The following is an excerpt from Gå Bara: Min Flykt från Somalia till Sverige (Keep Moving: My Journey from Somalia to Sweden), by Abdi Elmi and Linn Bursell (Stockholm, Ordfront, 2016), here translated for the first time. The excerpt details Elmi’s childhood and youth in Somalia, followed by his journey from Sudan to Libya through the Sahara.

I grew up in Mogadishu, a name that makes everyone think of war. Who was at war at any one time varied, but their identities never made much difference to those of us who lived there. War was ordinary, habitual; we’d grown familiar with it. We handled it as best we could. When we were seven or eight years old, we played warlords with sticks as weapons. When I was thirteen, my classmates died as soldiers. We grew up to the sounds of gunshots. At night, in the dark, my siblings and I would lie in bed, listening, guessing which kinds of guns were firing. AK-47, BM-21, antitank rifle. Each had its own sound: the AK-47 a hard patter, the antitank rifle a heavy, lonely bang. The BM 21 multiple rockets, which could shatter a whole house. Sometimes the gunshot sounds were distant; sometimes they were close. We were always afraid.

I have never experienced peace in my homeland. Somalia is a wonderful place: Mogadishu is sunshine and turquoise seas and beautiful white beaches. Tourists should be flooding in. All my life I have wished, intensely, to see what Somalia would be like without war.

I was born in 1994. Three years earlier, in 1991, president Siad Barre was removed from power. To the rest of the world, he is known as a ruthless dictator. He assumed power in 1969 through a military coup, then ruled the country with an iron fist. But during the chaos that was Mogadishu in the 1990s, he became a symbol for a time when there was security and order, when the roads were passable, when hospitals and schools functioned. All the old folks around me liked to reminisce about Barre’s era. Things were bad, back then. But now they were worse.

The Somalia in which I was born was run by warlords. The warlords were like gangsters; they had weapons; they drank and did drugs. They shot people whenever they wanted to; they raped and beat up innocent people; women could barely leave the house. Then there were the clan conflicts. In the rest of Somalia, the clans are scattered across a wide territory. In Mogadishu, the clans live side by side; we are neighbors, which caused bloody conflicts every day. There was no government or president in control of the country; there was no justice system to speak of. Outside forces made a few attempts to establish order. In 2000, a provisional government was created, supported by the UN. But Ethiopia did not like this, so they intervened and helped foment a Somali alliance opposed to the government. To avoid further conflict, a new government was created, this time composed of different clan leaders from all over Somalia. It was called a transitional government. From the start they had great difficulty cooperating; too many conflicts already existed between them. The clans blamed all the problems in the country on each other. And the warlords only got stronger.

This was my world growing up. It was what it was. My family was very important to me: my father, my mother and my younger siblings Abdifatah, Hamdi, Samsam and Adbikah. I remember a constant stress. We were always on our guard. My mother and father were afraid; they didn’t want me to go far. My friends and I tried to find pockets of calm, places where we could play and live. The sea was close, and we played on the beach, too small for anyone to bother us. There was war all around us, but we were just kids: we played anyway. We played at being adults, at being warlords; we swam, we watched football, we joked and we laughed. We went to the movies. We sat in the dark as movie after movie rolled up on screen; you only had to pay once, then you could watch as many movies as you liked. Our favorites were the Bollywood movies from India, dubbed with Somali voices; they were long, action-packed and the hero was always strong. When we grow up, we will be just like them, we would whisper to each other. We, too, will be heroes one day.

The warlords sat there in the dark as well. I suppose they thought they were heroes already. At the movies, though, they didn’t care about us, and we weren’t afraid of them. Everyone just watched the screen. There, a drama was being played out that everyone could understand. The reality that existed outside the movie theater was much less easy to grasp.

For my parents, whether my siblings and I would go to school or not was never a question. Father was a teacher himself and believed passionately in education. But most of the children who lived on our street did not go to school. They were impressed by the fact that I did. Often, when they had questions, I was the one they would ask.

“Abdi, you go to school, you should know this!” They would say.

Sometimes conflicts between the warlords’ militias ranged close to our school. Then it closed; it could stay closed for days.

My father said that the violence was stealing our dreams from us. Our future. A child who only sees and thinks about violence will end up as a soldier. He didn’t want me to be a soldier. Neither for the warlords nor, later, for the government or Al-Shabaab. But I was never to speak of such things outside of our own house.

Then they will shoot me, he said.

That was enough. I kept quiet. My father trusted me, and I trusted my father.

In 2006, Mogadishu was taken over by a group called the Islamic Court Union. The ICU was an alliance of all the independent courts in the country, and it was trying to create order out of all the chaos. All of a sudden, you could put the warlords on trial when they killed someone. The ICU quickly took over all of the warlords’ territories; the warlords weren’t used to resistance. Some fled the country; others abruptly became devout, started growing out their beards, asking for forgiveness for their sins and attending the mosque. Soon the ICU controlled all of Mogadishu.

It felt unreal. People weren’t being robbed as soon as they left their homes. We could go outside at night, everyone could: women, men, children. We dared dream about the future: new dreams, new hope. I had never experienced anything like it. A new era was starting in Somalia, a good era. We were going to create a better country. I was full of hope. Nothing could go wrong.

The same year the ICU took control of Mogadishu, Ethiopia sent in thousands of soldiers to drive the ICU out of the city, together with the UN-backed transitional government. Most people in Mogadishu didn’t want to give in; they didn’t want a return to the chaos of the past. The ICU gave people weapons and told them they were going to be heroes. They told us we had permission from Allah to go to war. That if we killed Ethiopian soldiers it was not haram – a sin – as killing otherwise is. It was self-defense. That’s what they said. Suddenly, there were lots of young volunteer soldiers. And the period of calm was gone.

The war intensified. It had been easy for the ICU to get rid of the unorganized warlords, but the Ethiopian army was a different story. Soldiers died; young boys died, anyone who came within the line of fire died. The euphoric feeling of change and hope went up in smoke. It was horrible. There were food shortages; health care was even worse than it had been before.

My school changed. All the teachers talked about now was the war, how important it was for all of us to volunteer, so that we would win. They told us that we had to defend our country. “Are you ready?” They asked. “Are you ready to be heroes?”

Many of my classmates got caught up in the excitement; they, too, wanted to be admired; they wanted to be great men. I wasn’t really sure what I thought. I agreed with what my teachers said about the Ethiopian forces; I had seen for myself how they shot people in the streets, how they bombed whole neighborhoods with MB-21s. I thought they should leave us alone, and give the ICU a chance. But I wasn’t sure I wanted to go out and wage war. Not really. I was only fourteen.

Shortly thereafter, the fighting became so intense the school had to close; all the students moved back home. But things were hardly better there. I was no longer a child, or at least no longer regarded as one. I was fourteen, which meant I was no longer safe. Al Shabaab had begun as just a small youth group within the ICU but grown stronger. Then there was the government, the Ethiopians – it was as if there were thousands of eyes, all around me, watching my every movement. One day I was on my way to the store when a few government soldiers approached me. They aimed their rifles straight at me, into my face. This wasn’t unusual; I’d had guns aimed at me for as long as I could remember, so I wasn’t afraid, just tired and annoyed. The government soldiers didn’t inspire as much respect as Al-Shabaab. Their uniforms were worn, and for the most part, they were old and untrained.

“What do you want?” I asked.

“Where do you live?”

“Over there,” I said, and pointed at our house.

“We know who you are; we know you’re in Al-Shabaab,” they said.

“No, I’m not, I’m not in anything. I’m just me,” I said.

They patted me down, trying to find a gun, weapons. They searched my pockets, too, found the money I was supposed to have gone shopping for. About half a dollar that my father had given me. The man who found the money grinned and put it in his pocket.

“Are you taking my money? If you’re government, aren’t you supposed to protect me? Instead of steal from me?”

I was so tired of them that I didn’t have the energy to be afraid. They didn’t do anything; they didn’t help anyone. They just ruined things. How was anyone supposed to have faith in the government? How were young people supposed to believe they were a better alternative to Al-Shabaab?

“Oh, get on with you,” they said, finally. Apparently they’d decided I wasn’t dangerous.

I started walking. Then I heard gunshots. I turned around quickly, just for a second. But it was enough: it was Al-Shabaab, attacking the government soldiers. I ran, as fast as I could. Was it because they’d seen what had happened? Were these old friends of mine?

I couldn’t live like this. I had to choose. Except every choice was impossible. The next day Al-Shabaab soldiers approached me and asked me why I hadn’t joined up yet.

“My mother is sick,” I lied. “I have to take care of her.”

They shook their heads, thought I was weak, a coward. This didn’t bother me, but I knew they would just keep asking. And I didn’t know what to do to get them to leave me alone.

The Ethiopian forces fired rockets and grenades at us all the time. Airplanes attacked us at night. The front line of the war was right in the middle of the city. We slept outside, in the yard in front of our house so it wouldn’t collapse on top of us if it got hit. I was terrified all the time. What if we died? My siblings were so small. Samsam cried quietly. We huddled together, listening. A rocket could go off at any moment.

One night, a house in our neighborhood was hit by rockets. A family lived there, with two children. We knew them. My mother went there the next day, searching for the family in the ruins. She was weeping when she came home. She told us there were no bodies left to take care of. They’d scattered into too many different pieces, spread out, torn apart. She said it was impossible to see who the broken limbs had belonged to. My throat closed, from grief and fear. I knew it could just as easily have been us.

There were dead bodies everywhere, all across the city. No one dared take care of them; there were snipers hidden on all the roofs; they shot at anyone who tried. Bodies remained in the streets for a long time.

Our fears for the future grew and grew. Things only seemed to be getting worse. From Siad Barre to the warlords to this? Why did change never lead to things getting better? We had longed for peace. Now the city reeked of dead bodies.

It is impossible to describe. My city, my homeland. The only place I had ever known.

We couldn’t stay. My father didn’t want to leave; he was scared of what would happen to our house; what if it was gone when we came back? But my mother told him the house didn’t matter. We mattered; our souls mattered. What good was a house if we weren’t alive?

So we left. We knew we could borrow a house right outside a village called Lafoole. There are only a few houses there; the people are very poor. But it was more peaceful there, and my uncle sent us meat and milk so we’d manage for a while. I tried to find the calm I always used to feel when I was in the countryside, visiting my uncle. But it wouldn’t come. I felt hunted. Every time I saw a car approach the village my heart started hammering.

My father didn’t think I could stay in Lafoole. It was a temporary solution only. Not even the countryside was safe anytmore. This wasn’t a war we could hide from.

And Al-Shabaab soldiers came, even to Lafoole. They knew me from school; they talked to me, told me I had to choose a side. They were everywhere now. My father didn’t know what to do to protect me. He was too old for them to care about, my siblings were too young. But me? The soldiers knew me. They’d managed to get my classmates to join; they wanted to get me too. They wouldn’t give up. If I wasn’t with them, I was against them.

My father did not want a letter from Al-Shabaab, saying congratulations, your son has entered Paradise. He wanted his son to live. He realized there were no more options left to us.

And so, one night, my mother and father decided that I was going to Europe. Europe was safe. There were no wars in Europe. That was about all we knew, but it was enough. I could have a real life in Europe; I could go to school, be a child, become an adult – an adult with options. My father talked to my uncle and he agreed to help. He sold three camels so I could have money for the trip. My other uncle, who lived in Nairobi, agreed to help with money along the way. After that, there was nothing to do but go. I just decided; I couldn’t think about what I was leaving behind. I was fourteen years old.

When we have been a month in Khartoum the smuggler is finally satisfied that there are enough of us to make the trip worthwhile. He says we will travel in a car called a Land Cruiser. It is fast and can drive through sand; the military uses it. In Somalia we call it an Abdi Bile, after a Somali track star who set the world record at 1500 meters in the 1987 World Cup. The smuggler says that in the Land Cruiser it will take us four days to get through the Sahara. That sounds good; it sounds as if we will make it. Four days isn’t impossible.

I borrow a telephone and call my father’s shop in Lafoole. Oday-Bile, a friend of my father’s, answers. My father is not there. Oday-Bile asks how I’m doing. I say I am mostly all right, that I’ll be okay. But I am about to travel through the Sahara. I ask him to tell my father that I will call in four days. After I arrive. If I don’t call, then I probably didn’t make it.

Oday-Bile promises to do so. “Abdi,” he says, “your father is very worried about you. He thinks about you all the time.”

“I think about him as well,” I say. “Tell him I will be all right, tell him I trust the people who are driving us and that I will be traveling in a Land Cruiser. It will be fine. It won’t take that much time.”

I hang up, the longing to hear my father’s voice so strong that I feel as if I’m breaking apart, but I don’t know if I could have managed to sound calm and confident if I’d talked to him.

We can’t drive at night, because then the airplanes from the Sudanese army can see us. As soon as they see car-lights they send the military into the desert. We can only travel during the day. At night, the cars stop and people gather in small groups and make food.

The first night I can’t sleep. You’re supposed to lie directly on the sand, but it’s cold at night in the desert. I lie down and stare at the sky. Above are thousands of stars and sometimes an airplane. Perhaps it’s the army, perhaps it’s tourists going on vacation. They don’t see us, I think. They don’t know we exist. We are completely alone.

I can’t fall asleep. I’m afraid that if I do, the car will leave without me. I have heard that it happens. Many of the others separate themselves from the group, sleep next to a stone or beneath a tree, to get some shade by the time the sun goes up. But this can be dangerous. The smugglers only yell for us once. Then they leave. Later we will all start to sleep in front of the cars so that we wake up if they start.

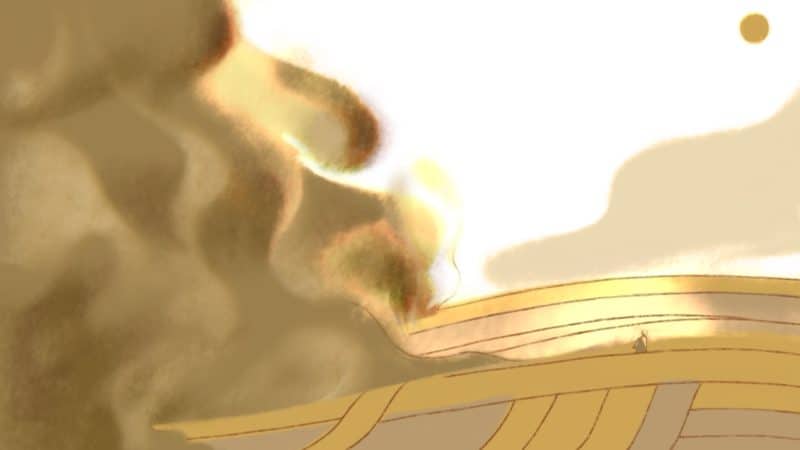

The desert is frightening. There are no houses. A few solitary trees in the beginning. Then nothing. Only sand. The sand blows around us and sticks in our mouths and throats and eyes. It is difficult to breathe properly. It is very, very warm during the day, over fifty degrees Celcius. We drink a lot of water, you have to in order to make it. Some pour water over their heads to cool down. We think the journey will take four days. The water will only last for four days.

Suddenly a boy falls out of the car, it happens quickly, there’s nothing to hold on to. He falls. We call, tell them to stop. They do, after a while. They are irritated and at first don’t want to turn around, but we say we refuse to go on, we aren’t going to go on, we have to turn around, otherwise the boy is going to die. So they turn around, finally. And we find him. They yell at him, “Why did you fall? Sit still! Sharpen up!” They beat him with a wooden bat. The boy is quiet, takes the beating without attempting to defend himself. At least he seems grateful the car returned. Later he tells me that he jumped. He didn’t go any further into the Sahara. Now he’s in pain because of the beating. Why do they treat us like this, beating us? I don’t understand it.

We travel and travel and only see sand. I have never seen a landscape like this. Now there are no trees at all. The sand dunes are endless. But suddenly we stop.

“Get out of the cars, all of you!” The drivers say.

We don’t understand what is happening but we know we have to obey, so we jump off, landing softly in the burning sand. Everything is quiet for a moment. Then we hear the sound of car motors. Other cars arrive, old worn trucks that can barely get across the sand. They must have waited for us somewhere. The trucks have two floors, rickety benches to sit on. The men who’ve driven us this far slam the car doors shut and leave. They’re going back to Khartoum – I guess to collect the next group of migrants. Now the journey will no longer take four days. We only have food for four days. We only have water for four days. Someone tries to protest but they’re told to shut up.

Now we’re truly terrified – but there are no alternatives. I have no options: I can’t stay here. I can’t refuse. Everyone else is thinking the same thing: we have no options. So we continue. We climb up into the trucks. The smugglers paw at the women, laughing and grabbing them roughly, pinching their thighs. The women try to avoid them, but they also have to get up into the trucks as quickly as possible, avoid angering the smugglers and risk getting left behind. Someone tries to tell the smugglers no, but then one of them raises his gun. A warning.

There is nothing we can say, absolutely nothing. One after another we all get up on the trucks. We try to hold on to each other so we won’t fall off when the trucks start. We sit very close together. I close my eyes and think, soon this will be over, soon I will open my eyes and see a wholly different reality lie before me.

After a few days we are stopped by a militia group in the desert called the Janjaweed. They capture us and demand fifty dollars from each person. Not everyone has the money. They rape several of the women, both those who can pay and those who can’t. To the men, it doesn’t matter. They say they seldom see women in the desert and now they want them. They tell an older woman who cannot pay that they’re going to kill her.

The woman tells them, calmly, “You can’t kill me, only God can kill me. Only God decides over my life.”

They tell her to kneel. She does as they say, again telling them that they cannot kill her.

Then one of them shoots at her. Everyone closes their eyes. The woman screams. But he fired just above her head. A false execution. Then he laughs. “Of course we can kill you,” he says. “We can do whatever we want.”

They use their guns like toys, as if it’s all a joke, and harmless.

We’ve been stingy with the food so that it’s lasted us ten days, but we’ve had to eat most of it during the time they’ve kept us prisoner. They’ve given us nothing to eat or drink.

Then, in the end, they just let us go. When we start driving once again, the food is almost gone.

I sit next to a man called Abderahman. We start to talk; he talks for a long time about his family. For five days he sits in front of me. It is nice, despite all the horror; I feel safe with him. He tells me that he worked in southern Sudan for three years. He sends all his money home to his family in Somalia; all the money they have comes from him. Then he wasn’t allowed to keep his job. That’s why he wants to get to Europe. He wants to get a job. Maybe his family can join him. That’s the dream.

“We have lost our country,” he says. “My family is hungry, that is why I have to travel through the Sahara. Because of the war. It’s like committing suicide, but I do it for them, I have to do it for them. All they have is me.”

He has problems with his heart, too, he says. We are hungry and thirsty. The food is gone and so is the water. Abderahman begins to look tired; he seems sick; he just lies down. When he is awake he begs for water. But there isn’t any. Someone goes up to the drivers and asks for water; they still have water. They take out their guns and shoot at him.

We leave early each morning. I sleep in the car. It is easiest that way; time passes more quickly if you sleep when you can. When I wake up, Abderahman is lying on his side, completely still. On the floor. At first, I think he is just sleeping, but something looks wrong. I wait; he has to sleep; he is so tired. His heart needs rest; it needs to beat long, slow, safe beats. Perhaps he’s dreaming about his family. I refuse to think anything else.

Then another man wakes up. He sees Abderahman. He jumps down and feels for his pulse. A moment passes. He shakes him. Another moment passes. I don’t know how long that moment was.

“How is he?” I yell.

“He’s dead.” The man sits up, looks around; maybe he’s wondering what he should do.

I can’t believe he’s dead. It can’t be true. I jump down as well, continue to shake Abderahman, just like the other man did. I hit him, I yell his name.

“Don’t touch him!” The others yell. “He’s dead!”

“No, we were just talking, he can’t be dead! We talked this morning, he was just as usual.”

I know they are right but I don’t want them to be. They can’t be. Tears come. I pull away from Abderahman’s lifeless body.

I’ll never make it, I think. I will die, just like Abderahman.

“You are too young,” the others say. “You don’t understand this. You shouldn’t be here.”

Someone in the truck shouts that Abderhman is dead, and we stop. The driver says we’ll bury him in the sand. I don’t have the strength to help; I am too hungry and dehydrated. But some of the others do. He is buried. Then we go on. We keep driving. I want to scream, but I can’t. I will never forget Abderahman.

People have saved sugar. This makes them fight.

“Why are you fighting about sugar?” I ask. One man says sugar makes it easier. Easier to endure. He is large and looks strong, he forces the others to give him sugar, beats one man, takes it. The other man simply crumples. People don’t have any resistance left. The strong man dies during the last days of the journey. Some say it’s because he beat others, because he stole from them. That it’s a punishment. I don’t know.

It is like prison: the strong take from the weak. Everyone is desperate. But it isn’t certain that the strong are the ones who’ll survive. People wonder how I survive, why I am not screaming after water. But there is nothing strange about this. I cannot scream. There is sand in my throat.

I just sit.

One man even checks to see if I’ve been keeping extra water to myself. But I haven’t. I just sit. I live. It is the only thing my body can do. Survive.

I don’t know why it works.

Perhaps it just isn’t my time.

Others die, and all the time more of them. An old woman in our truck has diabetes. You can’t live without water if you have diabetes. We have talked a lot, she and I, about the situation in Somalia, about how it used to be and how it is now. Like all old Somali I’ve ever met, she misses the reign of Siad Barre. The woman could be my grandmother. Kind. Considerate. Determined. She is thirsty; she has to have water. She becomes more and more desperate. She screams after water, pulls at the clothes of those who sit next to her, screaming, begging for them to give her water. But no one can. Because no one has any.

I sit closer to her, to comfort her, though I cannot do anything. I just hold her hand. She moves uneasily, she wants to jump out of the car, says she wants to die. But we hold on to her; tell her we don’t want her to die alone. Eventually we don’t have the strength. We are too tired. But by then, she is too tired to jump. She is motionless, now, but screams hoarsely for her son; she thinks her son is there, in the truck; she calls for him, tells him to come and help her. Save her. She screams and screams. I can’t stand it. We tell her, “Please, mother, your son is not here.”

But she doesn’t understand. She screams until she is too exhausted to scream any more. She whispers his name.

Then she dies. There in the truck. Everyone starts staring at each other, thinking, who is next? Who will go crazy now? Start screaming. Who will die?

I cannot bury her either. I sit in the car and just watch what happens. I used to watch horror movies back in Somalia; this is like a horror movie. My brain is telling me it is a horror movie. Because it doesn’t resemble reality. People screaming after water, people just staring at their feet, people dying.

I sit, motionless. I don’t speak. I know we all die one day, but it wasn’t supposed to be now. I want to live. I want to see my family again. I want to have a life. How can you die when you’re just fourteen? I am a child, I am actually just a child, even if it was a long time since I saw myself as one. I don’t get to decide when I die, I know that and it’s okay; everyone has to die some time, just not when you’re young.

A man sits down in front of me. He’s maybe thirty-five years old. I haven’t spoken to him before.

He says, “You don’t look well. You’re exhausted and sick.”

I nod. I am.

“Do you have any family?”

I tell him my family is in Somalia and my uncle is in Nairobi.

He nods. “You are probably going to die soon,” he says. “I can tell. Write down the telephone number of your father and uncle and I will call them and tell them, when I arrive.”

This makes me furious. I am so tired, but rage arrives like a wave. I can’t scream. I hiss the words. “How can you say that? How do you know when I am going to die? It could just as well be you. And I have already spoken to my father. He will know there are problems, because I haven’t arrived yet. He will find out anyway. Don’t tell me I’m going to die. It could just as well be you.”

He dies a few days later, that man. A few days after we spoke. People look at me, whispering, murmuring. About what I said, that it could just as well be he who died. Some of them become afraid of me, start to keep away. They think I set the devil on him. I don’t have the strength to care. I’m too tired to do anything.

It is so horribly hot. It feels as if the sun is closer here than it is anywhere else on earth. It is maybe 60 degrees Celcius. When the wind blows in the Sahara, everything fills with sand; it sand forces itself inside you. Sand in your mouth, throat and eyes. When you’ve slept and try to wake up, you can’t open your eyes. People who live in the Sahara wear cloth wrapped around their heads, with just a thin slit for their eyes. The drivers wear something like this as well. But not us. We didn’t know.

More people die. I have seen dead bodies before but this is the first time I am watching people die in front of me. From thirst. They scream. I can’t do anything. They are buried beside the road. Some people drink their own piss. I understand them but refuse to do it myself. One of them dies instantly, the other a bit later. I’d spoken to them earlier. Two boys and a girl. We tell the drivers that they have to help us, otherwise every single one of us will die.

They realize it’s true and start to give us a bit of foul each night, maybe a half deciliter. We stand in a long winding queue while they point their weapons at us. It is the only food or drink we receive for an entire day.

Four people die. Then seven more. No one has the strength to bury them anymore. We just throw the bodies out of the truck.

We have been thirty days in the desert. I cannot breathe. I cannot speak. There is sand everywhere, in my throat, ears, eyes, mouth. It is so hot. No roof on the trucks. No one speaks. We are all going to die. There is no hope.

We don’t know we are almost at the border. The drivers don’t tell us.

Suddenly we see Land Cruisers. It’s the Libyan army. Armies terrify us; we know we’re traveling illegally and that they’ll put us in prison, but when the cars stop we still throw ourselves onto the ground and run, stumble, stagger towards them.

They shoot in the air, shouting, “Get your hands up!”

We obey. Stop and lift our hands.

We know things are not good in Libya. We’ve heard that, anyway. People in Sudan told us – about how they despise black people here, that all the smugglers are thieves. We know this. And still, we did not know enough. We thought, this is the military. They will put us in a refugee camp. I was happy to see them. I thought, now, at least, I will live a little bit longer.

“Get in line,” they say. They don’t look mean, right now they almost look kind. We’re at the border. It isn’t marked with a fence, but there are two mountains, and there it is.

I get in line, but I almost can’t; I can’t wait. Finally, I get there; I get water. I drink. Many can’t. Instead, they receive a liquid substitute. If they can pay, that is. The soldiers are beginning to understand what a poor state we’re in. They’re going to drive the ones who have money to a village nearby. For this, they want fifty dollars. They yell orders at us. Get in line, get in the car!

It is what is normal for this journey: to be ordered about, beaten. I feel it less each time it happens.

There is a man named Nour in the line. He has traveled from the Congo. Nour means light in Arabic. The soldiers mock him – because his name is Nour, even though his skin is dark. He says nothing. He looks down. He wants water.

We can’t say anything about what they do to us. We can’t do anything. You’re quiet. You obey. You pay them what they want. If you can. The ones who can’t are left behind. I don’t know what happens to them afterwards, but I have heard things. That they leave you behind to die. Women pay with sex. Stay with me for a week and you’ll have paid it off, the smugglers say. But there is no guarantee that this is what will happen. They end up having to stay with that man for the rest of their lives. I’ve also heard they sell people’s organs. They give you water and food. You can pay later, they say – when no one who has made it through the Sahara says no to food and water. You can’t. Then they take you away. Take out a kidney. Cut you up like an animal.

I don’t know. There are no words for it. Words disappear here.