tell even from the car) and there was random shit like old keychains and bottles of carpenter’s glue. The trail turned onto Woodstock then went up 82nd for a while, eventually going onto the freeway—surfboard wax and chisels and books on history and ecology and some pens and a couple of shoes. I followed the trail for a good forty-five minutes—which felt like a lifetime—but after a while it started to trickle and peter out, then it dried up completely. There was nowhere else to go so I just went home.

When I got there, the cat was slumped against the book—bound like you might get done at Kinko’s—sort of patiently and steadily cleaning herself, licking her chin and paws.

“Everything, eventually, must come to an end,” the preface said. “Painful as it is to admit and to know, lakes dry and cliffs erode and love, too, changes and slips away. You should be thankful for the time that you shared. Be grateful for the memories and, if bitterness arises, let it go.”

But bitterness did arise, quickly. I took a shower and ate a piece of toast and looked around and blinked real slow, then said, “What the fuck?” I stood as if he were right there in the room. “You can’t just fucking end it. We made a promise. You can’t just leave.”

I glanced down. “Yes, he can,” the preface said, “is the answer to a statement like ‘You can’t just fucking end it’ or ‘You can’t just leave.’ It may take some time to accept, but he can—and did—just leave.”

“Of course, you’re angry,” Amber said when I called her again. This time I heard what sounded like a chip bag, the crunching of chips. She’s always going somewhere, working or picking up her kid or taking care of shit, so she eats in the car. “I’d be fucking pissed.” Amber is the kind of person who is exceedingly good at validation. She’s a trained therapist and an incredible friend, which is why I told her first. It’d already been like two days and I hadn’t told anyone else.

“What are you gonna do?” she said. “What would you like to do?”

“Murder him.”

“Zu,” she said, like that’s not funny, and it wasn’t. We knew people who’d been murdered; we weren’t allowed to make that joke.

“What do you want to do?” she said again. “Do you want to call him?”

“I can’t. He doesn’t have a phone.”

“Still?” The crinkling stopped. “God dammit. Are you fucking kidding me?”

It was sort of the chief thing with him and her and with lots of people, our family and friends. He really didn’t want to have a phone (they were too expensive, all people did was stare at them all day) and everyone took offense to this, because it was impossible to get a hold of him and also, his choice felt like a critique, like he thought he was better than us or something, more evolved. How many calls did I intercept on his behalf? How many nights were there when he was out of town and I didn’t hear from him, sure that he was dead, killed somehow doing fieldwork in Peru or mangled in a car crash on some deserted road? A whole chapter could be written just about this.

“Can you send him an email?” she said, eating chips again.

“I guess so.” But I didn’t want to send him an email. It felt pointless and pathetic. Like, what would I say? Hey, it seems pretty obvious you’re gone for good, but could you just confirm to let me know? Also, it’s not like he would write back. He was crappy about emails too.

The book was called Ending One Life and Starting a New One, which seemed like a pretty condescending title (“Fuck you. I’ll never start a new life.”)—but I settled in to read it anyway. It was massive, which made sense because we’d been married for eleven years, and together for seventeen. It didn’t have an author, or anyway it wasn’t attributed to anyone, and a quick flip-through showed it was extensive, like a novel draft or a PhD dissertation on the Peruvian Amazon. I’m a slow reader and thought, vaguely, This will take me forever. The cat came and settled on my lap.

“Introduction: A Marriage’s End~

Tracing a marriage’s end is a monumental and perhaps impossible task, but one worth pursuing, particularly if you are interested in starting a new life. It is important to tease things apart, to interrogate aspects of yourself and your relationship, to seek and explore nuance the way you might hold a prism to light. Among other tasks, you will:

-Review what happened and where things went wrong

-Spend some time in memories, both good and bad

-Practice skills such as empathy, emotional development, mindfulness, and reflection

-Ask yourself some tough questions, such as: What patterns and behaviors were damaging? What particular dynamics of your relationship would you like to leave behind?

Like a life well-lived, this text is meant to be interactive and hands-on. Take your time and go slow. You may be tempted throughout the course of your work to look at the answers in the back. Please note: there are no answers in the back.”

Chapter One laid it all out. We met on an airplane, of all places, parked on the tarmac at Los Angeles International. We were both students at California State Universities, embarking on a year-long study abroad trip to Spain. He was enrolled at Humboldt State and I was a student at Cal State San Bernardino, and since the state universities are linked, their study abroad programs align. Which is to say that, though meeting on an airplane sounds exceedingly romantic, fate-wise being on the same flight was not that big a deal.

The next part, though, is exceedingly romantic, or anyway, over the following months we fell in love. He was funny and sweet and unlike any boy I’d met before. He lived in Madrid and I lived in Granada, and we’d travel back and forth to see one another. We went to museums and took long walks and cooked meals and smoked on his balcony and rode trains, and he didn’t try to have sex with me or even kiss me though when we visited we always slept in the same bed. We’d twine our bodies around one another and just sleep and sleep. He brought me fresh coffee every morning, wafting the smell and gently singing “Rise and at ‘em! Up and shine! Drink your coffee, it’s gonna get co-old!”

At the end of the year, we went back to our separate ends of California and found that we could not live apart, so I moved to Humboldt and got a job at a car dealership while he went to school, then we moved to San Diego and both worked crappy jobs. We traveled, we fought, we camped, we broke up for a time then came back together, we lived here and we lived there and then it was a few years and we decided to get married and then it was more years and then it was even more and then all of a sudden it was seventeen years (“Which is a really long time,” the book pointed out) and our lives had become as entangled and entwined as two ropes, tied into not one or two but seemingly infinite knots, so many habits and behaviors and intimacies and inside jokes that it would’ve been impossible to separate out all the individual strands, but now “Here you are,” the book said, and showed me an elaborate drawing of those two ropes—only it looked less like knotted ropes and more like a tangled ball of yarn, maybe, or like an abandoned rat’s nest.

I finally decided to call my mom. She’d left at least three messages and I’d ignored each one. It’d been five days since he left (maybe more?) and if I didn’t call her she would freak, the same way I would freak when he didn’t call me. That kind of pointless panic runs in our genes.

“Renee?” she said frantically when she picked up. My family are the only ones who call me that anymore, and him too. Everyone else calls me Zulie or Zulie Bear or ZuZu or just Zu. I hardly ever hear plain Zulema anymore. “Where have you been?”

“I’m here,” I said. “Sorry.”

“What’s wrong?” She can read anything and everything in my voice because she’s my mom.

How much should I say? That we’d been fighting lately? Lately as in, like, the last few years?

“He’s gone,” I finally said, and sank into the couch.

“Gone? Like working again?”

“No, like gone. He left.” I said it numbly, a big block of ice where my brain had once been.

A long silence filled the phone. My mother is a kind, wise woman. She works as a hospice nurse and volunteers in her spare time. She keeps a garden where—no joke—neighborhood squirrels come and eat from her hand. Still: she is a person and sometimes people say stupid shit.

“Well, I’m not surprised,” she said.

“Mom,” I said.

“What? I’m not. He’s been unhappy for years.”

“It’s still a rude thing to say.” The ice had started to melt and now my eyes were wet with tears.

“You’re right,” she said, then after a pause, “I’m sorry.”

I didn’t say anything because sometimes people are assholes even if they don’t mean to be and I felt like my mom was kind of being an asshole, but there was a lot going on and I didn’t know what to make of it so I just sat there, crying a little and holding the phone. It occurred to me then that everyone around me had suspected it would happen, they’d been expecting it for a long time, but no one had said anything or even dropped any hints and I was the last one to know, like when your fly’s been down or you have a booger in your nose, except your fly’s been down or you’ve had a booger in your nose almost your whole life, your whole adult life anyway, and all the people around you have been like “Ugh, poor thing” and you’ve just been plugging along, hoping for the best, without a clue in the world, really just no idea.

“Can I send you a Trader Joe’s card?” my mom said after a minute. “Let me send you a Trader Joe’s card.”

“Okay,” I sniffed, because who would say no to a Trader Joe’s card.

Chapter Two began: “By now, it’s likely beginning to sink in that things have changed. It’s been a few days and you’re starting to notice the shift.” Which was true; for one thing, he wasn’t around to bring me coffee in the morning and I couldn’t figure out how to make the machine work. The house was notably more quiet—none of his music, his loud footsteps like fee fi fo fum, the sound of him coughing or snorgling or clearing his throat. No candy wrappers by the bed. No little beard hairs in the sink.

I decided to clean up. Fuck it. If he wasn’t coming back then I was going to make the house the way I’d always wanted it—no more looking at his ugly-ass things. I put The Beach Boys on, loud, because I was never allowed to listen to them when he was here; they weren’t authentic surf culture or something stupid like that. You’d have to ask him; except he was gone so you couldn’t ask him, so I blasted that shit while I cleaned. First, I had to assess what all he’d left behind—because of course he’d left a bunch of crap behind. I started to make a pile: file folders and his reading light and his pipe collection and his disgusting gardening shoes. He’d taken most of his clothes, obviously, but I saw that he’d left all of his coats behind, and I thought, Oh! He’s back in Peru because I was pretty sure you don’t need a coat in Peru. For a brief instant I filed that information away, like tucking a note into my pocket, a little tidbit for later in case I decided to track him down—I still hadn’t decided yet—but then I realized it wasn’t every coat just the coats that were too small, the coats I’d been saying to get rid of for years, the coats he hadn’t worn since Dubya was in office, the coats with holes, the coats with tears, because of course he’d left them behind, along with all the other shit he didn’t want to deal with anymore (including, I guess, me?) and I said, not under my breath even but totally out loud, as if he were right there in the room “You son of a bitch” and had zero—but zero—interest in tracking him down.

“Things You Will Not Miss” the book said, and I wrote “I will not miss picking up all his loose ends and I sure as hell won’t miss him being late all the time.” I wrote a few more (“Smoke on the Water,” his dumb air-horn joke) then I saw that down in the corner there was a little box labeled “Things You Will” and I wrote ABSOLUTELY NOTHING AT ALL.

The next few days were incredible. I drank smoothies and went to the gym—for like, twenty minutes, but still: I did the elliptical and sang “To the left! To the left!” and some dude kept looking at me—he’d like do a rep and then look up, stare a little, look away, furtively, and I looked back. I mean, I stared back, like “C’mon bub. Just try it. Try and talk to me.” When it turned out he wasn’t looking at me but at the person behind me (I guess they went to college together or something), I thought “Good. I don’t need a man.” I came home and stood naked in front of the mirror and turned this way and that, grabbing my own butt and hoisting up my little boobs and saying, as if my husband were in the room, “You idiot. You don’t even know what you’re missing”—even though, yeah, he probably did, he’d been missing it on and off for seventeen years. I went to the mall and bought new clothes (divorce clothes, I called them) and started wearing make-up and heels, just like little booted heels but still: I looked good. I could be and do anything I wanted because he was gone and I was finally free.

The book said “Let’s talk about your new-found liberation” and I wrote “Fuck men” and the book said “Elaborate please” so I wrote “My whole life I’ve been shaping myself around boys and men” and then the book said “Show your work” so I did.

The first boy I ever loved was named Danny; I was so young, first grade. He was golden-skinned and had wavy brown hair and a constellation of freckles running across his cheeks and nose, and the fact that every girl loved him, that every girl was as obsessed as I was, only made me want him more. What’s Danny doing? Where’s Danny sitting? I became attuned to his movements and whereabouts the way a bat knows the contours of the dark. When Danny said “The New Kids are dumb,” I went home and threw all of my posters in the trash. He liked Paula Abdul so I liked Paula Abdul, we all did, and when he started listening to Bon Jovi everyone else did too. I knew, on a cellular level, that I’d never have him, knew that he would never love me back, and everyone knows that kind of love is dangerous. It grows in you like a fungus, and then what is it? It’s not really love anymore.

Danny was just the start, the beginning of a lifetime of want and need, one long ribbon of desire perpetually unspooling from the center of my chest. After Danny came Greg, and after Greg came Mike, then Ricky, then Joe—a parade of boys I tried to attract and appease. When Jared said he liked girls in jeans, my wardrobe was decided for the better part of a year. Later, Matt Hunter read the French existentialists so I read the French existentialists too. And so on. When Tommy Jimenez said I would look better with short hair, that was it: I went home and chopped it all off.

And now I’m like a puppy, I’m fucking trained: What do you want? How can I take care of you? What do you need?

“Fuck that noise,” I wrote, and played Pet Sounds again, and then again, and again.

The book, of course, weighed a freaking ton. I couldn’t reasonably travel with it or carry it around, so mostly I read it on the couch, propped open on my lap. It was filled with details and information: maps of all the places we’d been (sometimes with little sidebars showing fights we’d had or spots where we’d made love), our own maps that we drew for fun, pie charts, graphs, captioned photos, scans of our marriage certificate and fingerprints, the titles of our cars, print-outs of emails, transcripts of fights (I flagged those to return to later; I’d always wished I’d had them), cards and drawings and doodles and notes, “Dear Toad, I’m glad you are my best friend. Love, Frog”—that last taking the breath out of me a little, which I did not expect.

“What did you expect?” Amber asked when she called, not in a mean or sarcastic way, just a gently probing one.

“I don’t know. I liked last week better.” I was in sweats again, hadn’t left the house in days.

“What was last week?”

I paused, looking around the room. He used to leave his shoes right there, and his coat hung on that chair. “I didn’t care that he was gone.”

She was quiet, then said softly, “And this week you do.”

“Yeah,” I said, and the yeah caught and clung in my throat.

We were quiet for a long time. I could hear seagulls behind her and wished that we were together, walking on the beach. “You want me to fly up?” she finally said, and I said “No, it’s okay,” because I knew she was broke. She was broke, I was broke, the whole fucking world was stupid and dumb and broke.

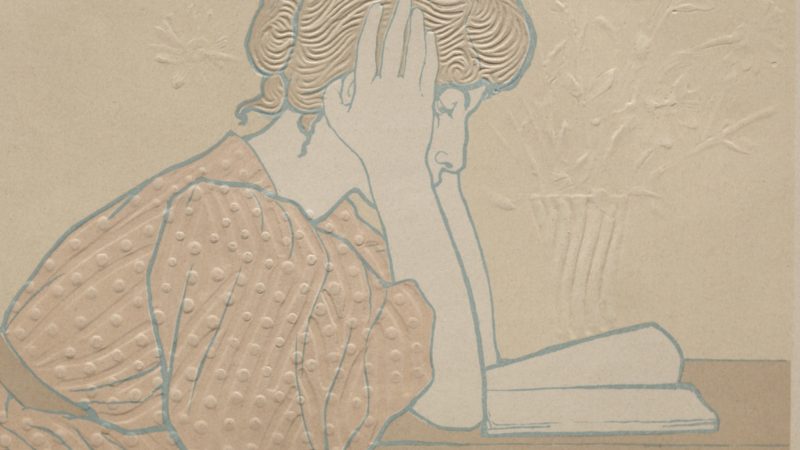

The next morning, the book seemed heavier than it did before. I could barely pick it up, as if overnight the muscles in my arms had atrophied or someone had filled the book with lead, or both, maybe both, because I had to drag it across the floor and heave it onto my lap. The house was cold and gray, even though it might have been spring.

After the lists and the transcripts and the maps, the book took a turn. Now, there were hardly any words at all. The pages were black and squidgy with ink, oily and runny like slime. Many of them stuck together in large, stubborn clumps.

Leaning in close, I could make out a handful of occasional words: “the house in St. Johns,” “Elvis song,” “mud fight in the rain.” We were only twenty then, maybe twenty-one. He lived up in Trinidad and we were on a walk by the river and he said something annoying, I don’t remember what, and I threw a little bit of mud at him, and he threw a little bit of mud at me, and then I threw more and then he threw more, and then that was it, it was all-out war, and we were laughing and screaming and chasing each other down the beach, ducking behind boulders and trees, lobbing fistfuls of wet silt and sand, and I had mud in my hair and mud in my teeth and he couldn’t stop laughing, god, how sweet it was when he really got into it, when he really let loose and just laughed and laughed.

It went on—this inky black sludge went on for pages, days, weeks. I began to lose track of time. I started wearing leggings and an oversized down vest someone had given me, and I hardly ate, and I stopped combing or washing my hair, and I didn’t leave the house and when I did it was only to Trader Joe’s, where I filled my cart with frozen pizza and cookies and lots and lots of beer. “You havin’ a party?” the check-out guy said, and I said “What the fuck, a party?” but I said it with my eyes. I lived off of credit cards and lied in texts to my Mom: Feeling great! Doing fine! I stopped answering Amber’s calls because I couldn’t talk anymore, and I could not bear to go in the bedroom so instead slept every night on the couch with the cat. In other words, in all but the most basic ways, I stopped being alive.

Finally, Amber texted. “Why aren’t you calling me?” I knew I couldn’t avoid her anymore.

“Zulema?!” I could hear the wind whipping through the open window of her car.

“Hey,” I said.

“Where are you? Are you at home?” She had that tone I would get when I finally did hear from him, that tone you use when you love someone so much it makes you mad.

“Yeah,” I said, and I could feel her soften then, even though we were on the phone, knew that she knew I hadn’t done anything reckless or crazy, that I was just really sad.

“Are you still reading the book?” she asked.

“Yes.” I tried to say more but could only manage one-word answers, it seemed.

“What’s it saying now?” she said gently.

“Memories,” I said, and blinked slow, because I hadn’t talked in weeks. “It’s memories now.”

“Good or bad?”

“Good,” I said, except they felt bad now. Or not bad but rotten, limp, sad, because they were gone. My hands were spotted with ink.

We were quiet for a long time. Thing is, Amber was close to him too. She officiated our wedding, for criminy’s sake—we were practically family. And since a family is something you build like a house, with him gone it was like a wrecking ball had taken out an entire floor.

“I don’t understand,” I finally said.

“You don’t understand what, love?”

“How could he just end our marriage like that.”

“Like what?”

“Like just be done and that’s it. It’s so fucked up.”

“I mean, Zu. That’s not entirely what happened.”

“What do you mean?” But I said it more like what the fuck.

“You know that’s not true. You guys had already decided you’d split by the time he actually left. You both knew it was over.” She was totally right, and it ticked me off.

“Well, yeah, but he’s the one who didn’t want to be married anymore. I never wanted it to end.”

“Eventually you did.”

“What’s your point?”

“My point,” she said, and I could tell she was getting pissed, “is that you can and should feel heartbroken, but you can’t just make shit up.”

“What the fuck? Why are you always taking his side?”

And then a gate opened, and she wasn’t a trained therapist anymore or my best friend, but someone who was angry and rightfully so because I was being a jerk.

“You know what, Zulema? I’m sorry you’re hurting—I really am. But this is totally inappropriate. You’re being untruthful and manipulating circumstances, and frankly, I’ve got enough shit on my own plate to be treated like this by you.”

“Dude,” I said, still all racked and stacked with defense.

“I don’t think I want to be on the phone anymore,” she said abruptly.

“Fine,” I said.

“Fine,” she said back, then hung up.

“Fuck you!” I yelled, not so much at her but at all of it, at the whole fucking thing.

“She’s kind of right, you know,” the book said when I glanced down. The memories had ended, or anyway there was a break and now it was a section called “The Showdown.”

“What are you talking about?”

“She’s right about the manipulation. You’re entitled to your feelings but you’re not entitled to the facts.”

“What are you, Twitter?”

“Sarcasm will not serve you at this time.”

“Oh, okay great. Do tell, what will serve me?”

“Honesty.”

“You want honesty? I’ll be fucking honest. I’m pissed. We made a god-damn commitment and he just decided Uhp, that’s it! I don’t want to do it anymore.”

“Again, that’s not the whole truth.”

“Then tell me, oh wise fucking tome, what is the whole truth?”

“For one thing, you have yet to acknowledge your role.”

“My role? What the fuck do you mean, my role?”

And then a new section began called “Things You Might Have Changed.”

“One,” I wrote, so angry I could hardly steady my hand, “I would’ve asked him to go to therapy. He needed help.”

“We’re talking about you here,” the book said, as if it knew what I was going to write. “What things could you have changed?”

“I was a really good wife!”

“Of course you were. You were an excellent wife. Still: what could you have changed?”

“He always wanted to get up early and I wanted to sleep late. Maybe that’s what did us in.”

“That’s doubtful. Try a little harder.”

“I don’t know. Hugged him more?”

“Okay, that’s good. What else?”

“Nagged him less, maybe.”

“Okay—”

“But that’s the thing,” I interrupted. “A woman asks a man for help and all of a sudden that’s nagging?” My vision was getting blurry and my head was starting to spin. “We’re adults, god dammit! Everyone can pull their weight.” And then I blinked because the rage was coming in, through the windows and around the cracks in the door. “THAT’S NOT EVEN THE POINT! The point is he left and YOU CAN’T JUST FUCKING DO THAT!” Now he was here too, right here in the room, and I would never get rid of him but also he was wholly and entirely gone. “You know what then, asshole? Just go! Fucking go!” And then the rage was everywhere, it was all of me, and I screamed like a cavewoman and picked up the book and hurled it as far as it would go. Its pages made a sound like a thousand birds and the cat—the poor cat—ran terrified into the other room. I slumped against the wall and pounded my fists into my thighs.

But the book weighed so damn much it hardly flew anywhere at all, and lay splayed open just a few feet away. It’d fallen open on a page called, simply, “The Wound.” I was making my way towards his apartment in Madrid, but kept confusing the stations and was terribly lost. The night before, I’d been running, drunk, through the streets of Barcelona, me and some friends just fucking around, but I’d tripped at one point and it was a nasty fall—I bruised myself up pretty good and ripped my jeans, gashing open the skin on my knee. I was so drunk I hadn’t done anything about it, fell asleep in my clothes and in the morning somehow got to the train, but was now exiting station after station all over the endless suburbs of Madrid. At one point, there was a rainbow, and that was nice—I was so young that none of the other stuff mattered. When I finally did find his place (after hours of walking around in the rain), he opened the door and took one look at me, in my sopping and torn clothes, and led me to the bathroom, where he found a first aid kit and dressed my wound. He didn’t admonish me or ask questions (How much did you drink? Why didn’t you clean this last night?) but instead tweezered out all the bits of gravel and disinfected the cut and, for good measure, snapped the arm off an aloe plant and smeared the wound with its gel. It was then, sitting on the edge of the bathtub in his apartment in Madrid, that I knew I loved him and that there was no turning back.

Softness had replaced the rage, and a new section began and though I hated him I still loved him, a lot, so I blinked and ran my fingers over my eyes. It was called “What He Would Say.”

“I loved her,” he wrote, his sudden hand-writing like a punch to the throat. “Of course I loved her. I still love her. She’s funny and she’s smart and she’s incredibly caring—just really, really caring.” I could barely read it, my eyes were so full of tears. “But I just couldn’t do it anymore. It’s like she refused to see me, or didn’t know how, and I just couldn’t live like that anymore.”

And then a quiz: “Is that true? Did you refuse to see him?”

“Of course not,” I wrote, swiping at my face. “All I did was see him. My whole fucking life was about seeing him.”

“How? In what ways?”

“What do you mean?”

“In what ways did you see him? Be specific.”

“Jesus, are you for real? Okay, one, I was always sending him jobs I knew he’d like, and I’d help with goal plans and problem-solving—”

“Those are all nice things, but they’re things you did for him. Doing is not the same as seeing.”

“I don’t get it,” I wrote, because I didn’t. I was crying now—really, really crying.

“You don’t now, and that’s okay. But you will. Someday you will.”

It went on—the book went on and on and on. It started with a paragraph called “Making Amends,” in which I called Amber in the morning and apologized for being a turd. There was a long, slow, steady march of days where all I could manage was to force myself out of bed like commanding a marionette, months of just trying to figure out what to do. I flipped through the book and saw so much, and yet they were just glimpses of all I had yet to read: leases from rental houses where mine was the only name, photos of me camping alone, a detailed drawing of the loneliness I’d carry, like a charcoal fist nestled in my gut. There was a warning that my first Christmas without him would be the shittiest week of my life, and showed me curled like a fetus on the guest bed at my mom’s, sobbing into a pillow while she sat next to me, a hand on my back and her face twisted with sorrow and concern. There were boxed reminders that said “No mud, no lotus” and “This too shall pass,” and at one point a flipbook in the bottom right of some of the pages, showing a charred hunk of coal slowly transforming into something else, though I couldn’t quite tell what it was—and more, pages and pages and pages more. God damn, I thought, how long is this thing, and felt a pit in my stomach because I would never get over this, it seemed—I’d be reading this giant incredible stupid book for the rest of my life, invariably devastated and enraged.

But then I couldn’t help it: I turned to the very end to read the last line, which as a gesture he would’ve hated. (“You’re so impatient,” he’d say, and I’d say “Impatient and curious are two different things.”) I was shocked because, sitting there hungover and unshowered on the living room floor, the last line was impossible to believe. It said, simply, “You’re going to be okay” and then, as if it knew I was skeptical to my very core, the book repeated itself: “You’re going to be just fine.”