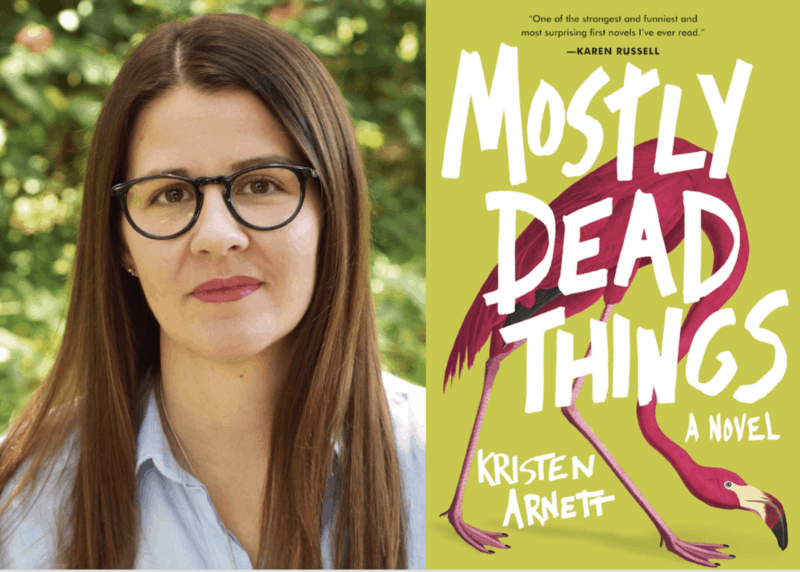

After considering a scenic walk in Leu Gardens, but conceding to the Florida heat—a sultry eighty degrees by 10:00 a.m.—I asked Kristen Arnett, author of Mostly Dead Things to meet at East End Market, a mixed-use foodie venue more reminiscent of a hipster Smorgasburg than an everyman’s EPCOT. Iced lattes are five bucks, the scent of yeasty artisanal bread pads the air, and a robust chef rubs down an impressive hunk of meat. As we look for a seat, Arnett runs into Emily, the market’s manager, and her best friend from elementary school. The spot is all Brooklyn cool, but here, Arnett has unimpeachable local cred. In the first line of Arnett’s bio, she states she’s a queer fiction writer—this authenticity and ownership of place shines through in her debut novel. For her, “Florida Man” is no running joke; he’s the next-door neighbor she understands in all his complexity.

Next February, Arnett will participate in Winter with the Writers. The beloved, month-long literary extravaganza hosted by Rollins College is a Central Florida highlight featuring celebrated authors and National Book Award finalists. The college is also Arnett’s alma mater (where she was a librarian I currently teach creative writing). As a student, Arnett was selected for one of the program’s coveted internships, an opportunity that marked the beginning of her journey as a “real writer.” The invitation is an honor Arnett deserves, but as we talk about imposter syndrome, opportunity, and craft, I find myself excited for the energy and writing wisdom she’ll bring to students hoping to emulate her remarkable trajectory.

Arnett’s laugh is like an exclamation mark, a frequently deployed surprise punctuation that makes an interviewer work to make her laugh even more. Even though she’d long published nonfiction, I first heard of Arnett around the launch of her first book, a collection of short stories titled Felt in the Jaw published by indie Split Lip Press. That reading was held at an area 7-Eleven, an Orlando event noted in the New York Times. Arnett has managed the enviable, sticking to her roots while going places.

—Victoria Brown for Guernica

Guernica: In our preamble to this interview, you mentioned that for the longest time you didn’t think of yourself as a “real writer.” Your second book is about to drop. When did you transition to acknowledging yourself as one?

Kristen Arnett: I still have trouble thinking of myself as a real writer! I’d always written, but just for myself. I always felt compelled to write, but I never showed it to anyone or thought about my writing as something to share. Even at Rollins, I was an English major but I didn’t take a single creative writing class. Eventually, I found out about the internships available for Winter with the Writers, and [program director] Carol Frost selected me to participate.

Guernica: Who were the visiting authors that year?

Kristen Arnett: Chimamanda Adichie, Ilya Kaminsky, Carl Hiassen. Amazing lineup. That was the first time I opened my work up to scrutiny, my first workshop experience. That was the first time I thought maybe this, my writing, is something other people want to see. It was kind of life-changing for me. After that experience, and while I was in Library school, I applied for and got a Lambda fellowship. I kept applying to workshops, and my work was accepted.

Guernica: You majored in English. Why didn’t you ever take a writing class?

Kristen Arnett: This sounds crazy now, but I didn’t want to take up space from someone who was a real writer who wanted to be doing creative writing. I got my degree in English while working as a librarian. I was in charge of Interlibrary loans. I spent my time in the basement. I was a scholarship Holt student [Rollins’ affordable, mostly-evening courses, commuter-student path to its liberal arts degree]. I talked to people in the English department about writing and heard in them a level of confidence I didn’t feel in my own work. I felt like an imposter. I knew the word “writer,” but I never applied it to myself.

Guernica: When you tell me that you’ve always written, I hear that someone must have read to you, given you an early love of words and stories.

Kristen Arnett: My mother did, all through my childhood. She read to me until we got to the point where the books I was interested in were not books she considered appropriate. I grew up in a strict Southern Baptist family, and there’s a long list of prohibited books, exactly the ones I wanted to read. I had to read them in secret.

Guernica: What inspired this book?

Kristen Arnett: I spent time at the Kenyon Writers’ Workshop working on a short story about a brother and sister who wanted to taxidermy a neighbor’s goat. When the story was done, I realized I was still very invested in these characters. I wanted to keep thinking about them; know more about their lives and where they lived and their family dynamic. It was the first time I had ever thought longer outside of a short story than the original dynamic. So I scrapped that story and decided to look more broadly at this concept. That’s what birthed the book!

Guernica: Tell me about your writing practice.

Kristen Arnett: It is a practice. At first I wrote short stories. Those come out of inspiration or an image or an idea and I could get a draft done pretty quickly, like in a day, and then work to edit it. I made a commitment when I decided to write a novel, and I would say I wrote it almost like a short story. I set a daily word count and decided to write forward, to not go back more than a paragraph the following day to maintain forward momentum. I wrote a thousand words a day from Monday to Friday.

Guernica: How long did it take to finish the first draft?

Kristen Arnett: I started in June 2015 and was done by November. I had a lot of pages, about 100,000 messy words, but it was done, and with a competed draft, I could start turning it into something. That was another long process, but essentially I had the shape of the novel finished in six months.

Guernica: What about themes? Were you, especially during the editing process, honing specific through lines?

Kristen Arnett: I don’t think I thought about themes specifically as I worked—that is not how I write necessarily—but I was thinking about the body and the interior. What it means to try and understand the physicality of things versus what it is like to try and know the interior, the spiritual part of the person. It is so hard to know anything about ourselves. It was interesting to try and write a character who wants to control the entire narrative of not only her own life, but also the lives of the people closest to her.

Guernica: The novel is quite funny. Are you consciously a funny writer?

Kristen Arnett: I do love comedy! I love for people to laugh and have a good time. I think I am not ever really considering that in my fiction, per se, but I am thinking about it dynamically in my life. I think there is really not room for pain without pleasure. There’s no room for the ugly without the beautiful. So there’s no room for the serious without the absurd; and I am all about the absurd, sincerely—always thinking about the dumbest, silliest way to think about anything. If that filters into my writing, I am happy for it. I think almost anything can be funny There is so much humor to be found in everything

Guernica: There’s the humor and then there’s the sex in the novel, which is seamless. I’m trying not to say “queer sex,” but there’s something to the gay relationships that undergirds my question. The characters’ relationships are wonderfully complicated for sure, but the sex scenes in particular are not awkward or instructional or immature. As a reader, I loved that lack of hesitation.

Kristen Arnett: It’s what I was going for. Sometimes you want to read about fucking, you know? Lots of people, other queer people especially, want coming-out stories, and at a certain point in my life I wanted those kinds of stories as well, but that’s not what I want to write, not in this book. I wanted to capture the complications of a family’s dynamic, and how queerness functions within the family, but Jessa [the protagonist] is sure of her queer identity.

Guernica: How did Jessa reveal herself to you—is her voice singular, composite?

Kristen Arnett: I think I found her because her voice was so strident. She is such a compelling character, for sure, but she is always such a loud control freak. That is funny to me. I loved thinking about this woman who would not allow anything to affect her. She is so serious about controlling not only her emotions but also her memories and also the actions and feelings and thoughts of the people around her. What a giant personality! It’s difficult to look away from someone who so aggressively wants to be in charge, and that is Jessa.

Guernica: How is it for you, to be queer in Central Florida? I’m asking this one for my tween children who, having lived in Brooklyn for ten years, have a much more fluid idea of gender identity and for my local Rollins students who come from similarly religious backgrounds and are negotiating real tension in their families over their non-conforming sexuality. Is there hope here, or do they have to wait until they’re older when “it gets better” to live the way they want to if they choose to remain? Have you thought about leaving?

Kristen Arnett: I have a wonderful community, friends who I can rely on. Orlando has a thriving queer community and I am lucky to be a part of that world. I don’t want to leave. This is my home and the writing I do is grounded in Florida. Where would I even want to go?

Guernica: You’ve written many essays, especially from the perspective of your librarian experience. Tell me more about writing fiction as opposed to writing nonfiction.

Kristen Arnett: Writing fiction for me is very different from writing an essay. When I write nonfiction, I usually have a burning question or an idea that I can’t get out of my head. I think about it and write it in a way that’s very piecemeal. Those pieces are moveable, like little puzzle pieces I am trying to fit together. I am interrogating questions in order to find larger questions. When I write fiction, it starts with an image. Something specific. I sit inside of it and let it figure itself out. I never have an outline. I love to be surprised by what the characters might say or do. It is always a beautiful thing, to uncover what fiction might bring me. Like a special present.

Guernica: And fiction here brought you the special present of taxidermy. Did you go to a, what is it? A shop?

Kristen Arnett: Learning about taxidermy really satisfied the librarian in me. I read lots of books and articles and you’d be surprised at how many taxidermy videos are uploaded to YouTube. There’s so much information to be had from lurking in online forums and chat groups. Lots of guys talking about what kind of blade they use, about paring back skin. I’m interested in the body and in the gross. And I did find out about the fragility of peacocks. You can basically scare a peacock into a heart attack.

Guernica: Have you heard from PETA?

Kristen Arnett: (Laughter). You’re the third person to ask me that. It’s so funny. I didn’t think about PETA at all when I was writing the book, but now maybe I’m worried.