On April 14, 1965, Sol LeWitt wrote Eva Hesse what must have been the most encouraging letter in the history of the arts. Hesse, the minimalist sculptor and WWII refugee, needed help. After having fled her birthplace of Hamburg, Germany, when she was two years old, she returned to the country when her husband, a roguish artist named Tom Doyle, was offered a free studio in Kettwig-am-Ruhr. But most of her relatives there had been murdered in the camps, and now that she was back, she couldn’t work with the ghosts. Though she would later make history with her latex installations and her absurd “nothing” sculptures, all she could do was draw a little, paint a little. Most of her product looked bizarre and pointless. In a panic, she sent off a long missive to LeWitt, a future father of conceptualism and one of her closest friends: “[My drawings are] clear but crazy like machines…. it is weird they become real nonsense…. Everything for me personally is glossed with anxiety…. how do you believe in something deeply? How is it one can pinpoint beliefs into a singular purpose?”

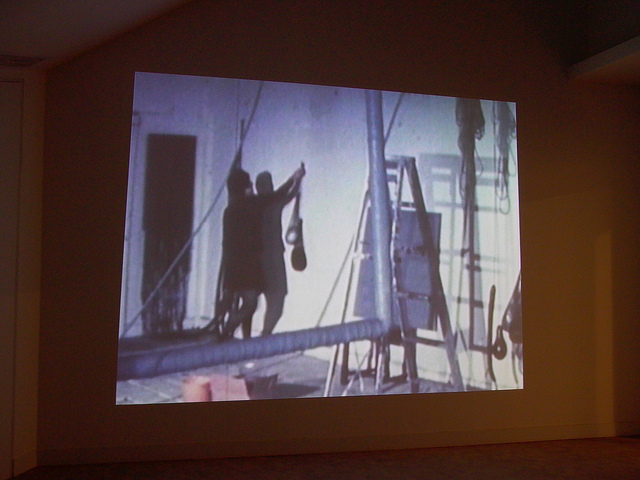

Film director Marcie Begleiter tells the story of LeWitt’s response in the documentary Eva Hesse, which opened on April 27th. In this, Begleiter’s first film, we see images of a misty-eyed LeWitt, baby-faced with black horn-rimmed glasses and a receding hairline. He was probably already in love with Hesse by then, she struggling away in her German studio, he making art out of cubes in far-off New York. Hesse was a stunner—dark haired, black-eyed, passionate, and a burgeoning genius. LeWitt rushed to her aid with an exclamation-scored letter offering intensely helpful if counterintuitive advice. In Eva Hesse, we hear his words in a voice-over performed by Selma Blair:

“If you fear, make it work for you—draw and paint your fear and anxiety. And stop worrying about big, deep things such as ‘to decide on a purpose and way of life.’…. You must practice being stupid, dumb, unthinking, empty. Then you will be able to DO!…. Try to do some BAD work. The worst you can think of and see what happens but mainly relax and let everything go to hell. You are not responsible for the world—you are only responsible for your work, so do it.”

Hesse took this advice. She dove down deep into her malaise and came up with imagery no one had ever seen, let alone conceived of. The year 1965 saw an explosion of her famous reliefs, made out of Masonite, cord, and paint. These would flower into her sculptures: the loopy priapic forms of Ingeminate (1965), the rope-tangles of Ennead (1966), and the stark, latex rectangles that comprise Augment (1968). During this period Hesse would also leave Doyle and struggle to make it as a female minimalist whose work struck strange notes next to the elegant lines of Donald Judd and the ethereal fluorescents of Dan Flavin.

Try to do some BAD work. The worst you can think of. LeWitt’s counsel offers a cantankerous alternative to one of the supposed canons of modern creative production: in 1983, the Irish playwright and poet Samuel Beckett wrote Worstward Ho!, a typically baffling masterpiece. The novella showcases a genderless figure who rails about death and despair. Most people only know of its widely touted saying: “All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. / Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Since Worstward Ho!’s publication, ‘fail better’ has grown into a ukase for the creative class. In 2007, the novelist Zadie Smith wrote an essay titled ‘Fail Better,’ where she describes literary production as a glorious car accident: “The literature we love amounts to the fractured shards of an attempt, not the monument of fulfillment. The art is in the attempt.” In 2006, the choreographer Nichole Canuso danced in frantic leaps around precipitously stacked wooden blocks while performing her own ‘Fail Better’ at the Philadelphia Live Arts Festival. In 2014 the Harvard Business School published Anjali Sastry and Kara Penn’s Fail Better: Design Smart Mistakes and Succeed Sooner, a tome designed to teach “change agents” how to “create the conditions, culture, and habits to systematically, ruthlessly, and quickly figure out what works.” And in season one, episode one of the popular television series Criminal Minds, the protagonist Jason Gideon, a criminal profiler, tells his sidekick Morgan that they need to “Try Again. Fail Again. Fail Better,” while investigating a crazy kidnaper of four women in Seattle.

‘Fail Better’ has thus transcended Beckett’s original intention, and now it supposedly helps us write novels, dance, be ruthless change agents, and save women from extinction.

‘Failing Better’ is a thing. Never mind that Smith, Canuso, the Harvard Business School, and Criminal Minds have misinterpreted Samuel Beckett: In Westword Ho! Beckett didn’t envisage a self-help couplet for poets and Silicon Valley titans. When Beckett’s protagonist wails, “Try again. Fail again. Fail better”, he or she means that your life really does amount to a failure, but you should just be tough about it and suck it up. ‘Fail Better’ has thus transcended Beckett’s original intention, and now it supposedly helps us write novels, dance, be ruthless change agents, and save women from extinction. Our contemporary interpretation of the saying pushes us to keep trying and improving. Failure, in this calculus (except for, perhaps, that of Smith), is just a speedbump on the road to triumph. A person who fails better uses the lessons from the last disaster to build a better victory next time instead of diving down the rabbit hole of their catastrophe only to get yet more entangled and lost.

But in 1965, Eva Hesse did precisely the latter, and failed worse. She followed her friend LeWitt’s recommendation, fell down the hole, and so became one of the best artists in the world.

Hesse’s masterpieces make ‘failing worse’ seem like a tactic that we, too, should try. The only problem with failing worse is the reasonable terror that it might inspire. After all, ‘failing worse,’ is un-American, since capitalism requires achievement through striving for the best, and those who strive for the worst are typically branded as outcasts. Also, perhaps you have already ‘failed worse’—say, as a painter, by painting colorful hens on linen for three years, a project that you stubbornly regard as subversively feminist but that has botched your chances at a gallery, and now you have 168 chicken paintings in your garage and no money but a huge fund of bewilderment. Or maybe you have ‘failed worse’ as an unemployed female actor in Los Angeles, and hope that a quarter-century-long paucity of jobs will be resolved in your now-advancing middle age by a multiplicity of well-deserved mother/witch/bag lady star turns, only to discover that Nicole Kidman is getting all of the crone roles.

[LeWitt] prioritizes the idea of being not only empty, but also a dummy—a fool whose inner void is not immediately filled by virtue. LeWitt thought that greatness could arrive from a state of stupidity itself.

But Sol LeWitt described a practice more enriching than just willfully making work that no one will ever want when he exhorted Eva Hesse to be stupid, dumb, unthinking, empty. He was not thinking about a vastness of fowl portraits or an insane faith in The Artist’s Way when he encouraged her to do BAD work. LeWitt instead conjured a form of consciousness reminiscent of beginner’s mind, which is a concept developed by Zen Buddhists. In the classic text Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Shunryu Suzuki describes the state as “empty, free of the habits of the expert, ready to accept, to doubt, and open to all the possibilities.” LeWitt’s iteration proves related, yet distinct: he prioritizes the idea of being not only empty, but also a dummy—a fool whose inner void is not immediately filled by virtue. LeWitt thought that greatness could arrive from a state of stupidity itself. He wanted Hesse to be a fool so that she would discern in that foolishness something new, and with that newness do the bad work that creates a different way of seeing the world.

LeWitt probably also hoped that in this dumb enlightenment, Hesse would see that she was in love with him. That didn’t happen, though.

Failing worse may be a move that some people are too scared to try because they are worried that by failing worse they will fail permanently. Nevertheless, Hesse’s act of living out LeWitt’s guidance shows us how taking the frightening risk of failing worse can sometimes create greater Eurekas than those of the chipper can-doism that is the current trend.

In 1965, Hesse fought off ennui and depression because of Doyle’s philandering. “My concentrative powers are near to naught,” she wrote in her diary on March 8th. “I feel wrong, confused, troubled. But T.D. is not. It’s impossible for me to accept. Why if I was so unhappy with him, do I want him now back.” In November, she submitted to the wrongness, the confusion, and the trouble that pushed her to make crappy drawings: “Compulsive obsession. Obsession—in groove, cannot get out, thoughts only there and work. That is all.”

That month she made a very important piece, Ingeminate. Here was the fruit of the bad work. Instead of Judd’s glossy boxes or the ascendant, aggressive hilarities of Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein’s Pop Art, Hesse made a little pair of connected sausages out of blown up balloons covered in papier-mâché, enamel paint, and obsessively coiled cotton cord. She stuck a surgical hose to the ends of the sausages, so they looked like the phallic handles of a jumping rope. Last, she painted the whole thing black.

Ingeminate is weird. It’s two crazy wieners strangled by cord and leashed by the surgical hose, which dangles and loops messily. In Eva Hesse, Begleiter shows images of the work against white space, and they strike the viewer as a bizarre little fetish. With her dumb and stupid mind, Hesse initiated a sculpture that would later lead to other “repetitive” works, such as Unfinished, Untitled, or Not Yet (1966), which she made out of nine identical lacquered weights each held in a black net bag, and 1967’s Addendum, fashioned out of nine small globes affixed with long strands of rubber tubing and embedded in a wood panel in a straight line. Ingeminate also presaged the ambitious Accretion (1968), made of fifty tall fiberglass tubes propped up on a wall, and Contingent (1968-1969), created out of nine latex-and-cheesecloth banners. Like Ingeminate, these later sculptures are duplicates, and also echo the body: they look like testes, or breasts, or a crowd of people, or people who are vanishing. The fury of Ingeminate has disappeared in her later constructions, but the fetish quality and the physicality remain.

In addition to inspiring a unique oeuvre, Ingeminate also looked forward to what would be known as “Anti-Form” art—art that took its cues from materials rather than venerated the ability of the artist to impose order on them—as well as much of feminist art, with its focus on the flesh and the forbidden.

Hesse may not have been able to make her greatest sculptures if she hadn’t let everything go to hell. It’s in the precise way that she went to hell that can offer a different model of creation than the ‘fail better’ mantra that encourages everybody to stoically do their BEST work. If Hesse had tried to fail better, she might have grappled with what was “good”—Juddian boxes, Warholian kitsch—and tried to improve upon those models with the scraps of whatever looked best from her prior, unhappy experiments. ‘Failing better’ today forms part of the success cult, where failure has nothing to do with the sick and battered part of your life, but is only a stepping stone to glorious achievement. “[T]here’s scope for your mistakes to be smarter,” Sastry and Penn write in their book. “To make something excellent happen, there’s work, more work, and then still more work. If you’re fortunate, only some of it is inefficient.”

Hesse stared straight at what was worst in her life—Nazis and Tom Doyle—and didn’t try to hop over it as if it were a steeplechase.

Failing worse is not just “work, more work, and then still more [efficient] work.” It’s not even Smith’s ‘attempt’. It’s private, psychological, damaged, and inspired. Hesse stared straight at what was worst in her life—Nazis and Tom Doyle—and didn’t try to hop over it as if it were a steeplechase. She studied what those catastrophes had made her: obsessive, sick, and enraged. She wrote in her diary about her febrile mind. She made strange drawings about her feelings. And by wrestling with her demons and domestic problems, she found herself for a while in a place where nothing made sense. How do you believe in something deeply? It’s only after scraping the bottom of her failures and her emptiness that she found the materials for her art.

Hesse is not the only visionary who allowed herself to travel into the dark. Melvil Dewey’s childhood obsession with the number ten spurred him to invent the Dewey Decimal System. Estee Lauder’s fixation on looking at and touching women’s faces led to her building a cosmetics empire. Neither of them could have achieved so much without letting themselves be empty except for stupid ideas, at first. Today, Elon Musk probably represents the epitome of failing worse: though in public he speaks of hating his many fiascos, his often ruinous ventures depend on his idiotic ability to hurtle toward ever bigger catastrophes, from electric car fires to the explosion of his SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. His failures get worse before they get better.

The same is true of Hesse. By sticking with her ‘dumb’ despair and the fantasies it spawned, she touched the hot little button of creation. Was she crazy? With Ingeminate she raged against her husband and other, more deadly sources of male power. She yoked phalluses, turning them into useless nunchucks. She mashed up some papier-mâché. She OCD’d by winding the cotton cord around and around. The process must have been scary, and it could have all ended in the garbage, along with her peace of mind. But by failing worse, and shaping the bad out of balloons and rubber tubing, she found a new art form that no one had ever hazarded before.