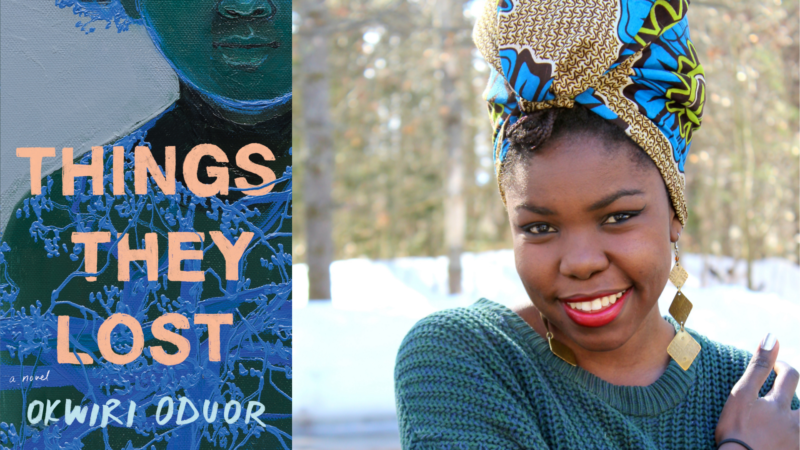

Okwiri Oduor first came to prominence in 2014, as the winner of the Caine Prize, Africa’s most prestigious short story prize. In her winning story, “My Father’s Head,” Okwiri’s narrator struggles to bring to mind a full image of her late father and listens instead to his obituary on the radio.

Now, in her first novel, Things They Lost, Okwiri veers around stretches of spectacular prose to explore themes similar to “My Father’s Head.” Things They Lost is the story of Ayosa Brown, a thirteen-year-old girl living in the fictional Kenyan town of Mapeli, which sits on land given by colonial authorities to Ayosa’s great-grandmother, Mabel Brown, an English settler. Ayosa and her mother, Nabumbo Promise, struggle to patch up their relationship, all while dealing with several secrets in their family. Ayosa makes friends who compensate for her mother’s absences — the Fatumas, faerie-like creatures who keep her company; Mbiu, a throwaway girl who has been abandoned by the town; and Sindano, a lonely woman who understands Ayosa’s struggles with her gift: Ayosa is omniscient and knows things that happened before she was born. It is a story about mothers and daughters, of daughters who become mothers to daughters who become mothers, and a story of girls who are abandoned and alone, of girls who find family in other lonesome girls.

It is also the story of how death permeates our lives. In the novel, people in Mapeli struggle to remember their dead, either by celebrating them on Epitaph Day, a special holiday for this very purpose, or by listening to radio obituaries, the announcer leading them in their sorrow.

There is a brazen Kenyan-ness in the text, the characters drinking brew at Mama Chibwire’s parlor and dancing along to “It’s Disco Time” with Samba Mapangala & Orchestre Virunga. The novel is set in late 1980s Kenya, as the 24-year dictatorship of Daniel Moi unfolds. Economic liberalization and Western-backed structural adjustment programs have led to widespread joblessness, frequent strikes, the collapse of public services, and heightened inequality. At the same time, political persecution and organized crime create an environment where disappeared people become a norm.

Things They Lost wrestles with how these changes are processed collectively, a complex combination of celebratory remembering and willful forgetting. Okwiri and I speak about how, both in the novel and in the Kenya where we grew up, this atmosphere translated into the register of mythology and rumor, where mysterious body-snatching wraiths ran amok.

— Carey Baraka for Guernica

Guernica: The Brown family, the family around whom most of Things They Lost revolves, owns a huge chunk of land in Mapeli, land which was grabbed by colonialists and given to Mabel Brown. Even in the present time of the novel, they are still very privileged. They have all these things in their house which most of the other people in Mapeli Town don’t seem to have. Why set the story there?

Okwiri: The family lives in this humongous house that Nabumbo considers gaudy and ugly, but Ayosa doesn’t think of it as wealth. It’s a resting place for shadows. It’s a resting ground for what was there before, like these aristocratic ambitions, this terrible woman Mabel Brown, her daughter who was terrible as well, and this intergenerational isolation from the rest of the community. They tried to maintain this wealth, but now it’s crumbling, and there’s less of it with every passing generation until in the end, it’s Ayosa looking around her, and she’s just the loneliest girl in the world, and the house feels like a prison to her, and everything’s just falling apart. It’s not a mansion anymore. It’s just a really poorly renovated decrepit ugly thing that they live in.

Guernica: The entire town of Mapeli keeps secrets. Everybody has all these stories which nobody talks about. Why is this town so heavy on secrets?

Okwiri: I think the interesting part is that they pick and choose whom to punish for their secrets. Not everyone gets punished. For example, the priest and Dorcas Wanyonyi get away with their scandalous secret but Sindano, and Nabumbo and her family, don’t get away with theirs. They have to carry them and are shunned for it. There is generational trauma built up through such communal nailing on the cross. The town listens to poetry on the radio because it helps them come to terms with this, helps them see the roles that they play in other people’s grief or trauma.

Guernica: There’s a part where Miss Temperance, the radio poet, was sick and couldn’t read her poetry on the radio, and the townspeople threw a Molotov cocktail into the radio station. That’s them saying, “We need our therapy.”

Okwiri: Yeah, exactly. Therapy is exactly the way I would consider it. Maybe it’s not specifically the character of Miss Temperance that’s important here, but the role of art and poetry, the role of literature in our lives, how it helps us come to terms with our own humanity and make sense of terrible conditions, of The Human Condition. But also the beauty of it makes our present very tolerable. I can’t imagine where we would be without art. It’s so heavy right now. Can you imagine not having music or art, or films to look at, in order to be able to carry the weight of the world and figure out ways of moving forward?

Guernica: Ayosa is, in essence, carrying the collective trauma of her mother, of her grandmother, and of the entire town — this cascading female loneliness. How is she, as young as she is, able to do all this? I imagine a person would crumble.

Okwiri: She talks about it with her mother Nabumbo. There’s this part where Ayosa is in the car with her mother, and Ayosa is writing in her notebooks saying that someday someone will want to know what it’s like to be a girl, and she wants to remember. So she’s writing it down, and her mother asks her, what is it like? Your girlhood, what is it like? And Ayosa says, it’s lonely. And the mother says, every girl I ever knew was lonely, what is your specific lonely like? And Ayosa says, there are memories in it, and she explains some of the memories. Like this prehistoric memory of what it felt like the first time the sun warmed the frost on the ground. It’s really beyond the memory of herself before she turned into a girl, going into the memory of Mother Earth in her own girlhood. And her mother reacts to that saying, you know, that must be extremely heavy. And Ayosa says, it’s incredibly heavy.

Guernica: Mabel Brown came to this country as a colonial settler and was given this chunk of land as a 999-year leasehold. And it’s that thing of “Oh, nobody was here before her” so the town is going to be called Mabel Town. But over time, the African inhabitants of this town start calling it Mapeli Town, telling themselves that this new name is a way of owning this town, that it’s not Mabel Brown’s anymore. I wonder, is this logic sound? Or is it them deluding themselves that they own this town?

Okwiri: It belongs to them. It belongs to them more than it ever belonged to Mabel. I was just thinking of how, for example, all my life, until I was an adult, I never knew that Lake Victoria was called Lake Nyanza before that. We had our own names for these places until Speke renamed them in 1858, but our “history” always starts with white settlerhood and colonialism and conquest. Beyond that, we’re just the Dark Continent. We have no histories before the white man arrived. So I think this is their way of reckoning it. Ayosa, as much as she’s a child, is also a discerning and wise spirit. She questions this history and asks her mother about it. And her mother says no, there were people here before that, but these people are as yet nameless, because we don’t think of them as a people that lived and breathed and had a culture with songs and traditions and oral histories. On a personal level, I have no idea about the histories of my people from beyond two generations before me. I don’t know what the lives before my grandparents were like. By calling it Mapeli they are not deluding themselves. They are being subversive and saying, in this town, we refuse to see ourselves through the entry point of the white settler. Even though Mabel was her name, Mapeli is what fits in our mouth. The history continues. It does not start here, but it continues from here.

Guernica: But a person could also argue that this place had its name before Mabel came into the area, and that original name is, in essence, lost. The inhabitants don’t know the original name. So even as they try to reclaim it, they are not actually able to reclaim what was there before Mabel arrived, are they?

Okwiri: Maybe that’s not what they’re trying to do. They’re not trying to reclaim it, but to recreate something that’s for them, something that says that the story continues: that, while that part is lost and we can’t get it back, we honor it and continue forward in a way that resonates with us, that feels honest and truthful to who we are as a people. Defining ourselves towards Mabel Brown is not truthful to us. What feels truthful is to take Mapeli and to make something new of it — which recognizes that something traumatic happened, that we broke off from what was there before, but we still connect with it through this memory, and we have something new.

Guernica: One of the things that makes Ayosa’s loneliness easier to bear are the faerie-like Fatumas, who used to be in servitude in Mabel Brown’s house when she lived there and aren’t anymore, but they can’t go back to where they are from, the Indian Ocean. The presence of the Fatumas and the wraiths is one of the ways the book is infused with Indian Ocean mythology. Ayosa is living in this decrepit ode to colonial aristocratism, but she also has these guides from a pre-colonial spiritual realm.

Okwiri: I think I was trying to pay homage to some of the mythologies that surrounded me when I was growing up. I wouldn’t necessarily tie it down to Indian Ocean mythology alone. For example, I’m thinking of Lake Victoria again, which is where my parents come from. I heard this story about a man called Nyamgondho. He was a poor fisherman on Lake Victoria. One day, he fished a woman out, and the woman brought him much wealth — cows and goats and sheep and all of that. But then Nyamgondho was proud and abusive to this woman. Because of this, she left. As she was leaving, she played her nyatiti. The animals heard this music and followed her back into the water. This is just one story. I was surrounded by such stories growing up. The Fatumas come from the Indian Ocean, but there was a smaller ocean in the hinterland where people also came out of the water and returned to the water. The Nairobi that I grew up in was extremely multicultural. We were surrounded by so many different ethnicities, each with their own set of histories and narratives. I hesitate calling them mythologies because that sounds like myths; when I was growing up, these stories were very much a part of reality.

Guernica: I grew up in Kisumu, and in 2007 there was a jini in Kisumu. Thinking back now, I wonder if it had something to do with fears about the coming elections. Once, the headmistress called an assembly to assure us that there are no majini in Kisumu, but that just made it more real.

Okwiri: Do you remember, around that time, in some girls’ high schools there was hysteria of some kind and people were having fainting spells? The explanation was that there were majini in these schools.

Guernica: It’s like the Tanganyika Laughter Epidemic of 1962 that happened in several schools around the time that the country was gaining its independence from Britain and becoming Tanzania.

Okwiri: Yeah, it’s similar to what was happening in these high schools in Kenya, that there were mass hysterical episodes happening in schools.

Guernica: Of course “mass hysteria” casts a certain tint. But it seems to be what is happening with the people in Mapeli. People are being attacked by wraiths which are trying to snatch their bodies.

Okwiri: Did you have these types of stories surrounding you when you were growing up? We would be warned that if you hear someone calling your name, don’t answer unless you know who it is, unless you can see them, because it could be a genie trying to snatch you. So for me, it’s mythology, yes, but it was also very much a reality. Maybe part of it was that people were stealing children. So it was a way of framing that in a way that kids could understand.

Guernica: I wondered whether the reports of people being snatched in Mapeli were an allusion to 1980s Kenya, where there was a lot of murder, a lot of people going missing, a lot of people being kidnapped and disappeared.

Okwiri: It was an allusion to the fact that there were a lot of unexplained absences. I remember, in the ’90s, there was this fear of speaking up. Shopkeepers were afraid of letting the president’s portrait get dusty on the wall because you don’t know who is watching and how they will interpret that. It was a time of great fear and secrecy, of families torn apart when someone disappeared. There are missing bodies everywhere in this town also, and people are trying to make sense of it.

Guernica: With some of the missing bodies in Mapeli, there is this dissonance: wraiths are snatching bodies and people are sad about it, but then at some point those who go missing are forgotten. And the town seems to be forgetting these people on purpose.

Okwiri: I was thinking about the violence that was there when I was growing up. For example, the Wagalla Massacre, which was mostly just forgotten. [In 1984, the Kenyan Army forced thousands of Kenyan-Somalis to lie on an airstrip for days, ultimately killing “close to one thousand.”] There are so many historical injustices that were never addressed, and we just moved on. We had a culture of silence. People are speaking out more right now, but in the ’90s it wasn’t so. Some things were always left unsaid.

Guernica: One of my favorite things from the novel is the music. There is so much Lingala. There is Samba Mapangala, and Mbiu teaches Ayosa how to dance chakacha. It’s a really wonderful thing, reading a book, seeing all this music, and thinking, Oh, I know this music, I remember this music from my childhood.

Okwiri: When I was writing the book, I was trying to recreate Nairobi. Mapeli town is a fictional town, but it’s based on something I know so intimately and remember about my childhood. My father listened to a lot of Awilo Longomba and Papa Wemba, and I was trying to recreate this rich textured tapestry, and bring it onto the page. The ’80s in general and early ’90s were the Golden Age of Lingala. And there were all these bands, pushed into exile or escaping political turmoil in Congo, and they moved to Nairobi. So growing up in the ’90s, Nairobi was very vibrant. It felt like the very ground was throbbing. And not just in terms of music, but also in terms of the food and the dialogue, the way people speak, the musicality, the timbre and cadence of their words, things like, “Your mouth is full of mud,” or “I’m the one who’s telling you,” “Bible-red,” and “wallahi.”

Guernica: There is this dirge the people in Mapeli sing: “Luwere Luwere.” I imagine people in this town walking with their hands behind their backs, shaking their heads, and singing, “Luwere Luwere.” Do you think about them in the same way?

Okwiri: No, actually, Luwere Luwere is more like the multiplicity of an acute awareness of death; that it’s a part of life, and it’s something that is sad, but also it’s something that is happy. Luwere Luwere is a dirge that I remember from my childhood. At the few funerals I attended, this song was sung, and it was a very scary song to me when I was growing up. All my feelings about death, all these things that I didn’t understand, all percolated in this one song. So for me, this one song is what death is when I think of it. But to the townspeople, Luwere does not mean the end, but the beginning of something else; that a different kind of life begins at death. The dead are ever present and are still alive among us. And even when we meet the town on Epitaph Day at Mama Chibwire’s Beer Parlor, they are drinking beer in the brew mugs, and they’re really sad, but they’re also really happy to have these memories. And they can’t wait to cross over so that other people can think of them in this way and dance to “It’s Disco Time” by Samba Mapangala.