In the kitchen of the No Place Like Home exhibit at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, where the galleries are transformed into a domestic apartment, curator Adina Kamien-Kazhdan has installed a sculpture of a two-meter-high food grater. Entitled The Grater Divide (2002), the work, by Lebanese-born Palestinian-British artist Mona Hatoum, speaks to the current climate and context of Israeli contemporary art, where the Ministry of Culture has frequently clashed with left-leaning arts groups and where the effects of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, which tries to block Israeli artists and Israeli funded groups from exhibiting globally, on the Israeli art world are being debated everywhere. Palestinian and Israeli artists alike are wrestling with issues of identity and home.

Whether the venue is the Israel Museum, an international institution that receives less than 15 percent of its annual income from the state; the Petach Tikva Museum, funded by the municipality; the Ein Harod Museum, funded by kibbutzim; the Umm El Fahem Gallery of Palestinian Art, funded by the Israeli government; nonprofit arts collectives, who piece together modest funding from diverse private and public sources; or commercial galleries who are in active pursuit of global collectors, funding is precarious, and political and economic issues are often inextricably intertwined with aesthetic concerns.

Leading a spring tour of exhibits at the Israel Museum for Artis, a nonprofit that brings curators from throughout the world to Israel for contemporary art research trips, Mira Lapidot, the Yulia and Jacques Lipchitz chief curator of the arts, raises the big question: “Is there a moral commitment for art to be engaged with what’s happening in the world?” A one-week trip delving into the contemporary art scene, designed for Artis by Chen Tamir, curator, CCA Tel Aviv and associate curator Artis provides a resounding answer: yes.

A concern for what’s happening in the world, and more specifically in Israel, is at the heart of socially engaged photographer Ron Amir’s show, Doing Time in Holot at the Israel Museum, an exhibit that focuses on asylum-seekers from Eritrea (mostly Christians) and Sudan (mostly Muslims) who are currently being detained in open prisons (detention centers) in the southern Negev. Often there for up to one year, detainees have absolutely nothing to do. “The idea is to discourage them from staying in Israel,” said Amir, who befriended the detained asylum-seekers by sharing food with them, eventually establishing personal relationships. He focused on their life outside the center buildings rather than inside, “to make people be the center,” convinced that these images would be more surprising than the detention center itself. In a long video shot by Amir that accompanies the photo exhibit, there is no narrative. “It’s about free time in Holot,” said the exhibit’s curator Noam Gal. “People sit there, and nothing happens. They drink coffee and they smoke cigarettes.”

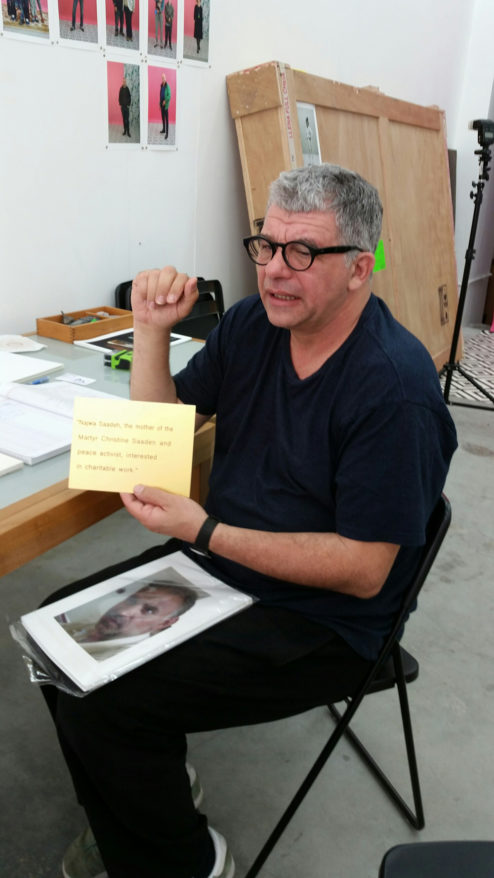

Renowned photojournalist and activist Miki Kratsman has a direct view of the asylum seekers from his storefront in the Florentine neighborhood of Tel Aviv. Kratsman, who lives upstairs, describes the space as a “store that doesn’t sell anything.” The area is full of asylum seekers; hundreds live across the street from him in a building whose façade is covered by a maze of intertwined electric lines. “They come here and I photograph them. I do not ask their names. I do not publish anything. My only publication is on the wall. When they leave, I give them a print of the image for free.”

Kratsman, who came to Israel from Argentina when he was twelve, boasts that by the age of sixteen he was already attending demonstrations. Since that time, he has served in the army, worked for thirty years as a photojournalist for Hadashot and HaAretz, mainly in the occupied territories, and, until two years ago, served as the head of the photography department at Israel’s leading art school, the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. Kratsman co-founded Breaking the Silence, an organization of veteran combatants who have chosen to speak out publicly about the realities of everyday life in the Occupied Territories. “They call us traitors,” Kratsman said.

Kratsman, whose controversial show of three thousand portraits of Palestinians at Tel Aviv Museum (a joint exhibit with the Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei) was canceled because of political pressure, gave me a sneak preview of a video that he is now editing from 2015 to 2016 when he attended a demonstration in the Palestinian village of Nabi Salih. “Many people were seriously injured there,” he said, explaining that he shot video without any specific idea what he was going to do with the footage. Subsequently, he has decided to edit the video according to the sounds of the shooting. As his video camera captures the confrontation, we hear the sounds of bullets, teargas, and grenades.

Kratsman now has sixty thousand followers on his Facebook page, Miki Kratsman: People I Met, and almost sixteen thousand likes, most of them from Palestinians, on the site where he uploaded the faces of eight thousand Palestinians, many of the photos taken at a huge parade in 2007. Kratsman asked viewers to put a circle around the people who were martyred and to send him information of the whereabouts of the others. “Only two people wanted their photos removed,” he said. “For this project, somehow, the comments became the output.” He cited two comments: “See him in the streets. He is still alive,” said one follower; “That child is now twenty-three and he was killed today in Jenin,” wrote another.

But despite his passionate activism, Kratsman feels deep loyalty to Israel. “I would prefer to boycott only the settlements,” he said, “and not boycott all of the country. I cannot boycott myself. I wake up every morning. The problem is that I am an optimist. I can’t live in any other place.”

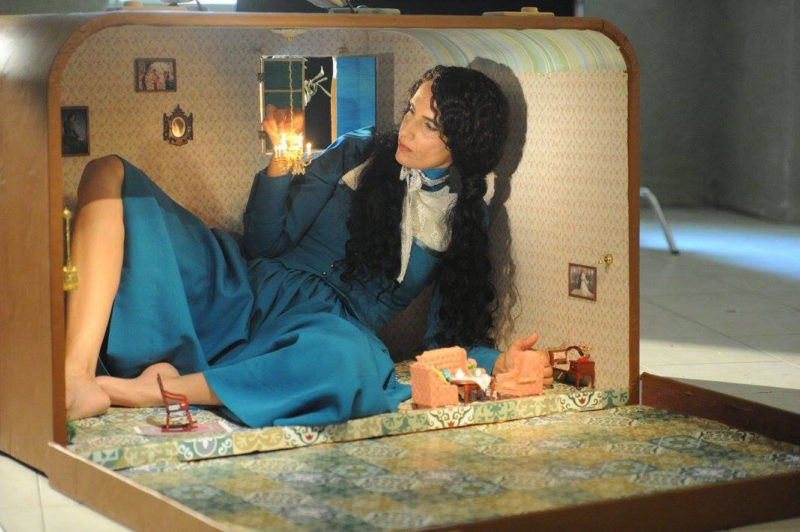

Although she didn’t exactly says so, Raida Adon, a self-defined Palestinian and Israeli artist and film and video actress, would probably not live in any other place, either. “We have Jews, Muslims, and Christians in the family,” she said. “I can’t choose one thing. But, I can’t say that I am completely Israeli either.” Adon’s studio is based in her Jaffa apartment, where a suitcase that she made, just big enough for her to perform in, occupies one corner of the salon. The piece, Strangeness, follows from an earlier video, Woman without a Home, where she is seen on camera dragging her bed across a snowy landscape near Mt. Hermon. “I was trying to find my homeland when I was doing this,” Adon said. “But no one knew that I was really sick. That it was personal.” Before shooting all of her videos, Adon paints a storyboard, sews all of the costumes, and makes the entire set.

Adon doesn’t yet have a gallery and wishes that she had one. “Maybe it’s because I’m both Palestinian and Israeli,” she said, “or maybe it’s because video art just doesn’t bring in money.” For the present, her studio is in the street. “We need to respect each other,” she said. “If you see people, you listen to people.”

There is no doubt that video artist Dor Guez knows how to listen and to do research. Drawing upon his cultural heritage, Palestinian-Christian on his mother’s side and Jewish Tunisian on his father’s, Guez focuses on the other in his video work. His ongoing project, The Sick Man of Europe, deals with the legacy (both historical and cultural) of the former Ottoman Empire. On view at The Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem in April was the third part in this series, The Composer, the story of an Armenian composer whose family was deported from their hometown during the Armenian genocide. Two earlier video projects, Watermelons Under the Bed (2010) and (Sa) Mira (2009) illuminate the Arab-Christian and Arab experiences. In (Sa) Mira, a Palestinian Hebrew University student speaks about being asked to change her name on the dinner receipt by her Israeli restaurant employer. The powerful video moves from what seems to be a lightly told anecdotal tale to one that reduces the speaker to tears. Why should she change her name from her birth name Samira to conceal her Palestinian identity? Why should she sign her checks with the Israeli name Mira? Two letters, Sa, speak to the pain of her greater divide.

More contemporary art, often with a political edge, can also be found beyond the stone walls in Jerusalem and the white stucco Bauhaus residences of Tel Aviv: in Petach Tikva, or Herzliya, or Ein Harod, and even in the Palestinian village of Umm El Fahem.

Citizens, an exhibit at the Petach Tikva Museum of Art, curated by Neta Gal-Azmon, explores the tension between states and citizens, and raises questions about freedom and the lack thereof. Prominent in the exhibit is Zac Hacmon’s T.A.Z. (Temporary Autonomous Zone) (2014), a recreation of a guard booth, slightly smaller than life-size to heighten the feeling of claustrophobia, that draws upon the artist’s own experience working as a security guard, a job many young Israelis took after finishing their military service. The booth is understood as both a refuge and a place of authority. Hacmon has installed a CCTV that screens all activities in the museum through the lenses of four security cameras and spectators are invited inside to become security guards themselves. “The booth, “Hacmon said, “is not something we study in architecture school. It is invisible.”

At the Herzliya Museum of Contemporary Art, In Her Footsteps, an exhibit of eight women artists, includes Michal Heiman’s AP—Artist Proof, Asylum (The Dress, 1955–2017). With its artistic lens turned inward, this introspective work includes installation, performance, video, sound, photographs, floor work, objects, documents, and archival display. While doing research in the book The Face of Madness: Hugh W. Diamond and the Origin of Psychiatric Photography, Heiman found her adolescent self in an image of a woman (Plate 34) who lived in a British asylum. She began taking multiple portraits of women, including herself, wearing a plaid dress that replicated the uniform of the residents in the institution. “I saw myself in the book, and I asked, ‘What does it mean to return to oneself?’ At the same time, I asked, ‘What does the right of return mean in Israel?’” Heiman believes that we have much to learn from this history. “Strategies of how to survive in the nineteenth century have many parallels with strategies of asylum seekers today.”

Over sixty thousand Palestinians live in the town of Umm El Fahem, located in Israel on the seam at the border of the West Bank. The town is home to the Umm El-Fahem gallery, a nonprofit space that director Said Abu Shakra hopes to turn into the first Palestinian Museum inside Israel. Shakra proudly shows off a model for the new museum, for which the Finance Office of the Israeli Government has secured about five million dollars, contingent on his raising matching funds. “No easy task,” Shakra said, “since his Arab brothers say, ‘You took money from the Israeli government; they will control you.’” Although the gallery is presently “a museum in a very small house,” he hopes that its twelve-year-long gestation period will soon be at an end. “Perhaps this year or next,” he said. Yael Reinharz, Artis executive director, added, “It is important that visitors to Israel meet Said to learn about his bold vision as well as the challenges of being an Arab-Palestinian gallery that is supported by the Israeli government and within the confines of the 1967 borders.”

Shakra believes that his gallery can help Jews “touch the Palestinian narrative, and create empathy and respect.” On view in April was the work of his brother, artist Farid Abu Shakra, and The Sea of Fire, an exhibit by Arab-Israeli photographer Ammar Younis. The show does not include pictures of either Intifada but rather several color images from Waste Bank (2013), documenting a garbage dump near the Palestinian village of Yata, and striking photos from Brides in White, a series focusing on the elderly women of Wadi Ara.

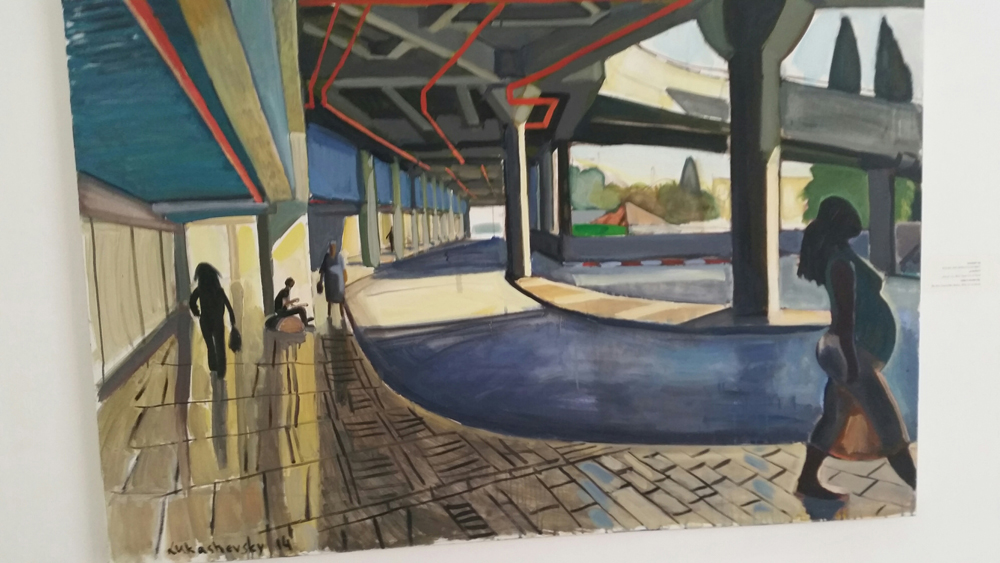

A half hour’s drive from Umm el Fahem is the Ein Harod Museum of Art, a Bauhaus-inspired building by architect Shmuel Bickels that infuses natural light throughout the galleries. Built in 1948 and holding the distinction of being the first museum in the country, it grew out of the collective’s ideology that their kibbutz would become a cultural center. Along with the museum, they established a theater, a book publishing enterprise, and a music center. Director Yaniv Shapira spoke of the museum’s extensive collection of Judaica, Jewish art, Israeli art, and kibbutz art. “For many years,” he said, “we tried to be an alternative to the main venues in the big museums.” Today Shapira describes the place as an art, cultural, educational, and social center for Arabs and Israelis. Owned by three kibbutzim, the museum struggles to fulfill its mission on modest finances. On view was Back to Life, an exhibit dedicated to the New Barbizon Group, five female Russian émigré artists who paint from observation. Shapira said that the show is “one of the most popular exhibits in Israel.” At the end of May, the entire museum was turned over to the Euphoria Project on the fiftieth anniversary of the Six-Day War (1967). “The war began the occupation and there will be five different exhibits dealing with this open wound,” Shapira said. “We will touch heavy issues.”

Chen Tamir sighs when she speaks of the current culture wars. Israeli arts institutions are now required to comply with regulations pushed by the right wing and imposed by the Ministry of Culture, headed by the controversial Miri Regev. If they do not exhibit their work or perform in the territories/settlements, their budget is cut 30 percent. If they do, their budget is only cut 2 percent. “Anyone advocating for boycott can now be penalized,” Tamir says, adding that “government funding that is in place is terribly managed.” The Al Ma’Mal Foundation, a nonprofit established “to promote, instigate, disseminate and create art” has solved their funding problems another way. Housed in a former tile factory in the Old City, the Foundation receives core funding from the Swedish Development Agency. “We’re in a cloud in Jerusalem,” director Aline Khoury said. “We don’t take funding from the Israeli government. We don’t agree with their politics.”

Established Israeli artist Sigalit Landau holds strong opinions on the current climate in the Israeli contemporary art world. For more than two decades, Landau’s work, in video, sculpture, and performance, poked and prodded at existing norms, sprinkling salt on the psychological, ecological, and often still-open physical wounds of Israeli life. In Barbed Hula (2000), the camera focused on her nude body, a Hula-Hoop made of barbed wire around her waist. With every move, intense pain. Five years later, in DeadSee, Landau filmed herself floating in the Dead Sea, surrounded by hundreds of watermelons (some open to reveal wound-like red flesh) that were joined by a rope to form a spiral. Pulling the rope unraveled the spiral.

Landau describes her art work as “bridge-building”: “In my [sub]conscious I search for new and vital materials for connecting the past with the future, the East with the West, and the private with the collective,” she said. And that is exactly what she has been doing over the past two years in her latest project, which involves designing a bridge that will float on the Dead Sea. At one time, she envisioned building a salt-encrusted bridge linking Israel and Jordan that would simultaneously call attention to the lowering of the sea’s waterline and to Israel and Jordan’s peaceful relations. With approvals hard to come by from Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority, her latest design calls for a bridge, fifty meters long, twenty-eight meters across, and four meters high, floating in the middle of the lake and accessible to swimmers and boaters.

Landau likes the fact that she is not dealing with a museum or a curator. She believes that museum boards and committees have grown in strength and that “people with charisma are not tolerated as much as they used to be in Israeli Institutions.” Always outspoken, Landau labels the boycott as “boring. You just don’t get invited,” she said. She’s not worried, though. Over the past two months, she has been working on five installations and a major book on her projects will be coming out in August.

Younger Israeli artists face the tensions in the contemporary art climate with hope and determination. Fatma Shanan Dery, a Druze painter, with a studio at the soon-to-be-torn-down Artport Collective, speaks of her upcoming exhibit at the Tel Aviv Museum in June. With paintings that resemble oriental rugs, she struggles to develop and grow in a traditional community. While most Druze live in Syria, some one hundred twenty thousand live in Israel. “For me, the issue always is, how do I create my own space? “ Roni Hajaj, an Israeli of Moroccan heritage, describes her style as completely spontaneous. “I often add found objects to the art works at the last minute, even on the day of the opening,” she said. Three woven mats with slabs of clay as pillows lie on the floor of her solo exhibit, A Foot, Tops, in the RAW ART Gallery.

In the outdoor café of The Diaghilev, a live art boutique hotel in Tel Aviv, Micha Ullman orders tea. At seventy-eight years of age, Ullman is considered by many to be one of Israel’s most prominent artists. He is currently at work on a piece for a new library in Jerusalem. All he will tell me is that it will be about “words.” Millions of people visit his memorial to the book burning in Berlin; an underground space with empty bookshelves viewed through glass from above.

Ullman says that he is an optimist but admits that the right wing worries him. In the last five years, aggression has changed both outside and inside the country. He sees the occupation as much more dangerous for the existence of Israel than the enemies that surround the country.

As a teenager, Ullman wanted to be a farmer, so it was no surprise that earth and digging entered his art. As a sculptor, more and more he became interested in the empty space that resulted from the digging—in the pit. “We sit seventy centimeters apart,” Ullman tells me. “Two pits. I am pushing air. You are pushing air. Speaking is the most beautiful music I know. In this music lies the solution.”

Another sip of tea, and Ullman adds a final thought, “I speak to my Arab friends. It opens the doors. You are not worth more or less than the person you are speaking to.”