_What’s revealing about Obama’s art selections for the White House has nothing to do with gender or race. It’s more abstract than that._

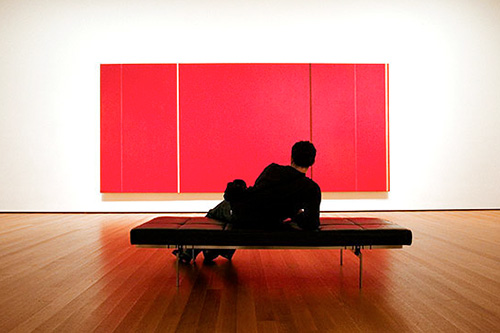

Photo by “Dan Eckstein”:http://www.daneckstein.com

The artists not included in the White House’s four-hundred-and-fifty-piece permanent collection read like a greatest hits list of twentieth-century American art: Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Edward Hopper, Jasper Johns, Willem de Kooning, Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Joan Mitchell, Robert Rauschenberg, Ben Shahn, Andy Warhol. Women and African-American artists are represented by a paltry eleven and five works, respectively (to say nothing of Asians, Hispanics, or other minorities). Instead, the collection comprises some eighteenth- and nineteenth-century works of historical and artistic significance, like Gilbert Stuart’s 1797 portrait of George Washington; mediocre portraits and replicas of more famous depictions of Presidents, First Ladies, and once-iconic personages long lost to history (does the name Fanny Kemble ring a bell?); idealized scenes of leisure; and pastoral landscapes of American splendor, from the Hudson River Valley to the American West.

But President Obama is ready to break with this staid tradition. In June, the White House announced that the President plans to “round out the permanent collection” and “give new voices” to a culturally diverse collection of artists, according to a White House spokeswoman quoted in the _Wall Street Journal_. To that end, President Obama has already borrowed a number of works to get the ball rolling. The media has responded with excessive curiosity regarding his “unusual” choices, in much the way it did following his nomination of Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court.

But the President’s interest in minority and women artists is hardly as iconoclastic as it seems—just as his nomination of Sotomayor, whose politics are relatively centrist, cannot accurately be described as noncomformist. What is revolutionary, however, and what has been overshadowed by the media’s emphasis on identity politics, is Obama’s decision to bring abstract art into the White House—a move he made on his very first day in office, when the National Gallery sent over Ed Ruscha’s painting I Think I’ll, in which the words “Think,” “Wait a Minute,” “Maybe I’ll,” and “On Second Thought” are superimposed on a cloud-like orange, white, and mustard-colored background. Other abstract pieces that the Obamas have borrowed, and that suggest the direction in which the permanent collection may be headed, include Richard Diebenkorn’s Berkeley No. 52 (1955), whose broad swathes of green and lavender suggest a land- or seascape; the lesser-known Alma Thomas’s Watusi (Hard Edge), which shows broken-looking squares framed by broken blue rectangles; and Josef Albers’s Homage to the Square, in which a series of squares nest one inside the other.

As the Cold War gained heat, abstractionism was lumped in with communism.

Diebenkorn and Albers were white males, Thomas an African-American woman. But displaying the works of Diebenkorn and Albers in the White House is just as renegade as displaying Thomas’s. In order to understand why, it’s necessary to take a brief tour of the role that abstract and modern art has played in concert with our national character.

Although modernism saw its U.S. debut in 1913 at New York’s Armory Show, it wasn’t until the forties—when an influx of refugees, artists among them, fled the Second World War for New York—that modernism became an American quandary. As a result of this influx, New York replaced Paris as the so-called capital of the art world, and the movement known as “Abstract Expressionism” took hold. These European transplants—and their American friends—brawled in Greenwich Village public houses (Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline) and summered and caroused in what was then the affordable Hamptons (Pollock and Lee Krasner, Willem and Elaine de Kooning). For inspiration, they looked to their own dreams, fears, and obsessions; myths; African, Native American, and Mexican art; and the works of Freud and Jung. They focused on color as opposed to narrative, politics, or identifiable symbols. In short, the movement and its heroes engendered tremendous artistic and personal swagger of a quintessentially American strain.

But beginning in the late forties, as the Cold War gained heat, abstractionism and abstract expressionism were lumped in, per official U.S. rhetoric, with communism. The story went something like this: abstract art was made by communists or fellow-travelers (given many of the artists’s political sympathies, a claim not entirely without merit); the works made the U.S. look ridiculous, broken, or depraved, thereby weakening it and making it more susceptible to communism; abstractionism drew on European influences, which, as foreign “imports,” threatened U.S. sovereignty.

Together, these three strains of thought colored governmental discourse regarding art, particularly at the legislative and executive levels, during the Cold War. Rep. George Dondero, for instance, declared that “art is considered a weapon of communism, and the Communist doctrinaire names the artist as a soldier of the revolution.” Specifically, he explained, “abstractionism aims to destroy by the creation of brainstorms.” President Truman, less vituperative in his rhetoric, claimed that “any kid can take an egg and a piece of ham and make more understandable pictures.”

To understand abstract art, one is challenged to explore the subjective territory and insights of one’s own mind—an individualistic, peculiarly American, and definitively non-Communist ideal.

But these critiques extended far beyond mere blowsy discourse. They resulted in real consequences, including the cancellation of exhibitions sponsored by the government meant to promote American values overseas during the Cold War. Those shows included Advancing American Art, sponsored by the State Department and intended to tour Latin America and Europe beginning in 1946 and Sport in Art, funded by the United States Information Agency, meant to accompany the Olympic Games in Melbourne and canceled in 1956. Artists featured in those shows included, among others, Ben Shahn, Robert Gwathmey, Lyonel Feininger, Arthur Dove, and Georgia O’Keeffe—artists whose work Congress described as “junk” and “gobbledegook.”

In the meantime, and as the ultimate case of the right hand not knowing what the left hand is doing, the CIA promoted these very same artists abroad. To do so, the CIA had set up dummy foundations—among them the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Farfield Foundation—through which it laundered government money used to sponsor overseas cultural programming promoting American ideals. These included not only art exhibitions but also magazines, symphonies, lecture series, operas, and symposia. Ironically, when it came to art exhibitions, the CIA promoted the very same “gobbledygook” that was the subject of such intense excoriation at home.

In part, the argument goes, cultural elites and members of the CIA alike recognized that abstraction coalesced with Cold War American values. As MoMA director René d’Harnoncourt declared in 1948, at the annual meeting of the American Federation of Artists: “I believe a good name for such a society [as ours] is democracy, and I also believe that modern art in its infinite variety and ceaseless exploration is its foremost symbol.” By extension, d’Harnoncourt and others argued, if artistic censorship is the hallmark of such repressive regimes as Nazism and communism, artistic innovation ought to be the hallmark of our own.

Beginning in the nineteen seventies, so-called revisionist historians including Eva Cockcroft and, later, Serge Guilbaut, suggested that the CIA had promoted abstract expressionism because its leaders recognized that movement’s emphasis on the individual. Indeed, it is true that the artist’s fears, dreams, and desires are of primary importance in abstract expressionism, and that individuality, particularly in the face of communism’s emphasis on the collective, represents the ultimate American ideal. But it seems to me equally significant that abstraction emphasizes not only the artist’s individuality but also the viewer’s. Unlike figurative art—say, John Singer Sargent’s stunning Mosquito Net (ca. 1912), in which a woman, swathed with mosquito netting, reclines in bed, and which was gifted to the White House collection in 1964—paintings by Josef Albers, Alma Thomas, or Richard Diebenkorn do not easily resolve into narrative. Moreover, abstractions with few or no recognizable symbols make it even more difficult for viewers to decipher their meaning. To understand abstract art, then, one is challenged to explore the subjective territory and insights of one’s own mind—an individualistic, peculiarly American, and definitively non-Communist ideal.

By the late nineteen eighties and early nineties, Congress had moved on from its discomfort with abstractionism. Instead, it focused its ire on the National Endowment for the Arts’s support of work whose subject matter it considered objectionable: Robert Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic photographs of men engaged in sadomasochism, for instance, and Andres Serrano’s photo Piss Christ, which shows a crucifix submerged in Serrano’s urine. The problem, so went the argument, was that the government, via grants from the NEA, had paid for these so-called blasphemous works. In response, Congress slashed NEA funding, condemning it to little influence and even lesser relevance. In fact, the organization has yet to recover its peak level of funding ($176 million) which it received in 1992. (Not even Obama is ready to take on this issue; for his 2010 budget, he asked Congress for $161.3 million, a slight increase over years past). As a result, and in contrast to its activity during the Cold War, during the past twenty years the government has provided significantly less meaningful support, covertly or overtly, for the arts.

But within the greater United States, suspicions surrounding abstractionism didn’t die with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the opening of the East. Instead, the anti-abstractionist sentiment that characterized our executive and legislative branches during the Cold War bled into the American psyche and affected our national reputation: Americans—known as intellectually lazy, simple to a fault—could not abide abstract art: it’s too hard, too confusing, too strange.

The prevalence of that attitude is succinctly demonstrated by Amir Bar-Lev’s 2007 documentary My Kid Could Paint That, which tells the story of four-year-old Binghamton native Marla Olmstead. The fact that Olmstead’s brightly colored abstract oil paintings sold in Anthony Brunelli’s Fine Arts gallery for upwards of twenty-four thousand dollars raises questions about the value of abstract art. If the work can be deftly created by a four-year-old, the logic goes, what good is it anyway? As Michael Kimmelman, art critic for the New York Times, points out in the film, “There’s this large idea out there that abstract art and modern art in general has no standards, no truths. And if a child could do it, it pulls the veil off this con game.”

In a sense, Americans’ suspicions toward abstraction are related to our general devaluation of creative pursuits. According to a 2002 survey, 81 percent of Americans think they have a novel in them—even though we don’t much read, by comparison to other nations. As a result of our democratization of culture, we’ve arrived at the belief that, when it comes to art-making, any one person can do it as well as anybody else—the difference being that most choose not to become painters, writers, photographers, or sculptors. This national mythology, of course, belies the reality that although many are called, few are chosen.

It isn’t easy to purchase works for the White House collection. First, there are the bylaws guiding acquisitions: the works must be older than twenty-five years; traditionally, the artists are no longer alive; and with few exceptions, they must be American. These same stipulations apply to gifts and bequests, which is another way of growing the collection. There is also the labyrinthine acquisitions procedure to consider, which can last for years given that it requires approval from the Committee for the Preservation of the White House.

Making matters even more difficult is the committee’s restricted budget, which makes the proscription against acquiring works by living artists a sort of self-sabotage. In the art market, it’s a given that the value of an artist’s work escalates dramatically following the artist’s death. It is nearly impossible, as a result, for the White House Preservation Committee to purchase works by deceased artists of major significance. Members of the committee are aware of this double-bind; William Kloss, for example, an art historian who has served on the committee since 1990, acknowledged as much after Laura Bush successfully lobbied to accept for the collection a gift of a painting by Andrew Wyeth, who was then still living. “Thank God they did accept it,” Kloss told the Wall Street Journal. “Then he died and they’d never be able to afford it.”

Nevertheless, in spite of the attendant financial and bureaucratic obstacles, major purchases were made during both the Clinton and Bush administrations. Hillary Clinton—for art in the White House has traditionally been handled by the First Lady—arranged the acquisition of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Bear Lake, New Mexico, the first piece by a twentieth-century American woman to enter the collection. She hung it in the Green Room and was criticized for doing so; the work, said critics, was out of step with the room’s traditional décor. In 1996, the Clintons added the first work by a black artist to the collection, Henry Ossawa Tanner’s Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City, purchased for $100,000 from the artist’s grandniece. More recently, in 2007, Laura Bush bought Jacob Lawrence’s 1947 oil painting The Builders, for which the White House Acquisition Trust, a privately funded component of the preservation committee, paid $2.5 million.

Not surprisingly, given the lens through which the media have critiqued President Obama’s choices, the media focused on the painters’ identities, rather than on the art itself, when assessing the selections made by Mrs. Bush and Mrs. Clinton. But O’Keeffe and Lawrence are now very well-known artists in America. Yet, these very selections—billed as groundbreaking at the time of acquisition—turned out not to be so.

Take O’Keeffe. Even when we look at her work on a superficial level, we understand it easily. I say this not to diminish her art, or to suggest that her works do not contain great symbolism. But any person can recognize a skull or flower and leave it at that. Similarly, although Jacob Lawrence’s _The Builders_, which shows black men building a house, can be analyzed to reveal great profundities, it, like so much else in the collection, tells a readily comprehensible story—a story far different from the one told by Howard Chandler Christy’s tart portrait of Grace Coolidge (wife of Calvin) with her dog, Rob Roy, but a story nevertheless.

President Bush, in a detail that seems lifted from a Saturday Night Live skit, decorated the Oval Office with borrowed photorealist paintings of Texas by the painter Tom Lea.

None of these paintings more clearly failed to effect any meaningful change within the White House collection than Tanner’s impressionistic landscape. When it was purchased, Hillary Clinton attempted to sound the bell of history: “It is a deep honor for the president and me to honor Tanner’s contributions to both African-American culture and the cultural life of our nation.” But the painting does not break with the White House collection’s prevailing style, nor does it overtly represent the black experience. Rather, the painting is akin to other sweeping vistas in the collection, and a celebration of an American scene. As David Driskell, an art history professor at the University of Maryland who helped find the painting for the White House, told the New York Times, “I doubt that people going through the Green Room, even if they are told his name, will know that he is African-American.” The piece, so in tune with everything else in the collection, is not salient in any way—which fundamentally undermines the reason it was purchased.

This brings us back to the analogy of the Supreme Court. Although the appointment and affirmation of Sonia Sotomayor appears revolutionary, her relatively centrist politics are not heterodox. Yet in the U.S., we tend to look to the superficial differences instead of to deeper, more meaningful ones. That same attitude underpins affirmative action, which favors minorities regardless of their socioeconomic background—even though the differences between two whites, one working- and the other middle-class, could be far greater than the gaps between middle-class whites and blacks. Indeed, our obsession with superficial differences applies equally to our search for superficial similarities—our religions or the color of our skin—as opposed to a genuine consideration of, and inquiry into, the similarities that lie beneath.

Bush looked to a single representation of things as they are. Obama at least gives the impression of considering a multitude of opinions, which differ depending on who is doing the looking.

As previously mentioned, one way for presidents to circumvent the permanent collection’s rather tortuous acquisitions process is by borrowing art. Because neither money nor objects of value changes hands, it is a far more expedient way to refresh the art on the White House walls. Yet even works on loan to Presidents and First Ladies have tended to hew to the very traditional, and conservative, modes of art of the permanent collection. President Clinton, for example, borrowed a cast of Rodin’s The Thinker, and in the Oval Office he hung Childe Hassam’s The Avenue in the Rain (part of the permanent collection). President Bush, in a detail that seems lifted from a Saturday Night Live skit, decorated the Oval Office with borrowed photorealist paintings of Texas by the painter Tom Lea. “He [Mr. Bush] liked things that reminded him of Texas and said he wanted the Oval Office to look like an optimistic person works there,” Anita McBride, Laura Bush’s former chief of staff, told the Wall Street Journal. Those paintings, with their chilly palette and hyper-realism, strike an almost surrealistic chord, evoking the same sense of stopped time as Dali’s melting clocks.

(The exceptions to these staid loans were Hillary Clinton, who borrowed Willem de Kooning’s Untitled XXXIX, 1983, long since returned to the artist’s private collection, and Laura Bush, who hung a Helen Frankenthaler canvas in her private quarters. Clinton told the New York Times Magazine that she adored the de Kooning but her daring taste seems to have started and ended there; other pieces she borrowed included a bust of Eleanor Roosevelt and a 1920s landscape of Scranton.)

Obama, by contrast, has borrowed the aforementioned works by Diebenkorn, Thomas, and Ruscha, among others (though it is not yet clear what he will install in the Oval Office). It may be somewhat dangerous to extrapolate leadership style from one’s taste in art—it’s an urge that seems similar to the impulse toward autobiographical literary criticism—but I believe the vastly different selections of Presidents Bush and Obama are somewhat revelatory. Like any office-worker faced with the task of decorating her cubicle, the president selects images for his offices to motivate and inspire him, to relieve him from the daily grind. Without putting the presidents on the couch, as it were, it does seem safe to say that as in their leadership, so in their taste in art: Bush looked to a single representation of things as they are; what you see is what you get. Obama at least gives the impression of considering a multitude of opinions, which differ depending on who is doing the looking.

By bringing works by the likes of Diebenkorn, Thomas, and Albers, as well as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Louise Nevelson, into the White House, Obama is symbolically ridding the executive mansion—and, by extension, the U.S. Presidency—of the xenophobia that has informed the American rejection of abstraction. Our national fear of abstract art— “I don’t get it”—and the anger that it can provoke—“You call that art?”—are, at least in large part, vestiges of the anti-foreigner attitudes of the forties and fifties, which informed those fundamentalist congressional objections to abstractionism, and gave rise to such blots on our history as the House Un-American Activities Committee, McCarthyism, and the electrocution of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg.

Obama’s selections also demonstrate that we are smart enough to “get” abstractionism. He’s smarter than we are, and more eloquent—and, as a graduate of Columbia and Harvard Law, as much a member of the Ivy League elite as is President Bush. But President Obama has repeatedly endeavored to make himself, and even his heterogeneity, relatable. A person from a blended family, a background colored by loss, with the problems, struggles, internal conflicts, and flaws familiar to so many other Americans. Perhaps if one ordinary American is willing to take the time to appreciate and understand abstraction, the rest of us may find ourselves inspired to do the same.

**Rachel Somerstein**’s essays and criticism have appeared in ARTnews and Next American City. She recently earned her M.F.A. from New York University and is presently at work on a collection of short fiction. She teaches writing at Lehman College.