Content Warning: This excerpt contains descriptions of sexual assault.

Early evening. We were in your car, at the end of your block, at a stop sign. The streets were empty. My window was open because I hated closed windows—probably because I thought my why drive if you can’t feel the wind attitude made me profound. We were sixteen.

I just needed to leave my house, you said.

With a few classmates, we’d been cramming for an exam about waves and optics and contemplating why our accomplished physics teacher taught at our poorly ranked public high school. Cost of living? Witness protection? He actually likes Sandusky? When we left, our classmates were writing formulas on their wrists with fine-point markers.

Let’s drive until we hit civilization, I said.

You stared straight ahead at something, it seemed, that couldn’t be seen.

Somewhere with a bookstore, I said, like a real bookstore. One with a poetry section that’s more than one shelf.

You squeezed the steering wheel and suddenly your pale knuckles looked cartoonish, like a badly rendered, unshaded drawing of knuckles. I barely glanced at your face. I sensed you were resisting tears.

You told me I was important to you. I told you I knew that, and you said, No, really, you’re the only one who understands me.

You turned, looked at me, then quickly looked away. I had never seen you cry before. I hadn’t seen many teenage boys cry, but I didn’t say that.

I know you understand this, you said. I just get so lonely.

This is probably my favorite memory of us.

I know you’re sad now, I said, but I promise this will be a happy memory someday. Us at this perfectly straight stop sign.

You nodded, and I wonder if I explained my observation, or if my observation was insightful enough to imply its metaphoric meaning, as in: let’s notice when things are right.

The memory stops there. If you were critiquing this, you might say, Come on, Jeannie, it’s a little too perfect, don’t you think? The memory stopping at a stop sign.

THERE ARE GAPS

I already predict failure.

I’m afraid he’ll say no, or even worse: ignore me. But why wouldn’t he agree to speak with me? He owes me that much.

I could disguise his identity, change his name.

Combing a naming dictionary for some rough translation of friend, I first land on Aldwin: old friend. I picture a knight, an eleventh-century Norman invader, a sorcerer in a fantasy novel, a president of a Martha’s Vineyard men’s club, a child of artfully tattooed parents. Between 1880 and 2016, the Social Security Administration recorded only 129 babies named Aldwin. My former friend’s pseudonym should be common, modern, unassuming. I want readers to know someone with the same name.

Phil means friend. But he’s not the Phil type. Phil orders everybody drinks. Phil shakes your hand, says, Call me Phil. Phil’s too casual, too laid back. My former friend may have slacked from one day into the next, but he wavered between anxious and depressed.

Philip, then? Philip contains friend. Friend of horses. But I doubt he ever touched a horse. He preferred the indoors, rarely straying from couch, desk, and bed. His white skin burned easily.

Forget name origins. What about the origins of words that are also names? Like nick. Some of nick’s obsolete meanings: reckoning, or account; slang for the vagina.

But I dated a Nick. In college, briefly, between boyfriends. I’d prefer that memories of Nick (him telling me: I could tell you weren’t very cultured when I met you, and How have you not heard of Broken Social Scene? and I don’t understand why you won’t sleep with me if you like me) not influence this project. Though I like the sound of nick. So, I want a monosyllabic word that works as a name and contains a k.

Mark, maybe? Its main definition: a boundary. And that’s what this is about: boundaries.

Perfect.

Mark, then.

Why should I protect Mark?

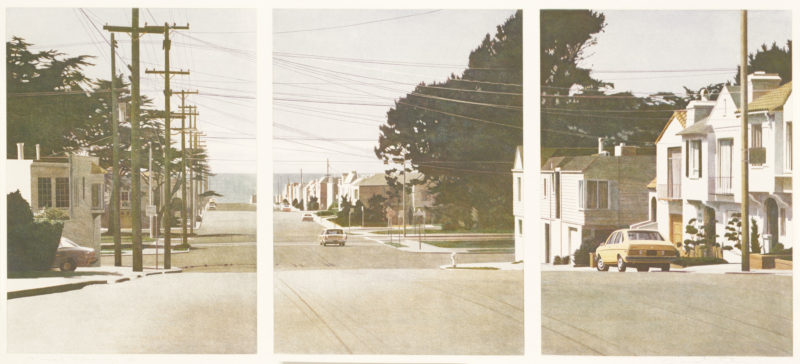

I enter his work address in Google Street View. Instead of his pale yellow office building on an industrial one-way street, I aim my view at the clouds and telephone wires. The wires don’t line up precisely. There are gaps of just sky.

Gaps between communication…

I should stop searching for metaphors.

Mark and I stopped speaking to one another in college. He was in Ohio, studying engineering. I was in Illinois, majoring in journalism.

He dropped out shortly after we last spoke, which is not to say I’m the reason, or that what happened between us is the reason.

But I hope it’s the reason, or rather: what he did to me—during winter break of our sophomore year—is, I hope, the reason.

I can’t forget: I was passed out.

Mark now manages a camera shop. I recently found an online forum where he answers questions about cameras. Someone asked if a blur in a photo can be good, and Mark replied: If the intent is to give an abstract rendering for some artistic reason, then it’s acceptable; when no such intent exists, it’s merely bad technique that has caused something that should be sharp to blur.

If he could photograph that night, would he blur it? Where would he blur it?

My memory is blurry. There are gaps.

But I know what he did, and he does too. The next day, or maybe a few days later, he apologized: I should not have done that to you. I am so sorry. It was not okay. Can you ever forgive me?

I said I could. I said I would. I told him to read J. D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, my favorite novel back then. I cringe at the memory.

He read it and told me it reminded him of us.

But no one in the book carries his drunk friend into a basement, takes off her clothes while she’s passed out, fingers her, masturbates over her while she cries, and tells her: It’s just a dream.

I’m so glad you liked the book, is what I said.

A year later, Mark dropped out of college.

He moved back home, tried therapy, became a mechanic—at least, this is what his dad told my mom. By then, our friendship had ended, though I doubt his parents and siblings knew why. Friends grow apart, is probably what they thought. As with many things after my dad died, I never told my mom.

Mark, according to LinkedIn, returned to college, earned a bachelor’s in interdisciplinary studies, and, several years later, a master’s in civil engineering.

When we were friends, I told him: Someday you’ll become a famous engineer. You’ll discover a formula so complicated that high school students will write it on their wrists before exams.

Every time I think about him, I feel pissed off and sad. I understand now why nostalgia, for hundreds of years, was considered a chronic mental illness.

I want to hate him, but I can’t.

IF HE SAYS NO

First, do I call or email?

If I call, do I call from a disguised number?

It’s too easy to ignore an email.

Do I tell him immediately why I’m calling? Or do I warm him up with small talk pleasantries? So, uh, how have you been?

What’s new?

I’m not flying to where he now lives.

But it is harder to say no in person.

I know where he works. A nine-minute drive from the airport. Only thirty-four minutes if I walk. And suddenly, I’m wondering, Would it be safe to walk? I consider arrival times.

Let’s say I confront Mark in person.

Let’s say I tell him, This is the only way I’ll forgive you.

I unforgave him. I forgot to update him.

My word processor says unforgave isn’t a word, suggests I make it unforgiven.

If he says no, I’ll do it anyway.

Why not unforgave, or unforgive?

Why do I need his permission, anyway? I never gave mine.

What would the book be without him?

Who would I be had I never known him?

I want to include him—because without him, the book will be: yet another story about yet another sexual assault.

Why do I assume yet another story about yet another sexual assault can’t be told? Or can’t be interesting?

I ask my editor what she thinks.

Either way, I want to work with you again, she says. But you might be right, unfortunately. The book will certainly stand out if you include him, but even without him, I still want to do it. It will just be a different book.

I hate that I feel dependent on him.

I need a script. No drifting off into accommodating his feelings.

If he says no, here’s what I’ll tell him: You are supposed to say that you’re sorry, that you will do this for me. That’s how this works.

Though that wouldn’t be a genuine apology. And he already apologized. And anyway, I don’t want another apology.

I want his consent.

IF HE SAYS YES

If he says yes, I won’t thank him.

I won’t tell him that everything is okay between us.

I won’t comfort him.

I am assuming he’ll need comforting.

Politeness isn’t needed.

You ruined everything, I’ll tell him. You realize that, right?

I can say everything.

I’ll ask him:

Do you still think about what happened?

Is it the reason you dropped out of college?

Did you ever tell anyone? A therapist, maybe?

How did you feel the next morning? The next month? The next year? Today?

Do you remember how I felt, or seemed to feel?

Did you ever miss me?

Has my contacting you upset you?

Have you dated anyone?

Have you done to anyone else what you did to me?

Do you know what your brother told me earlier that night?

He told me that I wasn’t as pretty as you and the other guys made me out to be. You want to know the fucked-up thing I thought after you did what you did? At least I’m pretty enough to assault.

What did you think of yourself back then?

What did you think of me?

Are you still in touch with friends from high school?

Why would you ruin what we had?

What are your favorite memories of us?

Is it messed up that I sort of want to see you? For so long, I believed that seeing you would break some rule: Boy sexually assaults girl. Girl stops speaking to boy.

Remember how we railed against boy-meets-girl movies? We could be so pretentious. We rolled our eyes at rom-coms.

I’ll tell him: I still have nightmares about you.

I MIGHT STOP FEELING ASHAMED

Reading about the legal considerations for memoirists, I almost laugh at the suggestion of securing consent.

I should ask him?

My partner, my friends, my therapist, they can suggest why Mark assaulted me. But their conjectures might diminish the urgency I feel about this project. They might transform the particulars of what happened into some stock instance of an already accepted theory in sociology or psychology or whatever. I want Mark’s why.

Had he been sober, would he have restrained himself?

How can I expect him to be honest about that?

Or even to know the answer?

I’m thirty-three years old, an assistant professor at a university outside Baltimore. I tell my creative nonfiction students not to ask for consent from anyone mentioned in their essays.

Wait, I tell my students, until you’ve settled into your writing.

But let’s say Mark grants consent and honestly answers all my questions. He undoubtedly will want his identity obscured. But if I blur it, I fictionalize—and so in my efforts to protect him, do I discredit myself?

This question, though—why include him?—interests me more than any question I could ask him—because it leads to an uncomfortable thought: My story isn’t interesting without him.

As a feminist and an artist, I’m ashamed that his voice seems necessary. I teach college students how to explore their stories artfully. I’d never tell a student that her personal essay about sexual assault would be more interesting with the perpetrator’s perspective. Until now, I hadn’t considered that point of view. And every semester I read at least five student essays about rape. These students are always women, and these women often ask some variation of: What counts as sexual assault?

Sometimes they ask me if they’ve been raped.

Sometimes, knowing the answer, they make excuses for the man: he was drunk, he was sad, he had low confidence.

Their rapists are never strangers in the bushes or alleys. Their rapists are their friends, their boyfriends, their boyfriends’ friends, their bosses, their relatives, their teachers.

Their excuses frustrate me, but I understand.

Here I am, trying to render the Mark I knew before that night.

When Mark knew me, I edited the high school newspaper, then majored in journalism on full scholarship at Northwestern, and then interned for a business reporter at the New York Times Chicago bureau, where I researched cube-shaped Japanese watermelons and Europe’s stance on genetically altered crops. I desperately wanted to become a journalist—and whenever I doubted my abilities, Mark would remind me that I’d earned a full ride to a top journalism school.

But one month after I started college, my dad died—and I became increasingly obsessed with a deathbed promise: that someday I’d write a book for him. He was under so much morphine I doubt he even heard me. But by junior year, my promise led me to switch majors, from journalism to creative writing. I’d either write a novel for him, or I’d write him a book of poetry. Memoirs, I assumed, belonged to celebrities and politicians. But then, fifteen years after he died, I published a memoir for him, about him, about my love for him. This genre felt right. I wanted readers to know: the man you’re reading about, he was real and I loved him. He was sixty-one and retired when I was born, but throughout my childhood he didn’t seem old, not to me. We’d spend entire days together, swimming, riding bikes, feeding birds by the lake. Not until I became a teenager did I notice his worsening health. He was bedridden the last year of his life. Doctors said there were so many things wrong with him. His death certificate lists throat cancer. While I never expected my first book to diminish my grief, I think it did. I rarely dream about him anymore, and I’m okay with that. Maybe this book will end my nightmares about Mark.

But that’s not why I’m writing this.

I’m writing this because I want to interview Mark, interrogate Mark, confirm that Mark feels terrible—because if he does feel terrible, then our friendship mattered to him. Also, I want him to call the assault significant—because if he does, I might stop feeling ashamed about the occasional flashbacks and nightmares. Sometimes I question whether my feelings are too big for the crime. I often remind myself, He only used his fingers. Sure, I could censor my antiquated, patriarchal logic (sexual assault only matters if the man says it matters), but I want to be honest here—because I doubt I’m the only woman sexually assaulted by a friend and confused about her feelings.

*

Excerpted from Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl, published by Tin House Books. Copyright © 2019 by Jeannie Vanasco.