Lead singers and difficult personalities might as well be synonyms. The frontman of the Baltimore-based hardcore band Hatebeak, Waldo, is no exception. With a blistering sound that challenges even the most sturdy of listeners, this is perhaps unsurprising, but it is Waldo’s austere lifestyle, in addition to the group’s provocative music, that have earned Hatebeak a cult following among the hardcore music community. While Hatebeak is known for pushing the limits of hardcore music in ways that seem to both mock and ridicule, they nevertheless take their art quite seriously. Waldo refuses to wear clothing or perform live, and confines himself to a strict diet of nuts and seeds. To some, his vocals are a series of incomprehensible shrieks occasionally interspersed with inane non-sequiturs, while others view Waldo and his musical endeavors more sympathetically. After all, Waldo is a Congolese grey parrot.

For many people, hardcore music is esoteric at best, alarmingly unpleasant at worst. But for those who produce, perform and listen to it, hardcore music has long been an outlet not only for extreme emotions, but also extreme political ideas. On one hand, right-wing political groups, including white nationalists and neo-Nazis, have a history of using heavy music as a tool to spread their ideology. This is one issue, in particular, that some hardcore groups are fighting back against with explicitly anti-fascist music, representing a central tension in the hardcore music scene. On the opposite side of the political spectrum, hardcore music has become a means of grappling with the existential realities of climate change and environmental destruction—a reverberant tool for navigating the dark, uncertain waters of the Anthropocene.

Decades before contemporary movements such as the Extinction Rebellion mainstreamed the ideas of a more radical eco-politics, a sub-set of hardcore musicians produced a sonic platform for broadcasting a more apocalyptic environmental message: the earth was dying, humans were the cause—wake up. In this sense, modern-day anxieties over global climate change and environmental destruction were long presaged by this fringe genre of music, which set the tone for the more desperate, existential political struggles that would grow in the wake of climate crisis after climate crisis. Perhaps by the nature of the music itself, challenging though it is, hardcore music has long proved a capable artistic medium with hardcore musicians lending their double bass-drums and seven-string guitars to musical treatises on subjects spanning ecofeminism and environmental justice. This political engagement is artistic as well as practiced, with many of these bands not only discussing pertinent environmental issues such as climate change, as in Gojira’s 2018 release “Global Warming,” but also actively participating in public activism and promoting various environmental causes in their day-to-day lives. Eco-hardcore music and bands like Hatebeak are interested in what lies beyond humanity’s ability to produce and understand. This notion of post-humanism—a critique of humanity that lies in understanding the world beyond a human perspective—looms over the genre. The post-humanist stance provides both a vantage point through which these artists level their critiques against humanity as well as a lens for understanding this music and the politics that manifest within it.

Dispersing with the niceties of political discourse, eco-hardcore music is both an extreme form of artistic satire, pushing social sensibilities to their limit, and a political performance, exposing the violence and hypocrisy latent within those sensibilities. They strike tones of catharsis, anger and despair with sometimes frenetic, sometimes plodding drums, distorted guitar and vocals that are screamed, yelled, and growled rather than sung. This music is an ethical critique of contemporary society, leveraging heavy music as a check on our collective conscience.

The foundations of hardcore music lie in the punk-rock bands of the 1970s and 1980s. Many of these groups often aligned themselves with anti-establishment ideas, writing music that took aim at the capitalist cultures of the United States and the United Kingdom. The Sex Pistols satirized the English state and monarchy with songs like “Anarchy in the UK” and “God Save the Queen,” while The Clash made their socialist sympathies evident with albums like Sandinista! (1980) and Combat Rock (1982). Following their lead, Black Flag, Social Distortion, Bad Religion, and Aus-Rotten then embraced radical political ideas in their music, wrapping their beliefs in the dissonant fuzz of too-loud electric guitars and tube amps. Aus-Rotten was particularly vocal about their anti-fascist, left-wing commitments, famously declaring that “People are not expendable, government is.” Many groups also aligned themselves with social justice movements. Groups such as Suicidal Tendencies, Bad Brains and the Dead Kennedys produced Afropunk music rooted in anarchist philosophy as well as anti-imperialism, anti-racism, and black liberation. Women’s liberation and LGBTQ rights also found a home within the hardcore music scene, with influential bands including Tribe 8, The Third Sex and Nervous Gender. Laura Jane Grace, a founding member of Against Me!, among the most successful contemporary punk groups, came out in 2012 as a transgender woman and has since made her experiences with gender dysphoria a theme for two studio albums. These political commitments remain alive and well today in hardcore music, contributing to a dynamic music scene that can be progressive and inclusive even if its music is not necessarily too welcoming.

The environmental movement occupies its own sub-genre within radical hardcore music. Known as “eco-hardcore,” such music emerged in the 1990s as a response to darkening realities of ecological degradation, climate change and the increasingly popular notion of the Anthropocene. By this time, the political optimism of the early environmental movement had been tempered by decades of political indifference. Environmental politics had become increasingly radicalized over the years as ecological crises multiplied and magnified. Reflecting this radicalization, much of this early eco-hardcore music was both visually and lyrically violent and anti-social, upending stereotypes of liberal, hippie environmentalists. Live performances were visceral, physical experiences with music that mimicked the increasingly panicked state of their political and environmental concerns. By reproducing and parodying the violence against and destruction of the environment, eco-hardcore musicians demonstrated how deadly serious they were about their politics and how dire the environmental situation had become. The time for polite discourse was over; radical, revolutionary, even violent action was needed to save the planet. This shift might seem abrupt, but its seeds in left-wing politics extended back to the politically tumultuous years of the 1960s, despite all the flowers and free love on the surface. As the decades wore on and the detritus of global climate change began to accumulate, the radical environmentalist message of eco-hardcore music has become increasingly prescient and, unfortunately, increasingly relevant.

Eco-hardcore music began with bands like Polluted Inheritance, whose 1992 album Ecocide married the power, aggression, and anger of hardcore music with an apocalyptic vision of modern industrial society’s environmental destruction. As sociology professor Ross Haenfler describes in his book Straight Edge, bands such as Earth Crises soon followed Polluted Inheritance’s lead, broadcasting their vegan lifestyles as part of their endorsement of radical environmentalism. These groups’ music is a blunt rejection of the social, political and economic systems that are complicit in environmental destruction and the oppression of animals. In 2015, Earth Crises teamed up with fellow eco-hardcore band Liberator to release a split album and comic book titled Salvation of Innocents, which follows the illegal efforts of a group of animal liberation activists.

The combination of intense music alongside earnest political commitments and gentle lifestyles produce an aesthetic dissonance that makes it harder to dismiss hardcore music and musicians as thoughtless, violent, and pointlessly aggressive. While it might be surprising to many listeners, this dissonance enables both a personal and a performed politics in which one can both live according to certain political ideals and express those ideals and their urgency.

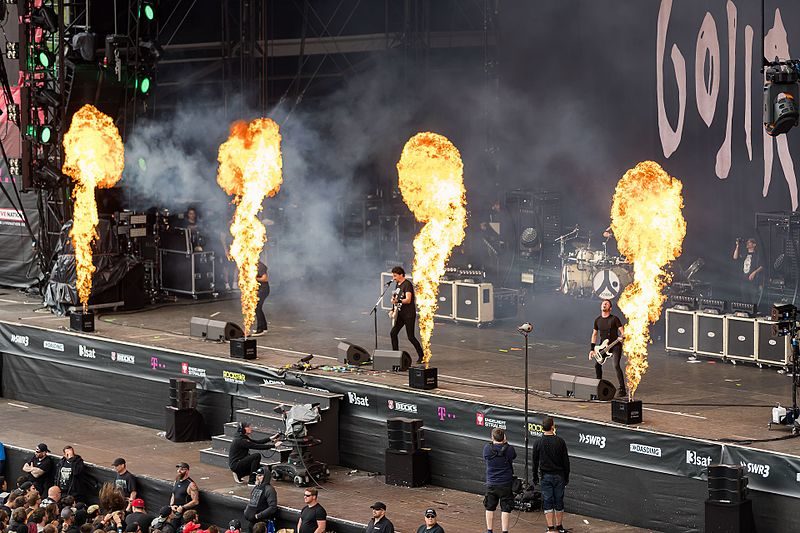

Among the most popular contemporary eco-hardcore acts is the French death metal outfit Gojira, whose members take environmentalism as seriously as they take heavy music, dedicating an entire page of their website to their activism for environmental and social causes. Their seven studio albums over the course of almost two decades are an urgent plea for the planet, as well as an admonition of those that refuse to listen. The song “Silvera,” from their 2016 album Magma, encapsulates their politics: “Dead bodies falling from the sky. / We are the ape with the vision of the killing. / A rain of shame that fills the mines. / No other blood in me but mine. / Time to open your eyes to this genocide.”

Other eco-hardcore bands have worked to promote vegetarianism and veganism within the hardcore scene. San Diego-based grindcore outfit Cattle Decapitation, whose lead singer Travis Ryan is vocal about his veganism, has made its critiques of environmental destruction clear through its grisly album covers. The band’s 2015 release, The Anthropocene Extinction, depicts a decaying human corpse lying in toxic waste with bits of synthetic plastic garbage falling from its exposed stomach and torso. The album opens with the song “Manufactured Extinct,” whose lyrics—for those that can understand them—read: “Altered climate, acceleration exacerbated by our human activities. / We used it up, we wore it out. / We made it do what we could have done without. / Machines to make machines, fabricating the end of all living things.” Such music—like its right-wing counterparts— builds communities around shared political ideas and a love of brutal tunes. Nathan Snaza, a professor at the University of Richmond and doctoral candidate Jason Netherton, a founding member of the legendary death metal bands Misery Index and Dying Fetus, discuss in their book Community at the Extremes how death metal rebels against humanist norms on which capitalism and the state are built. By embracing themes such as death and by challenging the socio-political expectations of what human bodies can and should do, this music flips the script on traditional claims to the humanistic morality of polite society. While critics may scoff at such radical artistic performances, these bands use post-humanistic perspectives to critique humanism according to its own terms. In doing so, hardcore bands produce both rebellion and escapism, creating space for what Snaza and Netherton call “more-than-human practices of community” that snub systems of oppression and destruction with satire and unrelenting sound.

In these albums, a post-human figure begins to take center stage, manifested in vocalists who are pushing the boundaries of what most people consider singing and, for that matter, language. In hardcore music, vocalists will often scream or yell instead of sing. Lyrics can be all but incomprehensible, assuming the form of guttural growls and other vocal techniques known in the hardcore scene as “pig squeals,” “dinosaur growls,” and “walrus screams.” To deliver these dissonant songs with political ideas, the human voice becomes increasingly warped, forcing listeners to fill in the blanks when the noises are beyond their ability to comprehend.

From their music to their merchandise to their activism, these bands blur the line between the human and non-human. Cattle Decapitation’s 2004 release Humanure is notable for its cover art, a vivid depiction of a cow defecating human body parts. Other visuals present ironic, absurdist human-animal inversions to highlight animal rights issues like medical experimentation and industrial animal slaughter. The cover of Earth Crises’ Forced to Kill (2009) features a monkey holding a scalpel as it peers ominously over the open brain cavity of a conscious human subject. The thrash metal band GWAR, which has stoked controversy for mutilating effigies of Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump on stage, won additional notoriety in 2012 with a graphic music video encouraging people to wear clothing made of human pubic hair—a gesture in support of PETA’s anti-fur campaign.

In seeking to overcome the boundaries between humanity and animal life, other bands have dispensed with the human voice altogether. Hatebeak and their grey parrot frontman Waldo is currently recording a split album along with Grim Squeaker, a guinea-pig fronted band. New York City-based Caninus and their pitbull terrier vocalists, Budgie and Basil, have released one solo album as well as one split album apiece with Hatebeak and Cattle Decapitation. “We met a guy who was trying to teach his African Grey parrot to use a mini-drum pad,” recalled Mark Sloan, one of Hatebeak’s founding members. “But I don’t think that went very well.” While throwing open the door to artistic experimentation, working with animals as musicians nevertheless present certain practical hurdles in regards to navigating temperament and coaxing the animals to “perform.” “[Waldo] is always a blast to work with,” says Sloan, “he can be a diva at times, but I suppose we all can.” Still, Sloan claims, “I find birds easier to work with than people, and a lot more entertaining.”

These artistic experiments are not always explicit about their politics. Evoking the tradition of feminist social theorist Donna Haraway, they are playful, collaborative, multispecies encounters meant to engage with animals on different terms while also raising non-human voices and visibility within popular culture. Far from the obedient figures of Lassie or Flipper, these animals are really, really pissed—and, considering the state of animal protections at large, they have every right to be. “Politically,” says Sloan, a self-described bird person who raises chickens in his spare time, “our only goals are to help publicize the plight of our feathered friends. We take avian equality very seriously.”

Some musicians consider eco-hardcore music as more than a forum for political expression, but as a form of spiritual transcendence. In a 2012 interview for VICE News, Russel Menzies, who performs as the black metal band Striborg, explains as he walks through a Northern Australian forest dressed in a black robe: “I am just a carrier, I am just a medium for doing this. The instruments are mimicking the elements and essence of nature, for sure. My guitar would be the mist, the frost, the snow, the winter. Drums would be like the heart of the land. The trees and the rocks and certain things like that, the vocals would be like the voice of the forest.” For Menzies and his peers, this music approaches a kind of religious belief system that draws heavily on paganism, eco-feminism, and Satanism. These ideas are not only a framework for their music, but also for radical lifestyles and ceremonial practices.

One of hardcore’s heavier genres, black metal is known for its walls of thrashing guitar, blasting drums, and tormented vocals with themes and imagery that are often fixated on the non-human world. On black metal, Menzies has said, “[t]his kind of music, this kind of belief system, has got very little to do with being a human being and showing yourself as a human being.” The use of corpse paint is a common practice in black metal and involves covering the body with paint to resemble a dead corpse. Jef Whitehead, of the band Leviathan, explains that the black hollow eyes and pale white skin of the corpse paint is a way of removing the human factor from his music; the music “was formed by itself,” he says, the hands of its human creator obscured to the point of oblivion. The result is a clawing attempt to express what the non-human cannot, and to establish a connection, however dystopic and foreboding, with the non-human world.

Sascha Pöhlmann, a professor of American literary history at the Ludwig-Maximilian University in Munich, draws parallels between black metal and the writings of American Romanticists such as Walt Whitman. Both of these art forms, he argues, pose a post-human vision of future earth that foregrounds ecological issues along with spiritual transcendence. Bands such as Wolves in the Throne Room, Agalloch, Eldamar, and Lascar represent a thriving community of musicians and artists intent not only on giving a voice to the non-human, but also transcending the narrow confines and perspectives of the human condition. According to Aaron Weaver, lead singer of the legendary black metal crew Wolves in the Throne Room, this music functions as a “psychiatrist for the world,” overcoming the alienation of the modern society and producing instead a spiritual, life-affirming re-connection with ourselves and our planet.

As an avid fan of heavy music, I was first drawn to the eco-hardcore genre while working on environmental issues in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. In the context of a degrading global ecosystem, terrible socio-economic inequality and rapid climatic change, the slow plod of environmental and humanitarian research and activism seemed to me a disheartening, bureaucratized struggle. Eco-hardcore music represented an outlet for these experiences and frustrations. Over time, the political messages in this music helped me to marshal the resolve to do my work and to articulate some of my own political ideas and positions. Eco-hardcore music is so politically powerful in part because it is so provocative, lending itself to the aims of the environmental and post-humanist movements in more ways than one.

Hardcore music can be a platform for unprogressive ideas. The scene, while at times diverse and inclusive, still tends to be predominantly white and male and prone to violence. Further, many of the same critiques of post-humanism can be leveled at the eco-hardcore musical movement. Many marginalized and minority groups have pushed back, asking: how can we embrace post-humanism when some of us have never been considered fully human, accorded due rights and privileges, in the first place? Post-humanism in hardcore music is often accompanied by a hefty dose of misanthropy, fellow Homo sapiens be damned.

Yet eco-hardcore, more explicitly than any other musical genre, is grappling head-on with the absurd and apocalyptic realities of the Anthropocene. As this generation attempts to rewrite the stagnant politics and hollow institutions that have come to define the neoliberal and post-modern era, eco-hardcore music is providing a powerful and unrepentant form of expression. Through its performers’ activism as well as the discourses it produces around social change and environmental stewardship, eco-hardcore is both an artistic refuge and a source of energy for political movements. It might also represent a home in which to rest, a final sanctuary from which to scream hell and fury into the void as humankind claws precipitously towards a doom of its own making. What could be more metal than that?