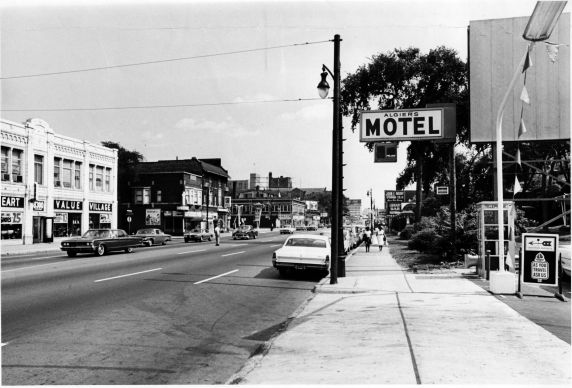

The west side of Woodward Avenue between Melbourne and Mt. Vernon is, upon first glance, pretty unremarkable. There are few obvious signs of the desolation for which Detroit is now nationally famous. Instead, a patch of lawn called Virginia Park, like the neighborhood around it, sits across the street from a thrift store, whose tiled white façade hints at some earlier, grander tenant. Up the street, in impoverished Highland Park, is a derelict factory building that once produced Model Ts; it is decorated with one of those green historical markers that alert the curious passerby that something extraordinary happened there. There is no marker in Virginia Park; perhaps what happened here was rather ordinary. On July 25, 1967, three young black men were killed by Detroit police at the long-demolished Algiers Motel.

The Algiers was the site of the most notorious atrocity of Detroit’s rebellion of July 23-27, 1967—or riot, as many prefer to call it, in a battle over nomenclature whose combatants break down along the same regional, political, and racial divides that have largely persisted through the half-century since the city exploded. All that remains of the old motel are the brick columns at the edge of the park, which now mark an entryway along the wide sidewalks of Detroit’s main street. The columns once framed Virginia Park Avenue, a small winding road that led to the manor homes of the wealthy neighborhood behind the Algiers; both the motel and the road were demolished in the late 1970s to make way for the park.

On July 25, a Tuesday, three Detroit Police officers—David Senak, Ronald August, and Robert Paille—were were called to the motel after reports of “sniper fire” coming from one of its rooms. “Snipers” were the bogeymen of the 1967 revolt, a police- and media-fuelled phantasm of Black Panthers and Viet Cong guerillas lurking in the shadows. No weapon, only a track racing starter’s pistol, was ever found at the Algiers.

Inside the hotel’s annex, the police found several young men (all black) and two women (both white), who had all found their way to the motel as the fires and gunshots raged outside. After several hours of violent interrogations, three of the men had been shot dead with buckshot, all at close range: Carl Cooper, 17, Fred Temple, 18, and Auburey Pollard, the oldest victim, aged 19. Surviving witnesses and prosecutors agreed that the police had murdered the young men. The Wayne County medical examiner agreed that Temple and Pollard were shot while kneeling or lying down. The episode, notorious in Detroit at the time and since, is the subject of Kathryn Bigelow’s new film, Detroit, which will bring the story to a national audience for the first time since the original media coverage of its aftermath.

The Algiers was named, like many cheap, mid-century roadside lodges, to suggest the exotic air of a tropical oasis. Sometime after the killings, it was renamed the Desert Inn, an apparent concession to its quickly fading fortunes. In 1979, with Detroit in the midst of one of its periodic renaissances, the hotel was demolished and replaced with Virginia Park. Now, the building is, like so many other grand and plebeian remnants of Detroit’s mid-century “golden age,” buried under a grassy lot, invisible except to those with long memories.

Shortly after the killings, local papers picked up the story, and the three officers were charged with murder. The burial of the Algiers Motel Incident began almost as fast, however. Murder charges against Paille were quickly dismissed when a confession he had made shortly after the shootings was ruled inadmissible by a judge because—incredibly—he had not been advised of his Miranda rights by his colleague who conducted the interview. August was acquitted after a trial before a white jury in a Flint suburb. A second trial of all three officers, for conspiracy, also ended in an acquittal. And that was that.

In July, 1968, a year after the killings, Knopf published John Hersey’s The Algiers Motel Incident, which remains the definitive account of the affair. Hersey’s book has never been well regarded. It received negative reviews at the time, and many readers still stumble on Hersey’s tireless, even tedious documentary method: the book is composed mostly of interviews with the three officers, surviving witnesses (the others in the hotel that night were let go the next morning), and the families of Cooper, Temple, and Pollard.

The book reconstructs at great length seemingly trivial details, like the TV movie on that night in the motel. It dives deeply into the back stories of the major participants, in an effort to give shape to Hersey’s conviction that the “the men and women involved in the Algiers incident were caught up in processes much larger than themselves.” We learn a great deal about Senak’s early police career on the DPD vice squad, which taught him to distrust and fear women (“who gave who the apple?” he asks Hersey at one point). We learn his anagrammatic childhood nickname, “Snake,” and we hear of August’s love of polka and his quiet, dull reserve. We are told of Paille’s Catholic school upbringing and his assertion that, in Black neighborhoods, “these people here, a good part of them are immoral. Any policeman knows that, in those areas.” The book reserves definitive judgment on the question of exactly who shot whom, and when. The police are self-exculpating, and Hersey, who was white, observes that the African American survivors of the motel atrocity distrust him and the white county prosecutors ostensibly on their side. But the book leaves little doubt that the police killed Cooper, Temple, and Pollard, and that they were motivated by a combination of racism, fear, cowardice, and sexual paranoia.

At the center of the book is Pollard, a complex young man, a sensitive aspiring artist and a boxer often relied upon by his friends for his quick fists and hot temper, assets in a fight. Like the others, he was unlucky to take refuge at the Algiers, stranded away from home during a strict city-wide curfew. He was beaten severely in the head and face—according to eyewitnesses, by the stock of a policeman’s shotgun, which broke over his skull. Before he was shot to death, a survivor recalls, Pollard apologized for breaking the policeman’s gun.

“The police didn’t even notify us,” Pollard’s mother tells Hersey. “That’s a hurt feeling.” Rebecca Pollard would often appear in news accounts of the police officers’ trials, and she is a central figure in Hersey’s book, where her matter-of-fact recounting of what has been done to her family seems to conceal a much deeper heartbreak that lurks on the margins of the story Hersey is able to tell. When her elder son Chaney returns from Vietnam after his brother’s death, he suffers what the book calls a “nervous breakdown.” Mrs. Pollard says of him: “I felt pretty bad all the time about his being in Vietnam, I figured something was going to happen to him all the time, I wasn’t never thinking about something going to happen to Auburey.” Their hometown, as it turned out, was deadlier for the Pollard boys than South Vietnam.

As many critics remarked at the time, with some of the typical American grandiosity about such things, the Algiers was a “peculiarly American tragedy.” Bigelow herself has described it this way, as did Hersey. What is meant by this phrase, besides that a racist murder was committed and then covered up, and that such a thing had happened before and would definitely happen again, is never quite clear. There is always something evasive, even self-righteous, about calling a police murder a “tragedy,” as we often do. After all, what makes a tragedy tragic (at least according to Aristotle) is not just that it is terrible—it’s that it’s terrible and it happens for no reason. But if it happens over and over again, then there is probably a reason. If the reason is unjust, that means it’s no longer a tragedy, but something more like an atrocity. Many of Hersey’s critics disliked his painstaking, non-narrative reconstruction of the affair because it lacked grandeur—there was no drama here, no satisfying catharsis, no story, no clear answers, and thus none of the tearful consolation a good tragedy gives us. There is only an approximation of what Mrs. Pollard calls a “hurt feeling.”

I teach at Wayne State, a public university about a mile down Woodward from where the Algiers used to be. When I taught the Algiers Motel Incident this spring, the episode felt uncanny, both acutely familiar and a thousand miles away. I was teaching it in a class timed to the 50th anniversary of the Detroit rebellion, which none of us, me or my students, were alive for, but the atrocity felt ripped from the headlines of Baltimore, Cleveland, Tulsa, and Ferguson. The Algiers Motel incident came to feel like so much of Detroit’s history, as if, like the building itself, the story had sunk into the patchy grass and broken concrete of Woodward Avenue.

For Detroiters of a certain age—to judge anecdotally from the responses of my older acquaintances and neighbors who were alive when it happened—“Algiers Motel” marks not a place so much as a moment in history, like “Kent State” might do elsewhere. It’s an episode that, for some, might bookend the upheavals of the 1960s. It calls together the radicalism of Black Power, when H. Rap Brown visited Detroit and demanded revolutionary justice if the state acquitted the police; the long hot summers in cities across the country; the notoriety of Detroit’s Jim Crow police that awaited southern migrants like Cooper, Temple, and Pollard’s parents. For my students, though, the unfamiliar story of the Algiers Motel Incident belonged to a different timeline: Cooper, Temple, and Pollard were the Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, and Mike Brown of their grandparents’ time, part of the long lineage of young black citizens cut down by the police.

And these killings took place in Detroit, a city that, at least to me—a non-native, and therefore forever an outsider—seems to keep its people close. Unlike Los Angeles or New York or Miami, wealthier cities that hum and churn, demolishing and rebuilding and expanding, in Detroit the effects of July 1967, buried though they are, remain close to the surface of a city that has never stopped contracting.

One of my students realized as she read The Algiers Motel Incident that her dad must have gone to Sunday school with Paille; they were born the same year, she said, and belonged to the same east-side parish. Another reacted with bemusement at Hersey’s attention to Paille’s habit of adding phrases like “all that there” at the end of his sentences, a tic of the upper Midwest that Hersey reads as a sign of confusion or simplicity—“that’s just how my granddad talks,” my student said. And as I read Hersey’s book, I repeatedly paused to look up the names of places and characters he names, experiencing along with my students the sense of surprise and pride they often feel at encountering the city in literature that is supposed to be “good.” Detroit is often mythologized, but, compared to Chicago or New York, it is rarely written about realistically by those who know it, or at least claim to (Angela Flournoy’s The Turner House, Paul Clemens’s Made in Detroit, and Dudley Randall and Philip Levine’s poetry are some of the exceptions in which I have seen this response from my students).

It became clear in our class that my students’ timeline—of police killings, prisons, and impunity—felt like the most tangible legacy of the Algiers. Melvin Dismukes, played by John Boyega in Bigelow’s film, was universally described in the press as “a Negro security guard,” at work at a nearby supermarket that night. A minor player in Hersey’s book, he was a defendant in the second trial, when he and the policemen were charged under a Reconstruction-era conspiracy law with violating the civil rights of Cooper, Temple, and Pollard. Reflecting on the case in a 1992 Detroit Free Press article commemorating its 25th anniversary, Dismukes said that “the only reason my name was linked with them [the police] was to get them off. It would put less pressure on them if they could tie a black person in with it.” Googling his name today brings you results for Melvin Dismukes, Jr. from the web site of the suburban Macomb County, MI Department of Corrections, where he was once incarcerated. The only image result, besides a still of the elder Dismukes from a promotional featurette for Bigelow’s film, is the younger man’s mug shot. In this example, the Algiers’s timeline of a prejudicial police power and a segregated society extends backwards to Reconstruction and the “Negro security guard” and forward to Macomb County prison at the turn of the last century.

In the book, Senak recounts his career going undercover to bust Detroit’s underground gay bars and, as he puts it, “trolling for whores.” This part of his history is, in Hersey’s point of view, a crucial part of the story—of the Algiers Motel incident, and the broader rot of racism, fear, and misogyny it illuminated. The presence of the white women, Juli Hysell and Karen Malloy, at the Algiers seems to have especially enraged the policemen. Hysell and Malloy said they were called “nigger lovers” and had their clothes ripped off by the officers. Defense attorneys tagged them as prostitutes to tarnish their credibility.

On the one occasion that Senak has spoken publicly of the Algiers Motel, in the 1992 Free Press piece, he said that he never speaks of the event, never thinks about it, and has never told his children about it. He confessed then that he dealt with the aftermath of his trial by drinking too much and abusing his wife. But that was all behind him, he claimed, and one can only assume he thinks it is further behind him now. Senak looks to be enjoying a quiet retirement in Brighton, Michigan, a small town north of Ann Arbor. We found him on Facebook; he is an enthusiastic church-goer, enjoys his grandchildren, goes fishing, and posts disapprovingly of the Supreme Court decision on same-sex marriage—he is, apparently, ever the old vice squad cop. Senak has aged well—he’s instantly recognizable from the old press photos from 1968. After enduring Hersey’s painstaking reconstruction of the lives of August, Paille, Senak, Cooper, Temple, and Pollard, seeing Senak’s self-curated digital self is a jarring eruption of a history-making atrocity from the past in the most banal part of the present, Facebook. It’s also a glimpse of a future that seems all too likely: will this be how Tamir Rice’s killer ends up, fishing and hosting family reunions at some up-north lakehouse, giving all the glory to God in a shareable meme?

There is one picture of Auburey Pollard that circulated in the press after his death. He is smiling, a distinctive, bright, sly, almost sarcastic grin. This smile must have looked menacing to the white Northwestern High School teacher who denounced him falsely as a “black militant.” It must have seemed dangerous to the white people who wrote letters to his mother, calling her son a “pimp” who deserved what he got. Only those who knew him well can say anything about the real person who lived behind that smile. For readers of Hersey’s book, and viewers of Bigelow’s film, we can only speculate from a vast distance. Facebook also told me that Auburey’s younger sister, Thelma, lives in a Detroit suburb. She is retired from a long career at the Detroit Public Schools, and her profile features a picture of the Obamas. She never appeared in any news photos from the case, but she looks immediately familiar—she has the same smile as her brother.