For Brazilian-born artist and modern-day trickster Vik Muniz, subverting his own images is all part of the game.

Vik Muniz is trying to write a sentence.

Appropriately enough for Muniz, a Brazilian-born visual and conceptual artist, this sentence is made of pictures rather than words. It takes the form of a rebus, a puzzle composed of images and symbols that suggest meaning, the kind of playful art trick for which Muniz has become famous. In one corner of his Brooklyn studio, above a box of colorful plastic toys that he’s using in another project, he has taped several long rows of 3×5 prints on the wall. In one section, Vija Celmins’s To Fix the Image in Memory—eleven pairs of stones with their replicas in painted bronze—appears next to a model of steel tailor shears from 1900, which is juxtaposed with Martin Creed’s Work No. 301: A sheet of paper crumpled into a ball.

Appropriately enough for Muniz, a Brazilian-born visual and conceptual artist, this sentence is made of pictures rather than words. It takes the form of a rebus, a puzzle composed of images and symbols that suggest meaning, the kind of playful art trick for which Muniz has become famous. In one corner of his Brooklyn studio, above a box of colorful plastic toys that he’s using in another project, he has taped several long rows of 3×5 prints on the wall. In one section, Vija Celmins’s To Fix the Image in Memory—eleven pairs of stones with their replicas in painted bronze—appears next to a model of steel tailor shears from 1900, which is juxtaposed with Martin Creed’s Work No. 301: A sheet of paper crumpled into a ball.

“Rock, scissors, paper,” Muniz says with a grin as he points to these images.

The picture pairings don’t yield literal words or phrases in the way that a true rebus would, but each of the images on the wall is connected to the next, mostly in obvious, funny, and visceral ways. You don’t have to be an art history expert—or even to know anything about art—to see how they relate. The narrative that develops almost resists depth, allowing you to skate along the surface, looking for simple visual clues, identifying overlaps between neighboring images in their most basic elements: form, color, subject.

The prints—there are eighty of them in all—are copies of work in the permanent collection of New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, and they are assembled here as a trial run for Rebus, the Artist’s Choice exhibit Muniz is curating for MoMA. “It’s about group shows, how the experience of images is cumulative,” Muniz tells me earlier that day as we sit talking in the office adjoining his studio. As you move through the exhibit, which follows a one-way route, the individual pieces should disappear behind the broader rhythm of the sentence. “It’s like a ride. It’s very dense. It’s very packed,” he says. “You start becoming conscious that the show is not about the works themselves, it’s about the spaces between, and the lingering, thinking, that comes from when you see one picture and then the next.” In other words, it’s not about what you are seeing; it’s about what’s going on inside your head.

The MoMA show is a perfect mirror for the paradox at the center of Muniz’s own art: he encourages a shallow surface reading while simultaneously trying to subvert it. John Cage once said that “the highest duty of the artist is to hide beauty,” but Muniz seems to have turned this maxim on its head: he uses the seduction of his images to sneak in tricky concepts.

One of Muniz’s most iconic works might be Double Mona Lisa (Peanut Butter + Jelly) from his “After Warhol” series of 1999. The work is literally a sandwich of images and ideas. There are so many delicious layers here: it is a photograph of two paintings—side by side Mona Lisas, one created from peanut butter and the other from jelly—that are themselves copies of Warhol copies of an iconic work of art. Looking at them, you instantly search for the familiar half smile and glancing eyes, and are rewarded with recognition, but it’s hard not to notice how the two Mona Lisas are different—you wonder which is more “faithful” to the original. Take a closer look and you get lost in the materials. The work induces an almost Pavlovian response: you want to swipe your finger through these sandwich spreads and stick it in your mouth. The peanut butter version seems to have been “painted” with a kitchen knife: The layers are creamy and rich, and light glances off of the smooth surface. And you can see the lumps of fruit and the seeds in the jelly, which create the illusion of depth.

Looking at this photograph, you could simply admire the visual texture, the technical mastery required to wrestle jelly into service as paint, the sheer ridiculousness of seeing something hallowed so debased. Or you might begin to think about how images and our visual memories work: they lie to us, but we want to believe what we see, and a copy of a copy somehow makes the original fresh. Or you could, as the artist hopes, get caught somewhere between the first reaction and the second, in which case you’ll enter a liminal mental space, the evocation of which is perhaps Muniz’s true art.

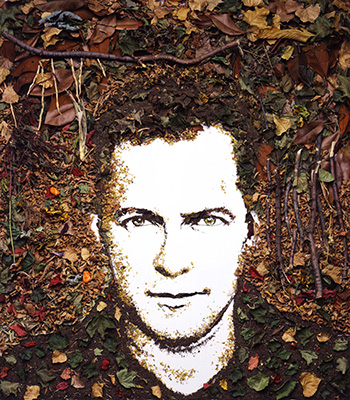

When I visit Muniz in his studio, it’s a rainy afternoon in early November—the day after Barack Obama was elected President of the United States, when Brooklyn erupted into one giant street party. Despite confessing to a hangover, he is talkative and relaxed. He speaks with a slight Brazilian lilt—certain syllables get unusual emphasis. Still boyish at forty-seven, he has a round, pale face; big, dark eyes; and closely shorn black hair. He’s casually dressed in black jeans and a black t-shirt. The beginnings of a grin play around the corners of his mouth as though he is about to tell me a joke. Maybe he is. Maybe it is all a big cosmic joke to him—how he came to be an art superstar by playing with images and ideas.

The MoMA show is a perfect mirror for the paradox at the center of Muniz’s own art: he encourages a shallow surface reading while simultaneously trying to subvert it.

In fact, Muniz laughs a lot—about his love of magic tricks, about the fact that the medium of photography was used to tell “lies” from the very start, about the book on how to get great abs on his desk. “I think if I just read about it, buy the book, I can get good abs,” he says with a giggle, poking fun at himself. Alternatively animated and pensive, professorial and self-deprecating, he seems to enjoy playing in person the part he has assigned to himself in his work: he’s the archetypal trickster, the boundary crosser, inhabiting the intervals between low and high, visual and conceptual, medium and message, art history and pop art, and even, more broadly speaking, between the sacred and the profane.

This leads us to wonder: how has someone so intent on crossing boundaries managed to become such a firmly established—and bankable—figure in the art scene, and what does that mean for his work? The answer to both questions lies, perhaps, in the very trickery that produces his art in the first place. As Lewis Hyde, art theorist and author of Trickster Makes This World: How Disruptive Imagination Creates Culture, says, the true trickster doesn’t just inhabit boundaries, he creates them. He “brings to the surface a distinction previously hidden from sight.” Creation depends on this vision, and as such, cultural tricksters create value. According to Hyde, the “origins, liveliness, and durability of cultures require that there be space for figures whose function is to uncover and disrupt the very things that cultures are based on.”

Muniz, who has been on the New York art scene for some twenty years now, is best known for conjuring reproductions. As the Double Mona Lisa (Peanut Butter + Jelly) image suggests, he recreates iconic or contemporary works of art out of unusual materials and then photographs the results. Along the way, he has remade landscape drawings by Corot and Claude Lorrain in scads of thread; drawn photographs of children of sugarcane workers in sugar; and painted portraits, still lifes, and news photographs with color pantones and ink grids. These photographs, which now hang in museums all over the world, are often very large and borrow from different cultural touch points, but this is more than just appropriation: it’s a kind of trompe-l’oeil, a trick of the eye, and some of the stuff he paints with—food, dirt, garbage—is loaded with its own cultural weight. His pictures violate our notions of where these materials belong: not on a plate in the kitchen, or in the dump, but now in the rarefied world of the gallery. Low materials in high places.

“My art is about the conflict between mind and matter,” Muniz tells me. “It’s about seeing the material and the image and the way they don’t connect. It’s like watching a bad actor perform a classic character. You see the actor, and you see the character, but you cannot see both at the same time. You see the split. And in the split lies the magic of representation, which is exactly the moment when something transcends itself.”

These ideas about transcendence, though, come wrapped in accessible, fun, and at times, even slapstick packaging. In one series in 2001, he had skywriters draw cartoonish clouds in the sky over New York City, among other places, and then photographed the results. In another, he painted Sigmund Freud in chocolate syrup, a play on Freud’s investigations into the psychology of pleasure and desire. In a sense, he lampoons the painful self-seriousness of so much conceptual art. There is a democracy in his approach: he wants everyone to get it—old, young, art-savvy, and naïve.

And people do seem to get it: Muniz is wildly popular with museum-goers, drawing huge crowds to his shows, and his work is in the collections of major art museums around the world. Even in this dry art market, Meg Malloy, a partner at his gallery Sikkema & Jenkins, tells me that many international museums are in the process of acquiring additional Muniz pieces, suggesting that his work is recession-proof. He’s now one of the masters, a perennial art star for the ages. His shows generally get enthusiastic reviews, even if some reviewers can hardly suppress a giggle. He is also widely loved by his contemporaries, evidenced by the fact that so many of them—including Cindy Sherman, Chuck Close, John Baldessari, and Gerhard Richter—have let him reproduce their work. (He credits them in the titles of each piece.) There are even some younger artists these days following in his footsteps, like Devorah Sperber, who creates painting-sculpture hybrids that loosely reproduce famous images in odd and surprising materials. And he is popular with the mainstream media, who like to use his photographs for editorial projects. The New York Times has long worked with him for magazine covers and inside fashion and art spreads. Esquire recently commissioned him to create a portrait of Vladimir Putin—in caviar, naturally.

“My art is about the conflict between mind and matter,” Muniz tells me. “It’s about seeing the material and the image and the way they don’t connect.”

Does this mean he has lost his bite? Has Muniz become more of a court jester than a genuine outsider? Not necessarily. Playing in commercial fields and pleasing the masses comes naturally to him in part because he has a background in advertising. In 1980, at the age of nineteen, and after graduating from a high school arts program in Brazil, he says he began to notice how poorly designed the billboards were in Sao Paolo. “I remember one advertisement for a toy doll, on a billboard that was positioned very low, on the drivers’ side of the road, with a long text printed in a tiny font, along a high-speed highway around the racetrack—and thinking: ‘You’d have to be a tall, driving, horse-loving, speed-reading baby to be interested in that doll,’” he writes in his book Reflex: A Vik Muniz Primer. He started computing how to improve the legibility, positioning, and design of these billboards and took his ideas to an outdoor advertising company, which hired him as a consultant on the spot. Later that year, he joined the staff of a small advertising company at the invitation of a client. But he realized he wasn’t that interested in selling products; he wanted to sell ideas.

Muniz is very fond of the joke—the paradox—in his own (often well-rehearsed) stories about pivotal events, including the tale of how he left the advertising world and crossed over to art. As the story goes, it happened because he got shot. Leaving an advertising awards ceremony one night in Sao Paolo, Brazil, he tries to break up a fight, and one of the men involved ends up shooting him in the leg. “Luckily, it wasn’t fatal, as you can see. And even more luckily, the guy said he was sorry and I bribed him for compensation money,” Muniz told his audience at a talk in 2003 at TED, an annual conference on new ideas in technology, entertainment, and design. “With this money, I paid for a ticket to come to the United States in 1983. And that’s the basic reason I’m here talking to you today. Because I got shot,” he says, with deadpan delivery. It’s a tale he tells often to journalists, and one he tells in his book Reflex, too. In the telling, the rest of Muniz’s evolution from award-winning ad-man to internationally renowned artist is secondary to the tale of near-tragedy turned deliverance.

His advertising roots have served him well, though, acting as a stand-in for a larger idea Muniz is trying to subvert: manipulation through information. He grew up under the dictatorship in Brazil in the nineteen sixties and seventies, at a time when information was traded on what he likes to call the “semiotic black market.” The government controlled all forms of communication: radio, television, newspapers, artistic expression. Everything you said had to be carefully coded to convey meaning: love songs were often meant to be scathing critiques of the government. “In terms of how I relate to things, I think the dictatorship was my most influential school,” he told me recently in a telephone conversation. “When you cannot trust information you receive because you have censorship, and the government controls communication, and you cannot say what you want to say, you have to say it through metaphors. All that information becomes very elastic and you start looking at information—you start really analyzing its mechanisms, its parts. Everything is custom-made.” Tricksters, by their nature, need powerful forces to oppose and pull asunder. The dictatorship seems to have provided Muniz with that initial impulse. He continues: “Today I can look back and say that. I hated the dictatorship, but without growing up in that kind of environment, I wouldn’t have the same intellect, and I wouldn’t be as cynical of information as I am today.”

For inspiration, Muniz drives around Brooklyn and surfs the Internet, often starting at places like McSweeny’s or Cabinet magazine: he likes the sense of visual overload in both experiences. “I was born in a huge city in a very confused place, with thirty million people,” he says. “My senses were always over-flooded with input, and I feel very comfortable in this. I can be in the middle of traffic and I’m very focused. That is somehow the way I picture the real world. It’s a very autistic experience.” He tries to look at everything from graffiti to cave drawings to advertising, he says. “Because I think you start cutting yourself short when you say, oh, I like this, or oh, I like that. It’s not about liking one thing or another, it’s about making sense out of the whole thing.” He is a constant traveler in a vast landscape of representation, and he wants to reveal its magic. “We grow very numb to the devices that enable us to understand the world,” he says. In today’s visually-saturated culture, images have lost their power to inspire awe, and Muniz is trying to put it back. But unlike the Wizard of Oz, he wants to let us peek behind the curtain to see how he creates his effects.

Perhaps Muniz lets his viewers see behind the curtain too much. After all, most magicians will never perform the same trick twice, at least not for the same audience. And yet Muniz is sometimes criticized for rehearsing the same idea over and over again in new materials. Other artists have done this in the past, says Shamim Momim, a curator at the Whitney Museum of Art—she mentions American painter and minimalist Robert Ryman as an example—but in today’s art world, a constant search for the new makes it more problematic. “I think that is one of the problems with art being more popularly available. It ends up having the same ideas as mass media or celebrity applied to it. It’s an endless search [for what is new]. It’s like, oh, I’ve seen that, so that means it’s done.”

Tricksters, by their nature, need powerful forces to oppose and pull asunder. The dictatorship seems to have provided Muniz with that initial impulse.

On the other hand, Muniz’s tricks are evolving, getting more complex: his projects are increasingly ambitious and lately seem to require an impressive theatre of production. Many require months or even years to produce. Here, he makes his success work for him, leveraging his top dollar prices into art that would otherwise have been impossible to create.

In one 2002 series, called Earthworks, for example, he married land art with pop art, movements that were happening simultaneously in the nineteen seventies but had not been brought together until this work. Over a period of four years, using mining equipment, Muniz and a team of assistants carved simple line-drawings of mundane objects—scissors, socks—into the earth at an ore-mining site in central Brazil and then photographed these drawings from a helicopter. At 600 by 400 feet, some are larger than the centuries-old Nazca drawings in Peru. Looking at his coarse renderings of utilitarian objects in such epic scale is both disconcerting and hilarious. These drawings (if you can call them that) manage to invest the sacred (vast landscapes, mastery of nature, the monument) with a touch of the profane, and vice versa. They suggest, simultaneously, that we give the objects of our every day lives too much power, and not enough. “Both [land art and pop art] talk about very mundane things,” Muniz tells me. Whereas the land artists drew forms occurring in the natural world, like lines, spirals, and triangles, the pop artists were making art about cans of soup, Coca-Cola bottles, and other manmade objects. They wanted to demystify those objects, as well as the tradition of abstract expressionism, he says. Once again, he spins that around: by rendering modern artifacts in such scale, he makes them mystical again, while simultaneously poking fun at the reverence afforded to the ancient earth markings from earlier eras.

In another series entitled Aftermath, he recreated photographs of homeless children in his hometown of Sao Paulo, whom he befriended over a period of several months. These children are practically invisible—dusty and dirty, they blend into the city landscape, and they are largely ignored by the culture that has produced them, he has said. He asked them each to pick a portrait they liked from an art history book he brought with him, and then he took Polaroids of the children wearing, after some rehearsal, the same poses and facial expressions. He then recreated those photographs using the detritus left on the streets of Sao Paulo, the day after Carnival, which he had carted back to New York: “confetti, bottle caps, tinsel, discarded costume fragments,” he writes in Reflex. “I also decided to work in negative: representing the children in shining light through the dirty residue of excessive behavior. I wanted to invent a mimetic environment in which these beings are perceived and not perceived simultaneously.” In the images, the children look like angelic ghosts, making themselves visible only through the force of their own creative impulses. You can “see” their fragile mortality. (The proceeds from the project went to fund Muniz’s own charity arts program, Centro Espacial, for poor teenagers in Rio de Janeiro.)

Muniz says he sees helping people untangle the way images work as almost an ethical responsibility. Part of his project is to get people to “read” images—to learn how to resist the potentially pernicious stories they tell.

In fact, Muniz, who has a three-year-old daughter and an eighteen-year-old son, confesses a special fondness for kids. His captivation with them is no accident. Like the trickster of myth, he gamely plays the wise fool, the grown-up child. He takes his ideas very seriously—books about perception, psychology, and cognition fill his bookcases and sit in tidy piles all over the room, he is a member of TED, and he is close friends with theoretical physicist Lee Smolin and other scientists. But he often refers to his materials as “stupid” or “dumb,” and says that children are his ideal audience—as opposed to art critics.

His antipathy towards critics might be warranted, to an extent. As often happens when an artist becomes wildly popular—and especially right around the time the artist puts on a retrospective (as Muniz did in 2006)—there has been some critical backlash. In a funny way, the critical response to Muniz imitates the very conflict at the center of his work: he’s attacked for being gimmicky, easy, lacking in depth—a response that could itself be criticized for being gimmicky, easy, lacking in depth. Critics deplore his populism, as if reaching a mass audience were evidence of failure. “Despite the enormous skill, cleverness, and work ethic Muniz invests in the images, that gamesmanship comes through louder than everything else,” writes Franklin Einspruch in a review of Muniz’s retrospective, in the Miami Sun Post in April 2006. “The gamesmanship passes for an art experience by virtue of its scale and its mining of art history.” To which an appropriate response might be: hate the game, not the player.

Muniz shrugs off such criticism, offering as a response a trickster’s riddle: “Depth is an illusion, because if you dig a hole, you think you are going deep into something, but you actually get twice the amount of surface,” he says, a bit coyly. “I dwell in the realm of surfaces and I am a superficial person.” That said, it does seem to bother him that some people don’t see beyond the surface and the materials. “Sometimes I’m annoyed when the discussion doesn’t go beyond that,” he says with a frown (the afternoon’s first). He really wants viewers to think—in the broadest terms—about the power and magic in representation, and to explore deeper questions about how the materials inform the subject of the work.

Muniz says he sees helping people untangle the way images work as almost an ethical responsibility. Part of his project is to get people to “read” images—to learn how to resist the potentially pernicious stories they tell. His old medium, advertising, is his primary foil. “I’m not making images to compete against other contemporary artists,” he says. “I’m making images to compete against, you know, dishwasher soap boxes and television commercials and car dealership flags, and I’m thinking about how these things exist in the context of the entire visual experience.” He hopes his work acts as a counter-agent. “In effect, they make the poison. I’m supposed to make the vaccine. I use the same poison they make, and my idea is to make antibodies,” he says, with a grin.

And here, again is the knotty paradox: he does and does not want viewers to get caught in the surface, in the “stupid” questions. All the visual power, the fun and games, are really a trap: once the viewers are caught, he wants to set them free.

Kristen French is a writer living in Brooklyn. She has been a business journalist and editor for over ten years in New York and Santiago, Chile. She is currently a student at the City University of New York in The Writer’s Institute program.