When Chris Lockhart and Daniel Mulilo Chama set out to write Walking the Bowl, a deeply reported look at the lives of street children in Zambia’s capital city, Lusaka, they began with what they didn’t know — exactly how many street children there are in the world, for example. If hard numbers were murky (between ten and fifty million), they were also the most common “information” on offer. Reading the plethora of government and advocacy organizations’ reports on street children, Lockhart and Chama write, “sometimes feels like reading a census taker’s description of hell.”

Together with colleagues, they set out to write a different kind of story, one that looked at what was missing from those reports: “the children themselves.” Their research team included five former street children, a journalism student from the University of Zambia, an outreach worker (who had been a street child, too), and an anthropologist. The result of their five years of collective immersion is Walking the Bowl — a propulsive work of narrative nonfiction fiercely anchored in social science, yes, but also a work of intimacy, surprise, and deeply felt humanity.

For The Cutting Room, Guernica’s new column for creative work that helped make a book but didn’t make it in, the authors have shared excerpts from their team members’ journals, or “street notes,” collected over a two-week period in 2016. They have been lightly edited, in a way that does not alter their meaning, for clarity and comprehension outside of their original context and purpose.

— Jina Moore for Guernica

Talking with a 15-year-old girl who lives part time on the streets. In the middle of our conversation, a razor blade falls out of her mouth. She giggles and puts it back in. She keeps it there for protection.

Twenty boys and twenty mangy dogs laying together in a big pile at night in an alleyway. The boys hug the dogs on cold nights to keep warm.

Group of white tourists leaning out of bus to take photos of two street boys fighting. Logo on side of bus says “Classy, custom-made safaris and tours.”

Street term: “Those without lungs.” Street kids who are traumatized for one reason or another and walk around in a catatonic-like state.

Question from a 13-year-old street boy: “Is everything I see about America on TV really true? Is it always so different and obvious and flowing?”

Street kid with burns on his face. Other kids claim he got them when he tried to light a cigarette after sniffing glue and petrol all day. The solvent fumes leaching from his pores caused him to catch on fire. They say it’s a common injury.

Woman places large cast iron cooking pot on her front door stoop after using it to make maize meal. Six street boys immediately converge on it and scoop out the hard, crusted leftovers, making odd humming noises, like honeybees, as they work. It takes less than thirty seconds to clean out the pot. Woman comes out again and says, “It is the easiest way to remove the crust from the sides of the pot.”

Glue sniffers’ rash = rash around the mouth that often extends across the face. In the worst cases, it eats away at the nose.

Midnight. Street boy walking, repeating a single phrase: “I saw her. I saw her. I saw her.”

“They keep telling us they love the poor. But do they know any of our names?” Comment from 14-year-old street boy in Chibolya about Westerners who come to Lusaka to do volunteer work, usually for their churches.

Group of girls who live part-time on the streets roasting grasshoppers over bits of charcoal they scavenged from a nearby waste heap.

12-year-old street boy holds up knife and says, “This is the short form of death.” He kneels down, pats the street, and says, “This is the long form of death.”

Story about a street boy who uses the bathroom in Dan’s office. When Dan went to use it later, he saw two footprints on either side of the toilet seat. The boy had stood on the seat and squatted.

Boy rolling tire down center of street in the central business district. Inside the tire was a stuffed SpongeBob SquarePants. Saw the same boy later that day standing in front of a line of cars at a busy traffic stop, refusing to move, holding the SpongeBob SquarePants in his hand. Reminded of Tank Man, the guy who stood in front of tanks at Tiananmen Square.

At night, if boys run out of glue, they sometimes pry open the gas tank door, remove the gas cap, and take turns sniffing.

13-year-old boy who stayed permanently at city dump. Never wore clothes; naked all the time. His feet were so hardened and callused that he walked across broken glass without noticing.

Question posed to a group of a dozen or so street boys: what age do you expect to live to? Average age of responses: twenty. Follow up question: what do you want to be when you grow up? Most common answers in order: doctor, lawyer, social worker, engineer.

At night, older boys sometimes pour the contents of their glue bottles on the feet of younger boys who are sleeping and then light them on fire. Can be random. Older boy’s explanation: “Just to show them who is who and what is what.”

Busy intersection downtown Lusaka. All the covers on the nearby sewer/drainage holes missing. A kid was in each hole — only their heads were showing. Just heads popping out of the earth. Nobody noticed.

Dan’s story about two boys in his office. One had stationed himself by the light switch and was flicking it on and off. The other boy ran towards the light bulb each time. He was trying to run faster than the light.

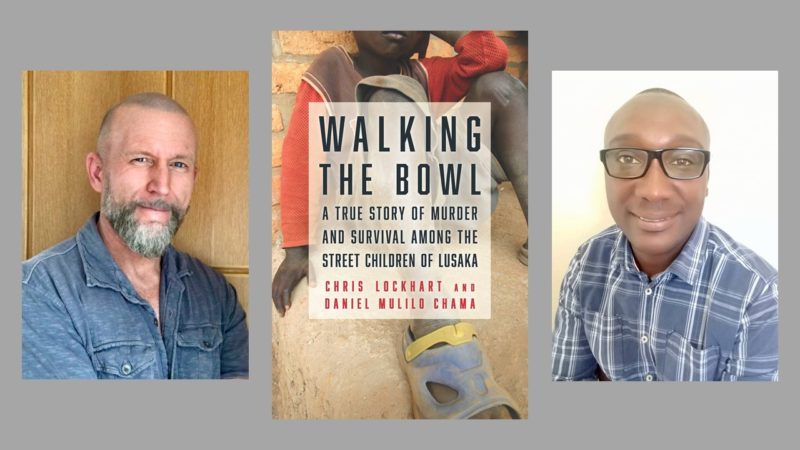

Walking the Bowl: A True Story of Murder and Survival Among the Street Children of Lusaka is out now from Hanover Square Press.