By Zimiri Yaseen

Brought to you by the Guernica/PEN Flash Series

my father never spoke.

a stroke had left him speechless before my birth. it is not right to say he never did anything, but he never did any thing people do on purpose to live.

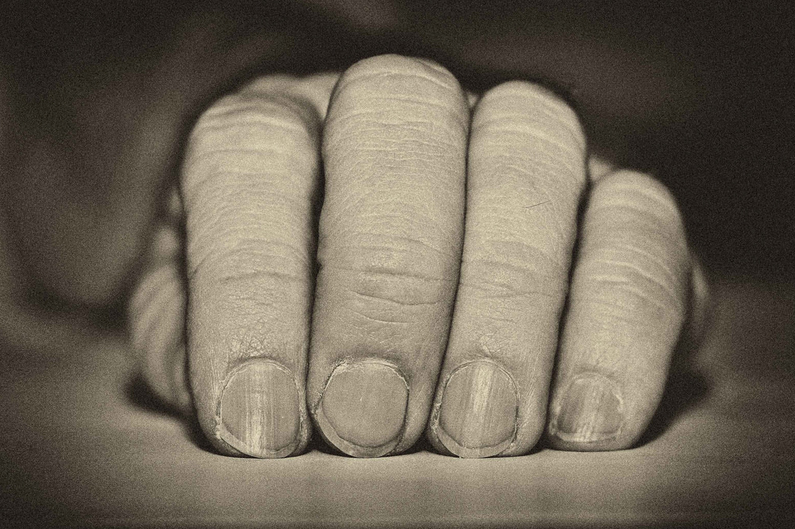

when the hand was opened i had succeeded. when the hand was closed i would begin again.

she told me that at one i reached out and struck his closed right hand with my fat unsteady palm, and like a giant clam taking a deep sea breath, i imagine, his fingers slowly unfurled. then i would slap at his dry palm and the fingers would close, slowly. we played this game for hours when i was learning how to stand. closed. opened. when the hand was opened i had succeeded. when the hand was closed i would begin again.

she said that by the time i could walk he had taught me even and odd numbers. first 2 to open and 1 to close, then 4 to open but 3 to close, then 2 or 4 & 1 or 3, and so on, until i began to feel the intricate mechanism of my puzzle box father extending deep into the night sky inside us.

my first memories of my father were modular arithmetic and the theory of prime numbers.

each interaction only showed its result as a blur of probability.

after school i ran riot with my friends. we ran and made loud sounds and broke small things. we were like the atoms in a bomb, colliding, combining, and releasing sound and fury. i could not tell my father about this for 2 years. in a group of 6 we were smaller groups forming and dissolving. even in pairs each one of us could perform 4 crude kinds of action, or we could form threesomes and foursomes, and because these were but the crudest descriptions, each interaction only showed its result as a blur of probability. besides, we were children, and changing week by week if not day by day.

he was too, but racing like a second hand i could not perceive his minute hand motion. she was an hour hand. to speak with her he did not use the soft machine he’d built for me. they would look at each other. i could not understand it.

there was the equation, and the proof, and there was a little machine we could build and imagine it repeating itself on and on very fast to converge on the smooth truth of an equation.

in high school we got computers and i began to build my father inside of one. it would output 0 when his hand was closed and _ when it would be open. when i told them, they looked at me and i noticed their eyes were more wet than regular eyes. i could see parts of my father were shrinking, like his arms and the sides of his head. the top parts were shrinking, and sagging into his middle, and his bottom parts had begun to swell too.

he didn’t have to say much anymore. he could imply. there was the equation, and the proof, and there was a little machine we could build and imagine it repeating itself on and on very fast to converge on the smooth truth of an equation. a little machine could do that. a big machine could make a little machine. we could build a night sky.

computers have more memory now, and i am still building him. but i am almost finished.

Zimri Yaseen was born in Boston in 1977, but now lives in New York in 2014. In between he has lived in other cities and countries, but not too many. He started writing this story down on an airplane. He would like to thank Di and his family for inspiring it.