Facts, Day One:

1. There is a lesion in her brain.

2. It is 3 millimeters in diameter.

3. It is behind her posterior pituitary lobe.

4. The pituitary is called the master gland. It controls so much of the body.

5. The lesion has hemorrhaged.

6. The hemorrhage has not reached the optic chiasm.

7. It is probably nothing to worry about.

But it didn’t really start with Day One. Day One was actually Day Nine. Or maybe Day Forty-five. But we call it Day One, because everything started so slowly—with gaps and holes and absences more than a presence of anything. Getting sick wasn’t an imposition of anything new; it was the beginning of a lack.

First, a lack of words. Sitting in a seminar, looking left and looking right. How do people talk? Do people know what they’re going to say before they start? Do the sentences come out as they’re formed, or are they formed first? When people begin to talk, how do they know what they’re going to say?

The class was on the history of life writing. (Convenient, no?) So, she tried, mimicking:

“This idea that narrative constructs life as we live it, that it isn’t—

“It isn’t….

“This idea of construction, it’s like you can’t write what you are living as you are living it,

And again:

“But I’m trying to say, what I’m trying

“I think…

“Here, with what McCarthy argues— what was important with—letters

“And diaries—the functionality, the functionality turns into—it’s—where it’s—

“Different—with a different from before, from earlier—where

“I, does anyone get what I’m—say—trying to—

“I haven’t slept in a while

“I’m sorry

“This isn’t—

“This shouldn’t

“This shouldn’t be coming out like this.”

This is how it started: Falling into the spaces between words, between ideas, between sentences. An infinite elbowing out of time, and time and space between. Gaps upon gaps upon gaps upon gaps. Reaching for the next sentence and then, the next word just… fell.

She is a graduate student. She is thirty. She is smart. She’s been around some of the typical blocks former New Yorkers go around, and nothing that bad has ever happened, and so she tells herself that she forgets the words because she hasn’t slept. Because she’s in school. Because she’s stressed about her qualifying exams, the ones that will transform her from “student” to “candidate” (ever growing, ever upwards). And because everyone forgets words; that’s what the neurologist will say when she can’t memorize the given sequence of ball, table, chair: “It’s the stress of trying to remember that is making you forget.”

How to explain that she thought the gaps would fill themselves in, would right themselves? It had happened before, worries cropping up and then resolving. Being tired, but everyone was tired. Being dizzy, but everyone got dizzy. Forgetting words, but all the grad students forgot the names of the authors they—we—were supposed to have on the tips of their—our—tongues. Forgetting and getting mixed up and being tired, it all fell into the category of stress, or graduate school, or the long bike ride over the weekend, or the yoga class that made her sweat. Waking up feeling like a train had hit her: that was how it was to be thirty, right? And of course the excuse that she just hadn’t slept wasn’t just a story—it was also the truth. (She wasn’t sleeping.) A round little ball of truth, a refuge of fact, an island that would prove, later, to be just one part of a long chain of islands.

And besides, it’s almost always nothing. The friends, all of them, a chorus of “I’m sure it’s nothing to worry about,” “I’m sure you’ll be fine,” “My cousin had a thing and he was fine,” the reassurances all reaching forward into when she would turn out to be fine, but never sideways, laterally, into the present moment.

There have to be other facts: How did she know something was wrong? Later, somewhere in the second part of the third section of the middle, people will ask that. And then, even later—or maybe it was earlier—they will ask, “How didn’t you know something was wrong?”

On a Tuesday, she fainted. She was standing in the hallway at home, trying to talk, and then the world went black, the blackness rose into her eyes and she slumped, fell, was caught and slapped awake. Still this was nothing, just a random thing. The night before she had vomited, suddenly, but sometimes people vomit. And that morning she had woken up and vomited again, made ginger tea to calm her stomach and still, the roiling nausea. But that was just exhaustion. Still, on a recommendation, she went to urgent care, just in case. Skeptically, the nurse gave her an EKG.

“Surprised by the results,” the report said. “The patient exhibits the rhythm associated with Wolff-Parkinson-White.”

At least, that’s what she remembers it saying. She has kept hundreds of other pages like this, the ones that come later and say other things, but not this first one.

It’s significant that the nurse was surprised. Surprised to find evidence of something other than stress, or grad school, or being a young woman in 2013. The nurse recommended a cardiac follow-up within two days. “Make the appointment now, when you leave the clinic,” the nurse said. “Tell them it’s urgent.”

From nothing to urgent in the 2.5 seconds it took to hold her breath and print the EKG. From nothing to something: “Urgent,” “Cardiology follow-up.” These words meant nothing to her. Couldn’t mean anything. She didn’t have the language for this yet.

She made the call and then, normal life—but life that knew it included an appointment, a follow-up. Not within two days, but within six.

“We are starting to think there’s nothing wrong with you,” they said.

And then, those two urgent days later, she tried to stand up, and couldn’t. She went to the emergency room, gave blood and was given fluids. She was admitted. (Something was admitted to.) And for six days in the hospital they searched and found nothing. Meanwhile: Dry mouth. Racing heart. Disorientation.

“Do you want to eat lunch?”

“I don’t understand the question.”

The patient exhibited signs of distress.

The patient exhibited conviction that something was wrong.

The patient could not follow a conversation between more than two people.

She gave blood every twenty-four hours, every four hours, every hour.

She couldn’t sit up by herself.

She couldn’t walk down the hall.

She couldn’t get herself to the bathroom.

The world shimmered.

She was sick enough to, suddenly, be overtaken.

Her body became a mystery. (But what about her mind?)

She had a CT scan of her chest, an echocardiogram of her heart, telemetry on its rhythm.

“Your heart is flawless,” they said.

“Your lungs are clear,” they said.

“Your blood is negative for pheochromocytoma,” they said.

“We are starting to think there’s nothing wrong with you,” they said.

(But what about her mind?)

So it started slowly. And later, she saw that the slowness was what made her realize it had started.

The story: Cerebral graduate student interested in issues of life writing and narrative develops brain lesion that, though it is not directly on them, affects language centers, and she cannot find a way to write about nor narrate her way out of it. It’s a bit on the nose, she imagines people saying. I just don’t know if I find this believable. Maybe this part is too extreme? Go subtler.

Let’s meet the character. I was thirty years old. I’m thirty-three now. (It’s over; it ends.) I am five-foot-five but think I’m five-foot-six, with shoulder-length blonde hair that is sort of brown. When I first wrote these words, I was dressed like this: a navy blue t-shirt, green cargo pants, seersucker-printed boat shoes, a tan belt. Now, I’m dressed like this: jeans, a button-down shirt. While all of this was happening, I lived in Berkeley. I taught and wrote about architecture. I was in a relationship that I hoped was teaching me a lot about life, even as I realized it might not be. (Now: I’m married, to someone else.) Before that, I lived in New York City. I wrote two books before I turned twenty-eight, lushly photographed architectural monographs. There were times I thought to myself that I was sort of a star, or that I could be. Would be. Before my first book came out, my mentor said, “Fuck, I’m in love with your brain.” After the second book came out, my editor said, “And now we just wait to see what your big brain comes up with next.” Somewhere between the first book and the second book, my father had said, “We all just keep waiting for that big brain of yours.”

(But what about her mind?)

In the hospital, the infinite expanse of that present moment, she doesn’t have that armor. No one thinks she’s especially bright or promising. She wears only a gown that opens in the back, and when she stands up and walks to the bathroom everyone can see. She has those hospital socks with the sticky little dots that grab onto the floor so she doesn’t slip. She hasn’t showered in a week, though there was that sponge bath, where the nurse—whose name, now, feels like it must have been Rosario even though she knows it wasn’t—washed her hair with a special foam. In the hospital, the one thing she always prized, that always saved her—her brain—is the thing that isn’t working.

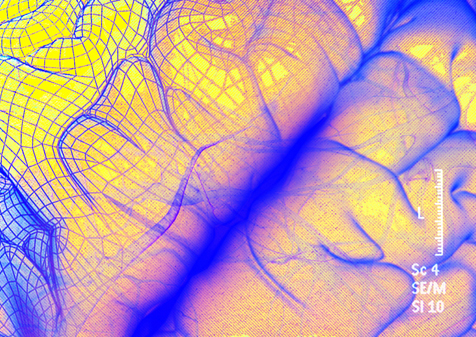

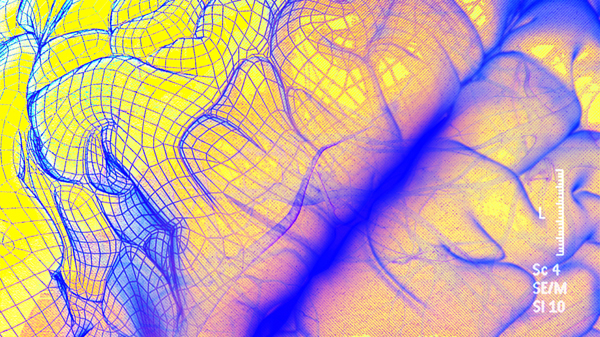

Thirst, disorientation, nausea, vomiting: These are brain symptoms. And so, finally, there is a brain scan. What it reveals is a tumor, maybe. A cyst, maybe.

She doesn’t know enough to ask if it’s benign or malignant. She doesn’t yet know that this will start to be the only question that can ever matter, and one over which she has no control.

Life, in the middle, becomes a process of waiting for the next appointment, the next piece of information, the next commentary on the latest piece of information. Like her tumor marker, a thing she hadn’t known existed before hers was drawn, measured, before she saw the number highlighted in yellow on a doctor’s screen, and then at the bottom of the screen an explanation: “Yellow = Abnormal/Panic.” Her marker was alpha feto-protein, expressed only when a tumor was present. Expressed only when abnormal tissue was present.

Testing it was a routine draw, a gold-cap tube or a green-cap tube, and at first maybe the elevation had been an accident or a false positive, but then it was tested again and again and again and every time it was higher. At home after one test, chopping onions, she cuts her finger and watches the impossibly dark blood slide down, knowing that every droplet contains the marker. How big is the marker? Where is it? If she elevates her hand, will she elevate the tumor?

Words change in meaning. Yes to: an elevated experience, an elevated level of interest. An elevated train. But an elevated marker? Please go down. Please go away.

The marker was enough to warrant a biopsy. The marker was enough to make a neurosurgeon want to take out his drapes and his scalpels and his drills and his glue. The marker was enough that the lesion was now suspicious—more than suspicious—and the word cancer was never said but the words “a rough treatment” were, and the words “chemotherapy” and “radiation” were used and it was so fast, so very very fast, from not worrying and everything is going to be fine to, suddenly, everything being wrong.

From the official post-surgical report, dictated but not read:

The patient was draped in the usual manner, placed in a semi-sitting fashion.

The bone separating the nose from the sphenoid sinus was shattered.

Glued back together.

She waits and reads about pituitary stalk thickening, about the hypothalamic axis, about the symptoms of brain cancer.

They went in through the nose, through the sinus cavity, around the back of the pituitary, where the lesion, the mass, the maybe-tumor, was nestled. They drained and removed that, an almost—full resection—the word is re-sect, seeming so incomplete. A re-section rather than a removal, because they couldn’t get the whole thing, but they got what they could, and also they took her brain: an inch by an inch by an inch, pinkish-gray in color, submitted in cassettes to pathology.

The tumor, maybe, was declared to be a cyst, definitely. But there is never enough information. There is another suspicious location, also in the brain. Maybe that’s where the marker comes from. And so. Watchful waiting. Time begins to stretch, punctuated with follow-ups (post-surgery looks good) and then another follow-up (further changes post-operatively) and then pain becomes an issue, the management of pain, and then the information becomes clouded, and also the only solace. She checks and re-checks the graph that charts her tumor marker. Where is it coming from? “And then, one day, the tumor will just pop up,” she remembers her surgeon saying, before he took her brain. She waits and reads about pituitary stalk thickening, about the hypothalamic axis, about the symptoms of brain cancer. But the information can never be a solace, because it doesn’t add up. There’s no more getting out of the woods. There’s just more woods.

She is in a university clinic, lying on a gurney, head propped on a cold hard pillow. She is having her vitals taken. Her heart rate is 92 when lying down and 135 when standing up. She knows this means she has orthostatic intolerance, that she is severely dehydrated. Her body cannot process the gallons of water she needs to drink, and now she needs IV fluids. (It’s the axis.) The doctor comes in and asks how many liters of saline she needs today. She last saw him on Tuesday, now it is Friday. The nurse tries to put the needle in her vein, but they are so scarred and collapsed from years of this that he can’t manage. She clenches her fists and then releases, like a pro. Still it doesn’t work. So she runs hot water over her hands until the tiny veins on the surface begin to pop up and be seen. It hurts. It almost isn’t worth saying so.

She is waiting for it to become a story, willing it to be.

In the New Yorker, Oliver Sacks wrote about Spalding Gray, how Spalding used his own material—his life experiences—to create his work. And how—maybe—Spalding got confused, started living his life so that he could get material. Then how Spalding was in a car accident and his brain was injured and how maybe—probably, definitely, definitively—that’s why he jumped off the Staten Island Ferry years later, drowning, on purpose. Spalding used his life as his work and then his work as his life and then he hit the limits of his own experience. It couldn’t be a story anymore.

She thinks about these two writers she loves and wonders: is all of this a test? She’s always lived by stories and narrative, everything in the spinning and the telling. Suddenly all she can do is tell the parts she can see, and tell them over and over and over again.

Later, when she can’t read anything except medical books and journals, saturating herself in a language that held her life in its hands for so long—in words like “indicate” and “suspicious for” and “differential includes” and “likely” and “probably”—she reads Oliver Sacks’s memoir, On The Move, and is stunned by his humanity, by the way he speaks about his patients—and by the pictures of him, sitting with a patient, unguarded, not defensive. And then at the end, he closes with this passage, and it is as though he has, from the beyond, understood her. His language, here, becomes her medicine, more potent than any pill, any injection, any drip.

“I am a storyteller, for better and for worse,” he writes. “I suspect that a feeling for stories, for narrative, is a universal human disposition, going with our powers of language, consciousness of self, and autobiographical memory.” And: “The act of writing, when it goes well, gives me a pleasure, a joy, unlike any other. It takes me to another place—irrespective of my subject—where I am totally absorbed and oblivious to distracting thoughts, worries, preoccupations, or indeed the passage of time.”

And with that comes permission for her own language to become her medicine. For the turning of these events into a story, a narrative, through the use of her own autobiographical memory—while it has not saved her, it has given her life.

For now, it can help give her story a clearer shape. Part of her believes that once this particular narrative has found a conclusion, once she has told the story, the pain will be over, too. So many books written by cancer survivors: “I remember the day I got the diagnosis. It was the worst day of my life.” You know they’ve survived because they’ve written the book.

So she turns it into work. She writes. She edits what she has written. She turns in a story for a fiction class and everyone knows it isn’t fiction. She revises it according to the readers’ feedback, then re-submits. She lets the writing sit for a while and then asks her professor what he thinks about the pacing. “I don’t think it feels too rushed,” he says, but to her it still feels too compacted and squeezed, like there isn’t any air in the piece at all. And so she lets it lie while she figures out what it would look like to add air, what it would mean to have breathing room.

She used to have a sense of the mind as infinitely expanding, neural networks that could be filled and refilled again and again. During her first week of graduate school, she went deep into the library’s main stacks and looked at the rows and rows of books, four floors of them. One entire section of shelves devoted solely to Henry James, and to what people had thought about Henry James. And she cried a little, because she could never read all of those books, because the knowledge of the world would remain elusive, no matter how hard she tried or how much she read.

Facts, Day 1,066:

1. She never had brain cancer.

2. She has 1x1x1-inch less brain.

3. The place where the lesion was will heal.

4. The place where the lesion was will never heal.

5. There is always so much to worry about.

She lost a piece of her brain and will never get it back. Even though the hole has been filled in—every day that she can’t remember a character from a novel or from Scandal, every day that she tries to justify her aversion to stringing words and sentences together from A to B to C to D, to explaining why her perspective drifts from you to her to past to present to me to I, is a day she is reminded that everything has changed. When she can’t remember what happened yesterday, or what she had for dinner last Saturday night, it’s no longer a sign of exhaustion, or stress, or excess. It’s a sign that something is wrong, or could be.

As a child, there was a moment I realized I would never become an Olympic diver. It wasn’t that I even really wanted to be an Olympic diver, but still I remember the moment. Watching a TV show about how the divers trained; it was all gymnastics, all on the ground. They didn’t even approach the water until they had mastered the jumps, the somersaults, all the ways of launching themselves into the air. And they were all so young when they started, younger than I was then, and so I knew it was too late. I had never before had the idea of it being too late for something, and suddenly here it was. It was too late for me. And so it didn’t matter how hard I might have wanted to start trying or how much latent talent I might have, buried in me like a secret. I could practice and jump and swim and dive, but I would never be one of those girls, and then one of those women, who flip backward off of a three-story diving board and land, perfect ten, in the water. It was too late; there wasn’t enough time.

Instead, I kept going through the door that was open: reading and reading, always hungering for more and more words. Now I read to know about the history of the National Cancer Institute; to know how patients decide and how doctors think; to know how Lisa Sanders became the doctor she is. I want to know how doctors are trained. I want to read words like cannula and chemotherapy and vincristine and rituximab and radical mastectomy and right ovarian cystectomy and intracranial germinoma, and let them wash over and into me, feeding me, soothing me, keeping me company. They let me know that there are others with thickened pituitary stalks, others who know what a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is (and a bilateral one, too). And they show me words I didn’t yet know, unfolding past the point where I can grasp or even see them.

I miss the complete submission to information, to overwhelm.

And then, just as suddenly as I was worse, I am better. I am given a diagnosis no one expected, of a rare and multi-system disease, that could or could not be the cause for the marker, for the cyst, for everything else that happened. A follow-up brain MRI shows a non-thickened pituitary stalk (“I don’t know what happened,” my doctor says), and my brain, eventually, rights itself. I can absorb water; nutrients. It has been over two years since I needed an IV saline infusion.

As soon as I am well, I want to give back. I dwell on the idea that I need to report from the edge, to help the next person. (but where does that come from, if not a desire to say I am no longer there?) I think, briefly, about going to medical school. I know that narrative—from patient to healing the sick—and I think about what I could do, with everything I know.

And yet I know nothing. And doctors know nothing. And isn’t this just bravado, wanting the sickness to be over and the healing to begin? I don’t want to wait in the in-between, don’t want that landscape that used to be so tiny to swell into the vast expanse of all possibilities once again being possible. There is safety in these tiny rhythms, in full sublimation to the hospital, to its crushing busyness. It’s not that I want to help, I realize. It’s that I miss the complete submission to information, to overwhelm. I miss the complete sublimation to a particular language, the language of illness, and that is why I want to go to medical school, and that is why I do not. That is why, instead, I write.

That language is a language I learned by watching myself suffer: watching my arms be pierced again and again and again by needles, butterflies, cannulas. (I know that word now.) By watching my body be infused with radioactive isotopes, watching myself raise my arms above my head as I am pushed into a scanning machine, the third of the year. By watching myself try to explain to a doctor that I couldn’t remember these words: Ball. Table. Chair.

I read a book written by a doctor just before he died. It’s a book lots of people are reading. The title of it seems so florid, and yet as I read and read and read, of his life’s tension between doctoring and literature, between deciding if he should spend his last days in the operating room or in the chair, writing, I know that I belong in only one of those places. Writing is still the only way I know to make sense of things, or at least to try. For years, I was a top in motion, spinning through doctors’ offices and surgical rooms and pre-anesthesia consults and post-anesthesia care units. And now? Now is the after, the after all of it, and I look everywhere for solid ground, and everywhere I turn the facts of my life are liquid.

“I’ve been gone for years,” I say to an art historian, who just wants to show me how the room setup works, so I can come back, so I can teach again, so I can start to make meaning out of all that has happened. “Research?” he asks. “No, dealing with mortality,” I say. Still so abstract. “Not yours, at least,” he says. And I say, “No, mine.”

As I was living it, my experience wasn’t one that had an arc. I couldn’t see the end from the beginning, or from the middle. What happened was that everything was going in one direction (death) and then suddenly it went in another (life) and I am still in the in-between. And all of it is the in-between, between one fact and the next fact. I swing through the vines of my days, between an assignment and a sentence, between knowing one fact about my body and knowing another.

There is a difference between believing that I could die at any moment and knowing that I could have died. And in that difference there is no ending. There is no catharsis. There is simply the sorrow and the grief and the ineffable beauty of knowing what it is to feel the end approach, to welcome its dark abyss, and then, so quickly, to have it swerve.