—for “The Lightening Field,” a land-art work in New Mexico, by sculptor Walter De Maria

The Hot Spring at Lake Tecopa is an impermanent work.

The land is not the setting for the work but a part of the work.

A spring is not a pool but a process.

Heat is the method by which the water pulls us back into our bodies.

The work is an attempt to know that which gives Death Valley its name. Practically speaking this is not possible.

The lava is as important as the water.

The sum of the facts does not constitute the work or determine its esthetics.

No sentence or group of sentences can completely represent The Tecopa Hot Springs.

It is intended that the work be viewed alone, or in the company of a very small number of people.

Proceed along the path to where the water rises from the rock hot and healing. The path is not the route to the work but a part of the work.

Because the body-water relationship is central to the work, experiencing the The Tecopa Hot Springs from inside a bathing suit is of no value. If Victorian sensibilities cannot be overcome, one’s swimsuit should be removed upon submersion, then discarded.

Ideal viewing of the work begins as sunset approaches and continues into nightfall.

The first thing to leave you in the desert is time.

Hot springs can cause abortion and are thought to have served this function in the past.

Lake Tecopa long ago leaked into Death Valley, then Manly Lake.

The temperature of the water varies depending on one’s nearness to a vent, generally cooling as one moves downstream. Vents are often erroneously called “hot spots,” a term which refers to another geological formation entirely.

The mud is good for bites and burns. My mother put it on our dog’s nose when he was bitten there by a rattlesnake.

About a hundred people live in Tecopa. Many of them gather at this natural spring, or up the road at Delight’s, the private baths, or a little more up the road at the public bath. What might that do to a community, to be regularly naked with your neighbors?

How rarely we let pleasure lead the way. Usually our bodies are molded by various structures, tight waistbands, bras, shoes. How often we let some wire dig into us, and for what? If it’s buoyancy you’re after, come to the hot springs, float free, for once, and do it daily. Let your bigness rise in brackish water.

There is no cell service in Tecopa. I have never heard anyone wishing there were. Spaces without cell service are like wildlife refuges for idiosyncratic thought.

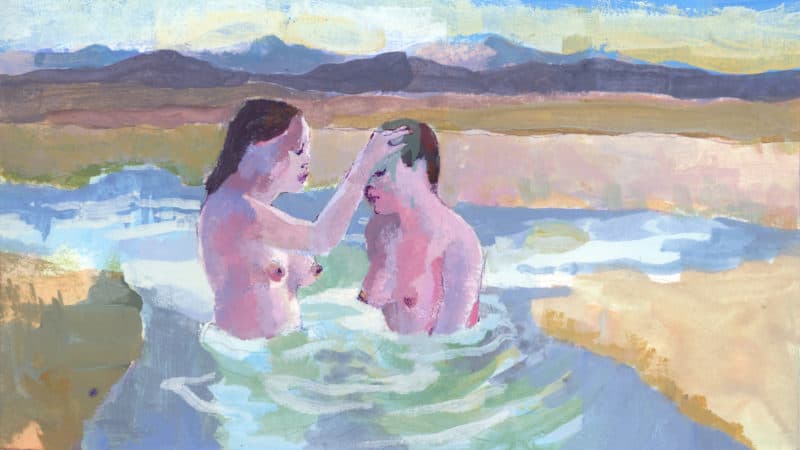

My companion pulls my hand into a hole. She presses my fingers and hers into the silkiest mud there. It frightens me a little. She instructs me to pull up a fistful of green-gray mud and I do. Gently, we smear it on each other’s faces.

As the mud dries, the skin tautens. The sensation in the face will be fairly intense, as it represents the sucking out of any number of invisible venoms.

My father hoped this mud might cure his cancer. He slathered it all over his naked body and sat crosslegged in our garden in Tecopa. He sat naked on a blanket in the sun, hoping.

I’ve lined my windowsills with rocks and thorny plants thirsty for sun. The rocks tolerate handling but the plants would rather be left alone. Periodically I must maneuver them into the kitchen sink to water them, an indignity for all involved.

Floating in a hot spring is a way of knowing a place that escapes the Internet, the park rangers, the anthologists. It is a wordless knowledge, a body logic.

It is essential to become accustomed to drift.

Down the road, the walls of Delight’s are muraled in rich blues and bone whites. Jackrabbits, a girl, the moon painted by a local artist, David Aaron Smith, mainly in the buff.

Naked bodies have stories writ on them in sun and scars.

The public baths beyond Delight’s are bicameral, separated by sex. As a girl I often followed my mother and sister into the women’s side. Clothing was and is not permitted at the baths, so throughout our childhood my sister and I witnessed there a parade of women’s bodies. I loved the shock of them, shock of oldness, fatness, droop, wrinkle, ripple, hair, baldness. I never saw bodies like these anywhere else: marked, resilient, hyper-expressive. These were bodies you wanted to paint, bodies you could read, stories of pain, deformity, malignancy, many operations. The bodies were books about work: child-rearing, housework, yard work, waiting tables, prospecting. Markings of birth about the abdomen, thighs, breasts, the feet deformed by a long story, decades long, in which a girl brings a man a drink.

Yet, and I remember this vividly, each woman at the hot baths seemed impossibly sturdy, an effect perhaps of the refraction of light through the mineral water, or of their big old bushes.

Hot springs are an inoculation against the oppressive beauty standards of patriarchy, its denial of death. In the water we are the opposite of deathless. Naked we float, slow and vulnerable as manatees.

Note the purple mountains, ancient and indifferent.

Bathers should whisper, gossip, stroke each other in secret.

In the winter the steam rising from the springs invites the eye skyward.

The ideal position for experiencing the work is to float on one’s back. Wind ripples through the cattails and tits rise. Nipples harden against the wind. Big black bush surfacing to the stars.

This is the sensation John Muir chased up waterfalls in Yosemite, and which I have begged for, smoking weed in my SUV in the parking lot of Oasis Hot Tub Gardens in a city named for trees. It is, I think, the sensation one hopes to get from a sensory-deprivation tank, or from WeCroak, an app that five times a day reminds you you’re going to die.

Here is the pitch: If you really want to look at death, to know it, to feel in your bones that it comes for you, yes, you, so that you might act accordingly, visit death’s valley then keep going to the next valley over, to Lake Tecopa, which is gone.

Nothingness can be hard to see. It helps to get the right angle, below sea level. From the bottom of an ancient inland sea, nothingness tightens like a mask of mud. A sensation of sublime insignificance, almost orgasmic.

How did you put it, Jesse? If I had a button to make me come I would press it until I died. Sounds pathological. Yet I don’t know a better way to describe making art in the Anthropocene.

It is not uncommon to fear dissolve while floating.

It is not uncommon for lost people to return in dark skies and mineral.

When exiting the work, take care to observe not merely the ecstatic cold, but that this ecstasy lives at the intersection of the wind and your own perfect body. The skin is a part of the work.