Memorials fix in place versions of history. When installed in public, they are invariably political, charged with representing an idea, person, or event to an audience that may or may not be supportive. For years, civic memorials across the country have been flashpoints for larger debates about unequal representation and violence against people of color. This past summer, Confederate and colonialist statues took center stage again as mass protests prompted a reckoning on race, and reinforced the power of memorials to shape national conversations.

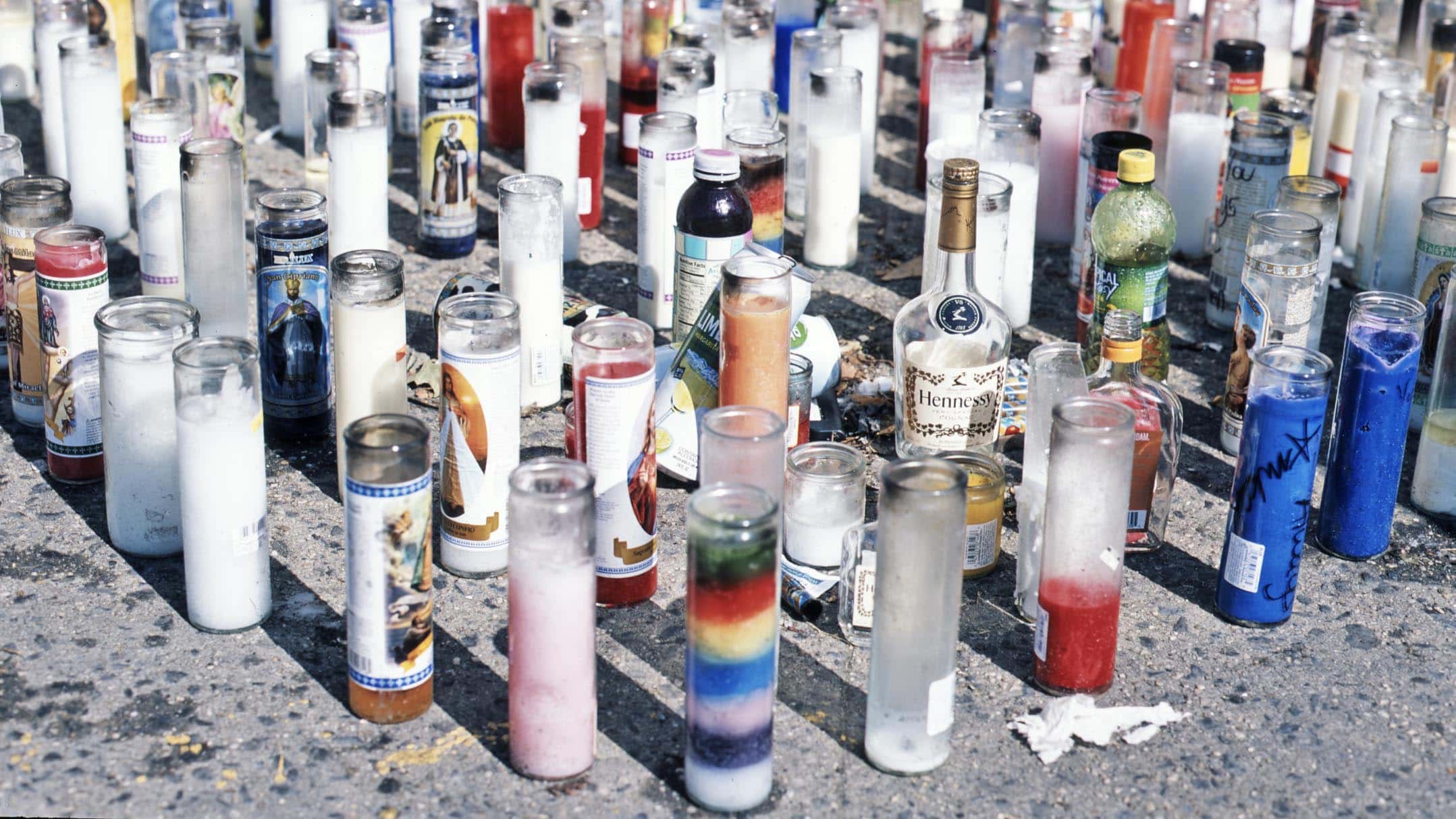

But where does the everyday memorial—the roadside shrine, the informal street name, the commemorative street tree—fit into this scheme? They, too, can share a political tenor, albeit often less spectacular. Some double as public amenities, others redress narratives that elsewhere center whiteness. Makeshift, community-led memorials, such as murals to victims of gun violence, can give a voice to figures many of the bronze busts and plaques across the city were meant to silence. Sites of remembrance that slip under the radar—that refuse classification, permanence, city approval, or a wider audience—expand, and complicate, what we might consider a memorial to be, and to do.

It is with these memorials in mind that we are pleased to announced “Memory Loss,” a mini series, co-published with Urban Omnibus, The Architectural League’s online publication dedicated to observing, understanding, and shaping the city, that explores sites of public and private remembrance in New York. Through interviews, features, and photo-essays, the series investigates the inherent tension of dedicating space to memorials in a city where the subjects and messages communicated may not be widely supported or understood, and how that tension manifests in the built environment. Over the coming months, we will talk to activists who are calling out the names of slave traders on familiar streets; examine a growing catalog of augmented reality monuments to underrepresented histories; and follow nascent efforts to recognize the imminent loss of land to climate change.

–Francesca Johanson

Olivia Schwob: “Mourn and Organize”

Joshua McWhirter, idris brewster, and Glenn Cantave: “A Monumental Shift”

Ada Reso, Maria Robles, and Elsa Eli Waithe: “Mapping the History of Slavery in New York”

Francesca Johanson: “The Roots of Memory”