Fifteen minutes past the eastern edge of Mosul, on a day in early February, we come to a three-way intersection that, like much of the landscape, could be a stage set for apocalypse. War is sometimes cruelest when it keeps a semblance of what came before—homes not utterly destroyed, but roofs collapsed in a way as to make nothing worth saving. It is this incomplete destruction that mocks you, and it’s everywhere. The cleanup would be easier had everything been reduced to dust. Roads are inaccessible, save for main arteries cleared for the business of war. The chance that you’ll walk into that house with the caved-in façade and step on a mine or trip a wire bomb is not as high as you fear. But the reality is that it could happen and it sometimes does. There are dead men, enemy combatants, in some of these places and no one is going to get to them any time soon. Other priorities call. To begin with, attending to the flux of refugees who have settled in various camps in northern Iraq over the past three years. Some have been living an hour’s drive from their homes, others have come from Syria, where the scale of ruin dwarfs the imagination.

Alongside the three-way intersection you will find the best olives in all of Iraq, they say. Lined up next to the casks filled with olives are also dozens of barrels of pickled fruits and vegetables. The work of bringing all this here and taking it back to… where? seems extraordinarily difficult under the circumstances. When I ask what happens with the olives and pickles at night, when, I assume, everyone leaves for whatever place might serve as a home at this point, they say that they cover them, leave them, and come back in the morning. This seems reasonable and absurd. Which is how the photographer, Baroj, sees it too. His stoic stare travels the length of the road to where a broken city, Mosul, begins. From an earlier interview he’d given in an Iranian journal, I find out that as a Kurdish child refugee himself, some forty years ago, when Saddam was pounding this very geography, he watched as first one of his sisters then another committed suicide through self-immolation. I ask him what he thinks nowadays, standing here four decades on, taking photographs of more refugees, more ruins.

“I think that every day that we live is a day stolen from death.”

In the surrounding camps his lens follows the children and the old. The vulnerable. It’s as if by capturing them he is also lending them protection. They’ve been seen; they are here. In the same Iranian journal interview, Baroj also talks about moving from Iran to Sweden and ultimately back to his native Kurdistan. In Sweden the photographer spent ten years working in an old-age home, where death was a business. He wrote, in Persian, a collection of short stories based on his experiences: We Are Here.

“We are here” is an unsung refrain that echoes in the refugee camps across Kurdistan. On the day we visit Khizr camp, in the winter of 2017, there is actually a sense of movement. Everything with this war has been hurried. ISIS coming, ISIS winning, ISIS losing, ISIS leaving. It’s a dirty war—as if any wars are clean—and so even inside the camps you don’t, as a visitor, dare wander off on your own. ISIS has spies in the camp, just as the camp has spies within ISIS. It is like a video game. But all this is too real. With the gradual “liberation” of Mosul, many of the inhabitants of this particular camp have packed up to leave. What they are leaving to, no one knows. There’s no enduring joy past that first feeling of deliverance. Because, unlike what TV news portrays of those liberated, very soon comes the recollection that wars are permanent around here. Just ask the photographer. Who’ll come after ISIS? This is the sort of language you hear in and out of the camps. It is a weariness that eats at everyone, so that when you see a groom at Khizr camp getting a haircut, you wish him good luck in the life ahead without the least bit of sarcasm.

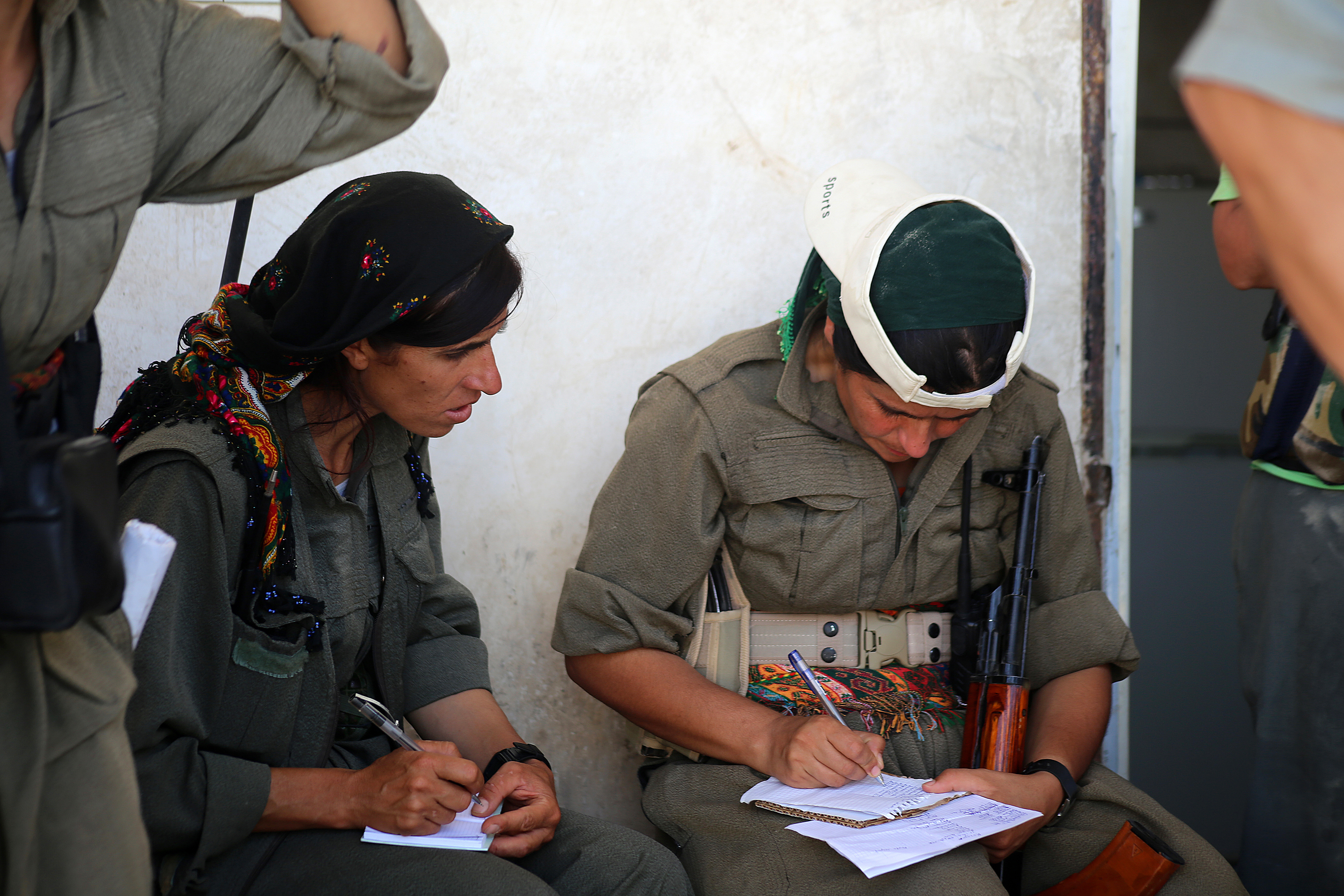

There are Kurds, Arabs, and the colossally persecuted people of the Yezidi sect, whose syncretic faith combines aspects of the Abrahamic religions with Zoroastrianism, in these photographs. There are also Peshmerga Kurdish fighters at the threshold of taking back a town. One of the images especially haunts me: a young fighter with a prosthetic hand, deep in thought before battle. The viewer takes for granted that the man lost the limb in some other fight, not too far away, not too long ago. But he is here, cradling his weapon with a sureness that must come from years of habit. The pinkie finger of the hand is wrapped in what looks like black electrical tape. A wound he can live with. Another day stolen from death. The photographer zooms in.

—Salar Abdoh for Guernica