This interview is a part of “Memory Loss,” a series co-published with Urban Omnibus.

Nostrand, Bergen, Stuyvesant: Many of New York City’s streets and neighborhoods are named after families who owned or traded slaves. For a number of New Yorkers, this fact is unsurprising. Slavery was a source of colossal wealth for the city, fueling the construction of both local infrastructure and the Southern plantations from which its businesses extracted huge profits. In 1730, 42 percent of families in New York City owned at least one person; many slaves were bought and sold at a market located on what is presently known as Wall Street. Still, the origin of the city’s street names elicits disbelief in others. Some are haunted by the question: In 2021, why are slavers still dignified with toponyms?

Streets names are an inescapable part of navigating city life, embedded into the addresses of our homes, schools, and workplaces. It is near impossible to give directions in Brooklyn, for example, without invoking the name of a historic local slaver. The family of nineteenth-century congressman Teunis G. Bergen, for whom Bergen St. is named, owned at least forty-six people in 1810. Nostrand Avenue is named for one of the first Dutch families to colonize Manhattan. The family went on to own approximately forty-three people between 1790 and 1820.

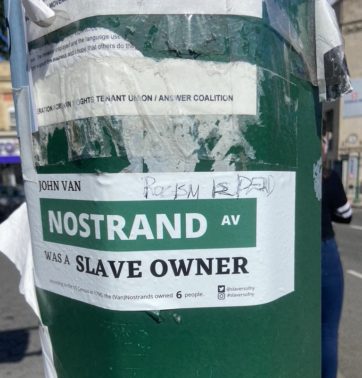

Co-naming a street is an increasingly popular way for communities to interrupt these narratives that privilege slave-owning colonists and wealthy landowners. But the process can often a take up to a year, and is at the discretion of community boards, whose procedures vary across the city, and the City Council. Even when passed into local law, the changes are not reflected on the official city map. So activist group Slavers of New York is changing the streetscape by different means: archival research, mapping, and small-scale interventions. Part of their work involves literally contextualizing the city’s street signs with straightforward, uncomfortable notes about the families and individuals for whom they were named. Here the group’s three founders, Elsa Waithe, Maria Robles, and Ada Reso, discuss their mission to place facts in the hands of everyday people, and to bring attention to legacy of slavery encoded in the city’s signs.

—Francesca Johanson

Francesca Johanson: How common is it for a street in New York City to be named for a slave owner or trader?

Elsa Waithe: When I tell people, several times over, that a street—such as Nostrand Avenue or Stuyvesant Street—is named for a slave owner, they’re like, “Oh, really?” or, “Oh, I didn’t realize that was somebody’s name.” We know Columbus, and we know all the presidents. But Nostrand, Stuyvesant, Cortelyou, and Suydam—many people don’t know about their direct involvement with slavery. Place and street names have been so far removed from people.

Maria Robles: There are lots of Jefferson streets and lots of Washingtons. But often a street is named for the person whose land the street happens to run through. Then there are names that aren’t necessarily well known to New Yorkers—names like Totten, which is used quite a bit throughout Staten Island for neighborhoods and streets. That’s just one example. There are a lot of records that show particular individuals who owned slaves.

Francesca Johanson: How did your organization, Slavers of New York, get started?

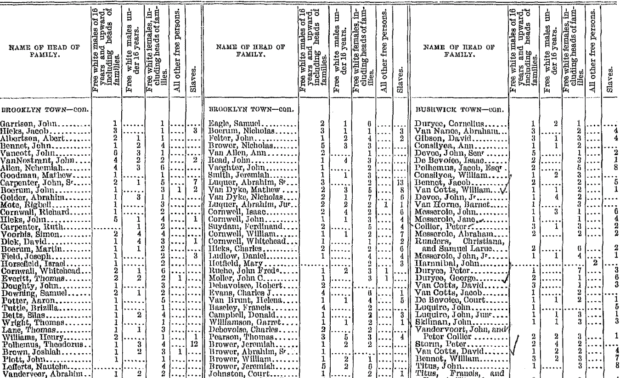

Elsa Waithe: Early in the lockdown, I come across a post on the internet—a scan of some old records with old-timey print. In one column, there were names that I immediately recognized from pretty major streets and neighborhoods in New York. It also had the number of people in the household, the number of children, etcetera. All the way in the last column were how many slaves the person owned. It was a census record. I was like, “Oh, wow. These are pretty prominent streets. I wonder how readily known this information is?” Then I kicked it to the back of my mind.

Fast forward to the murder of George Floyd: I started talking to my partner Ada. During that time, the push to remove a lot of these monuments was global. I was saying, “I wonder how many people know about the streets?” She gets to looking stuff up and getting all this information. I was like, “We should figure out a way to get this in front of people.” We had this idea originally to alter the actual street signs. We felt that might be too big of an idea. So we distilled the idea to stickers.

Ada Reso: Once we started putting them up, that’s how we found Maria. She reached out because she had been working on this too.

Maria Robles: At the beginning of the pandemic, I was also doing my own research. Earlier in the year, there were a lot of conversations around taking down statues in the South. I mean, there are always conversations. But obviously that was amplified in June, after the murder of George Floyd.

I started to think about how slavery happened in the North as well, and how we never really talk or hear about it. Not talking about it is a way of essentially erasing the history. It’s always, “Oh, that happened in the South and it was bad. But we’re liberal and great and so progressive.” And while that might be true in some regards, it’s certainly not true historically. Obviously, the slave trade existed in New York as well. But it isn’t always obvious to many people. I then started thinking about the street names in my neighborhood, Flatbush. Lefferts, as in Prospect Lefferts Gardens, shows up a lot. Who are these places named after? I started researching in Brooklyn, but then expanded to the rest of New York.

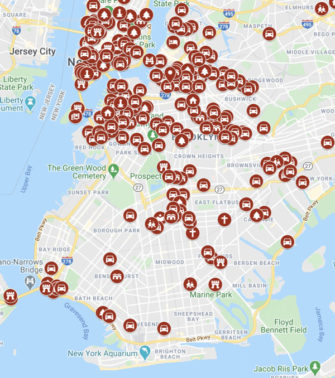

I created a map where I log every landmark—whether a street name, a neighborhood, a statue, or historical site—that was named for someone who is on record as owning slaves. My map became really extensive. It got to the point where now it’s over 500 locations, and over 208 different names. We’re going to publish it soon.

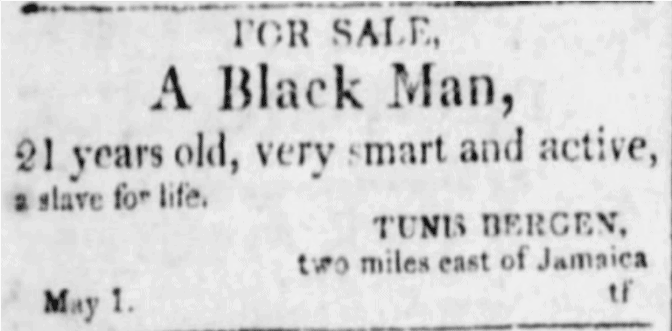

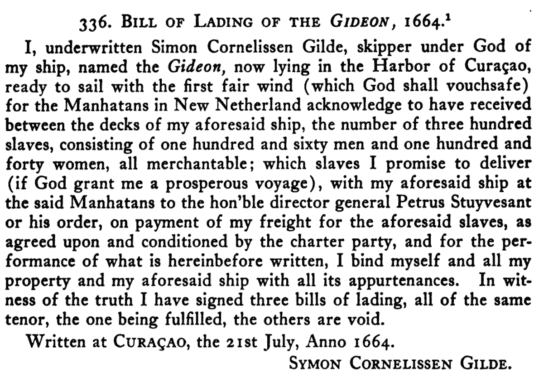

There are a lot of resources online—the New York Slavery Records Index by John Jay College of Criminal Justice, for example. It takes a simple Google search to find, but it also requires some literacy. The database allows you to search slave census records that show you slave ownership within the state of New York. I started reading a lot of historical documents and books, and looking at things online from the New York Historical Society and the Center for Brooklyn History. I also started going through old newspapers, looking at slave bills of sale, runaway slave ads, things like that—all happening within New York.

I started to think: How can I get this information out to people? Maybe a month later, I’m walking around in Crown Heights and I see a sticker on a Nostrand Avenue sign. I was like, OK, I need to get in touch with whoever made this. Then we started working together, around September 2020.

Elsa Waithe: I had no clue what sort of response we would get. But the response was rather immediate; people were interacting with the social media. Maria was the gas—she had already finished the research—and we already had the vehicle, the framework.

Maria Robles: I was thinking about how we reckon with the past with regards to slavery. As a nation, there wasn’t a moral reckoning or awakening that happened, even when slavery was abolished. I’m only one person, but what’s one way that I can start to change things? I felt that education, and access to education, were ways to do it.

It’s one thing to do scrubs of newspapers from the early 1800s, and read census records and historical documents. But looking at newspaper ads, for example, and seeing runaway slave ads, or “for sale” ads in the classifieds alongside livestock, houses and furniture—that was very jarring. Especially seeing names that I was familiar with—names that continue to be attached to addresses throughout New York City.

Francesca Johanson: What has been the most troubling finding?

Elsa Waithe: What I find most offensive, most violent, is that a good number of the streets run through predominantly Black neighborhoods. For me, that feels the most uncomfortable. Many people don’t know who their street or neighborhood is named for, but it’s a constant reminder, often an unconscious one. That’s what bothers me the most. Whether it’s a small street or large, these names have been disconnected from the person.

Francesca Johanson: What’s the ultimate aim of Slavers of New York?

Ada Reso: Mainly, our goal is to just educate people about the legacy of slavery and how it persists in the present day. We don’t advocate for changing the names in any way. We hope that, if people feel so inclined to change names, they create their own groups and engage in political action. I definitely think there should be more context available in public places. When Maria and I went to Stuyvesant Square in Manhattan, a statue of Peter Stuyvesant was there in the middle of the park, glorified, and there’s no information about his slave-owning history.

What’s really interesting is that some of the naming of places for slavers happened more recently than you would imagine. Boerum Hill wasn’t called “Boerum Hill” until 1964 or so, when that name was resurrected as part of the gentrification of Brooklyn. You can see, directly, the entanglement of the history of slavery and gentrification. Bringing this man’s name back into the neighborhood is a symbol of violence. The persistence of these names and links carry this space through history.

Maria Robles: For me, it’s also about education. There are a lot of discussions back and forth about taking down statues and things like that. If you’re taking something down without providing context, that contributes to the erasure of history as well. Another thing—and we’re still kind of working through how to best do this—is that a lot of the census records we’re finding also note names of some of the enslaved people. It might just be the first name; maybe their age, maybe the fact that they were the mother of an enslaved child within that same family. Whatever it might be, it is very basic information. But it’s still giving a name to these enslaved people. We’re thinking about how can we honor them and shift the focus away from amplifying the names of slave owners.

Listen:

Ada Reso describes Bergen Street today, and the family for whom it was named.

Elsa Waithe: I also wanted the goal to be very focused on the information as a way to keep us above any political fray or any back and forth about “do we or don’t we.” Information is neutral, right? This is a fact about this street. If knowing that makes you uncomfortable, live somewhere else. Knowledge is power. But we can’t even begin to discuss the legacy of slavery, what we do going forward, or anything like that, if we don’t know about it. Ada calls this “guerilla education.” (She says she didn’t coin the phrase.) Putting the information where people are. It shouldn’t have to take a Google search.

Personally, I even think: Keep the name, and add to it. Maybe finding a more personal connection is the way to go. The part of Nostrand that I live on now is called James E. Davis Avenue, named for a popular Black police officer and Councilman who was assassinated in 2003 by a political opponent. So there are ways to keep what’s there, provide context, and alternatives.

Ada Reso: I think the process of relearning names is similar to how, in the LGBTQI+ community, language is used to create a more inclusive world—it’s sort of like practicing or respecting people’s pronouns. Paulo Freire, a Brazilian radical educator, talked about how naming the world is having power in the world. I immigrated to New York City with my family in 1992, when I was two years old. When I was at home, it was always about the history of Albania. Going through the American school system, I realized the history of the country is very whitewashed. That was a personal motivating factor: I really wanted to learn more about this so that I’m not living in ignorance in this country that I now inhabit. As a political practice, I wanted to consider how I could shape the world.

Francesca Johanson: So you are against changing names at more formal level?

Elsa Waithe: I think there are two reasons why we haven’t looked into this. Changing a name isn’t necessarily our stated goal, but also, it costs 99 cents to start calling a street something else. We don’t need no act of Congress to collectively come together as a community and be like, “We don’t want to call this Nostrand anymore.”

Maria Robles: We’re hoping to start conversations and provide information around these names. I haven’t looked into details around official name changes. Have there been significant efforts? Maybe. There are still two streets in Brooklyn, on an army base, that are named after Confederate soldiers. There’s a Robert E. Lee Way and a Stonewall Jackson Drive. It is up to the Army to change them, but they don’t want to.

Francesca Johanson: What has been the community’s reaction?

Elsa Waithe: I’ve seen people get angry with Ada. It happened just the other day.

Ada Reso: I was putting up stickers, and this man comes over and reads it and gets very upset. He says, “You’re white, why are you doing this? I don’t want to remember this. I want to forget about this.” I was floored because, up until that point, everyone had been really positive. I tried to respond, “I’m part of a team with people of color.” At the time, I was lost for words. I just had to walk away.

Elsa Waithe: This happened on Nostrand Avenue, coming from a Black man. But then there was my friend, who was followed by a white man on Bergen Street, in a whiter community.

The man said, “Do you live here? Is this your neighborhood?” And she said, “Yeah, I’m going back to my mom’s house.” As she was putting the stickers up, he was trying to interrogate her. He started to pull them off, and followed her down the street for several blocks. He was yelling at her. And that’s a white man. I imagine both people being angry at the fact, but for two separate reasons.

Maria Robles: It’s tricky because, on one hand, we’re just providing facts—we’re not sharing our opinions about the stickers. They are very straightforward. We’re being very careful to only share information for which we have sources that we can point to and say, “Yes, for sure, this person owned slaves.” There are names we’ve looked into that I don’t want to put on the map or make stickers for yet, because I don’t know for sure whether they owned slaves.

That being said—and I know that Ada likely feels the same way—I don’t want to make a decision for Black people about how they should reckon with the history of slavery. They are reminded of it in insidious ways every day. All the time. Non-Black people, especially white people, are going to take in this information in a different way than Black New Yorkers might.

When we’re doing public displays of the information, even though the goal is to provide access, people are not choosing to see it. It’s in your face as you walk down the street, without a warning. So we are really thinking about how do we best share the information in a way that’s accessible, but also mindful of who’s seeing it and how they’re processing it.