At that time it could be said that we knew many of the horses in town on a personal level. With little effort I could have told you who owned each one, how they were related to each other, and also what dispositions they had, which ones would let you stroke their velveteen noses and feed them apple slices and which ones my father had told me were known to bite. No doubt the reason we knew the animals so well was because my father was a vet, and so his life and our livelihood were fundamentally entangled with the lives of other creatures. On the days when I was home sick, he would tell me stories about the animals that were his patients, the secret ways in which beings without language could disclose their pains, how he had nursed them back to health, and the lives they had led to fullness afterwards. My engagement with animals was far deeper than that of other children who loved animals but who imagined them mainly through the lens of fables, which after all were stories molded in the form of human society, and gave no thought to animal ways. In the same manner, I referred to the dogs and chickens and pigeons my uncles kept as my cousins, and if my father smiled to hear this, he never corrected me, and I meant this not as a figure of speech but very seriously, because excluding something from the category of family simply because it wasn’t human made no real sense to me. And so I did not believe my Orthodox neighbor when he told us that man held kingship over all animals, and as he explained about the infinite benevolent blessings of Christ, I ran away from him and could hear him cursing me as I did so.

And in the winter in those days, lemons became more expensive and oranges became more expensive and limes became prohibitively expensive and what tomatoes we could find at the market were anemic in color, all water and tasteless, mealy flesh, and to me the yellow-green seeds suspended in jelly that spurted out at the first slice of the knife resembled a thousand insectoid eyes, and I hated them and refused to eat any tomatoes until they were cooked and mashed down into an unrecognizable eyeless paste. Before first frost our father would gather bunches of the herbs in our garden and hang them to dry around our kitchen so that all winter long the hot little room was suffused with the smell of a sunny field, and sometimes I would stand in the kitchen corner and close my eyes and be very quiet while the scents came over me, and when I breathed in, I got the feeling that I was in another time and place entirely, and once when my father had come home from his practice early and entered the room without my hearing, I opened my eyes and saw him staring at me curiously, and before he could say anything, I blurted out: In here it’s still the springtime.

My mother hated buying out of season and had a grocer’s daughter’s inborn sense that produce had an ordained time, and so what we had on our plates cycled with the months. I sometimes thought that I could feel the world becoming part of me as I ate, the heat that brought the June melons to sweetness, the warm rains that fattened the peas on the vine, and the cold soil out of which the carrots and beets of our winter table had drawn what minerals they could before being dug up, and with each bite I imagined the rude elements of what I ate flowing through my body and down to my extremities, building up my strength brick by brick.

As a child I felt that the boundary between my body and the world was fuzzy and ill-defined, less a wall than a shoreline whose boundary was redrawn from moment to moment. At night my father would read to me from books of mythology from China and Babylonia and Ancient Greece, and what I heard I sincerely accepted as history, and if the contradictions between one account of the earth’s beginnings and another troubled me, like a riddle I did not yet know how to solve, there was one element that remained constant: that of humans made from clay, lifeless stuff scooped up from a riverbank and rendered animate by a breath or a thunderbolt or the warmth of a holy hand. This all made an intuitive kind of sense to me. I had heard about pregnant women seized by the urge to eat mud and imagined that the babies growing in their stomachs were the result of the slow accretion of the life-giving dirt that these mothers consumed. Around this time, I was prone to bouts of anemia serious enough that I would sometimes faint on the playground and be sent home from school. My father was usually the one to care for me on those days, and as I lay pale and woozy on the sofa under a quilt, he would prepare a slurry of rice in a pot with a little iron ingot shaped like a heart. And when it was ready, he would help me sit up to eat, though in reality I was probably not so weak that I could not have done it myself, and he would give each of my blue-nailed fingers a squeeze to put some warmth into them before I picked up my spoon. Secretly I cherished my illness, how it made my body the subject of almost worshipful attention from my father, as though it was not entirely my own but a thing held and protected in common. And evening would come, and he would give me a stout-colored iron drink before bed that made my stomach clench up and turned my stool black and hard as an untilled field as I cried over the toilet from pain. My parents would feed me bran cakes or mashed bananas (and these, too, became very expensive in winter) in the morning to counteract the constipation, and it seemed that illness and health were not two opposite binary states but that the road to health engendered many further sicknesses, and sometimes in contemplating these, it seemed like the effort and pain good health required of me were simply too great, and it would be better to sink down into the hole of my illness, which in its familiarity at least offered an obscure kind of comfort. I hated my medicine, not only because I sensed that getting better meant having to leave the special island of parental love reserved for sick children, but also because taking it filled my mouth with a strange and familiar taste, and it was a long time before I realized that the flavor was that of blood, of a split lip, of a ripped-out tooth, of a horrible gaping wound. And so as I swallowed my tablets, I felt that I was eating my own body, and I felt that I was eating the earth, and I also believed that at the root there was no difference between these two things, and I thought of the pregnant women and of the earth babies slowly forming in the kiln of their wombs, and I wondered if there would come a day when I would give birth to a child formed of iron, and how would that be, and what if it rusted, and would the baby be able to grow, or would it be forever small and dense and solid, like the little ingot my father used when he prepared my special rice? Yes, I understood completely that I was a person made of clay. I felt it as I played in the muddy school sandbox after it rained or as we mounded up sculptures in our art class at school, and the idea of returning to the clay, as our Orthodox neighbors so solemnly put it when they tried to spook me and my sister into coming to church with them, did not fill me with dread but with an oceanic peace, because I sensed that being buried was no kind of death at all but a state of being surrounded by and mingled with the stuff of life itself.

And winter was the season of ginger and cinnamon and allspice and cloves, and given how unimaginable a December without them was, it was difficult to accept that these things were not native to our part of the earth but came to us from far away, and that there had been a time before them and there might come, conceivably, a time when their use would fall out of custom. And in winter my mother showed a strange predilection for black pepper in sweet things, in cakes and above all in tea, which made my father tease her and call her a witch. And winter was also the season of frying, of onions and potatoes squealing when they hit the grease of the pan as the water was sizzled out of them, and the feeling of oil on our tongues and lips as we ate, oil that gave my older sister a pink constellation of acne around her mouth, however fastidiously she scrubbed her face before bed. But I was too young then to bother with these things, and as my sister sat despondently blotting her chin with her napkin, I ate with abandon, like a wolf cub, as my father used to say, or as if I had survived a great famine, and I remember at least three separate times in my childhood where I inhaled a half-chewed bit of food and my father had to pound me on the back or the stomach to force it up again, and if I had been alone in the house on any of these occasions, I would have choked to death before the age of ten.

Hot food for a hard season, hot tastes to put a bit of fire in the belly, even as the cold constricted what would appear on our table. For other families it meant roast turkey or perch or hefty stuffings of bread soaked in chicken stock and generously interlarded with sausage, but this was not so for our house because we possessed a very strange trait for that time, which is that our father was a vegetarian. Our Orthodox neighbors sometimes abstained from meat and dairy for weeks on end as part of their complicated cycle of religious fasts, but for them, as they explained to me on one of the many occasions that they tried to save my soul, it was an act of instilling remembrance of their god through a measure of bodily suffering, and the very idea of vegetarianism as a prescribed form of penitence seemed to mark it out as an aberrant and fundamentally lesser state of being. This was completely contrary to my father’s understanding of vegetarianism, which held the refusal to eat meat to be a natural and necessary extension of a humanistic outlook. It was neither a way of delimiting sacred time nor a torture to be taken upon oneself as a scourge against worldliness, but merely how a person must always be. He never forced his diet on us, and our mother still sometimes cooked meat at home, though she had gone so long without consuming red meat that it lay too heavily on her stomach, so she restricted herself to fish and, occasionally, a bit of shredded chicken. Likewise, he always permitted my sister and me to eat meat, though he did not look particularly happy when he saw us doing it and would sometimes excuse himself from the room on account, so he claimed, of the smell. Still he said it was our own decision to make, and such realizations about right or wrong could only come from within a person and not from an outside authority. For all of that I rarely ate meat, and when I did it was usually because it was presented to me in some strange and unrecognizable form, crumbled into gravelly bits of topping or pressed and extruded into homogenous pinkish pancakes of deli cuts and offered to me by a classmate at lunchtime. So if our father’s rearing did not force us into vegetarianism, his influence did at least allow us to see that eating meat was not the default option whose refusal was deviant and therefore required explanation, but a choice in and of itself to which saying no was as natural as saying yes.

I heard many in town call my father a rebellious spirit, some in appreciation and others in scorn, but there is a part of me that thinks that if my father could have been any other way, he would have, that it was not his desire to defy the ruling order that led him to adopt unpopular stances but his convictions that forced him, even against his will, to oppose convention. For my father saw the world made always of flesh: beer fermented with the swimming bladders of fish and wine cleaned of its impurities using gelatin, rennet scraped from sheep stomachs and used to harden cheeses in their molds, chicken and duck feathers turned into powder and added to bread to help its rising, and beef fat added to car tires and bicycle tires to stiffen them and used as a binder in the asphalt on which they drove, bones ground down to whiten china or burnt to ash and used to purify sugar, and pig grease and cow grease used to help crayons glide along the pages that themselves contained traces of animals, which was to say nothing of the notebooks bound with animal glue or the brushes that used hog hair bristles or the paints that needed fat for their gloss, and plastic bags contained fat, too, so that they could unstick from each other, and electrical parts were coated in fat to stop them from overheating, and the fabric softener with which our parents did the laundry contained tallow from sheep to give our towels their special fuzziness, and pulverized beetles were added to my favorite candies to give them their blood-red color, and ground fish bones lent my sister’s nail polish its shine, and my toothpaste contained bonemeal and my shampoo contained cow horns and cow hooves, and my mother’s perfume obtained its faint vanilla scent from the secretions of a beaver’s anal glands, and cow blood was in cigarette filters and egg-free cakes, and they boiled pig tendons and pig skins and pig ligaments to slow ice cream’s melting and make camera film, and they used intestines to string tennis rackets and cellos, and extracted insulin from pigs to put it into diabetic humans and carved up bits of their hearts for use as surgical implants, and animals were also connected to our death, in the pig bone gelatin added to bullets and in the pig skin with which they tested chemical weapons in secret government labs to better understand how to kill. And if others saw a kind of virtuous absolution in this use-every-part attitude, my father saw the meat industry’s ability to tentacle its way into ever-expanding corners of the manufacturing world as a kind of deadly reliance from which it would be impossible to extricate ourselves. And if my vision of myself as clay gave me a sense of power, then my father’s vision of the world as flesh did the opposite: it took his power away from him and made it sometimes very hard to stay afloat in a conversation, rather than retreating into his private reflections about how every one of his actions, despite his best virtuous efforts, was predicated on mechanized killing at an almost unimaginable scale, and there was no action he could take in tenderness or wrath that was not limned by the specter of death.

I thought of my father when I first saw a butcher’s chart of the cuts of meat, and the lines delimiting chop from sirloin, rump from chuck, seemed just like the borders on the maps in my classroom, and it seemed to me that whoever drew or possessed such a chart could not in a meaningful way see these animals as living things, but more like territory to be conquered and over which to assert a king’s dominion.

On occasion my father did see pets at his veterinary practice, and a couple times a year he would gather the street cats for spaying and neutering in an attempt to curb their numbers, but most of the animals my father treated were livestock, some on small farms but others, increasingly, from the factory farms whose owners we did not know and whose buildings we were not permitted to approach. These animals, as he put it very plainly to us, lived short, blunted, cruel lives, and my father provided little more than palliative care before slaughter. I never had the chance to ask him how he felt about tending to animals from these farms, whether he thought that at least some dignity could be given to their lives by easing their pain, or whether he sometimes had difficulty reconciling himself to the task of abetting a system that he opposed. In any case there were evenings when upon returning from a farm visit he was very quiet. Watching him from across the dinner table, I felt a peculiar sort of pride that I would only come to understand many years later — a pride rooted in the fact that it takes strength to continue feeling, to preserve always within you the sharpness of an old wound, and that after so many years as a vet my father was able to feel pain at what his work demanded of him.

But I still hated my medicine — hated it, hated it, hated its wound taste and hated the idea of getting better, of going to our cold gray school with its cold gray teachers instead of staying home with my father, who loved me and whose strange and remote sadness, so I imagined in my child’s narcissism, could be healed, in turn, by my love. I put the pills in my pocket or threw them down the toilet. I poured the iron drink into the flowerpot. I spat cheekfuls of my rice slurry into the sink. Anything to be rid of it. And if my father thought I was well enough, he might even take me with him on his farm rounds and leave me to ponder the slant-pupiled eyes of the goats while he went to tend to his latest patient. And the farmers would try to give him sides of bacon, which he refused, or sausages they’d made themselves, and finally they might settle on a bag of eggs and a bundle of fresh cheese, and on the car ride home, as I drank a bottle of cowmilk or ewemilk still warm from the udder, I thought how different it was from the blood drink of medicine that awaited me at home that evening.

And my parents took me to the doctor for a look at my heart, and my father boiled my porridge with two iron ingots instead of one, and my skin went pale, and my hair grew thin, and my nails became bark-rough and ridged. At dinner I would chew on the ice in my water glass, as though it had any nutrients to give me, and my father would rub my shoulder and say, Let’s keep you home from school tomorrow, and he would give me another tablet that I would hide under my tongue until I could be excused to go to the bathroom. Falling into the well of my illness, falling down into sleep and rising faint if I stood too quickly, and on the worst days, my father would have to call the clinic and say he couldn’t go in, and that is what happened the day the horse died.

I knew this horse: a pinto mare whose white-splattered sides made it look like it had been run through a puddle of cream, with a bald face and eyes drained of all color except the palest blue tinge that gave the animal the appearance of being blind. I had seen this horse many times at the riding games they held in the field out past the town limits. It was prone to bucking and tossing its head wildly, to flaring its pink nostrils and gnashing its yellowed teeth; it seemed not to like the company of so many other horses at once and could only be brought into the games ring with great difficulty. Perhaps it was those strange eyes that gave me the impression of wildness, that made it seem fierce and mean when in fact it was only afraid. And I knew that this horse had had a foal that died, a little one born all white in a way that, so my father explained to me, was associated with deadly problems of the internal organs and required him to kill it out of mercy on its first day of life.

The mare died in winter. My mother had taken my sister out of town to attend a mathematics competition, and I had been pitching my anemia medicine whenever I could, despite the starry feeling in my head for months, by that point, and as I feebly poked at my lunch, my father sat listening to the owner of the dead horse talk to him on the phone about how my father hadn’t come for the creature, how the horse’s colic could have been cured, but as it was, the only thing to be done was to put a bullet through the creature’s head to stop its suffering from the knots it had tied in its stomach, and as my father watched me finish my soup, he absentmindedly stroked the petals of the potted flower on our dining room table, stroked the leaves and said, Yes, yes, no, I’m very sorry, stroked the shoots and said, My daughter’s very sick, and when his fingers reached the base of the plant, they met what he must have at first thought was a perfectly pill-shaped stone but which he saw, on inspection, was the iron tablet I had pressed into the dirt as he turned his back to make his coffee. He turned it over between his fingers, over and over as he spoke, turning his thoughts over too, looking from me to it as the farmer poured his sadness and anger into his ear, and my father thought of the world and the flesh, of the iron and blood, and without my needing to say anything, he understood everything, and for my part I understood that my evasions had finally been discovered.

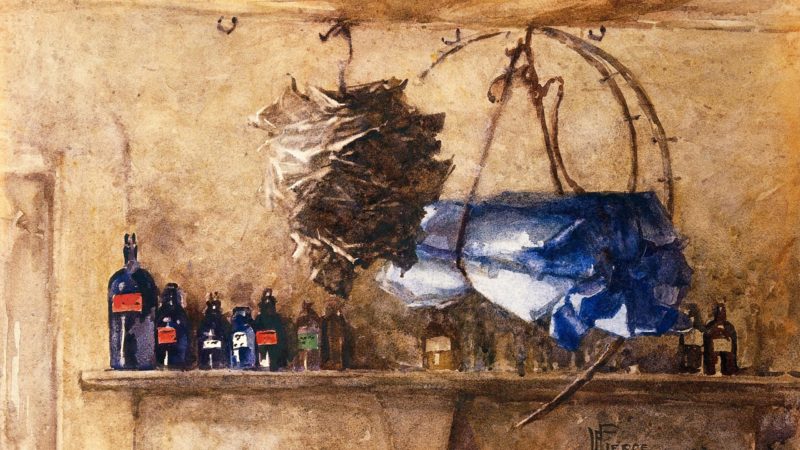

That evening he asked the Orthodox neighbor to mind me, and when he came back to get me, he was carrying a plastic bag full of meat from the horse that I had killed, a horse whose eyes I can still picture and whose angry snorts I can still hear. The Orthodox neighbor gave him a strange look, as if unsure whether my father had gone mad or at last come to his senses, but my father offered him no grace of explanation, merely beckoned for me to return. The meat was darker than beef and had a leaden smell, and at the bottom of the bag lay a liver, shining in the light like a fish, and bones too, with which, my father announced, he intended to make a kind of stock, so as not to waste anything. The bones I remember very clearly: up until that point the processed flaps of meat I’d eaten sporadically over my life had never really confronted me with the physicality of butchering. Perhaps this is why so much of the meat fed to children is patties and extruded bits: to inure them to what meat is and what its harvesting requires until it has become too familiar to shock. And now my father uttered his first words of acknowledgment: You did what you did for all that time, he said, and now you must own the consequences.

And when my father began cooking the meat, the air was filled with such a smell of fat as it popped and splattered against the counter and against the wall and against my father’s hand so that he had to press his burnt finger to his lips, while with the other hand he used a spatula to scrape the burnt bits at the bottom of the pan, and now the scent of high summer was gone from the kitchen, and even if I closed my eyes, all that could be smelled was the smell of that winter, that moment, and as the beads of grease on the wall glinted in the light, I felt that I understood something of my father’s view of the world as flesh, and I wondered if those grease marks would ever come out or if they would always be there, always reminding me of what I had done. And as I stood in the kitchen watching my father cook, I felt a certain distance between us become calcified and uncrossable, the distance between us that I had only ever tried with my sickness to reduce, and I cried pitifully, but it was as though he didn’t hear me. Let no one say my father was not a man who did not take his tasks to completion. When he put the plate in front of me, the meat was still dripping with what my father clinically informed me was not blood but water mixed with muscle protein, though what, in truth, did it matter? And with each forkful I felt my memories being overwritten against my will so that the season of ginger and cloves was becoming the season of horsemeat, of mare steaks, of flanks cooked in juices and the bones left to simmer, and like the ground beneath my feet, the way I understood myself began slowly at that moment to shift: the beginning of my realization that I was not only a separate entity from the earth and its creatures and my family, but that I was capable, even despite my own best intentions, of grave malefaction.

This was a first and terrible lesson.