Where the river pooled up for the boys

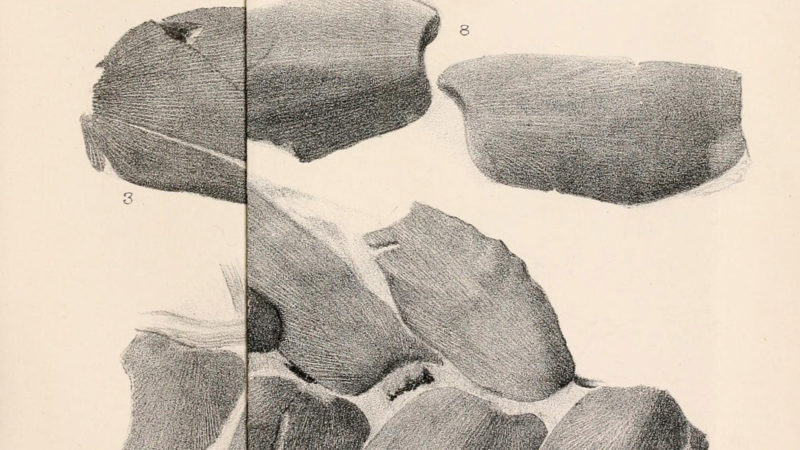

a stone emerged.

You didn’t see it any other way:

just a stone, big and anodyne.

When we rose up from the murky water

we’d scale it like lizards. And then

a weird thing happened:

the dry mud on our skin

drew our bodies closer to the landscape:

the landscape was the mud.

At that moment

the stone wasn’t hard or impermeable:

it was the back of a great mother

lying in wait for shrimp in the river. Ah, poet

yet again the temptation

of a useless metaphor. The stone

was stone

and that was enough. There was no mother. And I know now

it assumes responsibility: to watch over us

in its impenetrable intimacy.

My mother, however, has died

and she is neglected by us.