1

Dawn Chapman first noticed the smell on Halloween in 2012, when she was out trick-or-treating with her three young children in her neighborhood of Maryland Heights, Missouri, a small suburb of St. Louis. By Thanksgiving, it was a stench—a mixture of petroleum fumes, skunk spray, electrical fire, and dead bodies—reaching the airport, the ballpark, the strip mall where Dawn bought her groceries. Dawn could smell the odor every time she got in her car, and then, by Christmas, she couldn’t not smell it. In January, the stench hung in the air inside her home when Dawn woke her children for school every morning. “That was the last straw,” she told me recently. Dawn made a call to City Hall asking about this terrible smell. The woman on the phone told Dawn she needed to call the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, gave her the number, and abruptly hung up the phone. Dawn called the number, left a message, and then went on with her day.

Her youngest son was napping when the phone rang. Dawn was sitting on the top bunk in his bedroom folding laundry. The man on the phone introduced himself as Joe Trunko from the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Joe spoke gently, slowly. He told Dawn that there is a landfill near her home, that it is an EPA Superfund site contaminated with toxic chemicals, that there has been an underground fire burning there since 2010. “These things happen sometimes in landfills,” he said. “But this one is really not good.”

Joe told Dawn that this landfill fire measures six football fields across and more than a hundred and fifty feet deep; it is in the floodplain of the Missouri River, less than two miles from the water itself, roughly twenty-seven miles upstream from where the Missouri River joins the Mississippi River before flowing out to the sea. “But to be honest, it’s not even the fire you should be worrying about,” Joe continued. “It’s the nuclear waste buried less than one thousand feet away.”

Joe explained how almost fifty thousand tons of nuclear waste left over from the Manhattan Project was dumped in the landfill illegally in 1973. He explained, so gently, that Dawn should be concerned that the fire and the waste would meet and that there would be some kind of “event.”

“Why isn’t this in the news?” Dawn asked.

“You know, Mrs. Chapman, that’s a really good question.”

*

As soon as she hung up the phone, Dawn picked it up again to call her husband; he thought someone must be making a mistake. “Dawn, this is the United States of America,” her husband said. “The government doesn’t just leave radioactive waste lying around.”

Dawn agreed, there must be some mistake. “They wouldn’t do that. Our government would never do that.”

She called the regional office of the EPA to ask about the status of this Superfund site, and when they returned her call, days later, they knew surprisingly little about the fire, Dawn thought. In fact, they wouldn’t even call it a fire, but kept using the term “subsurface smoldering event,” and shared almost no information about what they called the “radiologically impacted material.” They told Dawn it wasn’t dangerous, that the landfill wasn’t accessible to the public anyway. But Dawn had studied the documents Joe had emailed her after their call, so she knew there was more to the story. Joe had even called the next day to make sure she’d received all the files. That made her feel more worried than anything else. “It’s like he wanted this information to get out,” she told me. “Like he was waiting for someone to call and ask.”

Dawn printed out everything Joe had sent and took it to her parents’ house that weekend, where she and her mother were planning to host her daughter’s fifth birthday party in a few short weeks. Dawn had planned to talk to her mother about balloons and cupcake recipes but instead spread out all the documents on the kitchen table. Her brother and husband and both her parents pulled up chairs as she explained about the landfill and the waste. They shook their heads in disbelief. “Someone would have told us about this,” said her father, still shaking his head.

*

After her daughter’s birthday party, Dawn Chapman got to work. Each day she would wake up, make breakfast for her two school-aged children, and put them on the bus. While her younger son watched Sesame Street and ate Cheerios out of a plastic bowl, she searched the Internet, printing out any information on the landfill she could find. During her son’s nap time, she spread the documents out on the kitchen table, leaving the floor unswept, the dishes unwashed, the laundry unfolded in a basket by the couch. She learned that in 1990 the EPA listed the West Lake Landfill Superfund site, which encompasses both the West Lake Landfill and the nearby Bridgeton Landfill, on its National Priorities List. Eighteen years later, when they finally got around to making a decision on the site, their proposed remedy was to install an engineered cap and leave the waste exactly where it is. At that time, in 2008, there weren’t many people in the community who knew there was a nuclear dump in their backyards, and the EPA did little to alert them. “If it weren’t for the fire,” Dawn realized, “we never would have known.”

Weeks later, she found herself standing outside the chain-link fence that surrounds the landfill with half a dozen environmental activists who had gotten hold of some air-sampling equipment. A news crew had come, and there, shivering in the biting cold of the February wind, Dawn gave her first interview about what was causing the terrible smell. She shivered partly from the cold but also because by that point her concern had become righteous anger. She stood with the others on a patch of frozen grass watching the meters and dials on the handheld monitor jump and buzz and whir. She looked up and locked eyes with a woman she’d never seen before.

*

Karen Nickel didn’t know much about the landfill—she’d only just learned about it a few weeks before—but she knew about the waste. Unlike Dawn, she’d grown up in North St. Louis County, and this waste had been here—making her neighbors sick—since before she was born. Karen was nine years old when her parents moved to North County in 1973 in pursuit of good schools, safe neighborhoods, and a big yard for all the children. Her father worked in the lumberyards and her mother stayed home to care for Karen and her siblings.

In their quiet cul-de-sac in North County sometimes as many as fifteen or twenty children would play kick the can in the street or chase lightning bugs in the park until the streetlights clicked on. A creek ran behind the houses on one side of the road and the kids splashed through the water in the mid-August swelter. They fished in the creek for minnows and crawdads and often followed it all the way to McDonald’s to get shakes and french fries. All the children attended the same elementary school, which also backed up to the creek, and heavy rains would bring the water into the field behind the school, a field where they played sports when it was dry. Karen played softball all throughout middle school and high school. She was healthy and active and outside all the time.

When Karen and her husband bought a house in North County for their own growing family, they chose one not far from the neighborhood where she’d splashed through the creek as a girl. But in the summer of 1999 she ran across a parking lot in the rain and then couldn’t get out of bed for days. Maybe she had come down with the flu, she thought. She visited her doctor, who didn’t know what to make of her symptoms. Karen’s blood work showed signs that antibodies were attacking the proteins in the nuclei of her cells. “Lupus,” the doctor told her, years later. He prescribed steroids to manage the symptoms of the disease, and mostly it did manage them. She felt healthy more often than ill. But in July 2012 she collapsed at her daughter’s softball game and didn’t bounce back, didn’t return to work, or to feeling healthy. Her doctor said this might be the new normal.

Karen went to a new doctor, who told her that there’s increasing consensus that lupus can be brought on by environmental triggers, including exposure to contaminants and chemicals, like cigarette smoke, silica, and mercury. In particular, he said, recent studies have shown a link between lupus and uranium exposure. That night over dinner Karen’s husband asked if she remembered a story on the news from a few months before about the creek that ran through her neighborhood. She remembered only vaguely. “Well, it was something about uranium contamination,” he said, looking up from his plate.

“And?” she said.

“And, well, maybe you should look into that.”

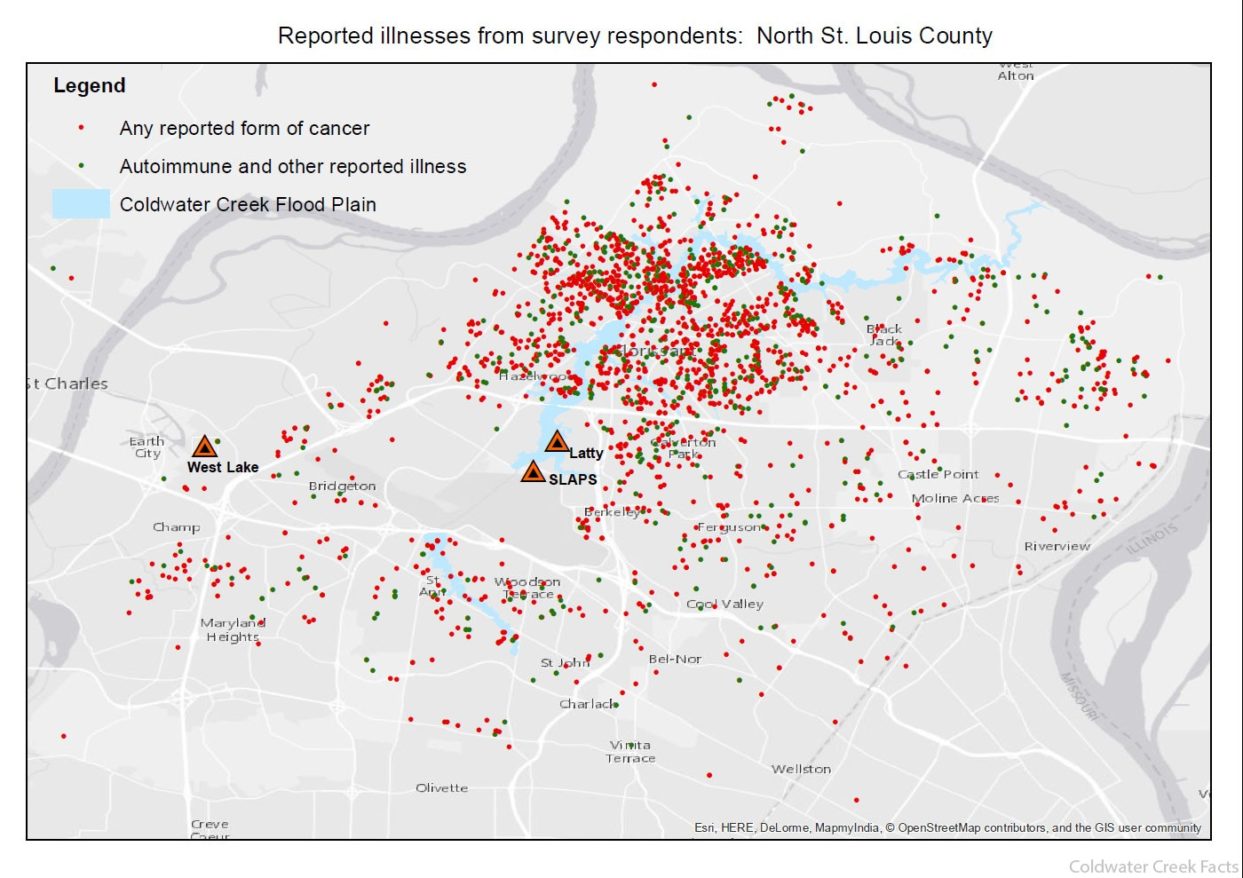

Karen did look into it and learned that many of her classmates and neighbors and childhood friends had died of leukemias and brain cancers and appendix cancers—rare in the general population, but, again, apparently common among those who live or had lived near the creek. It couldn’t possibly be a coincidence.

*

On the day they met at the air-sampling event at West Lake Landfill in early 2013, Dawn followed Karen back to her house and the two stood out in the driveway talking for hours—Dawn about the landfill, Karen about the waste. The next day, first thing in the morning, they were on the phone together. “I’ll bring my kids and come over,” Dawn said. They stayed until late in the evening. “That’s what life looked like, and has looked like ever since,” Dawn tells me on the phone. When Dawn and Karen learned what the EPA had proposed years earlier, in their Record of Decision, they immediately pushed back. They called the media, gave interviews, started a Facebook page. “I remember getting so excited when we hit two hundred members,” Karen told me. “Now we have over seventeen thousand.” They all lobbied their representatives, their senators, City Council members, mayors—even Missouri’s attorney general at the time, Chris Koster, who responded to Karen and Dawn by hiring his own scientific teams to reinvestigate the EPA’s findings, and has now sued the landfill operators. At one point Karen and Dawn had become so fluent in the relevant jargon that public officials began to suspect they were working for some kind of law firm. “Who are you again?” the officials kept asking. “What group are you with?”

“We’re just moms!” Karen and Dawn would answer. “We’re just citizens concerned about the health and safety of our kids and our community!”

Soon after, Karen and Dawn, along with another resident, Beth Strohmeyer, officially formed Just Moms STL, an advocacy group that hosts monthly community meetings, to update their neighbors and community on the progress of their collective efforts. They learned that many of their neighbors near the landfill had developed respiratory diseases and chronic nosebleeds, and some had lost all the hair on their bodies. When they asked the EPA about these illnesses, officials refused to acknowledge any link, or entertain the possibility that the “exothermic reaction” might be causing them. Their scientists had studied the site, they kept saying, and concluded that there was nothing dangerous happening at the landfill, that there is no disaster approaching, that the landfill poses no threat.

But each day Dawn and Karen could see the containment vehicles that arrived to siphon off the thick black leachate seeping from the burning refuse into the ground. The vehicles took the leachate to be treated off-site before it was dumped into the sewer or the river, which supplies the water they drink.

Dawn and Karen decided to look into the fire for themselves. During the day, Dawn downloaded temperature reports from the well monitors at the landfill. At night, she and Karen would sit at the kitchen table with crayons and markers, mapping the temperatures of the wells, using graph paper and trying to remember how to calculate equations they had learned in high school. After a few weeks of making these graphs, they realized the fire wasn’t under control, it wasn’t going out. It was, in fact, moving toward the waste, inching toward the known edge, spreading through the old limestone quarry. Now one thousand feet away. Now seven hundred. In the best-case scenario, the fire chief told them, people need only close their windows, turn off their AC, and shelter in place. In the worst-case scenario, there is nuclear fallout. A disaster is coming, they realized. And worse than that: nothing is standing in its way.

2

As the plane circles downward toward the city, a familiar green stretches for miles in every direction, familiar enough to me that I could call this home. I’m not from St. Louis, but grew up near enough that I came often to watch the Cardinals play in the second Busch Stadium, and to ride in a claustrophobic tram capsule to the top of the Gateway Arch. In high school I drove to St. Louis on the weekends to see my favorite bands play in what was then the Riverport Amphitheatre. A few years later, as a senior in college, I flew out of St. Louis Lambert Airport with a man I loved on a two-month trip to Europe, and flew back here changed and alone.

It’s July when I land this time at the airport. I take the bus to the rental-car office to collect the car I’ve reserved, an exercise in patience since the pace of all things—conversation and business and traffic—moves more slowly in St. Louis than in Houston, where I live now. The calm navigation voice coming through the car speakers leads me onto and off of the highway, down a business strip of big box stores lined with swarming parking lots, onto a narrow road past a farm and into a subdivision of ranches and split-level homes. I stop in front of a raised ranch at the end of the street.

Robbin Dailey opens the door and welcomes me into her home, less than half a mile from the burning landfill. She reminds me of so many mothers I’ve known: the same hair, the same loose-fitting shirt and capri pants, the same open-hearted laugh. Robbin’s husband, Mike, stands to greet me in the entryway, shakes my hand, and then gestures for me to follow him into the living room and sit on the couch. He leans into his brown corduroy recliner, eyes on the muted TV. Robbin sits in a stiff chair across from me, crosses her legs.

Robbin and Mike Dailey moved to this house in 1999, after their kids had moved out and started families of their own. It’s a relief their children never lived here, she tells me. In this neighborhood children fall ill. There are brain cancers and appendix cancers, leukemias and salivary-gland cancers. Up the street from Robin and Mike there’s a couple with lung and stomach cancer. They bought their home just after it was built in the late 1960s.

I ask what they think might happen if the fire ever reaches the waste. The question hangs in the air for a moment as the TV flickers from the far wall. “Look, we know it won’t explode,” Robbin explains. “We’re not stupid. We know that’s not how it works. But just because there’s no explosion doesn’t mean there won’t be fallout.”

We leave the house and climb into her maroon SUV. She lights a long cigarette, rolls down the windows. We drive up the street a few houses, pause as she watches a uniformed man open a gate into one of the backyards and enter—“Testing,” she tells me—and then drive out of the mouth of the street, left at the corner where the street meets the old farm, and suddenly we’re there.

“Jesus,” I say out loud. I’ve looked at thousands of pictures of this landfill, aerial photos and historical photos, elevation photos and topographical maps, but nothing has prepared me to see it in person, this giant belching mound of tubes and pumps and pipes. There’s some kind of engineered cover over the dirt itself, which is supposed to suffocate the fire and capture the fumes. It looks like little more than a green plastic tarp patched together over a hundred acres of sagging hills.

“This is the burning side,” Robbin tells me. “The radwaste is on the other side.” The patchwork is topographical and bureaucratic: the burning side is the southern section of the landfill and falls under the jurisdiction of the Missouri Department of Natural Resources; the radioactive waste is mostly on the northern side, and under EPA jurisdiction. On the burning side, workers drive over the tarp on utility carts, wearing hard hats and work clothes. No gloves, no masks, no protection from the destruction buried underneath their feet. Robbin waves her cigarette at them and we take off down the road, driving the full circumference of the site. It’s bigger than I imagined: two hundred acres in all.

Robbin shows me the pond to the west of the landfill where the leachate is collected, the fence where Franciscan nuns hang ribbons at the prayer vigil they hold every other Wednesday. We drive up to the adjacent property onto which radioactive soil has eroded. There’s a chain-link fence around the entire site. “We call it the magic fence,” Robbin says, laughing in that familiar way.

On the way back, Robbin takes a detour through a series of empty streets that used to be a “nice” neighborhood. “Carrollton,” the sign at the entrance still reads. “They demolished it all,” Robbin explains. “The government bought everyone out because of noise pollution from the airport.” She shakes her head, gives a little cough, grips the steering wheel. “Noise pollution!”

It seems like we are driving past countless streets and intersections and cul-de-sacs, all the infrastructure without any of the houses—without streetlights or driveways or gardens or people. “Mike and I used to come out here and dig up bulbs and plants from the yards,” she says, slowing down and looking out the window. “It was too sad to leave them. When they built this neighborhood it was like a magazine. The American Dream. Look at it now.”

We drive past a parking lot marking the former site of a community center, where children once swam in the pool, spending whole days in the water without sunscreen, riding their bikes home without helmets as the streetlights flickered on.

“Do you think your neighborhood will end up like this someday?” I ask, goosebumps forming on my arms and legs.

“I sure as hell hope so,” she says, tossing her cigarette butt out the window.

3

“Seventy-one years ago, on a bright cloudless morning, death fell from the sky and the world was changed,” President Obama’s speech in Hiroshima begins. It’s May and he’s standing next to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at a podium in front of the Peace Memorial in Hiroshima. His choice of words is interesting, as if death arrived in Japan that morning of its own volition. As if the United States government didn’t have everything to do with it.

“A flash of light and a wall of fire destroyed a city,” he continues, “and demonstrated that mankind possessed the means to destroy itself.” But at that point, in August 1945, there was only one government in the world that had succeeded in generating a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, only one military with an atomic weapon, only one aircraft that opened its bay doors on the morning of August 6 over Hiroshima and dropped a fission bomb containing 141 pounds of uranium, which fell for forty-three seconds before incinerating several square miles of a city and every person, animal, and structure in it.

At first, the Manhattan Project didn’t have a name; it consisted of a loose affiliation of military personnel, politicians, and scientists linked together by special government committees. Arthur Holly Compton—the Nobel-winning physicist leading the team working on fission at the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago—was on one of these special committees. At that time, the idea of a self-sustaining uranium fission chain reaction was still purely theoretical. To prove it was possible, his team needed forty tons of uranium, and they needed it urgently. Rumors had been circulating that the Germans were two years ahead of the Allies in the race for the bomb. This brought Compton to St. Louis, to Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, where he convinced his old friend Edward Mallinckrodt, Jr., to enlist his chemists in the secret government project over a gentlemen’s lunch.

The uranium ore, several thousand pounds of it, arrived at Mallinckrodt in hundreds of containers of various shapes and sizes ranging from large wooden crates to one-gallon paint cans. The twenty-four workers in the new uranium division at Mallinckrodt Chemical Works labored around the clock to process the uranium. Within a month of that gentlemen’s lunch, they began sending the purified uranium back to Compton’s lab in Chicago. Within three months, they were sending a ton a day.

*

Three days after Hiroshima, after the Japanese refused to surrender sovereignty to the US government, Bockscar dropped a plutonium bomb over a small community in the Urakami River Valley. A ring of fire spreading outwards for miles from the hypocenter became a ball of fire, and then a pillar of fire rising forty-five thousand feet into the air.

When Japan surrendered on August 14, Life magazine reported that people across the United States celebrated without reservation, “as if joy had been rationed and saved up for the three years, eight months and seven days” since the attack on Pearl Harbor. Two million people from all over New York flocked to Times Square, where they kissed and drank and danced in conga lines through the street. Scraps of cloth snowed down from windows in the garment district onto people parading below. In Chicago, enormous crowds flocked to the Loop and celebrated with wild abandon.

In St. Louis, the news came over the radio at 2:30 a.m. Bar owners rushed to re-open, and the parents of deployed soldiers tapped kegs in their front yards, pouring beer for their neighbors into pails and buckets. Those who bothered to go to work the next morning threw reams of paper out the windows of office buildings and then descended the stairs to dance through the piles of paper in the street. Impromptu parades sprung up all over the city.

At the Mallinckrodt plant in downtown St. Louis, workers were given the day off. For many of them it was only the second or third day off since they’d begun purifying uranium for a project with a strange name and a secret purpose. Only as they joined the celebrations did they understand what that purpose had been.

4

It’s dark when I spread a stack of government reports out on the hotel bed—each report held inside a binder clip, each hundreds of pages thick. I’ve spent the whole summer wading through thousands of pages of documents like these, all of them full of disturbing concessions and impenetrable jargon. Months ago, when a high-school friend reached out to me asking that I give my attention to this story, she told me that a company tasked decades ago with disposing of nuclear waste for the federal government had instead dumped thousands of barrels of the waste somewhere in North St. Louis County. The barrels were left exposed to the elements for decades, and the waste had leaked into the ground and into the water of a nearby creek.

I did start looking into it, and I haven’t been able to stop. I have learned that although there wasn’t anything especially dangerous about the first ore Mallinckrodt processed in the downtown facility, after the successful “Pile-1” experiment in Chicago, the focus of Mallinckrodt’s work for the Manhattan Project shifted from purifying uranium for lab experiments to purifying uranium for use in an atomic bomb. A different kind of ore began arriving in fifty-five gallon drums marked plainly URANIUM ORE — PRODUCT OF BELGIAN CONGO. The new ore was more concentrated than any other uranium ore on the planet—up to 65 percent pure uranium (versus the .3 percent they had previously considered “a good find”). The workers had to handle this new ore differently: it arrived on vented freight cars and they needed to take care to store it separately from the other ore, the other wastes, and from the processing equipment, and to put all the residue back in the barrels after the uranium was extracted and save it. For what they did not know.

By all accounts, the government knew about the dangers of working with this material, but allowed the uranium workers to continue working with it anyway. Weeks after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, safety officials arrived at Mallinckrodt and demanded that the uranium workers begin wearing badges to monitor their radiation exposure, and that they stop using their hands to scoop the uranium salts into bins and pick through the unrefined ore.

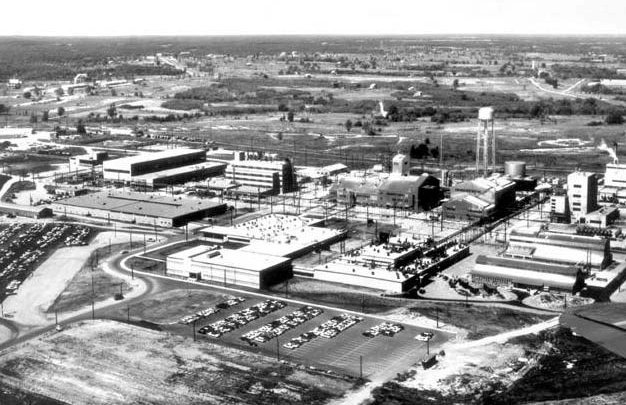

The officials also began looking for a place to store the radioactive wastes, and settled on a 21.7-acre property just north of Lambert Field—at that time it was a municipal airport and an airplane manufacturing base—far outside the edge of town. The base sat on one side of the property; a small creek ran down the other. Beyond the creek was nothing but sparsely populated farmland. When the federal government filed suit to acquire the property under eminent domain, officials refused to disclose the exact nature of the waste “for security reasons.” They assured the local government that the waste they’d be storing there wasn’t dangerous. They shook hands and signed papers. They looked people squarely in the eye.

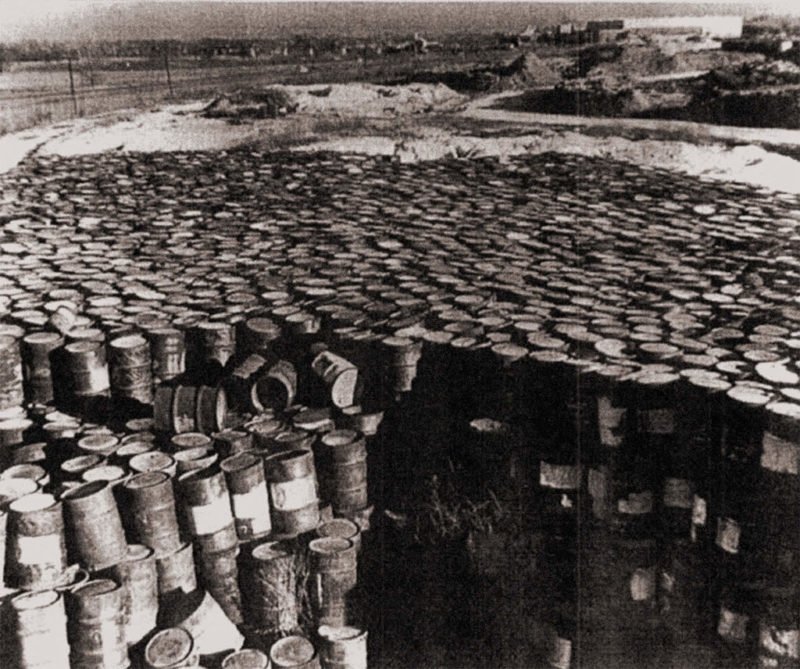

During the next twenty years, truckload by truckload, the green patchwork of farm fields by the airfield turned into a foreign world. Mountains of raffinate rose up across from row after row of rusty black drums, stacked two or three high. Even as those mountains grew taller, the American Dream transformed the fields into subdivisions, brought houses and streets right up to the airport site, right up to the black sand, right up to the borders of the creek. Every time the wind blew it carried radioactive dust into the brand-new parks and gardens and backyards. Every time it rained, the water flowed between the barrels, into their rusting holes, and all the things that water can carry flowed into that small creek.

*

The reports tell only so much, only certain parts of certain versions of the story. The rest I have to piece together using articles in the local newspaper, phone calls with these residents, oral histories collected by others, newsletters from various companies celebrating one anniversary or another. I have learned through months of this piecing that in 1966 the government abruptly cancelled Mallinckrodt’s contract. The wastes had been sold at public auction in 1962, for a lump-sum payment of $126,500. In 1966, the winning bidder moved the wastes to a private storage site about a mile away, on Latty Avenue, and then the company promptly went bankrupt. The next year, the wastes were repossessed and were then sold to another company, Cotter Corporation of Colorado. Records from this second sale indicate that the inventory included seventy-four thousand tons of the Belgian Congo pitchblende raffinate, containing about 113 tons of uranium; 32,500 tons of Colorado raffinate, containing about forty-eight tons of uranium; and 8,700 tons of leached barium sulfate, containing about seven tons of uranium. Surprisingly, the sale also included a few hundred barrels filled with contaminated junk—boots and uniforms and bricks from the Mallinckrodt plant downtown that were hot with radiation. Cotter began drying the piles of raffinate in a giant kiln and shipping the dried material in open train cars to their facility in Colorado. After a few months, nothing was left except the barrels and the 8,700-ton pile of leached barium sulfate.

In my pile of reports there is a series of letters from Cotter to the Atomic Energy Commission, in which Cotter tries to convince the government to take these wastes back. Commercial disposal would cost upwards of two million dollars (about twelve million dollars today). They couldn’t afford it. They knew that the AEC was using a quarry at the recently decommissioned second Mallinckrodt facility at Weldon Spring, roughly twenty miles southwest of the airport, as a dump for nuclear waste. They asked the AEC if they could use it, asked for guidance, and for help.

That help never came.

In 1974, a government inspector arrived at the storage site on Latty Avenue and casually asked a question about where the barrels and the leached barium sulfate had gone. Someone working at the site—a driver or a security guard, maybe—mentioned he thought they had been put in a landfill. A lengthy investigation discovered that from August to October 1973, a private construction firm drove truckloads of the leached barium sulfate—along with roughly forty thousand tons of soil removed from the top eighteen inches of the Latty Avenue site—to West Lake Landfill, all around the clock, sometimes in the middle of the night. To the landfill operator it looked like dirt, so he waved the trucks in and charged them nothing, using it as landfill cover over the municipal refuse.

*

I keep hoping I’ll find something—a graph, a chart, a single sentence or letter or memo—that will make sense of all of this. But the reports express the detection of this contamination in charts, as numbers and statistics. They’ve found contamination at the airport, in the drainage ditches leading away from the airport, and all along the creek—along the trucking routes, in ballfields and in parks and gardens and backyards, in driveways, in people’s basements and under their kitchen cabinets. Even now, as I write this, they are still trying to figure out just how far it has spread.

The reports measure the health risk of exposure to this contamination as an equation, with a threshold of acceptable risk. But what the reports don’t say is that the contamination has already done so much damage that cannot be measured or undone. The Mallinckrodt uranium workers are some of the most contaminated in the history of the atomic age. So contaminated, in fact, that in 2009 all former Mallinckrodt uranium workers were added as a “special exposure cohort” to the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act. The act provides compensation and lifetime medical benefits to employees who became ill with any of twenty-two named cancers as a result of working in the nuclear-weapons industry. Because of this special cohort status, if a former Mallinckrodt worker develops any of these named illnesses, exposure to the uranium is assumed. But the people who live near the creek didn’t work for Mallinckrodt. They aren’t entitled to compensation or to medical benefits.

A woman named Mary Oscko, for instance, has lived her whole life in North St. Louis County, most of it near that small creek. Now she is dying of stage-four lung cancer, though she has never smoked a day in her life. Shari Riley, a nurse who lived near the creek, died recently of appendix cancer—rare in the general population, but several dozen cases have been reported among those who live or lived near the airport or along the creek. My friend—the one who contacted me about this story—never lived in St. Louis, but her mother grew up two houses away from that creek. My friend suspects that her mother’s exposure to the contamination as a child changed her DNA in ways she passed on to her children, which would explain why my friend was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer a few years ago, at the age of thirty-five. Could it also explain why my friend’s mother once gave birth to a set of conjoined twins? Conjoined twins are an anomaly in the general population, but these make the fourth set born to women who grew up near that creek. And those are just the ones we know about.

*

The reports don’t acknowledge these stories, these illnesses, those who are dying or dead. Most residents of St. Louis—including and especially the residents of predominantly African-American neighborhoods—don’t even know the contamination is there. It creates an impossible situation for health professionals in St. Louis, like Dr. Faisal Khan, director of the St. Louis County Department of Public Health. “In community meetings people have narrated heartrending stories to me,” he says, “stories about their own cancers or their loved ones or their children. I’ve had people walk up to me and hand me pictures of their children who have died of cancer. They’ve given me hair and teeth and nail-clipping samples and say, ‘Could you please have these tested?’”

They’re looking for a cause, looking for someone to blame, looking for a location toward which to direct their rage and bewilderment and grief. More than anything else, they want to know why.

Dr. Khan told me he often finds himself saying, “I just don’t know.”

5

I don’t recognize the woman who answers the door at Kay Drey’s house. I’ve never met Kay Drey but I’ve seen her photo countless times: her silver hair cut in a short wavy bob, her tall slender frame standing slightly slouched. She’s in her eighties, I think, but this woman answering her door is my age, my height. She flashes a broad smile and leads me to the dining room, where the table is piled with papers sorted into cardboard-box lids, then into the kitchen, where Kay is writing something at her desk. Kay stands to greet me; we shake hands and I follow her to the dining-room table, where we sit. A paraplegic dog comes over to my leg and demands to be scratched. “Moxie,” Kay tells me, introducing the dog. “You might as well go ahead and scratch her because she won’t leave you alone until you do.”

Kay Drey lives in University City, another suburb of St. Louis, but one where the homes are older and larger and set farther back from the streets. Kay’s husband, Leo Drey, was a conservationist, a forester, and Missouri’s largest private landowner before he donated most of his land to charity. He passed away in 2015 of complications from a stroke. Kay’s health is also failing now—a fact that becomes apparent as she tells me multiple times that her memory is not what it used to be. She relies on Post-it notes, she says, which she sticks to the shelves above her desk in the kitchen. On one orange Post-it she’s copied a quote from Hugh Hammond Bennett, the first director of the US Soil Conservation Service: “It takes nature,” she has written in the erratic scrawl of someone who cannot hold a pen without difficulty, “under the most favorable conditions, including a good cover of trees, grass, or other protective vegetation, anywhere from 300 to 1,000 years or more to build a single inch of topsoil.” She pokes this note, hard, with the bent tip of her finger. “The topsoil around that landfill is ninety feet deep,” she says. “Some of the richest soil in the world, and it is ruined forever.”

Kay repeats herself only a few times during the three hours we sit in her dining room, and it’s in these repetitions that I learn what is important to her: that she spent her life fighting for housing integration before she began the fight against nuclear proliferation, that any amount of radiation exposure is bad for your health, and that she gave her first speech against nuclear power on November 13, 1974, the day that, as is widely believed, Karen Silkwood was run off the road in Oklahoma. In that speech, Kay argued against the building of a nuclear power plant in Callaway County in the middle of the state, about one hundred miles from her home in St. Louis. Originally the plan was to build two reactors, but activists like Kay fought the plan and they built only one. “That was a victory,” she says. She’s had other victories, too: she tells me that she’s the one who got the Department of Energy to acknowledge the radioactive waste at Lambert and won a twenty-year battle to get it removed. She also tells me she identified contaminated water near the second Mallinckrodt plant at Weldon Spring, and made sure a water-treatment plant was constructed so that radioactive waste wouldn’t be dumped into the Missouri River. “It is important to pause to celebrate those victories, no matter how small,” she says. “Because that is what gives you courage to fight the really big battles, the ones you have to fight even though there’s no chance of winning.”

She asks if I’d like to see her basement. “Most people do,” she adds. We climb down a set of steep stairs and she flips a switch, illuminating an overhead fluorescent light. “LED,” she corrects me, even as I think it. Four-drawer file cabinets line two walls, all meticulously indexed and cross-indexed in an ancient oak card catalog that sits in the center of the room. Thousands of documents are housed here, and she knows exactly where to find any given report. “In St. Louis we have the oldest nuclear waste in the country,” she observes, “because we purified all of the uranium that went into the world’s first self-sustaining chain reaction.”

The moment I mention the EPA, she puts her hand directly on the drawer where the woman upstairs—“My librarian,” Kay tells me—has filed the EPA’s Record of Decision for the West Lake Landfill, and then on the drawer where I might find studies that contradict the EPA’s assessment that the radioactive waste in the landfill doesn’t pose a threat to residents—the radiological surveys of the site conducted in the 1970s and 1980s by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Department of Energy, as well as more current studies by independent researchers. She explains that the radioactive waste buried in West Lake Landfill covers about twenty acres in two locations in one or many layers, estimated at two to fifteen feet thick, some of it mixed in with municipal refuse and some of it sitting right at the surface. It is in the trees surrounding the landfill and the vacuum bags in nearby homes. This waste contains not only uranium, but also thorium and radium, all long-lived, highly radio-toxic elements. And because Mallinckrodt removed most of the naturally occurring uranium from this ore, the Cotter Corporation, in effect, created an enriched thorium deposit when they dumped the residues at West Lake Landfill. “In fact,” Kay muses, “West Lake Landfill might now be the richest deposit of thorium in the world.”

Thorium and uranium in particular are among the radioactive primordial nuclides, radioactive elements that have existed in their current form since before Earth was formed, since before the formation of the solar system even, and will remain radioactive and toxic to life long after humans are gone. We’re sitting back in Kay’s dining room when she pulls out a tiny booklet labeled “Nuclear Wallet Cards.” What its intended purpose is, I don’t know, but Kay flips to the back to show me the half-life of Thorium 232: fourteen billion years, a half-life so long that by the time this element is safe for human exposure, the Appalachian Mountains will have eroded away, every ocean on Earth’s surface will have evaporated, Antarctica will be free of ice, and all the rings of Saturn will have decayed. Earth’s rotation will have slowed so much that days will have become twenty-five hours long, photosynthesis will have ceased, and multicellular life will have become a physical impossibility.

“You know, tritium is my favorite,” Kay tells me before I leave. It’s produced as a side effect of operating nuclear reactors and released into the air, or leaks into the waterways; it contaminates the water supply and condenses in our food. One official who worked at the nuclear reactor Kay had tried to prevent once told her that tritium was no big deal. “It only destroys DNA molecules.” A few years ago they found tritium in the groundwater in Callaway County. “There is no way to remove it,” she says.

As I’m standing to gather my things, Kay goes to retrieve an extra copy of the Nuclear Wallet Cards booklet that she wants me to have. The woman who answered the door—Kay’s librarian—comes back to keep me company while Kay is out of the room. “I was her husband’s caretaker,” she tells me. “When he left, I stayed to take care of her.” Kay returns with a warning of a nasty thunderstorm blowing in. I mention my disappointment that the storm might prevent my visit to the Weldon Spring site. After it was decommissioned, the plant—a second one run by Mallinckrodt—was found to be so contaminated that the Department of Energy eventually entombed the whole site in layers upon layers of clay and soil, gravel, engineered filters and limestone rocks, creating a mountain covering forty-five acres, containing approximately 1.5 million cubic yards of hazardous waste. With its own educational center located near the base, the containment dome has become a kind of memorial for a tragedy that hasn’t finished happening. The top of the dome is the highest point in the county.

“Oh, you don’t want to go there anyway,” Kay says, waving the idea away with her slender hand. “It’s leaking.”

6

The rain comes down in sheets so thick I have to pull my car over to the side of the road. It’s early afternoon, but the sky turns dark as dusk. It’s not the first time I’ve been stuck in a storm like this, the kind that comes up out of nowhere and falls on you all at once. Wipers and headlights become useless; nothing to do but stop and wait it out. It’s a thin little sliver of a storm, I see on the radar on my phone, so I know it will pass as quickly as it arrived, but even still, this time I’m wasting makes that tired, burning feeling I’ve been carrying around in my back more acute.

It’s caused, perhaps, by a contradiction I can’t resolve: that the massive crime here began with a belief in a kind of care, a belief that protection comes only in the form of wars and bombs, and that its ultimate expression is a technology that can destroy in a single instant any threat to our safety with perfect precision and efficiency. But hundreds of thousands lost their lives to those bombs in Japan, and the fallout from building them has claimed at least as many lives right here at home.

There is no one to arrest for this, to send to jail, to fine or execute or drag to his humiliation in the city square. Even if Karen and Dawn win their fight and convince the government to remove every gram of radioactive waste in the landfill and the creek and the airport and the backyards and gardens here, people will still be sick. Thousands of them. Chronic exposure to radiation has changed their DNA, and they’ll likely pass those changes on to their children, and to their children’s children, and on and on through every generation. In this regard, no one is immune.

*

My mom puts dinner on the table but my grandmother refuses to eat. “Not again,” my mom groans, slamming her silverware down and rolling her eyes.

“It happens,” my mom’s husband explains to me behind the cover of his raised hand, “when something throws off her routine.”

My grandfather died a month ago, and now that Grandma is living in the spare bedroom, my mom has learned there was a lot my grandfather did not tell her. My mom is stretched thin with the sudden responsibility of it all: taking care of my grandmother, who has apparently been suffering from dementia for the last twenty years; cleaning out the house; selling all of their possessions at auction; her own inconsolable grief.

“You don’t have to eat if you don’t want to,” she says, her tone as calm and even as she can muster. “But I’m not making you anything else.”

Grandma throws a weak tantrum at this—she pushes her chair out from the table, arranges her walker, shuffles out of the room. She is too old and feeble to “storm” out, but I think that is how she wants us to understand her actions. I laugh a little to myself when the television clicks on, Pat Sajak’s voice on Wheel of Fortune bellowing through the house full blast: “Do we have a U?”

“It’s not funny,” my mom scolds, retrieving a bottle of wine from the fridge. “Let’s change the subject. What are you doing here, anyway?”

I tell her a short version of the story: there’s a landfill, there’s a fire, there’s nuclear waste left over from the Manhattan Project. People are dying of rare cancers. But the short version of the story always leads into the long version, and soon the bottle of wine is empty. My mom’s husband is doing the dishes, half listening. His health has been deteriorating in the years since he retired—he gets light-headed, and increasingly can’t always feel his feet or his hands. “Peripheral neuropathy” is the term for it, I think. It’s becoming harder and harder for him to help around the house. The dishes are one thing he can do to feel helpful, balancing his weight against the sink.

“So then all this waste is just sitting in giant piles at the airport,” I say.

“Right there by the ballfields,” he interrupts, putting a plate into the dishwasher, but I don’t fully hear him. He is a man who likes to know things, and to explain them even if they do not need explaining. I’ve learned to tune it out.

“Then the government holds an auction and sells the waste to a private company. Who knew there was a market for nuclear waste?” I say while my mom opens another bottle and refills my glass. “And then the company that bought it went broke and another company took it over. They shipped most of it to themselves out in Utah. . .”

“Colorado,” my mom’s husband interrupts again. I look up this time. “We were shipping it to Colorado.” He comes over, places his hand on the back of a chair to steady himself. “It was months out there shoveling that dirt into the train cars. Yellow and red and white: odd colors for dirt, if you ask me. We’d fill up the gondolas and them ride them over into the dryer, then jump off and ride the dry ones out the other side.”

Suddenly I am completely sober. “You have to tell your doctor this,” I say. “Mike! You were right there in it! You have to tell your doctor. You have to file a claim with the government.”

He shrugs his shoulders, sitting down in the chair. “What good would that do? I’m seventy-five years old.”

*

Later, I watch him as he shuffles from the kitchen to the living room. He moves so slowly, each step so tentative. He sits down on the couch to catch his breath.

Peripheral neuropathy can be one side effect of radiation exposure, but it might also be caused by him having smoked for the last sixty years, or by him having worked on trains for fifty years; years after he shoveled those radioactive wastes, he was exposed to Agent Orange during a train wreck. It would be an impossible case to make with the government, to pinpoint radiation as the one thing. Besides, he’s the kind of man who thinks it is unpatriotic to accuse the federal government of making mistakes.

His eyes droop, losing focus, and then his head sags to his chest. Grandma falls asleep, too, both of them folding over on themselves. My mom shouts for them to go to bed. She isn’t angry, just loud because they are both nearly deaf. I hear the sounds of running water, of doors opening and shutting, of ancient bodies surrendering to age. My mom sighs, pats my hand, tells me she’d better get off to bed also. When the bedroom door closes behind her, I turn off all the lamps, and sit in the blue light of the flickering TV.

7

It is afternoon when I park my car in the EPA Region 7 parking lot and rush toward the door. The EPA Region 7 offices are located in a sprawling modern government building in a suburb of Kansas City. The small conference room just to the side of the main entrance is filled with a surprising number of people. Curtis Carey introduces himself as the director of public affairs. He’s the one who arranged this meeting after our phone call last week. He was vetting me then, and told me he’d try to set something up with a few of the technicians. I wasn’t expecting much. He introduces me to Mark Hague, the federally appointed administrator for Region 7, and also to Mary Peterson, director of the Superfund Division. Also present: Brad Vann, the new project director at the West Lake Landfill, and Ben Washburn, who does public affairs work too. I tell a quick story about getting lost in the backwoods while my phone was dying on the way here to break the ice. “I thought I was going to have to get married to a farmer and start my life over again!” I say. No one laughs.

“Here are the ground rules,” Curtis Carey begins. “Everything is on the record. You have one hour.”

An hour isn’t much time with which to get anywhere with anyone, much less the five humorless strangers in this room. During our too-short conversation I learn that the EPA has over 1,300 sites in the Superfund program, and Region 7 alone has ninety-eight sites on the National Priorities List. Each of these communities is demanding that their toxic sites be scrubbed clean. “And the process is lengthy,” Brad Vann tells me. “The investigations are lengthy, and then there’s all the time to collect [and] evaluate the data—to get to this point where you can make a decision on a remedy takes time. And unfortunately, sometimes it takes a lot of time, depending on the complexity of the site.”

“Why not remove the waste?” I blurt out. “Just to be sure. Just to be safe.”

“It’s not as clear-cut as it might seem,” Brad says. “There’s more to excavating a landfill than sticking a backhoe in it. There is a process we must follow by law.” The law he’s referring to is CERCLA, which mandates that the risk to human health must cross a certain threshold before the EPA can take any action at all. He sighs heavily.

“Our decisions have to be based on science,” Mary Peterson interrupts. “They can’t be based on emotion. They can’t be based on fear. They have to be based on sound science and the law.”

According to the EPA, the science shows that there is low-level nuclear waste buried in a landfill in suburban St. Louis. Mostly it’s covered; mostly it’s inaccessible. But these findings do not alleviate the community’s concern. The landfill sits in the floodplain of the Mississippi River. What if there is a flood? What if the fire spreads and comes in contact with the radiological material? Either of these would create a disaster, and neither requires a great feat of imagination to bring into the realm of the possible. But the law doesn’t offer a framework within which to consider anything that hasn’t already actually happened yet.

“So the community is asking us to use our imagination,” Mary explains, “and generate hypothetical scenarios in order to evaluate the risk. We don’t have any real data to rely on because that’s not the reality. Those things have not happened. If it had become reality then we could collect real data and say, okay: This is the impact.”

I know this isn’t how risk evaluation works, but I’ve heard her say this before, in footage of a community meeting several years ago, when she gave a PowerPoint presentation about the health risk assessment for the site. The presentation is convoluted and technical, and the whole thing comes down to an equation. One woman in the audience can’t handle this. She stands and takes the mic. She wants to know about the process, why the EPA is withholding certain information. “Did a cost-benefit analysis determine whether we are worth saving?” she asks, dropping the mic, fighting back tears. Behind her, her husband holds up photographs of their two children, both dead of rare cancers.

Dan Gravatt—who was the project manager for the West Lake site at that time, their point of contact, the man who should be their advocate and ally—stands from his chair and strides to the front of the room, laughing to his colleague as he takes the mic. He explains the process in simple language, speaking slowly, raising his voice oddly on certain syllables in a kind of singsong, clearly straining to keep his tone neutral and calm and flat. The effect is deeply patronizing, infuriating even. He goes on for some time about the bureaucratic machinery behind the scenes of the EPA, the process through which their decisions are reviewed and re-reviewed. “The National Remedy Review Board asked for more tests,” he says. “That work is still being done. When that work is done, and the supplemental feasibility study is amended to include that new information, we’ll go back to the National Remedy Review Board, and they’ll have another crack at it. . .” He’s interrupted here by someone in the audience shouting something I can’t make out.

This is an important moment, because it’s when a lot of things go wrong. The interruption unnerves Gravatt and the strain to remain calm and neutral becomes too much. He shouts, “I’m not done!” and lowers the mic for a moment to recollect himself. Many people begin shouting—the parents holding up the pictures of their dead children, Dawn and Karen, Robbin and Mike. The camera pans across the room. Mostly it’s impossible to make out what the crowd is saying, but I hear the words, “They’re not your dead children!” and then a shuffling of chairs. Gravatt tries to continue, raises the mic to his mouth, is interrupted again. He laughs—a nervous response maybe, but the optics are not good. At this instant the meeting breaks down, Karen and Dawn and most of the community members storm out.

After that meeting, Gravatt stopped working on West Lake—another project, another division. The head of Region 7 was also suddenly working in a new position, and Mary Peterson, formerly the deputy director of public affairs, became director of the Region 7 Superfund program. That’s when Brad Vann came on board and immediately tried to get the project back on track, improve transparency, expedite certain studies, move forward on a final remedy for the site. But none of this has repaired the relationship with the community, which might have been irrevocably broken from the start.

At the end of the hour the room empties except for the public affairs director, Curtis, who watches me turn off the recorder and pack up. There are documents and links he wants to send to me, he says, things that came up in the meeting. He wants, very much, to be helpful. He admits they are trying hard to mend their relationship with the community but their efforts just aren’t really going anywhere. I suspect they see the community—the moms in particular—as problematic, difficult.

“Look,” I say, still telling myself that I am neutral in all of this. “They have no power whatsoever to change their situation. They can’t get out there with shovels and dig this stuff out of the landfill. They can’t put out the fire, or stop the leachate from seeping into the groundwater. They feel like they can’t protect their children, or go outside, or breathe the air. They’re powerless.” He looks down toward his hands, nodding as I speak. I do not envy him. “From their perspective, the EPA does have the power to change their situation. You have all the power. And you’re choosing to do nothing at all.”

8

Uranium, thorium, Agent Orange, dioxin, DDT. I am thinking of all the ways our government has poisoned its citizens as I board the plane that will take me back home. The sky grows darker; blue gives way to purple, to red and orange near the horizon. I read recently about a housing project in St. Louis, the infamous Pruitt-Igoe, where the government sprayed nerve gases off the roof to see what effect it would have on the people living there—testing it for its potential use as a weapon in war.

“On every continent, the history of civilization is filled with war, whether driven by scarcity of grain or hunger for gold, compelled by nationalist fervor or religious zeal,” President Obama says during his speech at the Peace Memorial in Hiroshima. “Empires have risen and fallen. Peoples have been subjugated and liberated. And at each juncture, innocents have suffered, a countless toll, their names forgotten by time.” At no point during this speech does he apologize for what some have called a war crime. The closest he comes is this: “Technological progress without an equivalent progress in human institutions can doom us. The scientific revolution that led to the splitting of an atom requires a moral revolution as well.”

A 2005 Gallup poll showed that a majority of Americans still approve of the dropping of bombs on Japan. Admittedly, this is down from near-total approval in August 1945, but it’s hardly a “moral revolution.” One factor in the decision to use the bomb was that their destructive power would end the war and save American lives—some estimated as many as a million American soldiers would have perished in a ground raid on Japan. Does saving one life require taking another? Must they both be soldiers, loyal to their countries and their neighbors? After Nagasaki was bombed, a woman walked through the burning streets asking for water for her headless baby. A four-year-old boy burned alive under the rubble of his crushed house was crying out, “Mommy, it’s hot. It’s so hot.” President Truman called this bombing an “achievement” in his solemn radio broadcast from the USS Augusta: “The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold.”

In the last few months of his term President Obama was reportedly considering the idea of adopting a no-first-use policy on nuclear weapons—an official promise that we would only use them in response to an attack by our enemies—but ultimately his advisors talked him out of it, arguing that it is our responsibility to our allies to maintain the illusion of ultimate power. Now that we have a new president with access to the nuclear codes we must face the consequences of projecting, and protecting, that illusion.

There are about sixteen thousand nuclear warheads in the world right now, enough to destroy the planet many times over. The United States and Russia own 90 percent of these, and though various treaties prevent them from making additional weapons, both are working to modernize the bomb-delivery systems they do have. The US government recently approved a plan to spend one trillion dollars over the next thirty years to make our arsenal more modern, accurate, and efficient.

One trillion dollars. This number is staggering, not least of all because one factor—a minor one but still a factor—deterring the EPA from fully excavating the radioactive waste created by the program that developed these nuclear weapons in the first place is how much it will cost. Maybe as much as $400 million. That’s a lot of money for an EPA project. Budgets are not so simple that one government program—like the Department of Defense—could direct money to another, but the fact that they are not does makes our priorities apparent.

Even if every gram of radioactive waste were removed from the landfill, where would it go? There are facilities in Idaho and Utah willing to accept it. But those facilities are located in communities, or near them, and those people don’t want this waste in their backyards or their gardens or their rivers or their drinking water either. Even if we box it up and send it in train cars to remote places, it will be there, ready and waiting to kill any of us long after we’ve forgotten where we put it, or what “it” even is.

*

“Why should we tolerate a diet of weak poisons, a home in insipid surroundings, a circle of acquaintances who are not quite our enemies, the noise of motors with just enough relief to prevent insanity?” Rachel Carson asks in Silent Spring. Nothing is sacred, or safe, or protected. As a species we have evolved to recognize threats to survival: plants we cannot eat, animals we should not approach, places we cannot safely go. Fear of the other is perhaps an enduring trace of this ancient instinct: that barbaric impulse to attack and destroy anyone different from ourselves, anything we do not understand. But increasingly it seems our ability to invent technologies that destroy one another has evolved faster than our ability to survive them. Carson asks: “Who would want to live in a world which is just not quite fatal?”

Not all radiation is fatal. Radiation is around us always, and each of us are exposed to radiation on a daily basis: from the sun, from the dirt, from sources we would never think to suspect. We ourselves are a source of radiation, since each of us also contains radioactive elements we carry inside our bodies from birth. Throughout our lives we are constantly irradiating one another, not only with charged microscopic particles but also with suspicion and fear and blame. We find infinite directions in which to project our rage and bewilderment and grief.

*

“Do you ever think about just walking away?” I asked Dawn Chapman recently. She’s just learned that her own daughter has developed a tumor on her salivary gland. It’s not cancer, the doctors say. Not yet.

“I don’t know. I dream,” she answers. “This weekend my husband and I dropped the kids off with my family and drove around and dreamed for a while about what it would be like to walk away. But I don’t know how to walk away from it even if I wanted to, knowing what I know about what’s going on, how it’s hurt people. In the end, I’m not even fighting to win. And even if we could win, a win isn’t what you think it is. A buyout isn’t a win because we could move but this poison would still be inside us.”

For Karen, winning means the government finally caring for its citizens like it has always promised it would. “I am shattered. I am broken,” she says. “And now my children and my grandchildren have those chances of being sick as well. Our human rights are being violated and it has to stop. It has to stop here.”

*

As the plane lifts off the ground, I open the tiny window shade to see, one last time, that familiar green that never fails to make some bell in me ring. This place has always been a confluence of things, like the two rivers that converge just north of the city, where the glaciated plains meet the Ozark Highlands, where an eroded mountain range called the Lincoln Hills rises now only a few hundred meters above the alluvial floodplain, all of it pushed into place by the Laurentide Ice Sheet half a million years ago. All of it divided into neat rectangles and squares by city streets, subdivided, fenced into single lots—as if a few planks of wood and slabs of concrete could isolate any one place from the world.

We are all connected. The rivers and streams and tiny creeks wind through the city and go on winding. They twist and bend and run backward on themselves, changing course and direction a thousand times over the ages. The water swells and leaves its banks with the seasons, swells into the streets we build, and our backyards and gardens, into the places we never think of because we do not want to see them: our landfills, our factories, our toxic dumps, all of the remote places we send our worst creations. There is no fence to keep it all out. The disaster that approaches is ourselves.