As far as I’m concerned, this story about the disappeared schoolteacher is hiding another one, and we’ve got to go back a long way, really far back, to understand it. I’m ready to accompany the child on this road because I know there aren’t many people who can tell her anything about it. I, Nono, say you mustn’t let things get lost; you mustn’t sweep away the old memories, even if they’re a bit dusty. From where I sit, my friends, I’m really in a prime position—on high, if you know what I mean. What disappears in the passage of time, what we usually have trouble discerning, that’s what I see clearly.

I see everything: the family’s intrigues, the events, tragedies, and shake-ups that have taken place in this country. I see it all, understand what I see, and maybe can even foresee a few things. So, yes, the child needs to hear what I have to say, and despite everything else I have to do, I’m ready to give her all the time she needs.

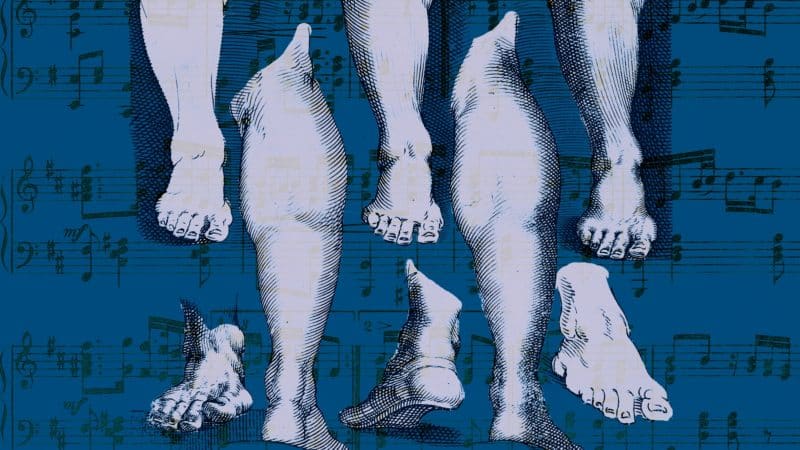

I get the feeling you’re surprised by what I’ve said. But just because I’m dead doesn’t mean I don’t have things to do. For instance, I’m having a really hard time finding a part of my body they forgot to put in the coffin—my leg, if you want to know. This probably sounds like a crazy story, but it’s true. One night I went to bed in my little house, so very tiny that you have to ask how it’s even possible to lose a dead lady’s leg in it… But let me start at the beginning or we’ll all get lost.

Like every night for the more than forty years I’d been living in that house, I fell asleep on my back. I wanted to let my old bones relax a little, stretch out, because all day long I’d been bent over double just to finish the simplest task; it took me forever to walk two feet, grabbing at all the walls I could hold on to. All this to say that, in the evening, my body was tired. So, I got positioned on my back, took hold of my old Bible with the black cover—the same one since… Lord, I don’t know since when—and kissed the Lord’s words before reciting a Hail Mary and Psalm 22, “The Lord is my shepherd.” When I say that one out loud, I feel like I’m being rocked, rocked gently in enormous arms. Once my psalm was over, I must have fallen asleep, because the next day they found me dead, my body already stiff and an arm folded under my head. I didn’t feel a thing coming on.

With time, patience, and a little vinegar, the Tordoncan son from the funeral home finally managed to straighten out my arm. (He’s a real sweetie, but you have to wonder what he’s doing taking care of dead bodies when he should be out finding a pretty, young, and living girl to undress!) A good thing, too, because thanks to that I’ve been able to keep my arm, even though it’s weirdly separated from my shoulder and my body looks kind of crooked. Who knows what happened to my leg, but there wasn’t anything to be done. You see, the knee was bent and hard. They couldn’t get the kink out, so they had to carve up my body or else they wouldn’t have been able to put the lid on the coffin.

They cut off my leg, and since then I can’t find it. Imagine going through something like that! I don’t know why they didn’t just bury the leg with me. But other than that, they took real good care. You can’t say the contrary. I can still smell the scent of basil on my body from the embalming. They plugged the holes up with wax, clove, and candle droppings. Can’t complain about any of that, but my poor leg, someone forgot to slip it into the coffin. And how am I supposed to dance the quadrille with only one leg?

Dancing the quadrille is my greatest passion. You should have seen me dance with that old Gaëtan. Well, I mean, he got old, but when we were young we danced the quadrille until we were nearly dead on our feet, even if there was never, ever the slightest thing between us—other than those square-dance balls and listening to the caller cry out: “Ladies and gentlemen, time to dance the first figure, le Pantalon. Gentlemen, choose your ladies! Are you listening to me? Second figure: gentlemen, to your ladies. Time for l’été. Figure eights if you please…”

Wherever I am, between heaven and earth, I always hear the sounds of a quadrille. It’s with me wherever I go. As soon as I hear the first measures, I try to gather up my skirts, straighten my back, and stop thinking about my missing leg. But what can I do? How can I stand? I don’t dance anymore; I can’t give myself over body and soul (what’s left, anyway) to the music.

What I ought to do now is devote myself to what was always forbidden to me as a woman: playing the accordion for the quadrille. I’m pretty good at it; I used to play when my buddy Étienne lent me his instrument. He’d even boast: “Ou ka jwé bien tou bònman!” Yes, indeed, you really can play!

But nothing would convince him to let me accompany the other musicians. I had the right to dance, but not to enter the men’s world.

Oh well. I loved how that quadrille jumped! Does it still swing like it used to? It’s the accordion and the triangle that made it happen. Those instruments are alert and fluid, like a long ribbon gracefully unwinding. And I loved, too, how elegantly people dressed at those balls. Back then we wore our very best clothes. You really felt like a lady, so you could hold your head high.

I hope we have those balls in the Lord’s paradise and that we’re not just going to spend our time praying! Oh, if that music exists in paradise you can be sure I’ll scrounge up some angel who’ll ditch his wings in a corner to greet me like a queen—unless, of course, I run into that old Gaëtan. I so loved dancing with him!

You know, the quadrille is a perfect example of a group of people living in harmony. We would say, “One for all and all for one.” You could always count on the friends you had from the quadrille society.

I really hope I can find that atmosphere in heaven. That and the rest of my body! If we must be resurrected, I hope the Lord’s angels won’t have to look for pieces of us in every corner of the world. I’d like to believe that, up there, He at least keeps track of all of us lost at sea, all those slaves whose numbers have never really been released—thousands or millions of them. I also pray that He knows where to find all those pieces of the dead that’ve been lost. If He wants to give life again to everyone who’s lived on Earth, He’d better put his shoulder to the grindstone in order to find them all, to put them all back together again.

It’s up to Him to guarantee equal treatment at the resurrection, and to make sure that nobody will be afraid to present himself because he’s missing an eye, a head, a leg, or something else!

In the meantime, since I have no idea what the Lord wants or doesn’t want to busy Himself with, I’ve accepted the job of looking for that leg myself, and I can tell you it’s not easy given all the gussying up that’s happening in this city. Our narrow streets are being turned into broad avenues that’ll completely destroy some of the old neighborhoods, and they’re replacing our run-down cottages with tall apartment buildings. Where will we put our chickens and our pigs, our rabbits and our guinea fowl? On the balcony?

Even my little cabin is about to be razed, so I’ve picked up the pace of my investigation. I look under the furniture they kept from when I lived there; again and again I grope under the bed. My word! It’s unbelievable how much dust accumulates under the bed of the newlyweds who moved into my place.

I’m trying not to think badly of them because both of them work, poor souls. They don’t have children yet—thankfully, or else I might have to put up with their screaming offspring—but even so, they have no rest.

Their weeks are dreadful. I hear them talk, and they’re saving in order to build their own little place on some land the man’s father owns in Boisripeaux, in the countryside near Abymes—the next town over. They need money, and both of them go from one job to another, without even a minute to relax, except on Sundays, but then they have to go to church and visit their old father so he doesn’t change his mind about the land. It’s a fine little property with woods that are plunked down on the surrounding plain. Kind of like the statue of a bride on a wedding cake. They really want that bit of land; they’re dreaming of the countryside, of calm, of a big cement house, solid enough to protect them against the fierce hurricane winds. Dust bunnies under the bed are the least of their worries.

But during the day, when they’re gone, I lift up the mattress and go through the closets. They wonder sometimes about the small changes I make in their house without meaning to.

I hear them argue, but I make sure not to intervene. Anyway, what could I do? Every day I swear to be more careful, but as I was never very organized while alive and on earth, I really don’t think that after my death I’m going to learn to pay attention to exactly how far the bed is from the closet.

Most of the time, when they come back from work, night’s already fallen. The bats have started to circle overhead, and the trees have closed up their arms and become immobile, like they’re sleeping. It’s so dark in the streets that even when you open your eyes wide, as if you’re about to cry, you stay suspended in a kind of vast nothingness, wondering where looking stops.

*

Excerpt from the novel The Restless, to be released by Feminist Press in January 2018.